“I’m in prison and I don’t why – going to be tried and I don’t know why. It’s very personal for me. A very personal expression…it’s the most autobiographical movie that I’ve ever made”

– Orson Welles on making The Trial

Spring 1962: Orson Welles is in Yugoslavia filming The Trial. He’s heard the film is running out of cash and is about to be cancelled. The state authorities have also heard this. They plan to confiscate any expensive film equipment they can get their hands on. Welles has run-up an excess of debts and now someone will have to pay.

One dark cold night, executive producer Michael Salkind calls Welles and says he’s shutting the film down, capeesh? Welles doesn’t even blink. He tells Salkind pay the hotel bill and book us a train ticket out of town. An hour later, Welles and co. skip town en route to Paris.

Michael and his son Alexander Salkind worked with Welles once before. It was on a movie called The Battle of Austerlitz in 1960. Pleased with the outcome, the Salkinds approached Welles and offered to finance any movie so long as it was based on a work of fiction. One in the public domain. Welles hummed and hawed. He eventually opted for Franz Kafka’s The Trial.

As Welles told Peter Bogdanovich he was attracted to Kafka’s novel as he “had recurring nightmares of guilt” and of being put on trial throughout his life:

I’m in prison and I don’t why – going to be tried and I don’t know why. It’s very personal for me. A very personal expression…it’s the most autobiographical movie that I’ve ever made, the only real one that’s really close to me…It’s much closer to my own feelings about everything than any other picture I’ve ever made.

Chapter One Arrest – Conversation with Mrs. Grubach – Then Miss Bürstner

Someone must have been telling lies about Josef K., he knew he had done nothing wrong but, one morning, he was arrested. Every day at eight in the morning he was brought his breakfast by Mrs. Grubach’s cook – Mrs. Grubach was his landlady – but today she didn’t come. That had never happened before. K. waited a little while, looked from his pillow at the old woman who lived opposite and who was watching him with an inquisitiveness quite unusual for her, and finally, both hungry and disconcerted, rang the bell. There was immediately a knock at the door and a man entered. He had never seen the man in this house before.

He was slim but firmly built, his clothes were black and close-fitting, with many folds and pockets, buckles and buttons and a belt, all of which gave the impression of being very practical but without making it very clear what they were actually for. “Who are you?” asked K., sitting half upright in his bed. The man, however, ignored the question as if his arrival simply had to be accepted, and merely replied, “You rang?” “Anna should have brought me my breakfast,” said K. He tried to work out who the man actually was, first in silence, just through observation and by thinking about it, but the man didn’t stay still to be looked at for very long. Instead he went over to the door, opened it slightly, and said to someone who was clearly standing immediately behind it, “He wants Anna to bring him his breakfast.”

There was a little laughter in the neighbouring room, it was not clear from the sound of it whether there were several people laughing. The strange man could not have learned anything from it that he hadn’t known already, but now he said to K., as if making his report “It is not possible.” “It would be the first time that’s happened,” said K., as he jumped out of bed and quickly pulled on his trousers. “I want to see who that is in the next room, and why it is that Mrs. Grubach has let me be disturbed in this way.” It immediately occurred to him that he needn’t have said this out loud, and that he must to some extent have acknowledged their authority by doing so, but that didn’t seem important to him at the time.

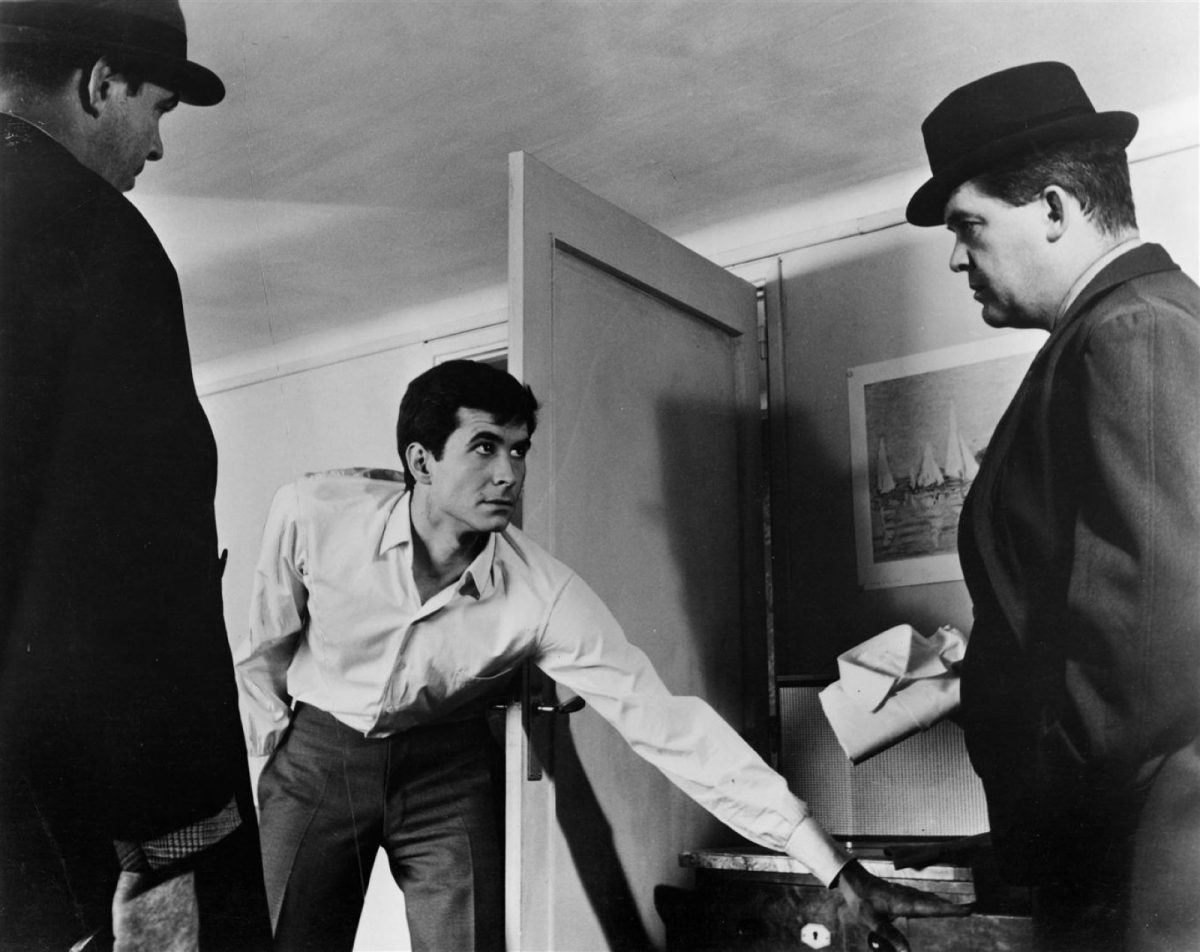

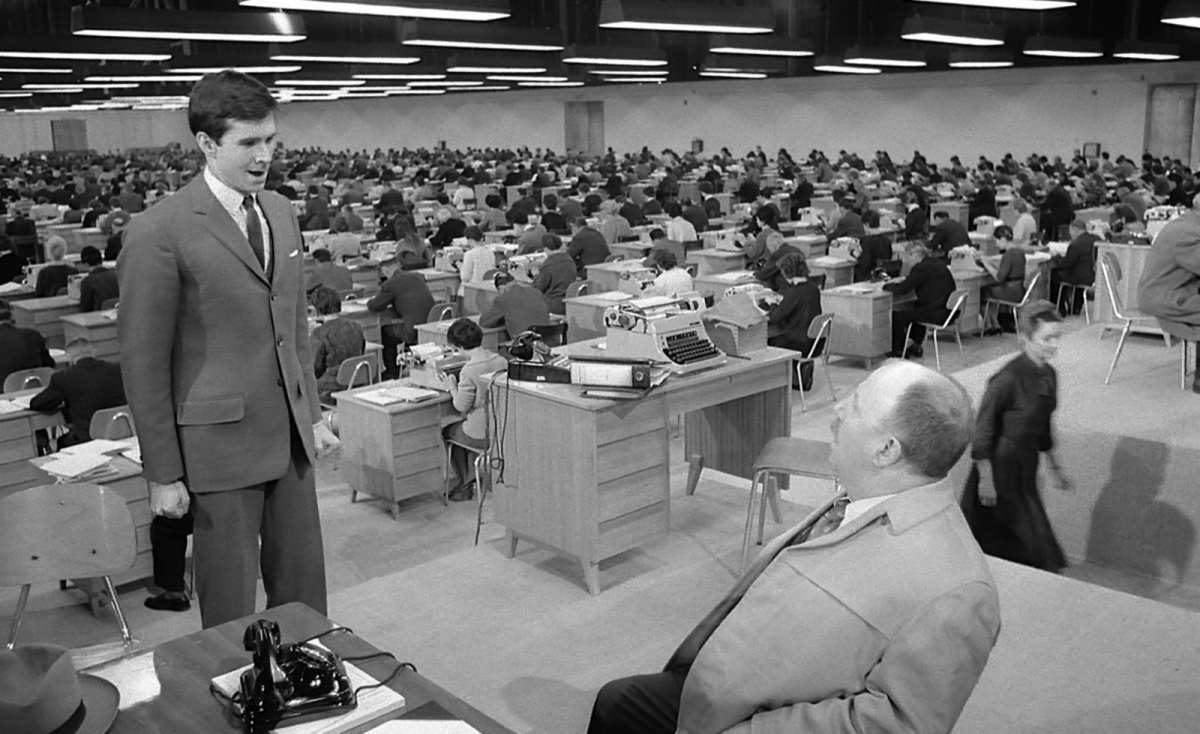

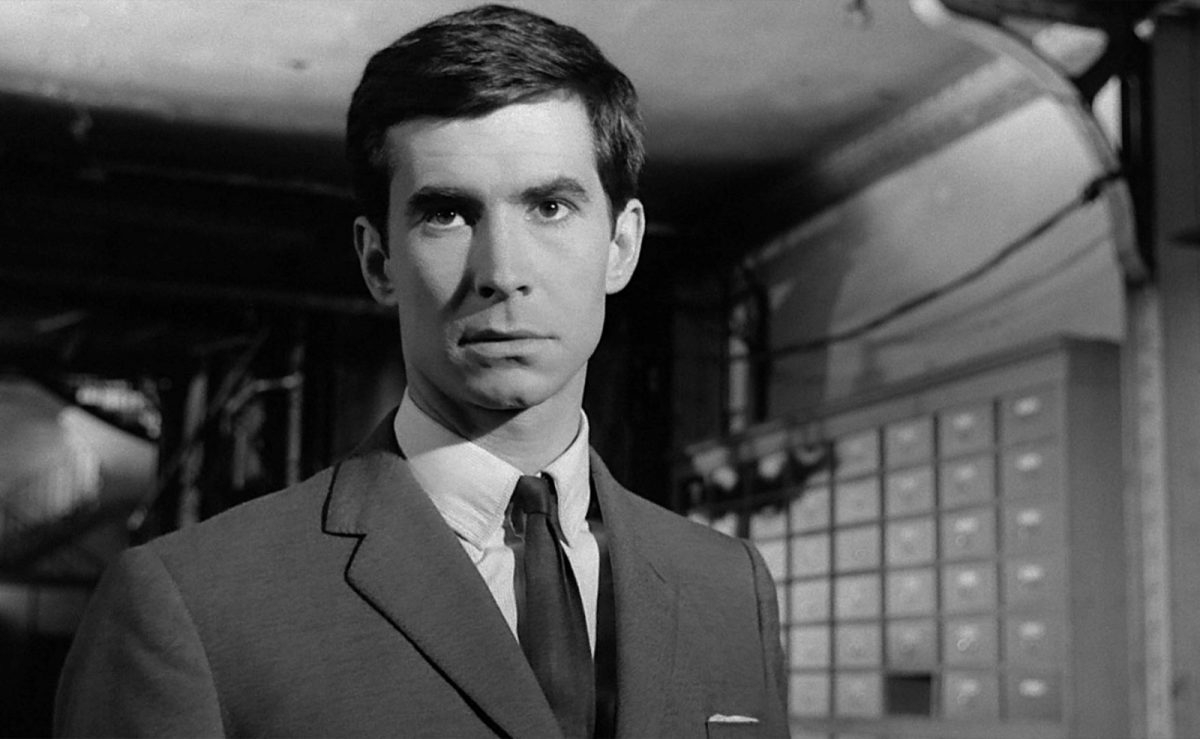

Welles wanted comedian Jackie Gleason to star as Kafka’s hero Josef K. But Gleason didn’t want to fly (according to Welles) or was too busy (according to Gleason). Welles opted for Anthony Perkins, who had impressed in Psycho.

Perkins’ Josef K. mixed an excess of nervous energy with the needy ambitions of a petit bourgeois clerk.

Franz Kafka was 31 when he started writing The Trial in the summer of 1914. He had split from his girlfriend, which according to the writer and Nobel Laureate Elias Canetti was the inspiration for The Trial. It certainly played a part. As his friend and biographer Max Brod noted: Kafka “always found fault with himself” and reproached “himself with coldness, incapacity for life, lifelessness…” He heightened these perceived failings to create characters like Josef K. who:

…had not married, remained a bachelor, had allowed himself to be terrified by the reality of life, but had not defended himself against it–that is his secret guilt, which had already, before his condemnation, shut him out from the circle of life.

But let’s not be too hasty to portray Kafka as some neurotic emo unable to function in life. He had as Brod stated “the streak of joy in the world and in life.”

When Kafka read aloud himself, this humour became particularly clear. Thus, for example, we friends of his laughed quite immoderately when he first let us hear the first chapter of The Trial. And he himself laughed so much that there were moments when he couldn’t read any further. Astonishing enough, when you think of the fearful earnestness of this chapter. But that is how it was.

Welles movie missed this dark, uncanny humour. He described his film as “a dream–a particular nightmare–inspired by Kafka. It’s surrealist, if you want. But the good surrealists aren’t symbolists.”

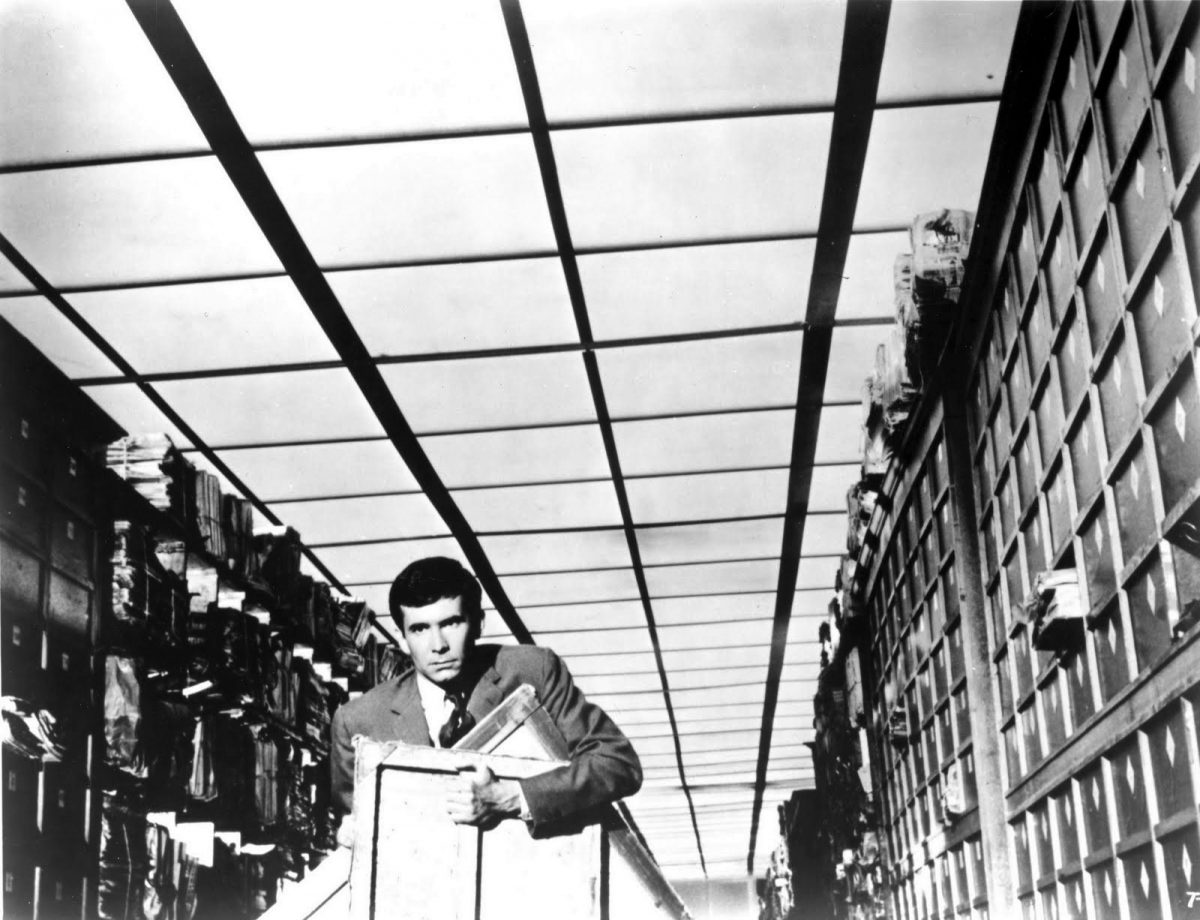

Welles finished his filming in Paris, using the abandoned Gare d’Orsay as his film set. On its release, The Trial divided critics. Some thought there was no heart in the film, no emotional resonance to connect with an audience. It was a movie to be admired, complimented on its craft, technique, style, and vision.

However, many others agreed with Welles who considered it his best film as it was his:

…own picture, unspoiled in the cutting or in anything else. That’s why I hate to hear it is not as good, because I can’t blame anybody for it [laughs].

Max Brod wrote Josef K. was “dead” or rather “lifeless matter” from the beginning of the book as K. failed to engage proactively in life. Instead, he awaited a response from God to confirm his existence. His crime or guilt came through his failure to take responsibility for his own actions. Therefore, he was guilty from the moment he was arrested.

Welles also thought K. guilty because he allowed himself to live in a world that oppressed liberty. Which is perhaps a lesson for us all.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.