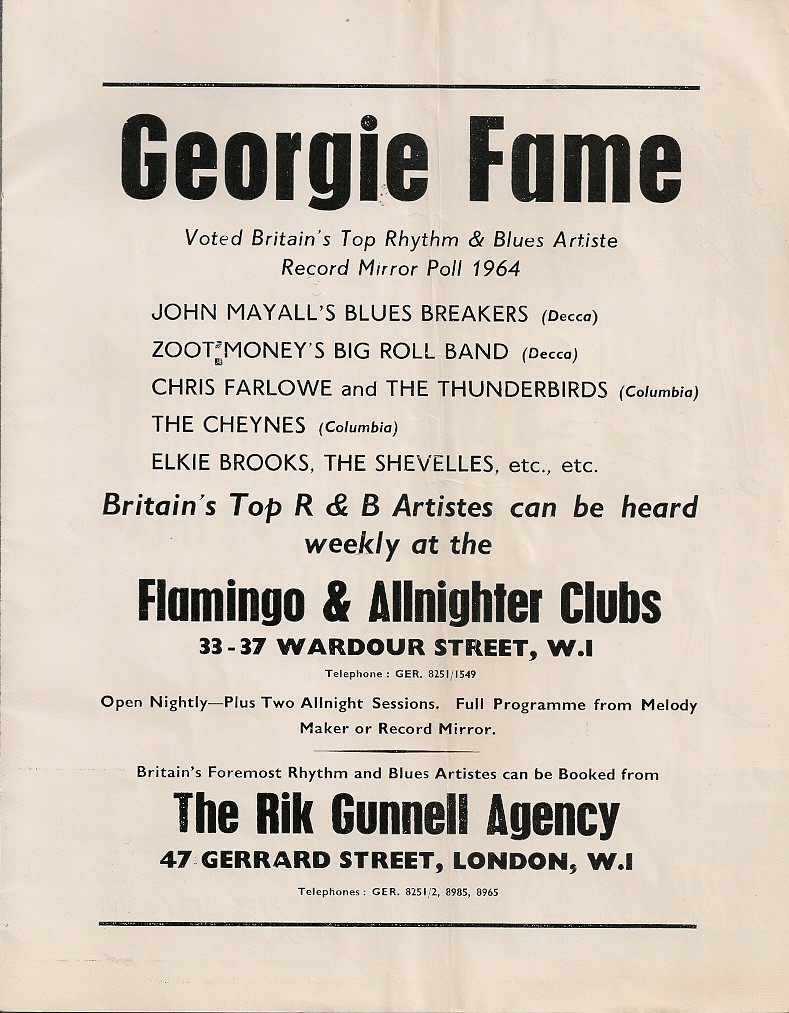

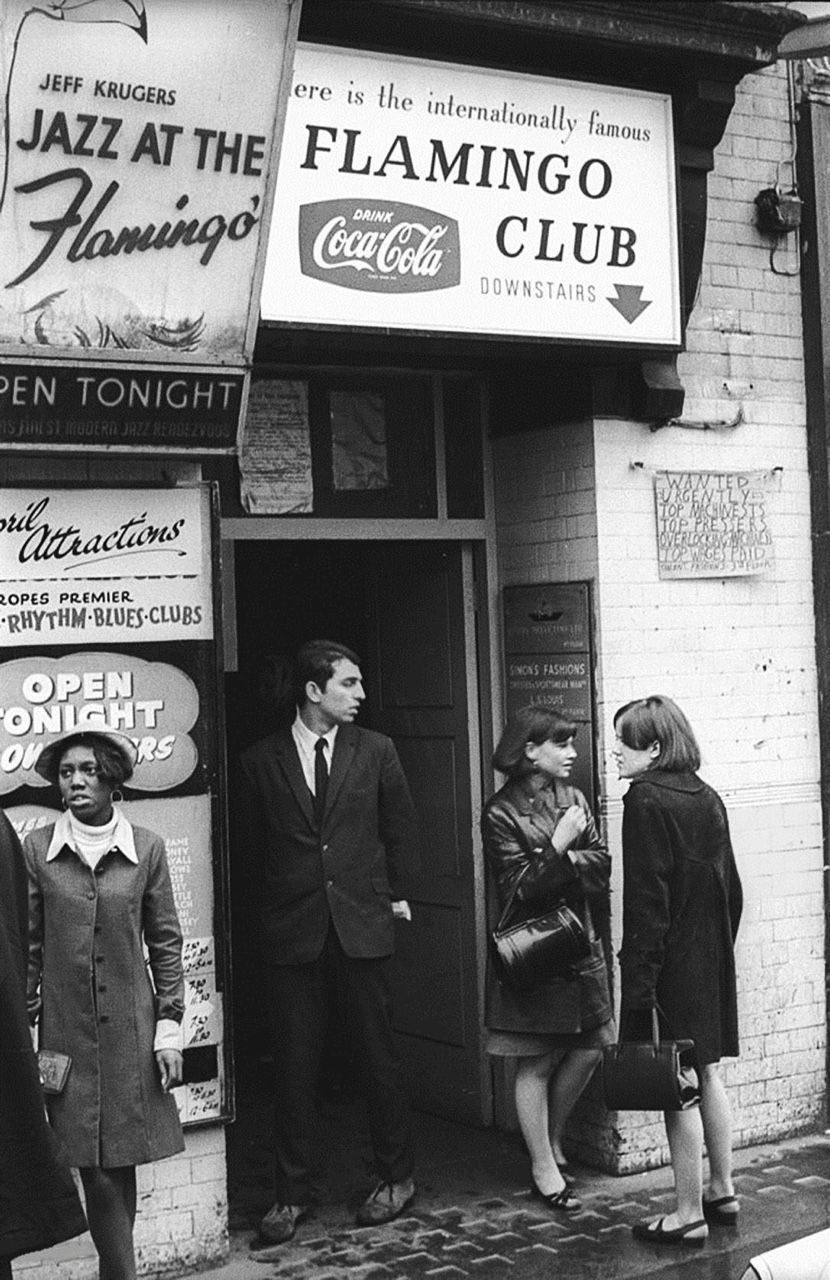

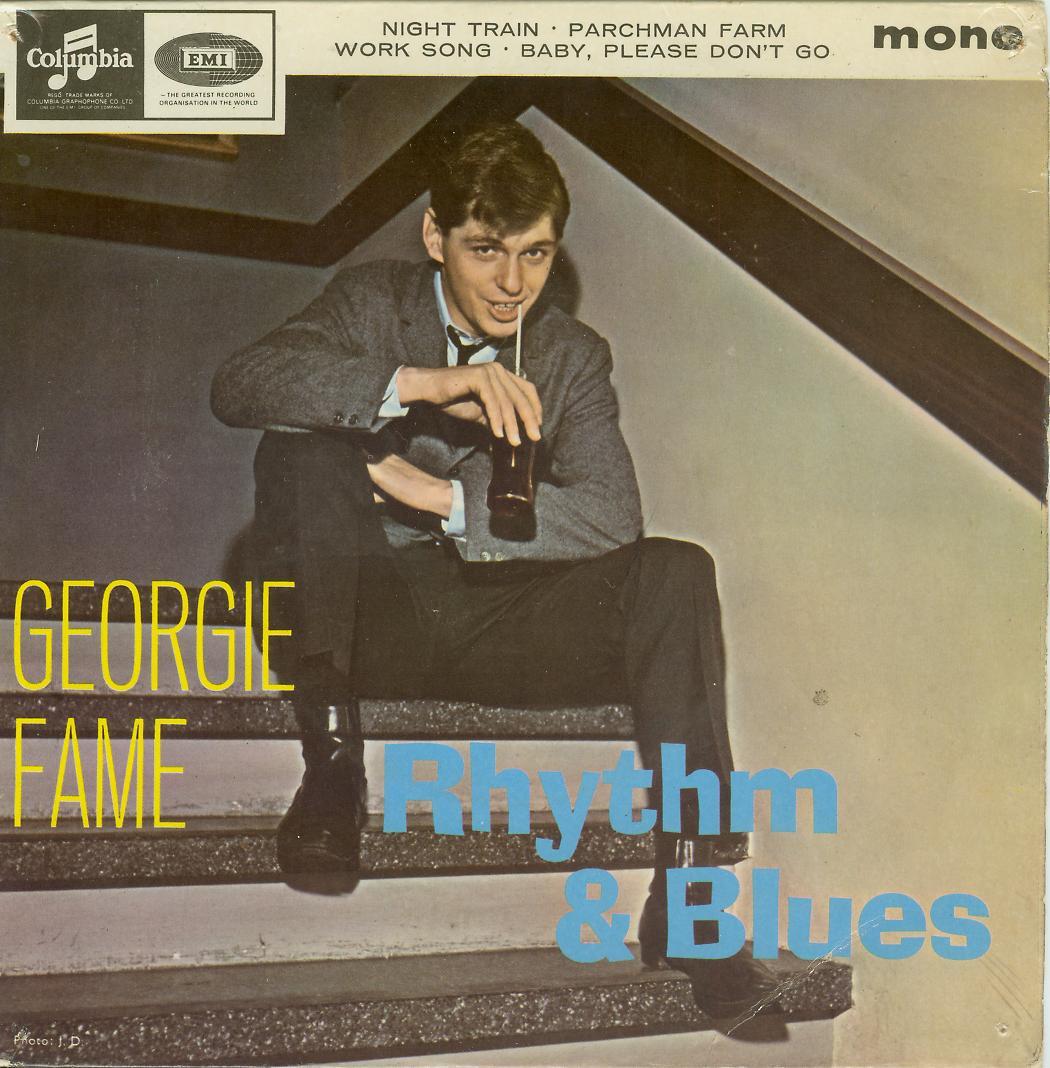

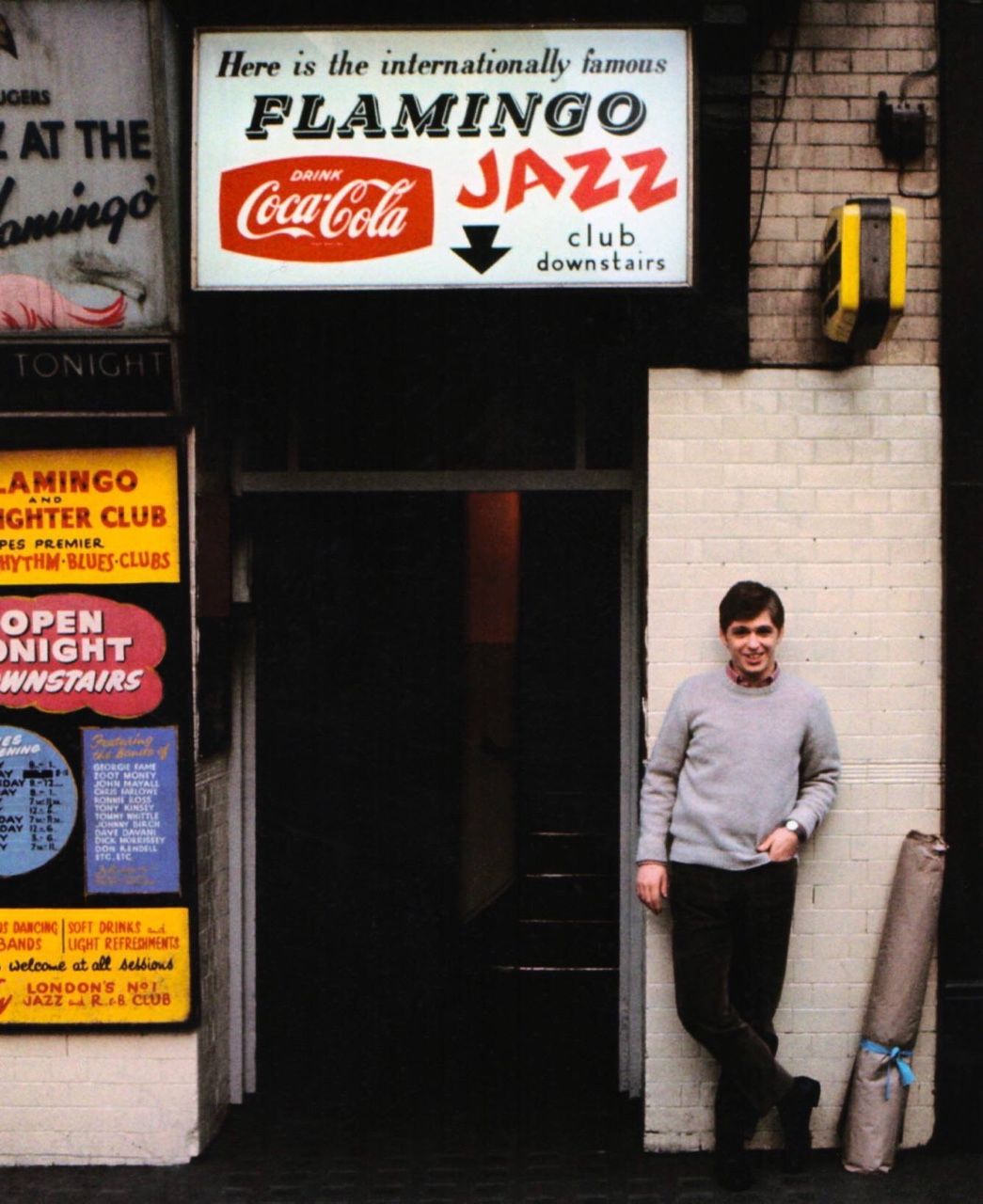

In March 1962, a month after Billy Fury had dismissed them as his backing band – he felt they were ‘too jazzy’ – Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames started a three-year residency at The Flamingo Club. It was a sweaty, smoky, scarlet-walled nightclub in the basement at 33-37 Wardour Street, opposite Chinatown’s Gerrard Street and it was famous for its weekend all-nighters when it stayed open from midnight until six in the morning.

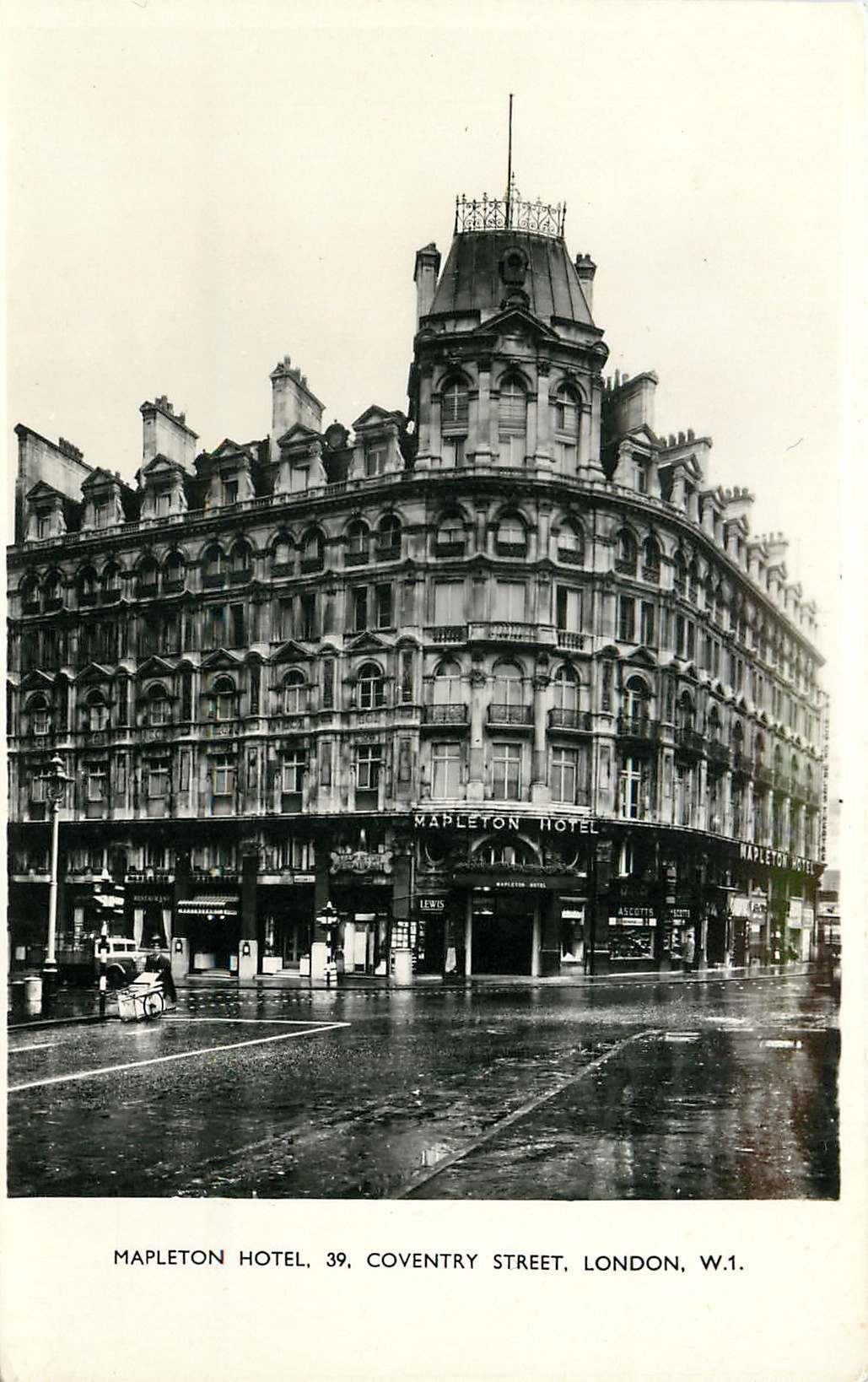

The Flamingo Club had only been based at the Wardour Street premises for four or five years and had actually started ten years previously just down the road next to Leicester Square. A 21-year-old film salesman and occasional ’30 shillings a night’ pianist called Jeffrey Kruger had dinner at the Mapleton Hotel on Coventry Street. A big jazz fan, Kruger often wondered why every jazz club he visited was always such a dive. He would later say: ‘The biggest hold-up to jazz in this country was that it got a bad name. It was associated with dirty cellars, drink and people who had no respect for themselves.

After talking to Tony Harris, the manager of the hundred-roomed hotel, Kruger was shown a basement which he saw would be perfect for his idea of a new kind of jazz club. ‘‘Jazz at the Mapleton’ opened in August 1952, and people came to hear modernist jazz from musicians such as Ronnie Scott, the Johnny Dankworth Seven, and Kenny Graham’s Afro-Cubists. After a few months the club changed its name in honour of Kenny Graham’s composition ‘Flamingo’, and the newly named ‘modernist’ Flamingo Jazz club took off.

Michael Burke, who was fifteen in 1954, spoke of his time at the Flamingo to Rob Baker in his book ‘Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics’, describing the basement club:

“It was down a few stairs; (I think it was about 3/6 to get in), into a fairly large, quite well-lit room … . No alcohol was sold, only soft drinks; Coca Cola, stuff like that. The small dance floor was to the left of many rows of chairs facing a raised stage. To the right was another area containing toilets, the drinks counter, and a dressing room for the musicians. Many of the young men wore what was the fashion of the time, charcoal grey draped suits, “Mr. B” (Billy Eckstine) white shirts with roll collars, and skinny “slim-Jim” ties.”

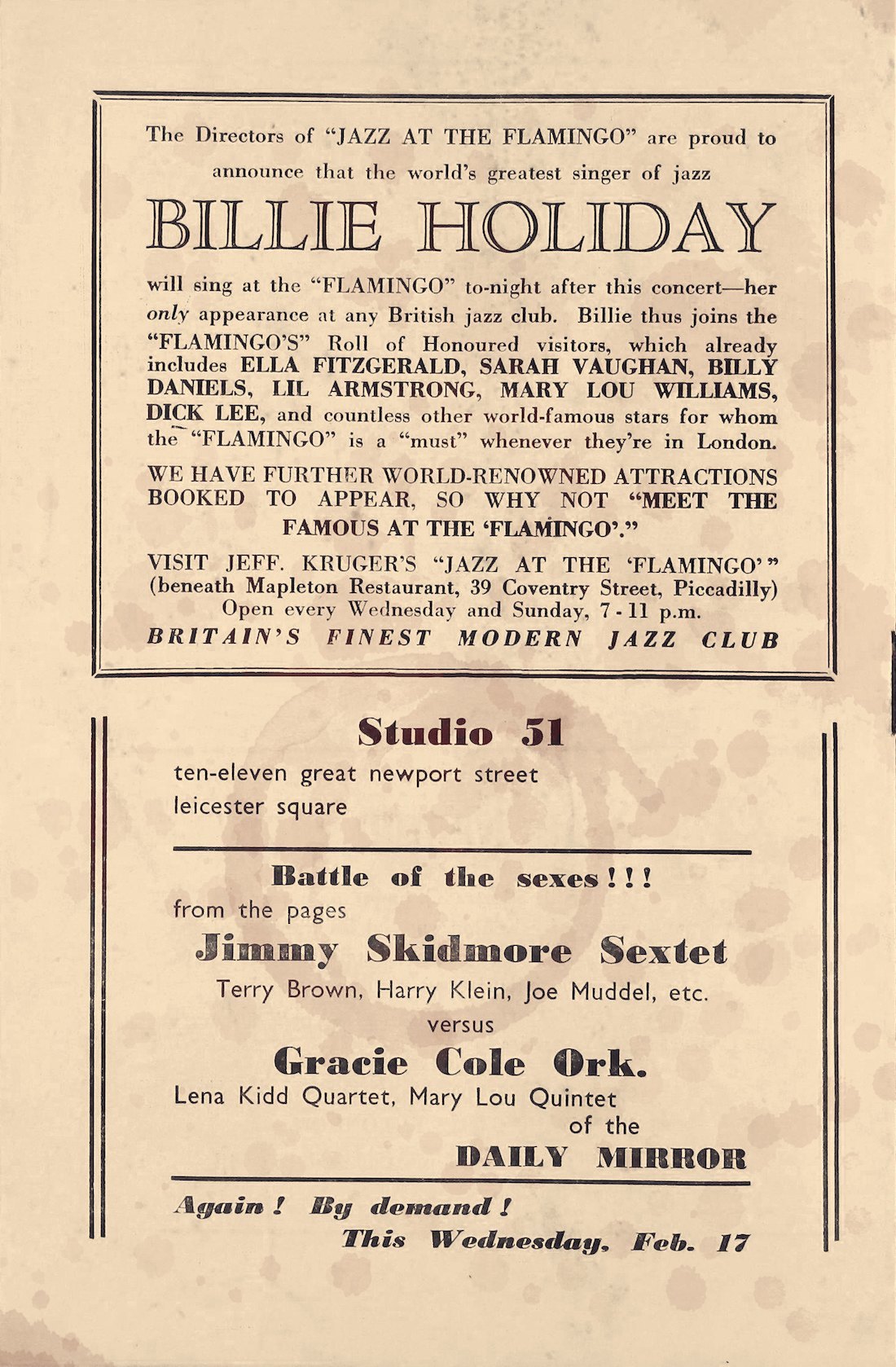

Kruger was constantly battling with the musicians’ union and when he brought over the jazz musician Chet Baker, the American was told that he could sing but not play the trumpet. If he did both he and Kruger risked jail.

The only Americans who had permits to perform were singers and in February 1954 Billie Holiday was somehow persuaded to do a gig at the Flamingo after her concert at the Royal Albert Hall. Burke remembers the night:

She didn’t actually appear at the Flamingo until about 11 pm. I got there early as usual, to ensure a seat, and by the time she arrived the room was filled to capacity. The excitement was great … you could feel the tension in the air. During the wait several well-known entertainers, including singer Marian Ryan, and a gentleman called Cab Kaye who had two black girls who sang a very great version of ‘Shine.’

Billie finally took the stage. She was still wearing the gold full-length dress she wore for her concert appearance. Her hair was black, but had gold highlights on the top. Several musicians took the stage, including a couple of sax players; I think probably Ronnie Scott and a young alto player, Johnny Rogers. Billie sang ‘Willow Weep for Me’ and ‘Lover Man’ with just piano, bass and drums, and then she said ‘how about some horns?’ but it seemed that the sax players were so bemused by her and intimidated, that they remained sitting at her feet and wouldn’t get up to blow. She continued to sing numbers for about an hour before she left the stage to great applause. The crowd left, mostly to catch the last trains and buses home.

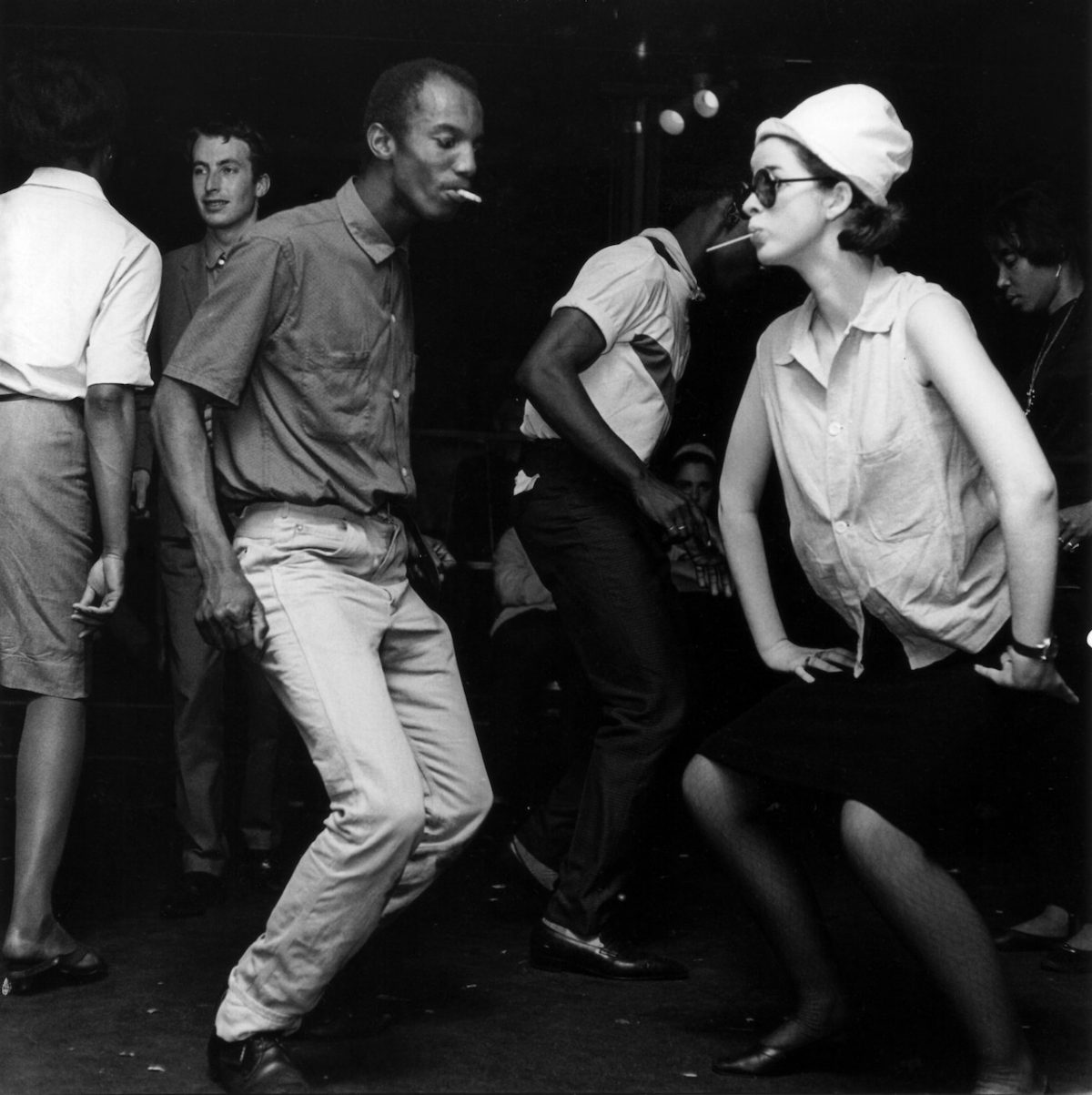

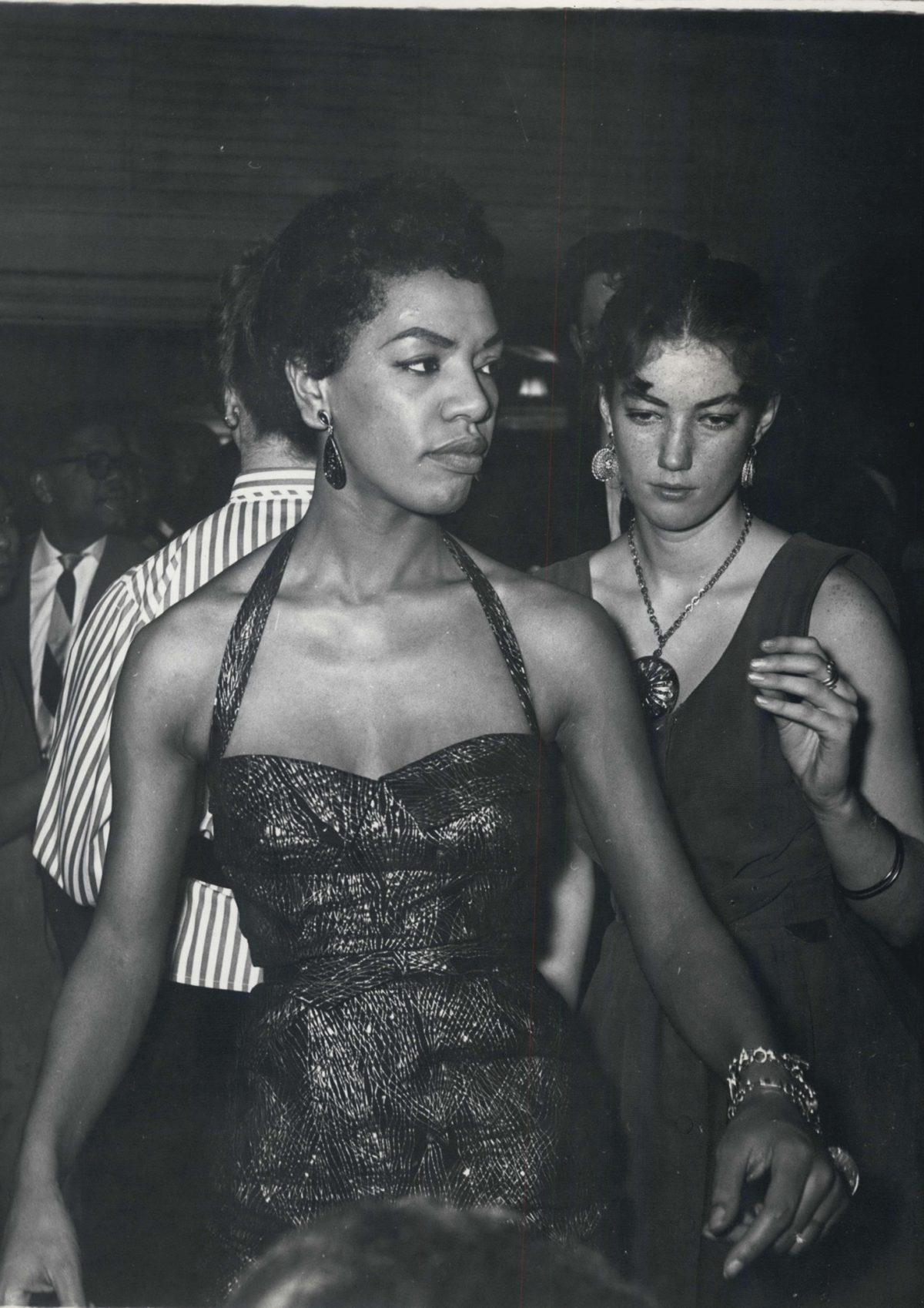

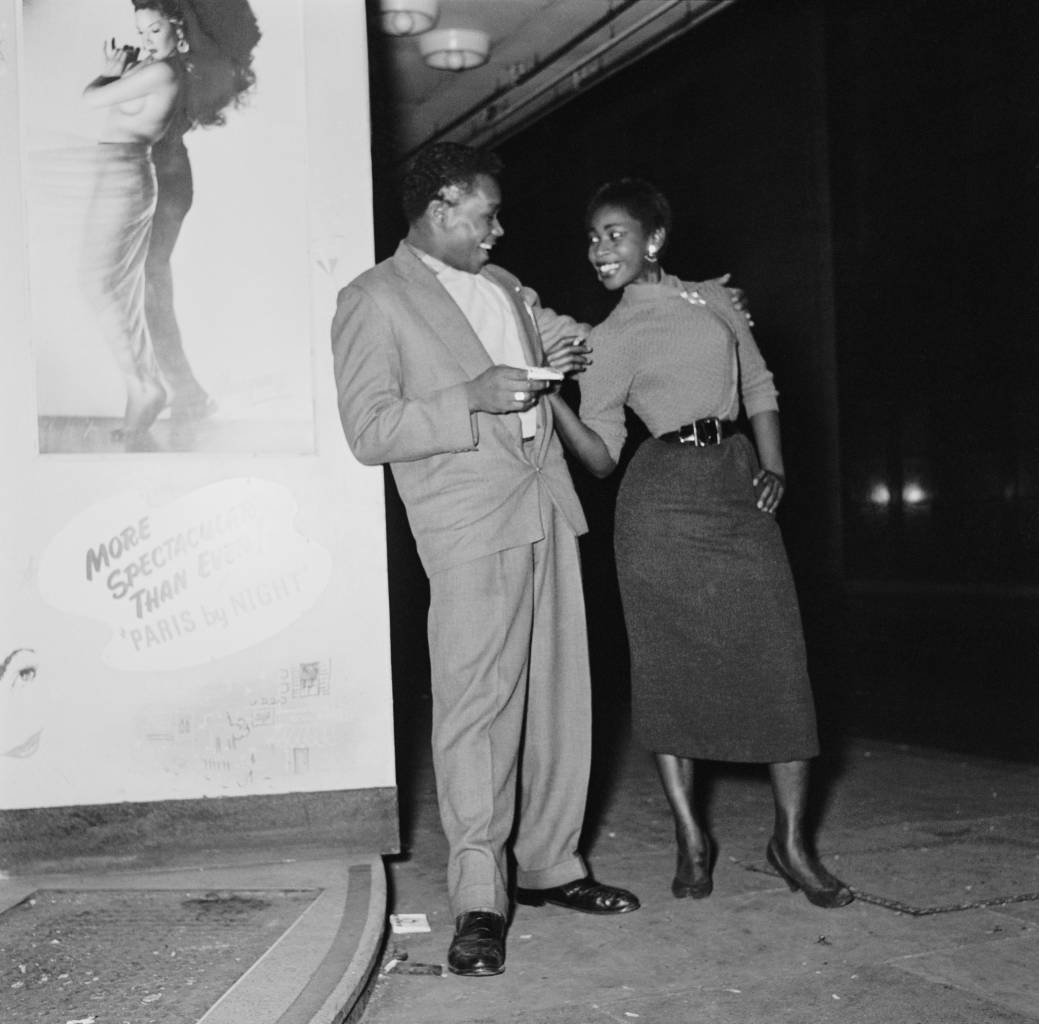

Jan 1, 1960 – American Club Dancer: One of the members who spend hours in the crowded dance floor of the Americana Club.

Club Americana

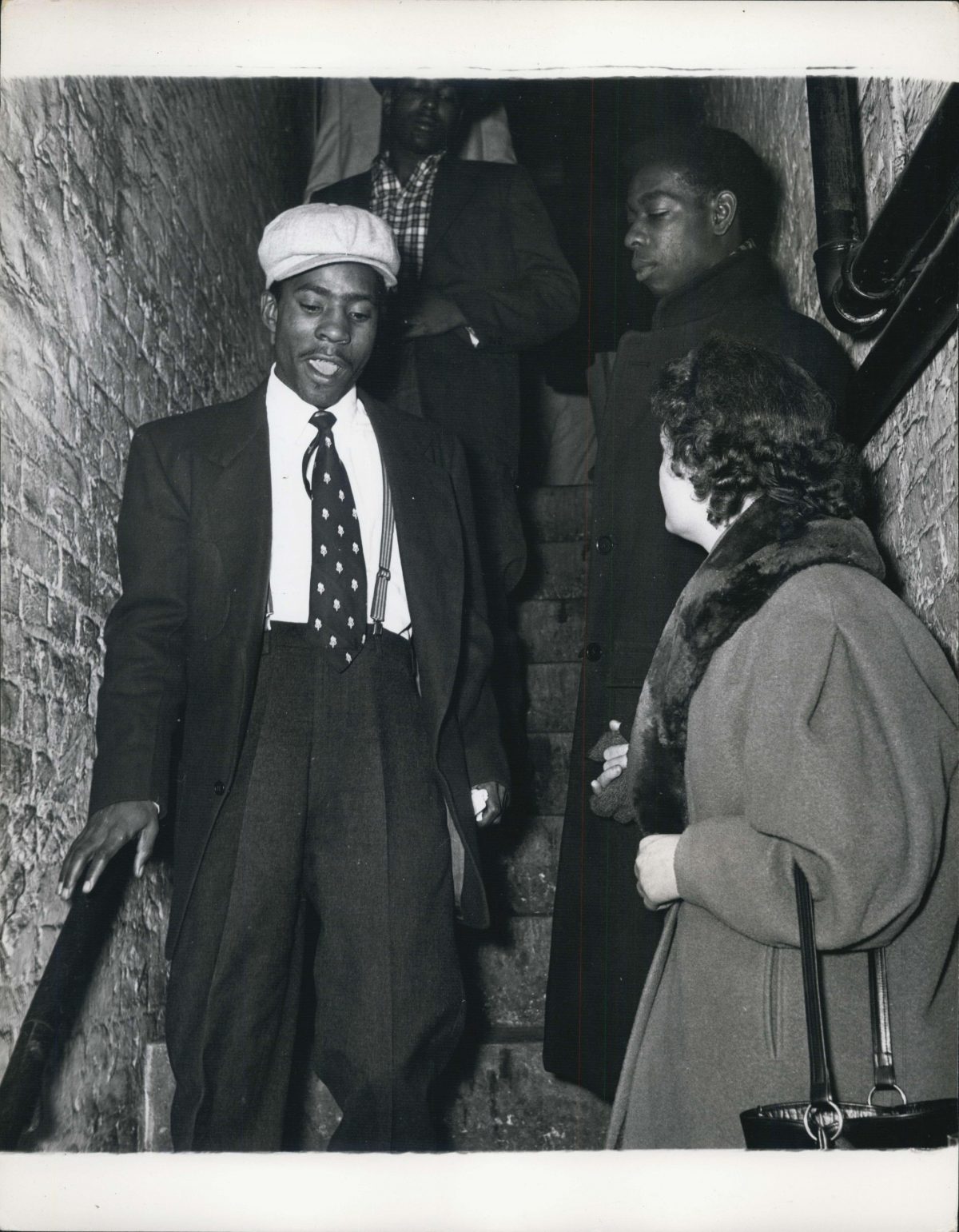

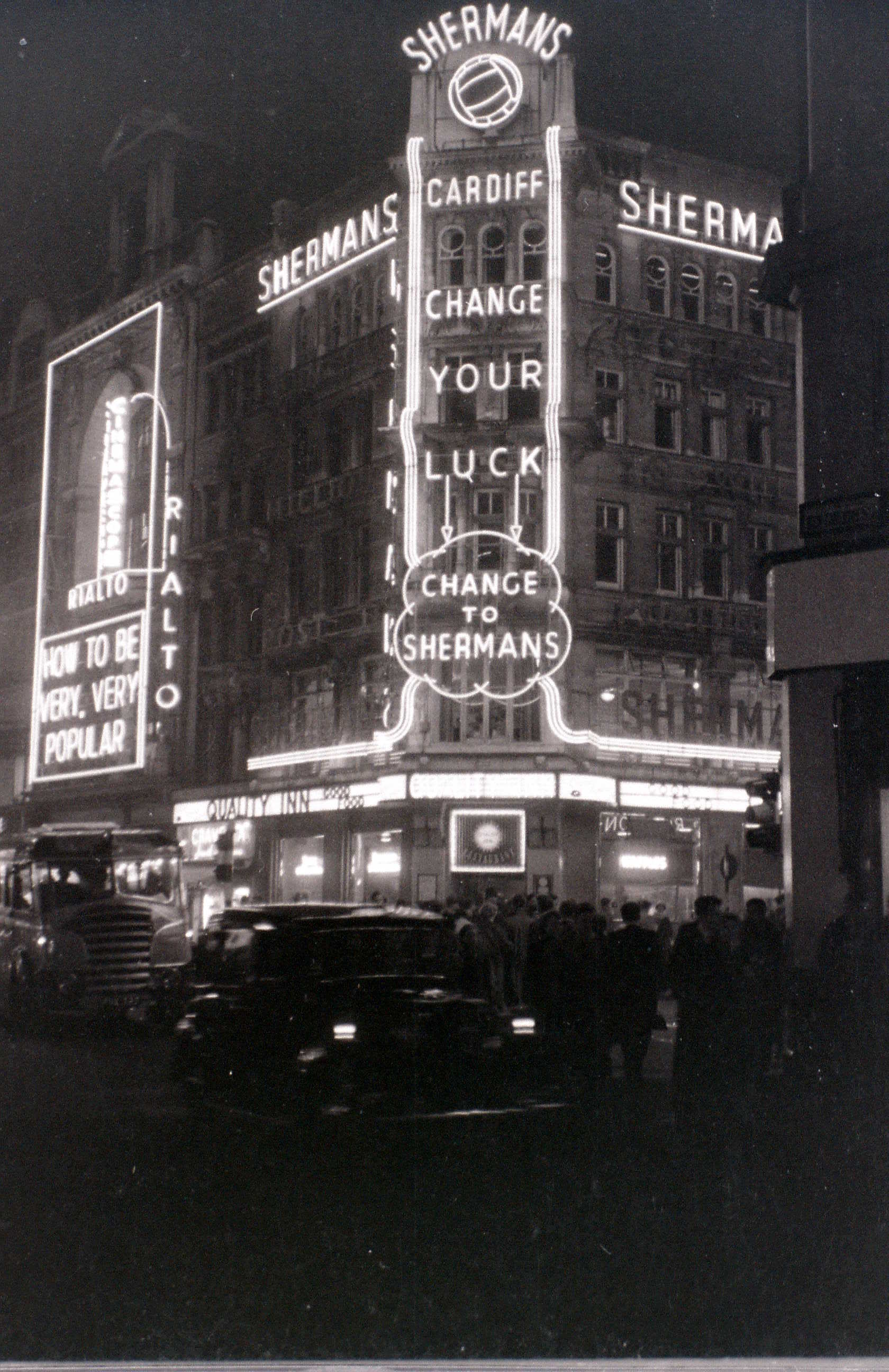

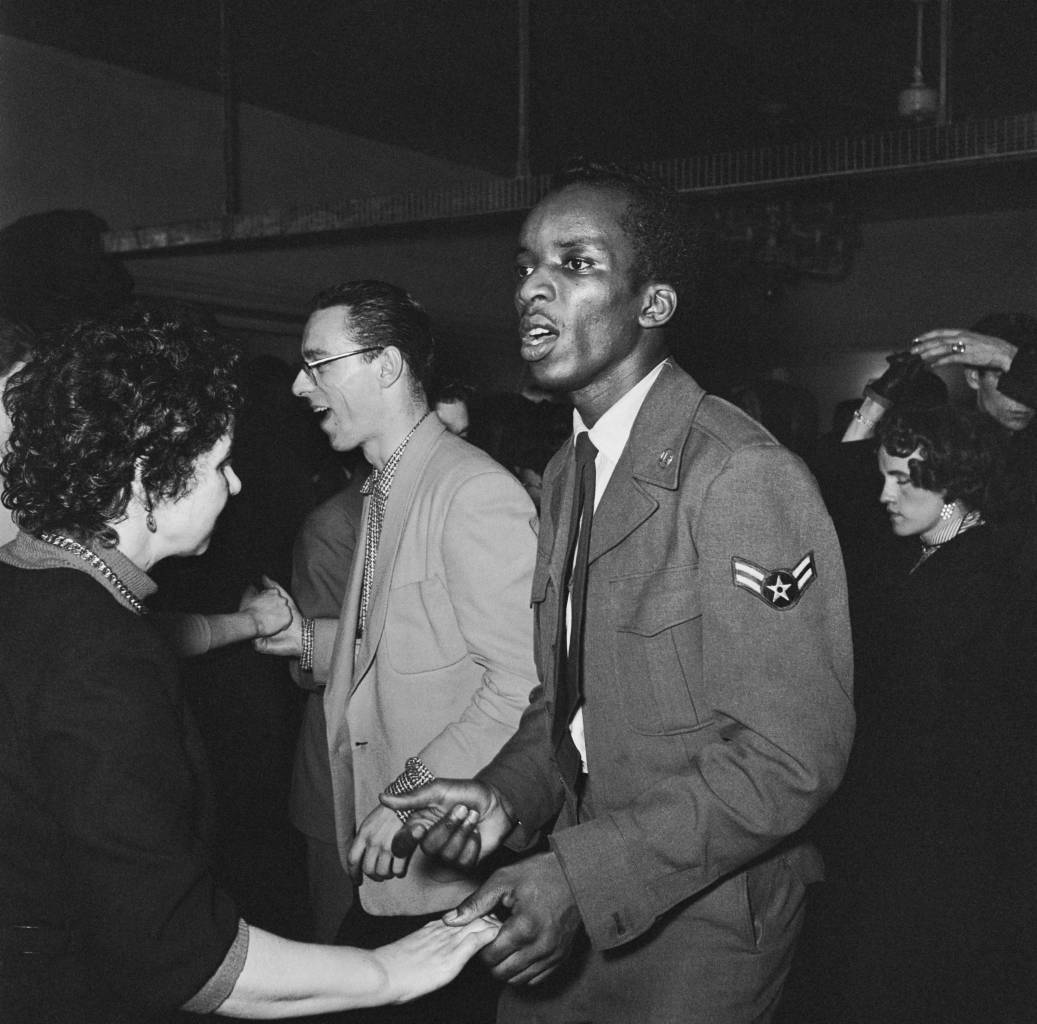

There was, however, another club night in the basement at the Mapleton (the building is still a hotel but now called the Thistle Piccadilly). It was an all-nighter that began in 1955, and took advantage of a time when American fashion was all the rage and thus called Club Americana. For ten shillings you got live jazz and a three-course meal – tomato soup, chicken ’n’ chips and ice cream. The night club was run by Rik and Johnny Gunnell and attracted black American servicemen who, only a decade after the end of the Second World War, were based in Britain in large numbers. The club was also frequented by members of the growing West Indian community.

It’s worth being reminded that clubs with a mixed crowd, outside Soho, weren’t at all common. The ‘colour bar’ was still legal and enforced at many British dance halls. Mecca’s Locarno Ballroom in Bradford refused admission to a black man in November 1961. After the Musicians’ Union told its members not to play there until the situation changed, Mecca executive, and originator of Miss World, Eric Morley responded by saying, ‘Why doesn’t the MU mind its own business?’ [10] The MU’s position on the ‘colour bar’ can be applauded, but their arcane rules about American musicians performing in Britain were still being enforced.

The scene on the dance floor at the ‘Club Americana’, a Saturday night jazz club open from midnight until 7 a.m., London, 25th November 1955. (Photo by Keystone Features/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In 1958, Club Americana soon followed the Flamingo Club and moved to premises on Wardour Street (now an Irish theme pub and a branch of Ladbrokes) and the Gunnell brothers launched the Friday and Saturday All-Nighter, but after the pre-midnight Flamingo Jazz Club had closed.

In 1963, there was a fight between two West Indian men, Johnny Edgecombe and ‘Lucky’ Gordon, who were both at one time or other a lover of Christine Keeler. The well-publicised knife-fight could be said to have kick-started the Profumo Affair. American service men were soon banned from visiting the club and drawn by the weekend all-nighters and the music policy of black American R ʼn’ B, Soul, and jazz, The Flamingo Club was already the favourite hang-out for London’s newest teenager cult, the Mods. But that’s a different story…

Couples take a break from dancing at the ‘Club Americana’, a Saturday night jazz club open from midnight until 7 a.m., London, 25th November 1955. (Photo by Keystone Features/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

A young couple pose outside the ‘Club Americana’, a Saturday night jazz club open from midnight until 7 a.m., London, 25th November 1955. (Photo by Keystone Features/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

It surprised a lot of people that Jeff Kruger had got permission from the Chief Constable at the Savile Row police station to run the all-nighter. Kruger explained: ‘I told him, if you let me have an all night licence, all the kids who hang around Soho in the early hours will go there and you’ll know where they are. You can put any number of plain-clothes men inside the club, but you’ve got to promise only to arrest people outside, never inside. There’ll be no alcohol, and we’ll stay open till the tube starts running so the kids can get home again.’

After leaving the ‘Club Americana’, a Saturday night jazz club open from midnight until 7 a.m., American troops and their girlfriends wait at Piccadilly Circus Station for the first train home, London, 25th November 1955. (Photo by Keystone Features/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

After leaving the ‘Club Americana’, a Saturday night jazz club open from midnight until 7 a.m., American troops and their girlfriends say goodbye in Piccadilly Circus, London, 25th November 1955. (Photo by Keystone Features/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

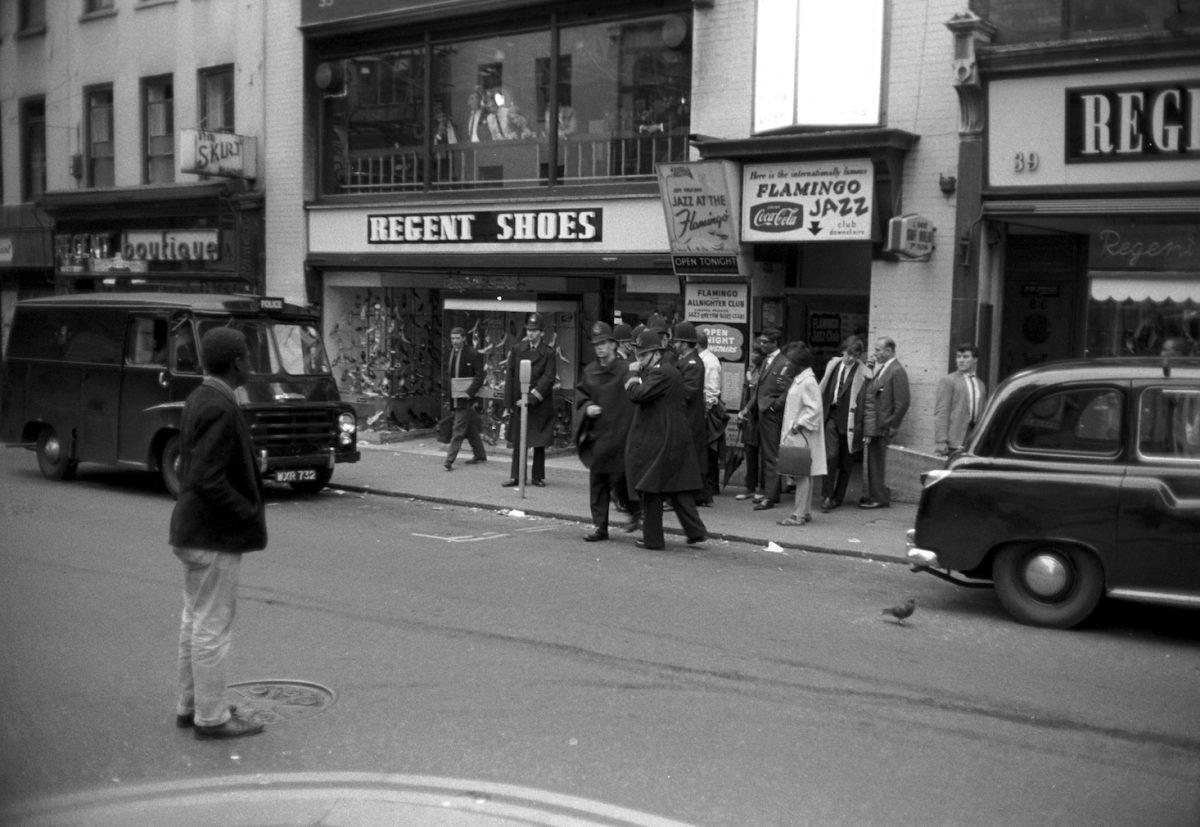

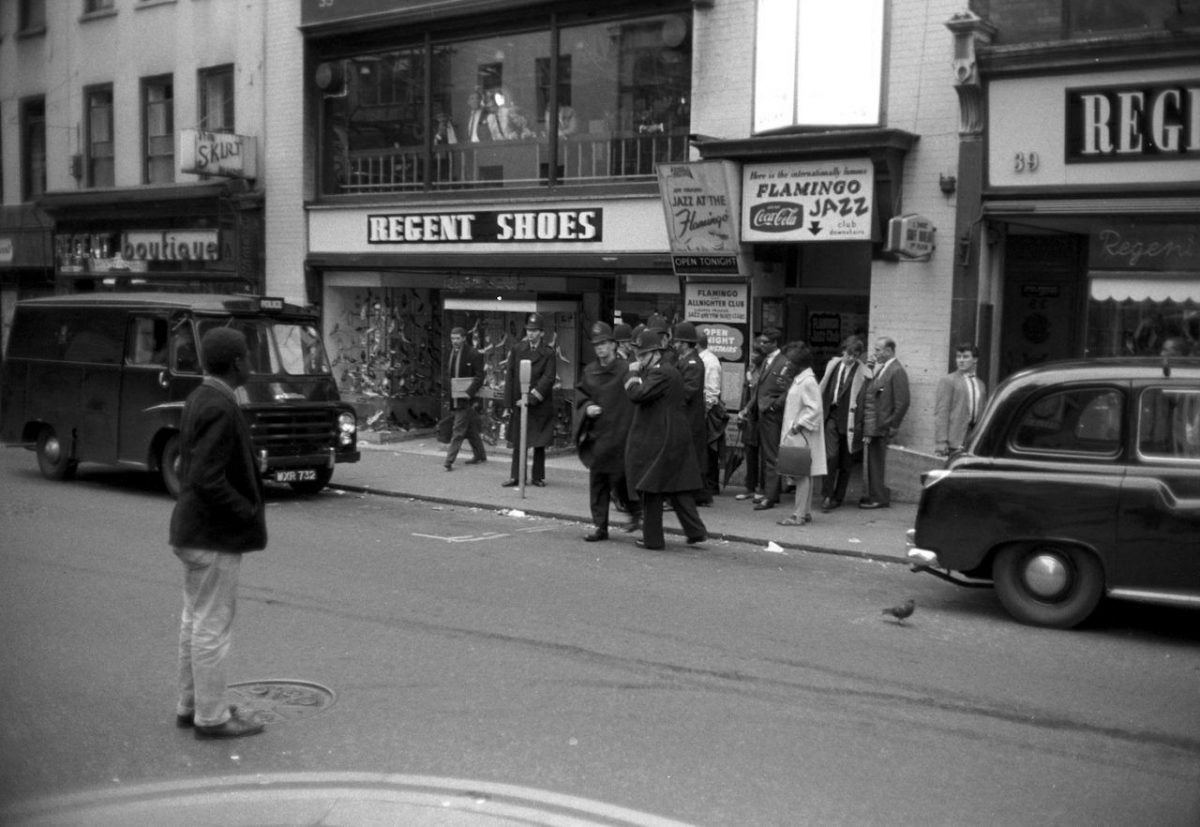

Police raid the Flamingo Jazz Club, Wardour Street, 1963

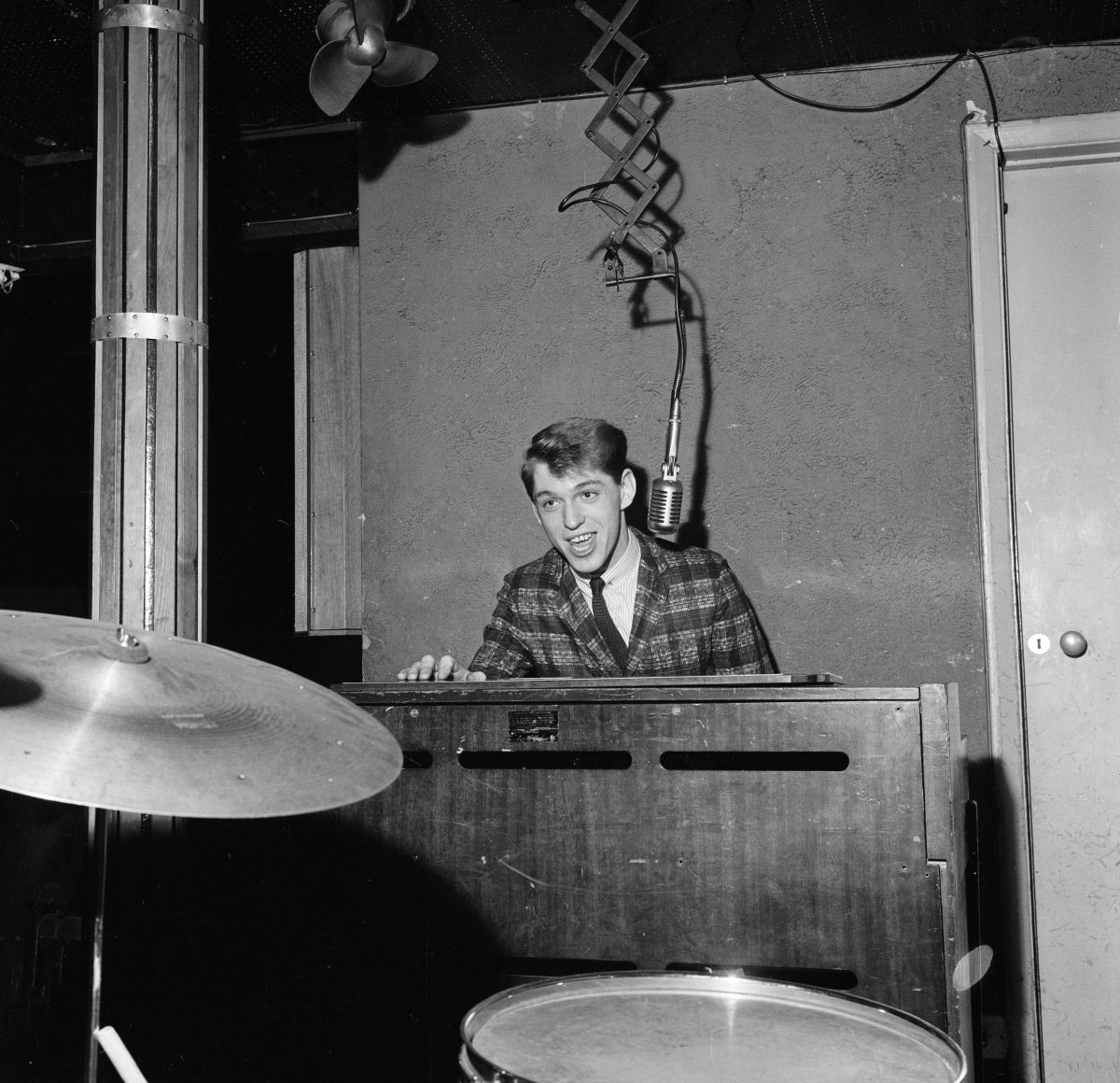

Georgie Fame, Flamingo Jazz Club, 33 Wardour Street, London photographed by Tony Frank, 1965

Arrest outside the Flamingo Club

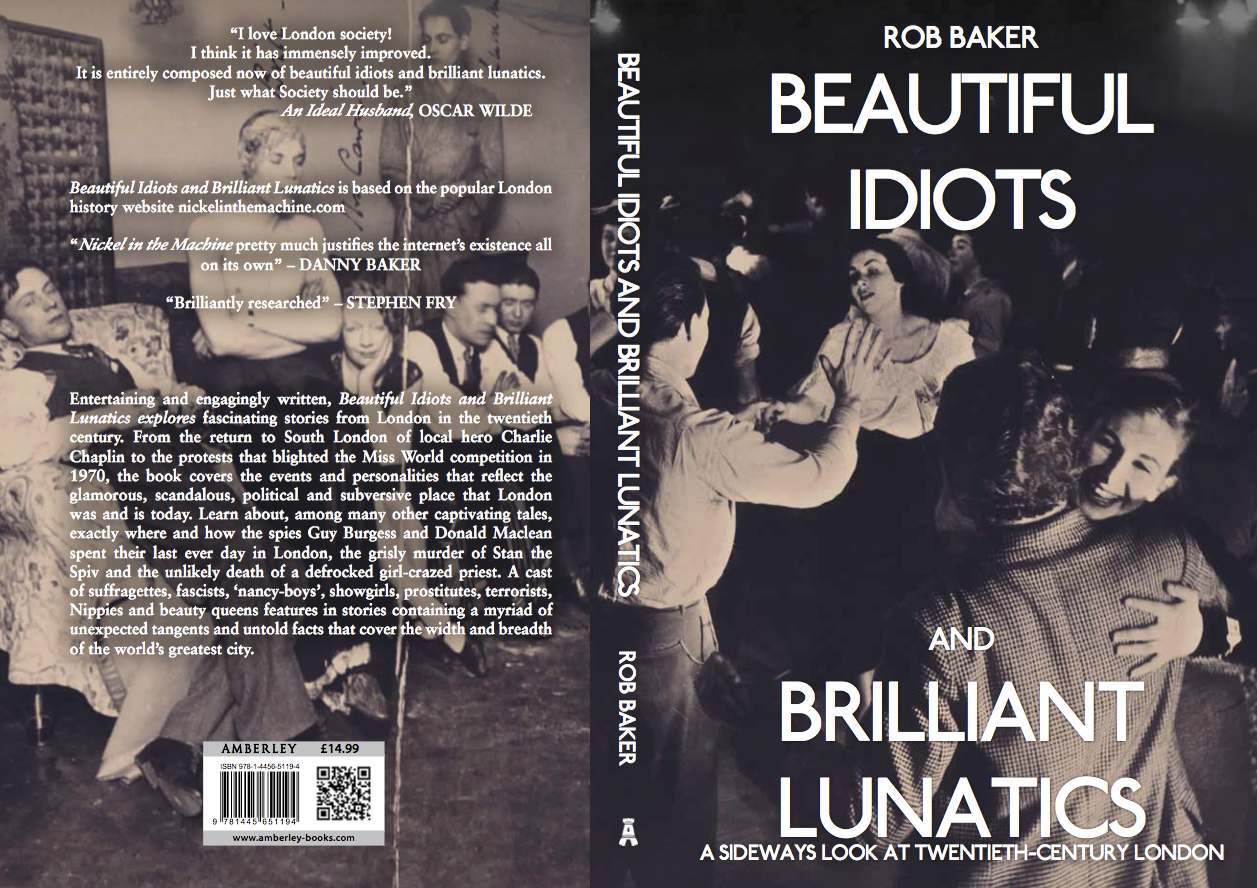

Excerpts in this article from Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics published by Amberley and featuring stories, characters and misfits from the 20th Century London.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.