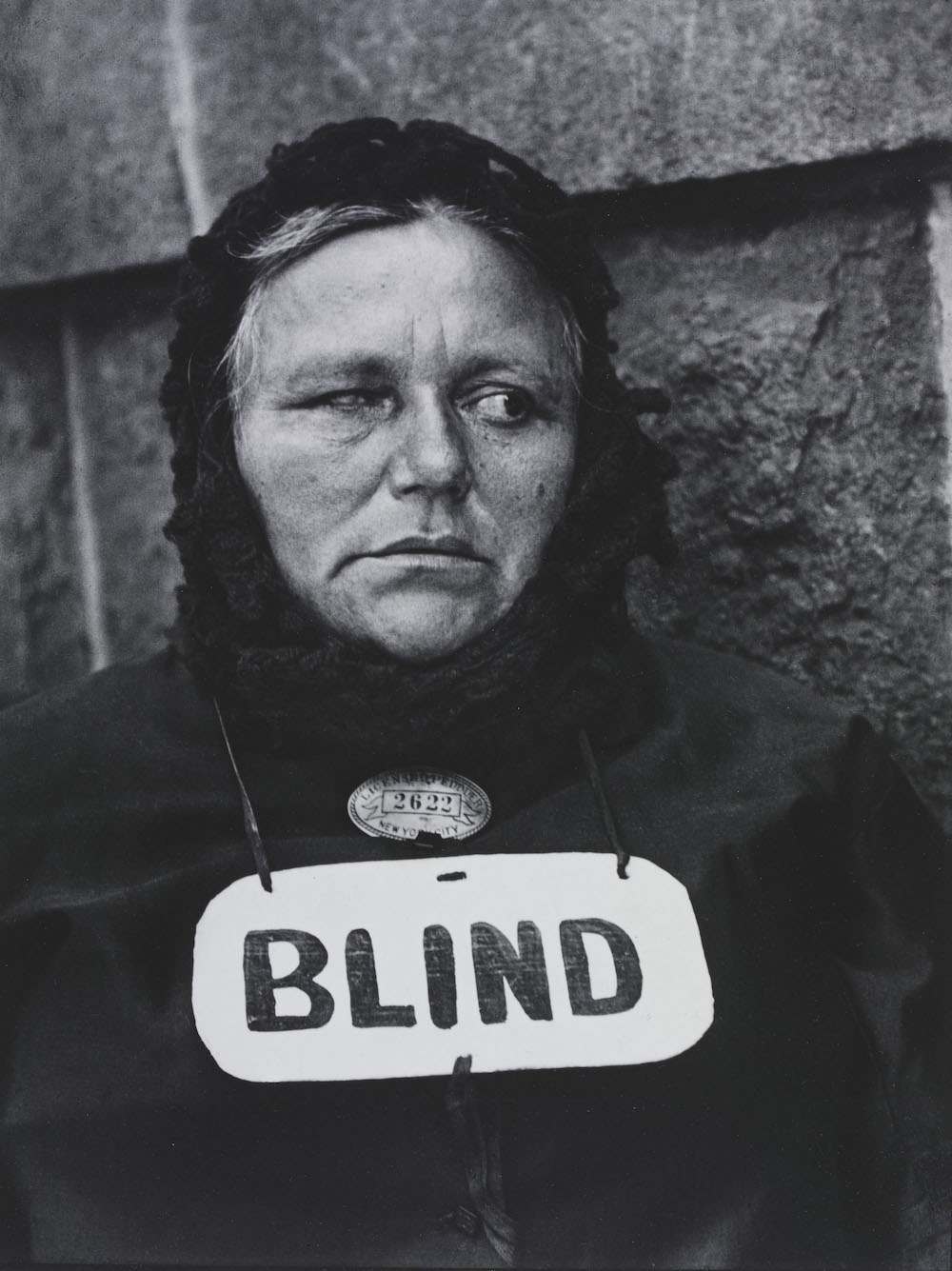

Goldie Williams was a rebellious woman arrested for vagrancy. She refused to unfold her arms and stop making this face (below) for her 1898 mugshot. She listed her occupation as a prostitute. But the crime of vagrancy was what caught her, a catchall that gave police virtually unlimited powers to arrest anyone in their line of vision.

Buy this print in the shop

Beginning in the mid 1800s, police photographed the faces of known criminals. Called “mugshots” (after the British slang word “mug” meaning “face”) these images replaced drawings and descriptions on wanted posters. Scientists even studied mug shots to see if physical traits could predict criminal behavior… The Omaha police photographed suspects when arrested. Whether the people depicted were guilty or innocent, behind every photograph is a human story.

Arrested on January 29, 1898, the police notes tell us that Williams, also known as Mag Murphy, stood just 5 feet tall and weighed 110 pounds. She listed her home as Chicago and her occupation as a prostitute. Her left index finger was broken and she had a cut below her right wrist. Williams sported an elaborate hat with satin ribbons and feathers. She wore large hoop earrings.

Now Risa Goluboff expands on how police could arrest pretty much anyone for vagrancy:

…the laws’ breadth and ambiguity gave the police virtually unlimited discretion. Because it was almost always possible to justify a vagrancy arrest, the laws provided what one critic called “an escape hatch” from the Fourth Amendment’s protections against arrest without probable cause. As one Supreme Court justice would write in 1965, vagrancy-related laws made it legal to stand on a street corner “only at the whim of any police officer.”

Second, vagrancy laws made it a crime to be a certain type of person—anyone who fit the description of one of those colorful Elizabethan characters. Where most American laws required people to do something criminal before they could be arrested, vagrancy laws emphatically did not.

Goldie Williams Leaves Chicago And The Persecution of Will Brown

And why was Goldie Williams, a black, African-American woman, not in Chicago?

Christy Hyman writes:

Omaha, Nebraska experienced sharp increases in population growth after 1880, with railroads and stockyards providing work opportunities for African Americans. It is this migration perhaps, that Williams followed from Chicago that lead her to Omaha. The railroads provided the largest number of job opportunities for African Americans with many of them finding employment as porters, cooks, and common laborers.

By 1910, Omaha had the third largest black population among the new western cities. By 1920, the black population more than doubled to over 10,000, second only to Los Angeles with nearly 16,000. Racism and fear fuelled confrontation. In 1919, Will Brown, a 41-year-old African-American was arrested as a suspect in the allege rape of a white woman. The victim identified Brown as the perpetrator of the assault, although the police and Army intelligence later reported that the identification was not positive.

Clayton D. Laurie, Ronald H. Cole take up the story:

The first attempt by a mob to lynch Brown was unsuccessful, but two days after his arrest rumors began to circulate that another attempt would be made on his life. On the afternoon of Sunday, 28 September, a group of approximately fifty youths from age fourteen to twenty, reputed to be friends of Loebeck’s, gathered at the Bancroft School in south Omaha and began a one-mile march to the downtown Douglas County Court House. By 1600 this group had been joined by a much larger crowd. Although initially good humored, the mob turned rapidly hostile, demanded that the prisoner be surrendered to them, and stoned the building, breaking all the windows on the first and second floors. These actions forced the forty-five Omaha policemen present to retreat to the third and fourth floors. The county jail was on the fifth floor. The mob then stormed the building. The police opened fire, killing two, but only succeeded in delaying the mob temporarily. Within minutes the situation had escalated far beyond the capacity of the police to control. The Army later estimated that by 1945 the crowd numbered some 5,000 people.

Throughout the confrontation, Omaha Mayor Edward P. Smith refused resolutely to surrender Brown, an effort that nearly cost him his life. As the mob surged onto the fourth floor of the courthouse, Smith, who was trying to calm the crowd, was seized, dragged from the building, and hoisted up a nearby trolley pole the mob intended to use as a makeshift gallows. The timely intervention of two police detectives, who cut the critically injured mayor down and rushed him away in a waiting automobile, saved him from certain death. Still intent on reaching the prisoner, the mob broke into hardware stores and pawnshops, seizing firearms and ammunition. By 2030 several rioters had looted a nearby gasoline station and seized fuel which they promptly used to set fire to the first several floors of the courthouse, hoping to burn out the police and Brown. Attempts by the fire department to extinguish the flames were thwarted. As the heat and smoke became intense, police authorities moved Brown and the other prisoners to the roof. At this point the mob finally captured Brown. The actual sequence of events remains unclear, but one account maintains that the prisoners on the roof, in spite of police efforts, surrendered Brown to save their own lives.

The mob then took Brown to the corner of 16th and Harney Streets, near the courthouse, hanged him, mutilated and riddled his body with bullets, dragged it through the streets of the city at the end of a rope, and burned it. Still not satisfied, the mob ransacked more stores in search of arms and then went to the nearby police station to lynch blacks being held there. After Brown was murdered, however, the police captain on duty at the jail released the other black prisoners, an action that undoubtably saved their lives.

The charred corpse of Will Brown after being killed, mutilated and burned. The burning of William Brown, Omaha, Neb., Sept. 28, 1919.

Goldie Williams And The Ugly Laws

And Chicago was no easy place to be Goldie Williams or anyone not fitting into the proscribed norms decreed by the local politicos. Nina Renata Aron looks at another law set up to purify the city’s streets:

In 1881, a Chicago alderman named James Peevey described the beggars on his city streets as human “street obstructions.” Peevey was instrumental in pushing an ordinance through the city council that prohibited any person who is “diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object” from being in the “public view.” A Chicago Tribune piece the same year said Peevey “proposes to abolish the woman with two sick children who… grinds ‘Mollie Darling’ incessantly.”

For the crime of being “unsightly,” beggars could be charged anywhere from $1 to $50 — or up to about $1100 in today’s dollars. Those who weren’t able to pay were sent to poorhouses…

The City Beautiful movement, an urban reform philosophy based on the idea that cities should be as aesthetically pristine as possible, was at its peak at the same time that ugly laws were being passed. It, too, was a response to the influx of immigrants, veterans, and newly freed slaves in many American cities, and its ethos blended well with that of urban charitable organizations. Together, they sought to produce a particular kind of city environment: one purportedly devoted to its own betterment and beautification where the poor and other unfortunates could rely on (some) benevolent support. But the emphasis on beauty and benevolence belied the true effect (and perhaps purpose) of these initiatives, which was to define the ideal citizen: one who was white, able-bodied, English-speaking, and sufficiently independent.

The ‘Ugly Law’ was repealed in 1974.

Susan M. Schweik has more on laws laced with the whiff of eugenics:

The first of these laws was introduced by the City of San Francisco on 9th July, 1867: “Order No. 783. To Prohibit Street Begging, and to Restrain Certain Persons from Appearing in Streets and Public Places” (Schweik 2009: 291). As the name of this ordinance suggests, ugly laws were concerned with more than appearance, prohibiting both the activity of street begging and the appearance in public of “certain persons”. The phrasing that one finds in the Chicago City Code in 1881 originates in this San Francisco law…

The ‘Ugly Law’ went nationwide:

Sometime around 1916, a woman known as “Mother Hastings” was told by authorities in Portland, Oregon that she was “too terrible a sight for the children to see.” “They meant my crippled hands, I guess,” she told a reporter. “They gave me money to get out of town.” (Los Angeles Times 1917). “Mother Hastings” complied, moving to Los Angeles just as that city’s leaders were discussing enacting a version of the city ordinance that had restricted her access to urban space in Portland. These laws closed city spaces across the United States to people we would now call disabled, through variants of the words with which we began: “No person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated or in any way deformed so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object or improper person to be allowed in or on the public ways or other public places in this city, or shall therein or thereon expose himself to public view.” These ordinances were panhandling law at their core. Unsightliness was a status offense, illegal only for people without means.

And unsightly could also mean the crime of bing black in public. W. Michael Byrd and Linda A. Clayton note:

“Black health plummeted due to the Civil War collapse of the slave health subsystem….In lieu of emancipation, the war and its aftermath represented a health catastrophe for African Americans as their health status fluctuated wildly until 1910. This led influential biostatisticians…as well as many in the medical profession, to confidently predict black extinction by the year 2000.”

Some background, then, on the era of Goldie Williams, a woman who wore the armour of respectability, never lost her sense of self and stood defiant.

BUY PRINTS of Goldie Williams in the Shop.

Via:

Mugshots of Smiling Killers And Defiant Criminals From 19th Century Nebraska

Vagrant Nation: Police Power, Constitutional Change, and the Making of the 1960s by Risa Goluboff.

The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public (History of Disability) (The History of Disability) by

An American Health Dilemma: Race, Medicine, and Health Care in the United States 1900-2000 by W. Michael Byrd and Linda A. Clayton.

The role of federal military forces in domestic disorders, 1877-1945 by Clayton D. Laurie, Ronald H. Cole

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.