There had been a small and relatively law-abiding Chinese community based around Limehouse from around the beginning of the 19th century. A hundred years later it had grown into two separate communities in the area. The Chinese from Shanghai were mostly based around Pennyfields and Ming Street (between the present Westferry and Poplar DLR stations) whereas the immigrants from Southern China and Canton lived generally around Gill Street and the Limehouse Causeway.

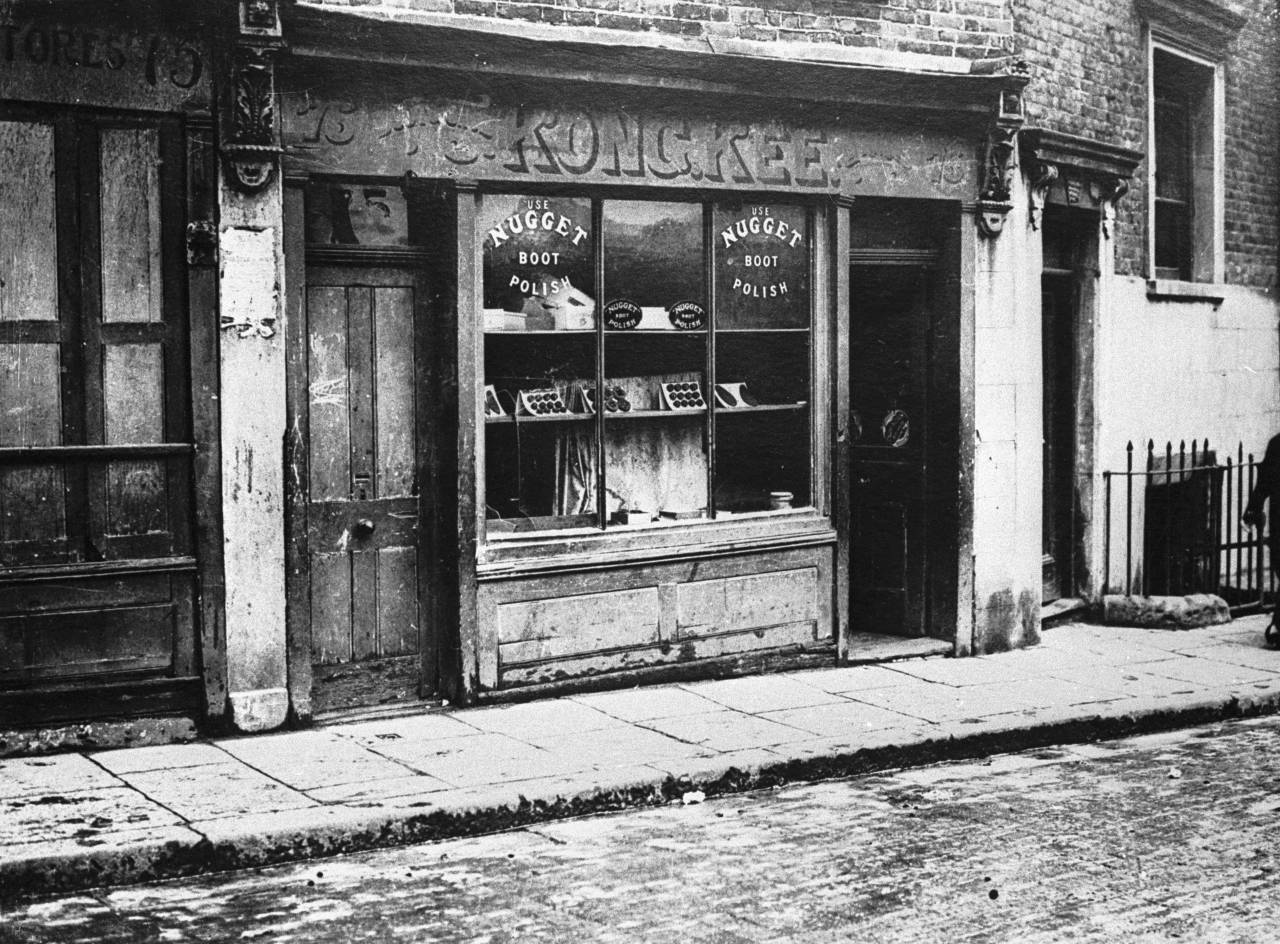

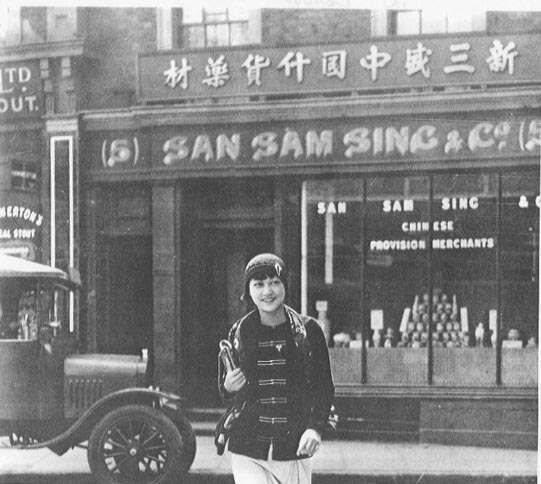

circa 1935: London’s Chinese quarter, Chinatown, in the 1930’s. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

Despite there being rarely more than a few hundred Chinese people living around Limehouse before and after the first world war (in fact Liverpool had a far larger Chinese population), the East End Chinatown had an extraordinarily bad reputation.

Newspapers and magazines wrote scandalous articles with lurid headlines about opium dens and the white-slave traders but numerous writers, novelists and even film-makers helped to greatly exaggerate the danger and immorality of the area. At times it seemed that Limehouse was almost singlehandedly responsible for corroding the moral backbone of the British middle-classes.

HV Morton the famous travel essayist and journalist wrote about Limehouse in his book The Nights of London in 1926:

The squalor of Limehouse is that strange squalor of the East which seems to conceal vicious splendour. There is an air of something unrevealed in those narrow streets of shuttered houses, each one of which appears to be hugging its own dreadful little secret… you might open a filthy door and find yourself in a palace sweet with joss-sticks, where queer things happen in a mist of smoke……The silence grips you, almost persuading you that behind it is something which you are always on the verge of discovering; some mystery of vice or of beauty, or of terror and cruelty.

April 1911: A street in China Town in London’s East End, home of the Wo Fung Goy Chinese cafe. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

The fact that the Chinese community liked to gamble and smoke opium was bad enough but it seemed to be the fear of sexual contact between the races (which the drug-taking of course only exacerbated) that frightened so many people. Especially the newspaper editors of the time. ‘White Girls Hypnotised by Yellow Men’ shouted the Evening News, writing that it was the duty ‘of every Englishman and Englishwoman to know the truth about the degradation of young white girls’.

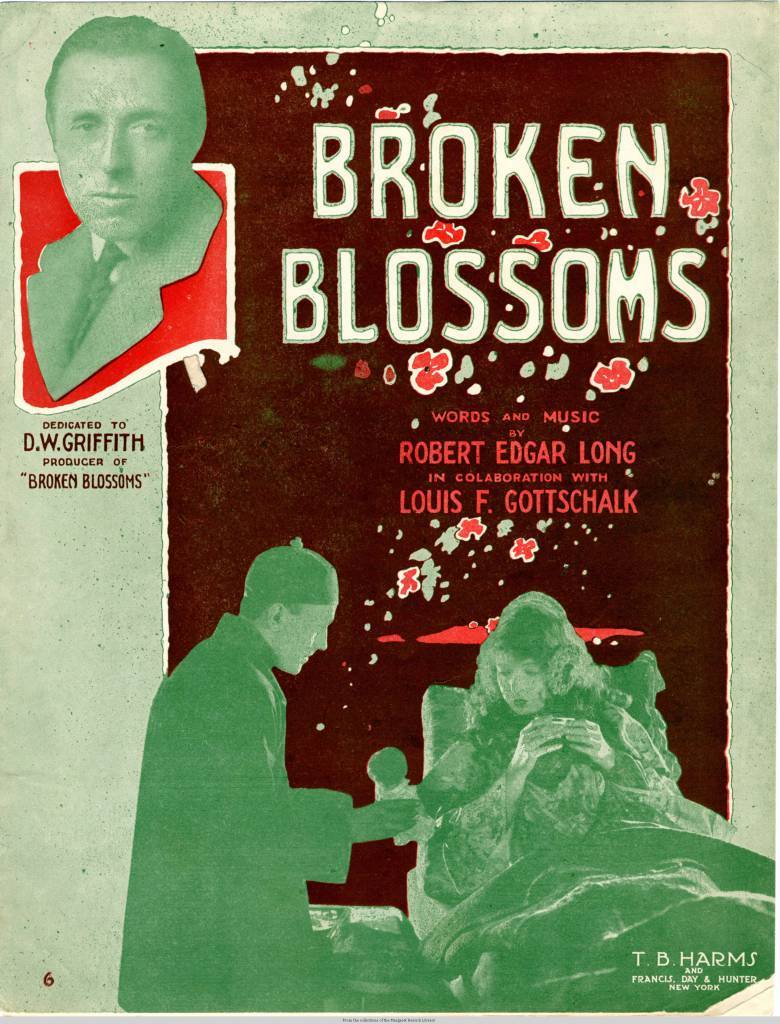

Thomas Burke, writing for uneasy suburban readers that lapped up his writings, even in the US, wrote a number of ‘sordid and morbid’ short stories and newspaper articles about the Limehouse Chinatown. One of his stories, from a collection entitled Limehouse Nights, was called ‘The Chink and the Child’ and was actually made into a successful film called ‘Broken Blossoms by DW Griffiths starring Lilian Gish.

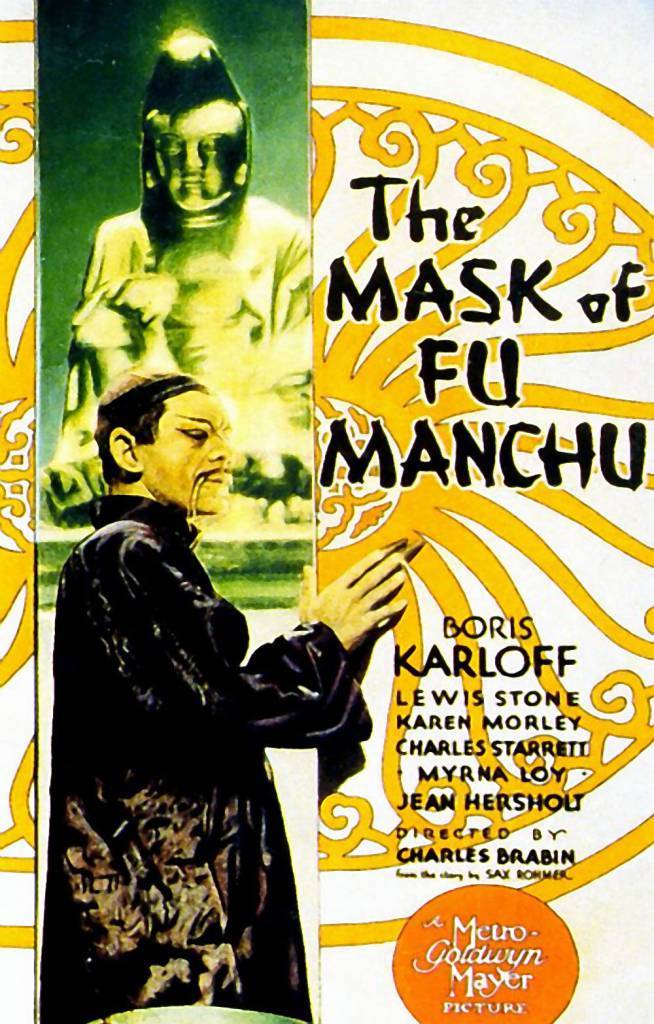

Sax Rohmer was another former journalist that used his knowledge of Limehouse to write popular fiction, notably the incredibly successful Fu Manchu novels about a depraved Chinese man whose evil empire’s headquarters was based, rather improbably, in Limehouse:

Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present…Imagine that awful being and you have a mental picture of Dr Fu Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man.

Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu stories went on to inspire over thirty films and television series throughout the following decades. However Rohmer also wrote a novel called Dope in which a character called Rita Dresden was unashamedly based on Billie Carleton. A silly socialite in the same novel called Mollie Gretna envies the Scottish wife of the Chinese drug dealer:

I have read that Chinamen tie their wives to beams in the roof and lash them with leather thongs. I could die for a man who lashed me with leather thongs. Englishmen are so ridiculously gentle to women!

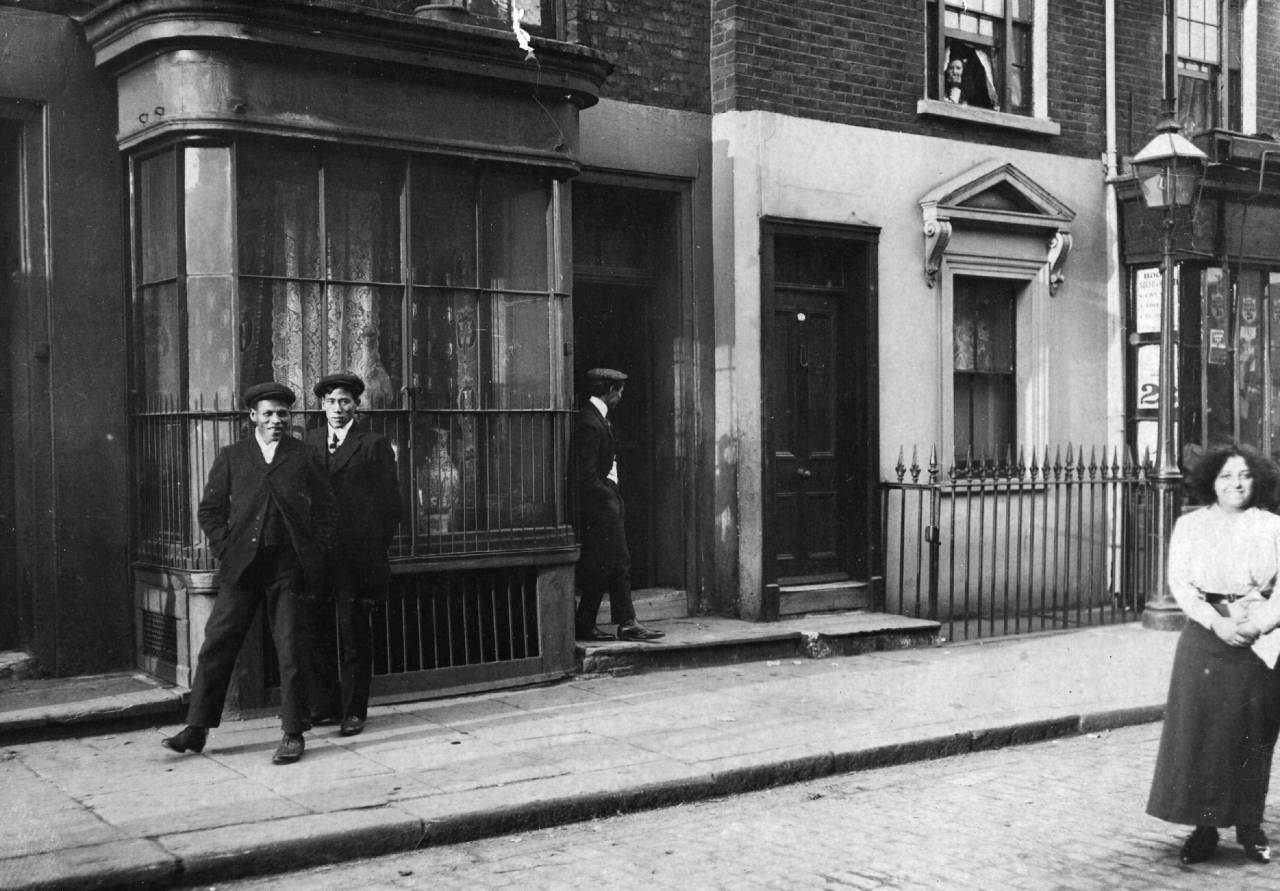

Two Chinese men meet on a street corner in China Town in London’s East End. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.