THE Beatles At The BBC.

London calling all “Beatle People”

TWO decades ago, the Great Beatles Revival began with the release of the double CD album Live at the BBC. Like their regular albums, it duly hit number one on both sides of the Atlantic, and shifted no fewer than five million copies in the couple of months. Now the original set has been remastered and reissued simultaneously with a further collection: On Air – Live at the BBC Volume 2.

Both sets consist of radio interviews and performances from the mid-Sixties, and together they provide a fascinating picture of the biggest band of all time – at a time when such a concept was meaningless. This is an evocative and fascinating reminder of an era in which the Beatles were making their own rules, and bursting exponentially from the cosy confines of post-war light entertainment like a small child outgrowing successive pairs of shoes.

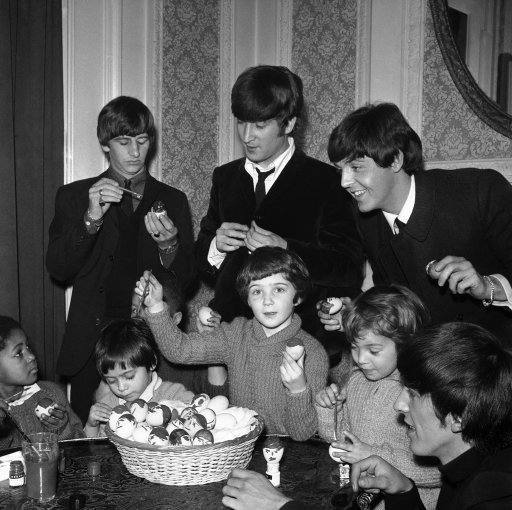

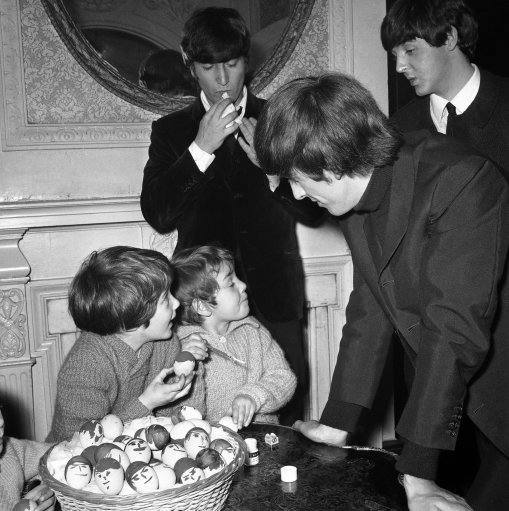

Photos above and below: The Beatles provide both inspiriting and instruction for Church of England Children’s society orphans as they paint mop topped Easter eggs during a visit with the Beatles at London’s Scala Theatre in England on March 25, 1964, where the mop group is currently filming scenes for their first motion picture. Beatles from left: Ringo Starr, John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison.

The chat is charming, and sometimes thought-provoking. The performances are always lively and often superb. “There’s a lot of energy and spirit,” says Sir Paul McCartney, after hearing them again. “We are going for it, not holding back at all, trying to put in the best performance of our lifetimes.”

This urgency was understandable. In 1963, less than a year into their recording career, the Beatles were asked about their prospects. Paul McCartney suggested that he and John Lennon might become professional songwriters for other acts. George Harrison hoped to have enough money “to go into a business of my own by the time we do flop”. And Ringo Starr had already set his sights on a string of hairdressing salons. It was hardly surprising that they were thinking ahead: the group had already exceeded expectations by achieving two chart-topping singles and a number one album, and the experience of previous acts suggested that the “flop” would come sooner rather than later. “How long are we going to last?” pondered Lennon. “You can be bigheaded and say, ‘Yeah, we’re going to last 10 years’, but as soon as you’ve said that you think: ‘We’re lucky if we last three months’.”

Photo: A casualty is revived with smelling salts after fainting at the Wimbledon fan club convention

Brian Epstein may have sold his “boys”, but apart from a wardrobe makeover (sorely resented by Lennon) he never tried to fundamentally change them. Geographically, they were 200-odd miles away from the Denmark Street impresarios with their teen idol fodder. In every other sense, they were from another planet. The likes of Larry Parnes looked for malleable young men to turn into two-dimensional pin-ups. The Beatles, by contrast, were already seasoned veterans of unforgiving northern clubs and the wild bars of Hamburg’s Reeperbahn. They were clever, talented, funny, self-assured and ambitious. Crucially, they were also a tight-knit group whose close relationship had seen them through a hard apprenticeship and given them the resilience to overcome the initial knock-backs. They backed their own talent and did it their way.

This ambition was tempered by self-awareness and self-deprecation, which only added to their appeal. Their self-confidence was allied to a down-to-earth, approachable image, symbolising a new era in which being ambitious and working-class was no longer seen as a contradiction in terms. This comes across in spades on these recordings, as they trade banter with avuncular BBC presenters like Brian Matthews, with whom they built an amiable relationship that is clearly based on mutual respect. (For all their old-fashioned shirt-and-tie appearance, Matthews’ Light Programme generation were far less patronising than the repulsive egomaniacal “disc jockeys” who would replace them after the creation of Radio 1 in 1967.

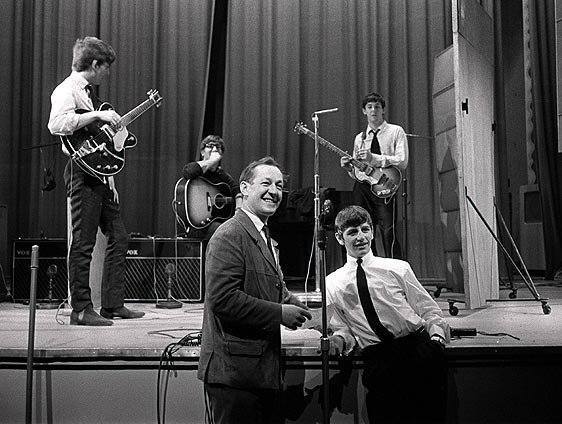

Photo: Brian Matthews “With The Beatles”

In many ways this relationship mirrored their relationship with their record label. EMI was a company of the old school – its recording engineers wore collar-and-tie and white lab coats. At the height of “Swinging London”, Beatles producer George Martin could have passed for a grammar school master. Studio practices were similarly strict, with manuals setting out rules on how to record. Yet the relationship between these consummate professionals and the enthusiastic youths who landed in their laps shows how the tension between discipline and self-expression can stimulate, rather than stifle, artistic development.

Photo: Charmer Paul bridges the ‘generation gap’

The Beatles knew how to play the game, but they played it on their own terms. Even as they were clasped to the nation’s bosom, they maintained their spikiness, and Lennon was enough of a loose cannon to give every encounter an edge. His most famous quip, when he invited the Queen Mother to “rattle your jewellery” during a live televised Royal Command Performance, is often used as an evidence of the group’s cheeky charm. Less well known is the fact that Epstein was on the verge of a heart attack in the wings because Lennon had threatened to tell the Queen Mum to “rattle your fucking jewellery”. In the event Lennon managed to have it both ways, as Beatles usually did.

This combination of ambition and character was not just a case of disarming journalists and winning hearts and minds: it was crucial to the music itself. At their early hard-won recording sessions they had the balls to turn down material they were given by George Martin and put their own songs forward instead. Right from the start, their personality shone through: there was never any mistaking the Beatles sound, and it comes across here loud and clear, even live performances and hastily recorded sessions with no real “production”.

The group played 88 distinct songs in their BBC sessions – some of which were re-recorded in different versions as the months went by and demand for personal appearances grew. Between March 1962 and June 1965, no fewer than 275 unique musical performances by The Beatles were broadcast by the BBC in the U.K. The group played songs on 39 radio shows in 1963 alone. On one day in July 1963, they recorded an extraordinary 18 songs for three editions of their Pop Go The Beatles.

“We used to drive 200 miles in an old van down the M1, come into London, try and find the BBC and then set up and do the programme,” recalled George Harrison years later. “Then we’d probably drive back to Newcastle for a gig in the evening!”

This level of activity is pretty impressive in itself, but it becomes quite remarkable when placed in the context of the band’s overall workload. In the period 1963 to 1965 they released six albums (plus non-album singles), made two feature films and played more than a thousand concerts. In their spare time, they wrote hits for other artists.

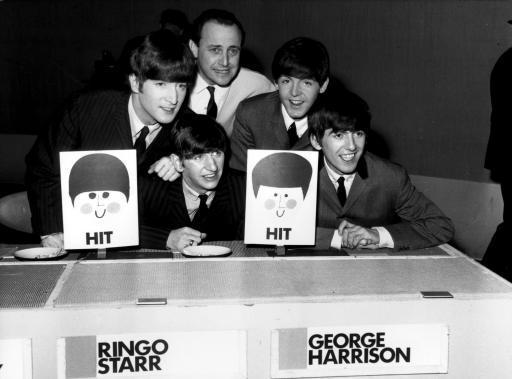

Photo: The hit-makers adjudicate on Juke Box Jury with David Jacobs

With such a workload, they could have been forgiven for letting standards slip. Yet the overall quality was amazing. Every album has at least one single-that-never-was, and several songs strong enough to become hits for others. Even the “filler” is better than other bands’ best material. Their singles rewrote the rulebook, too – particularly the B-sides, which had traditionally played the ‘piece of shit’ role to lucrative effect. Beatles’ flipsides like ‘Rain’ and ‘I Am The Walrus’ were superior to most ‘greatest hits’, while their stand-alone double-A-sides – Day Tripper/We Can Work It Out and Penny Lane/ Strawberry Fields Forever – were two of the best singles ever made.

This collection features many of their early self-penned classics, many of which had been written and recorded in a matter of hours. The re-recorded versions here are sometimes better than originals, possibly as a result of having been performed regularly in then meantime. It comes as something of a shock, for example, to hear If I Fell without McCartney loudly fluffing the high note in the chorus, as he does on the album version…

Like most bands of the time, they were influenced by Fifties stalwarts like Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Carl Perkins and the Everley Brothers, and their debt to rockabilly and country is obvious on their first six albums. But they were quick to pick up on new developments, too, and covered several Brill Building hits by the early Sixties ‘girl groups’. (As early champions of Tamla pioneers like Smokey Robinson and Marvin Gaye, they helped to broaden the appeal of many other artists in the process.) Whatever material they chose, though, it always ended up sounding like a Beatles song.

This ability to impose their personality was helped considerably by their distinctive vocals. Lennon possessed one of the greatest rock voices of all time, and it was enhanced by the way it melded with McCartney’s and, to a lesser extent, Harrison’s. Individually, too, each Beatle was instantly recognisable. And unlike the Elvis wannabes, they sang in their own accents in a way that was both unusual and completely natural. The overall result was a new and unique sound

Their first album was a polished representation of their live act – a stunning mixture of quality covers and original gems. Yet it was the already just the tip of the iceberg. As the BBC sessions show, they had enough cover versions to release at least two alternative albums which would have blown away the contemporary opposition. Listening to it now, one gets a glimpse of the Beatles as a live club band –of whom Motorhead’s Lemmy, who saw them in their Cavern days, says: “They were magic. They were monstrous, perfect. I always thought The Beatles were the best band in the world.”

Not only did the boys have an embarrassment of riches from their live act – they had self-penned songs to spare. Throughout the 1960 they provided a stream of smash hits for other artists, most of whom failed dismally to do the songs justice. One example from the BBC sums it up. Compare Billy J Kramer and The Dakotas’ polished studio version of “I’ll Be On My Way” (a minor McCartney composition) with The Beatles’ off the cuff version, which wouldn’t have been out of place on Beatles For Sale…

Last but not least, and one of the most neglected aspects of the Beatles’ appeal, is their sense of humour. Broadcasts and press conferences were lit up by their repartee, to the extent that the media were completely disarmed. This and the best efforts of the emollient Epstein were usually enough to ensure that the press turned a blind eye to Lennon’s acerbic quips, simmering aggression, and uncontrollable urge to do “spastic” impersonations on stage and Nazi salutes from balconies.

Their humour won over George Martin, too, and they in turn were impressed that he produced the Goons. His comedy sound effects were used to good effect on the amusing fan club records as well as novelty tracks like Yellow Submarine. The general atmosphere of the Beatles’ studio sessions owes something to this tradition, with banter conducted in silly voices, and jokes slipped into many ‘serious’ tracks – partly, no doubt, to puncture any suggestion of pretentiousness. Lennon’s self-pitying Girl’ includes a schoolboyish backing vocal by McCartney (“tit, tit, tit”), while Revolution No 9 – easily the most controversial and anger-provoking track in the Beatles catalogue – is similarly undercut by the tongue-in-cheek lullaby Goodnight which follows. Here, as one might expect in early BBC recordings, it is the whimsy and the Goons that predominate. Nevertheless, there is a wry self-assurance in evidence, which would provide a template for less talented and less witty rock stars who would follow in the Beatles’ footsteps.

The overwhelming impression left by these four discs is one of innocent(ish) fun. The last word goes to a young fan interviewed before the Shea Stadium concert in August 1966. “The Beatles bring joy to the world,” she smiled. “We forget our cares when we hear Beatle records.” These albums are further proof, if needed, of this enduring truth.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.