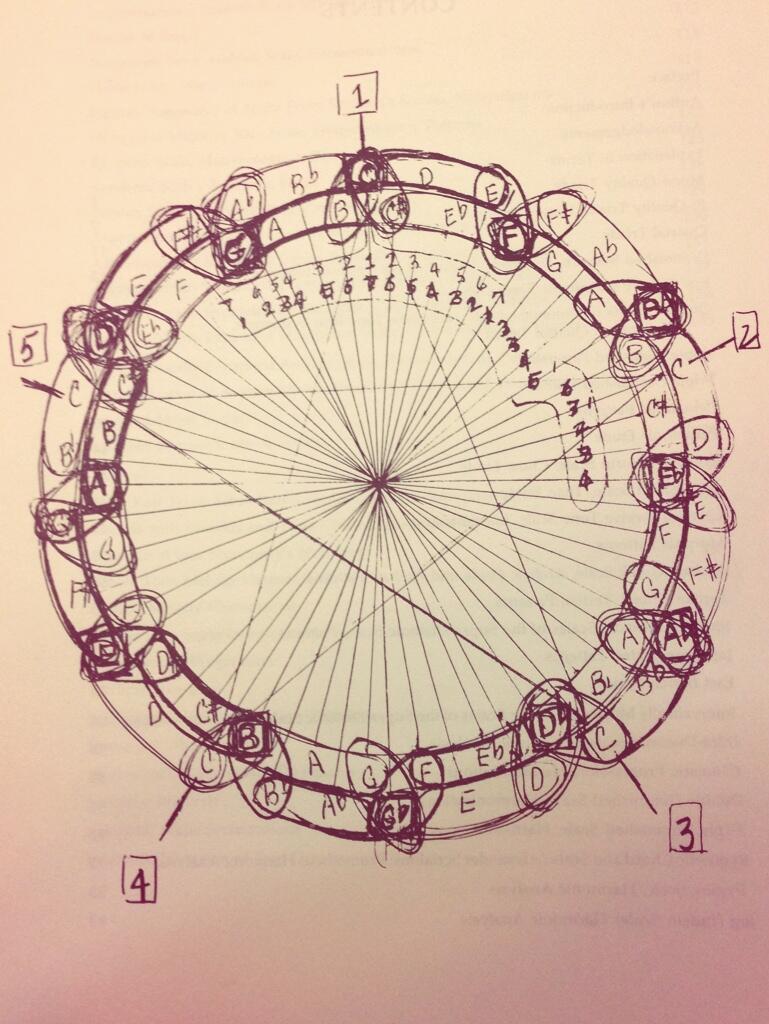

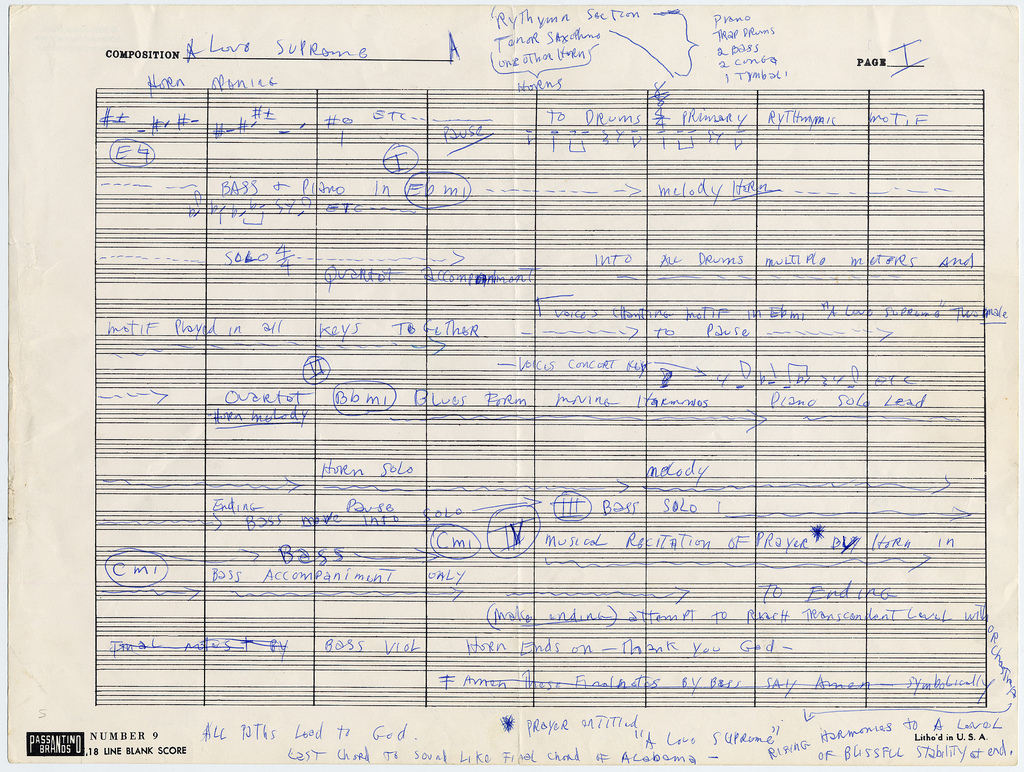

The Coltrane Circle, named after John Coltrane, was the jazz musician’s gift to saxophonist and professor Yusef Lateef in 1967. Coltrane produced it between set breaks at a gig.

In Repository of Scales and Melodic Patterns, Lateef regards the link between mathematics and music. He notes in his autobiography that Coltrane’s music was a “spiritual journey” that “embraced the concerns of a rich tradition of autophysiopsychic music” – a quality Lateef defined as, “Music which comes from one’s physical, mental and spiritual self.”

One sensation leads to another, causing a synesthetic reaction that helps us better to connect with the world and enliven us to the harmonious whole of everything. It’s all about communication, right? And mathematics, at once exact and abstract, invites a connection between numerical concepts and the way we sense and experience.

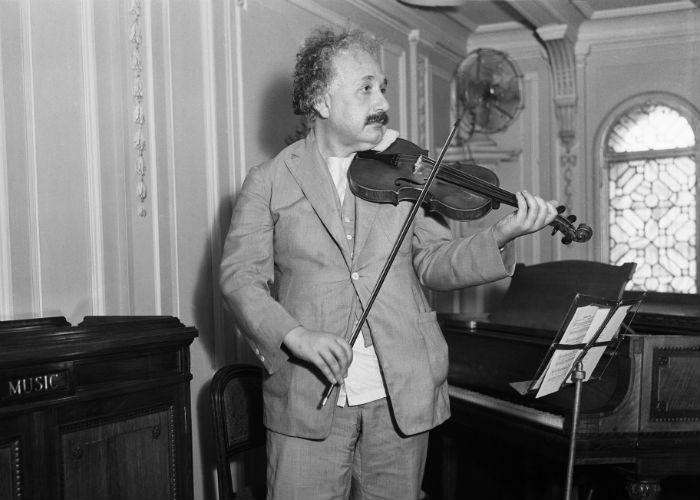

Josh Jones makes the connection between the sublime Coltrane and the 20th Century’s most recognisable genius, Albert Einstein, a keen violinist:

Coltrane was also very much aware of Einstein’s work and liked to talk about it frequently. Musician David Amram remembers the Giant Steps genius telling him he “was trying to do something like that in music.”

Coltrane was showing us the universe’s harmonies – taking us with him on Lateef’s “spiritual journey”. As Einstein noted, via Einstein and the Poet: In Search of the Cosmic Man:

“Reading Kant, I began to suspect everything I was taught. I no longer believed in the known God of the Bible, but rather in the mysterious God expressed in nature.

“The basic laws of the universe are simple, but because our senses are limited, we can’t grasp them. There is a pattern in creation.

“If we look at this tree outside whose roots search beneath the pavement for water, or a flower which sends its sweet smell to the pollinating bees, or even our own selves and the inner forces that drive us to act, we can see that we all dance to a mysterious tune, and the piper who plays this melody from an inscrutable distance—whatever name we give him—Creative Force, or God—escapes all book knowledge.

“Science is never finished because the human mind only uses a small portion of its capacity, and man’s exploration of his world is also limited.”

He concluded:

“I do not need any promise of eternity to be happy. My eternity is now. I have only one interest: to fulfill my purpose here where I am. This purpose is not given me by my parents or my surroundings. It is induced by some unknown factors. These factors make me a part of eternity.”

Einstein attributed his scientific insight and intuition to music.

“If I were not a physicist,” he once said, “I would probably be a musician. I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music…. I get most joy in life out of music”. His son, Hans, amplified what Einstein meant by recounting that “[w]henever he felt that he had come to the end of the road or into a difficult situation in his work, he would take refuge in music, and that would usually resolve all his difficulties”. After playing piano, his sister Maja said, he would get up saying, “There, now I’ve got it” . Something in the music would guide his thoughts in new and creative directions.

Do the hard thinking and when you relax and let loose, you get to reach further. Lateef noted in teaching his Autophysiopsychic Music method that “the student must know as a prerequisite the following aspects of musical theory:

a. major and minor scales

b. major and minor triads

c. major and minor chords

d. augmented and diminished chords

e. intervals

f. form

g. melody and rhythm

h. elementary knowledge of keyboard harmony”

After mastering the known, intuition can take hold. Inspiration arrives as if by magic. Einstein called it “combinatory play”. In 1945, Einstein wrote on the mental processes of famous scientists:

My Dear Colleague:

In the following, I am trying to answer in brief your questions as well as I am able. I am not satisfied myself with those answers and I am willing to answer more questions if you believe this could be of any advantage for the very interesting and difficult work you have undertaken.

(A) The words or the language, as they are written or spoken, do not seem to play any role in my mechanism of thought. The psychical entities which seem to serve as elements in thought are certain signs and more or less clear images which can be “voluntarily” reproduced and combined.

There is, of course, a certain connection between those elements and relevant logical concepts. It is also clear that the desire to arrive finally at logically connected concepts is the emotional basis of this rather vague play with the above-mentioned elements. But taken from a psychological viewpoint, this combinatory play seems to be the essential feature in productive thought — before there is any connection with logical construction in words or other kinds of signs which can be communicated to others.

(B) The above-mentioned elements are, in my case, of visual and some of muscular type. Conventional words or other signs have to be sought for laboriously only in a secondary stage, when the mentioned associative play is sufficiently established and can be reproduced at will.

(C) According to what has been said, the play with the mentioned elements is aimed to be analogous to certain logical connections one is searching for.

(D) Visual and motor. In a stage when words intervene at all, they are, in my case, purely auditive, but they interfere only in a secondary stage, as already mentioned.

(E) It seems to me that what you call full consciousness is a limit case which can never be fully accomplished. This seems to me connected with the fact called the narrowness of consciousness (Enge des Bewusstseins).

‘Mathemusician’ Vi Hart has more on the synthesis between space, time, energy and music:

Music has two recognizable dimensions — one is time, and the other is pitch-space. … There [are] a few things to notice about written music: Firstly, that it is not music — you can’t listen to this. … It’s not music — it’s music notation, and you can only interpret it into the beautiful music it represents.

If music is so vital, is there a need to learn how to listen to it?

Elliott Scwharz puts the case for learning how to listen in Music: Ways of Listening:

- Develop your sensitivity to music. Try to respond esthetically to all sounds, from the hum of the refrigerator motor or the paddling of oars on a lake, to the tones of a cello or muted trumpet. When we really hear sounds, we may find them all quite expressive, magical and even ‘beautiful.’ On a more complex level, try to relate sounds to each other in patterns: the successive notes in a melody, or the interrelationships between an ice cream truck jingle and nearby children’s games.

2. Time is a crucial component of the musical experience. Develop a sense of time as it passes: duration, motion, and the placement of events within a time frame. How long is thirty seconds, for example? A given duration of clock-time will feel very different if contexts of activity and motion are changed.

3. Develop a musical memory. While listening to a piece, try to recall familiar patterns, relating new events to past ones and placing them all within a durational frame. This facility may take a while to grow, but it eventually will. And once you discover that you can use your memory in this way, just as people discover that they really can swim or ski or ride a bicycle, life will never be the same.

4. If we want to read, write or talk about music, we must acquire a working vocabulary. Music is basically a nonverbal art, and its unique events and effects are often too elusive for everyday words; we need special words to describe them, however inadequately.

5. Try to develop musical concentration, especially when listening to lengthy pieces. Composers and performers learn how to fill different time-frames in appropriate ways, using certain gestures and patterns for long works and others for brief ones. The listener must also learn to adjust to varying durations. It may be easy to concentrate on a selection lasting a few minutes, but virtually impossible to maintain attention when confronted with a half-hour Beethoven symphony or a three-hour Verdi opera.

Composers are well aware of this problem. They provide so many musical landmarks and guidelines during the course of a long piece that, even if listening ‘focus’ wanders, you can tell where you are.

[…]

6. Try to listen objectively and dispassionately. Concentrate upon ‘what’s there,’ and not what you hope or wish would be there. At the early stages of directed listening, when a working vocabulary for music is being introduced, it is important that you respond using that vocabulary as often as possible. In this way you can relate and compare pieces that present different styles, cultures and centuries. Try to focus upon ‘what’s there,’ in an objective sense, and don’t be dismayed if a limited vocabulary restricts your earliest responses.

[…]7. Bring experience and knowledge to the listening situation. That includes not only your concentration and growing vocabulary, but information about the music itself: its composer, history and social context. Such knowledge makes the experience of listening that much more enjoyable.

There may appear to be a conflict between this suggestion and the previous one, in which listeners were urged to focus just on ‘what’s there.’ Ideally, it would be fascinating to hear a new piece of music with fresh expectations and truly innocent ears, as though we were Martians. But such objectivity doesn’t exist. All listeners approach a new piece with ears that have been ‘trained’ by prejudices, personal experiences and memories. Some of these may get in the way of listening to music. Try to replace these with other items that might help focus upon the work, rather than individual feelings. Of course, the ‘work’ is much more than the sounds heard at any one sitting in a concert hall; it also consists of previous performances, recorded performances, the written notes on manuscript paper, and all the memories, reviews and critiques of these written notes and performances, ad infinitum. In acquiring information about any of these factors, we are simply broadening our total awareness of the work itself.

Finally, Michael Levi has created this video to show how music awakens the mind.

;

Via: Open Culture and BrainPickings. Roel Hollander has a great post on interpreting Coltrane’s digram.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.