“Herein lies the reason for the equivocal effect of grotesque art on many people: the material is unfamiliar, and, by ordinary standards, unpleasant: yet it calls forth a deep instinctive response. Thus they are torn between repulsion and attraction”

– William Mortensen

In the 1920s, William Mortensen (January 27, 1897 — August 12, 1965) was living in his native Utah when he met the then aspiring actress Fay Wray (September 15, 1907 – August 8, 2004) and her older sister, Willow. When the girls moved to Los Angeles, he accompanied them as Fay’s chaperon and Willow’s fiance. On the journey he spoke of his attraction toward Fay, and that he was more interested in her than Willow.

Fay later admitted: “I felt odd, as old as a fourteen-year-old could feel. I felt happy that he admired me; I felt guilty that he did. The train rushed on and my face felt hot. I stared at the pattern in the combing jacket. To hear that he had not cared for my sister, as my mother had said, made me feel awful, even though I liked hearing what he had to say about me. I was feeling an appreciation of myself beyond what I had ever felt; at the same time, it was terribly uncomfortable to feel so old.”

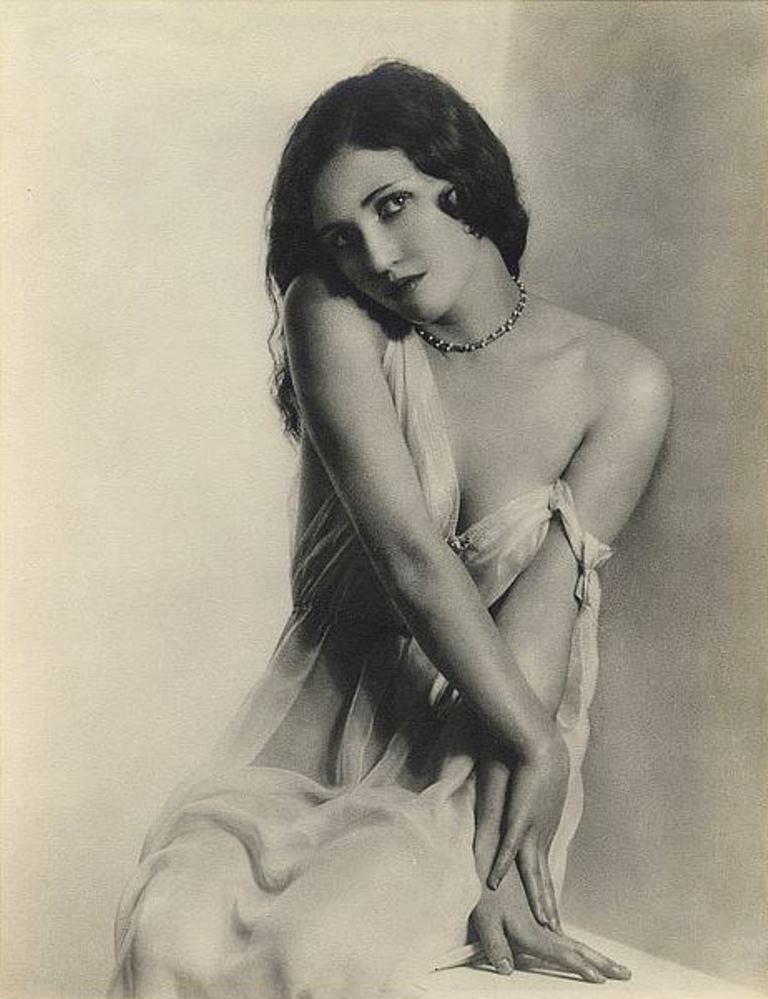

While in Hollywood, Mortensen took photos of Fay in various dresses (photo above) at the Wetzel studio. Another time, he took her to the beach where he took pictures of her showing a lot more skin.

It may not overly surprise you to know that Mortensen and Willow never did marry. Willow and Fay’s mother, Elvina, a native of Utah, feared Mortensen had molested her youngest daughter. She asked to see all of the glass plates he’d taken of Fay. Mortensen brought them to her. And Elvina broke them. Faye would go on to say that there had been no sexual abuse at all. But the damage was done.

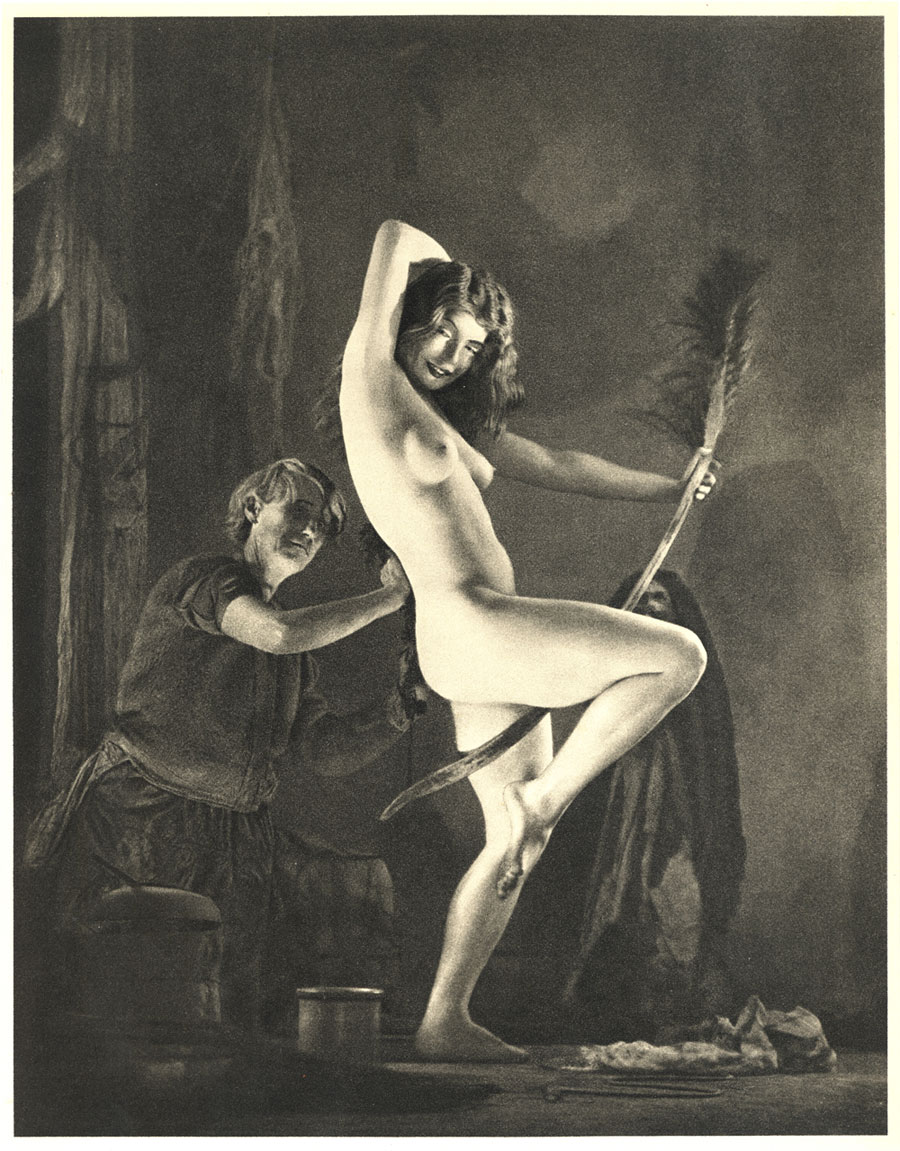

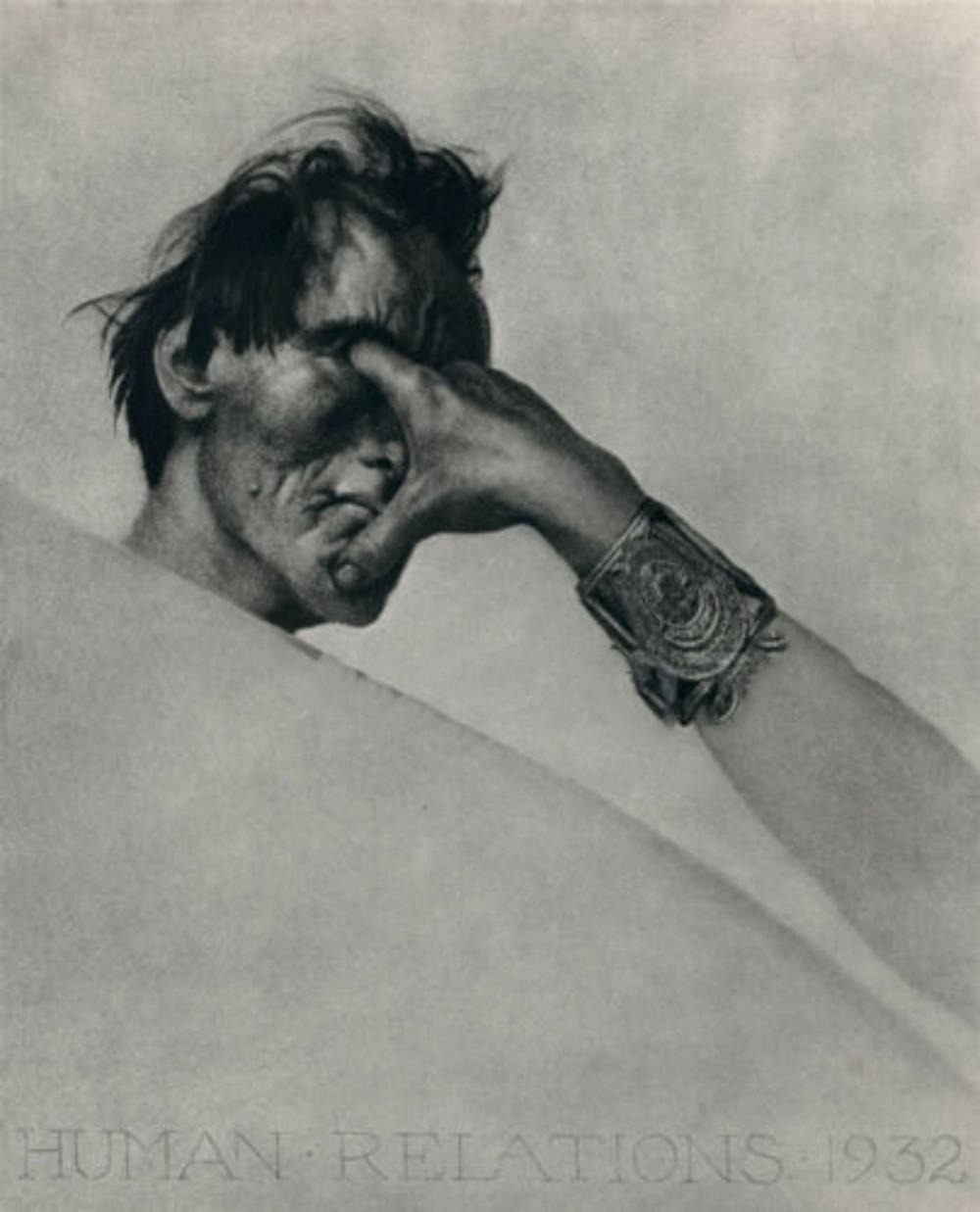

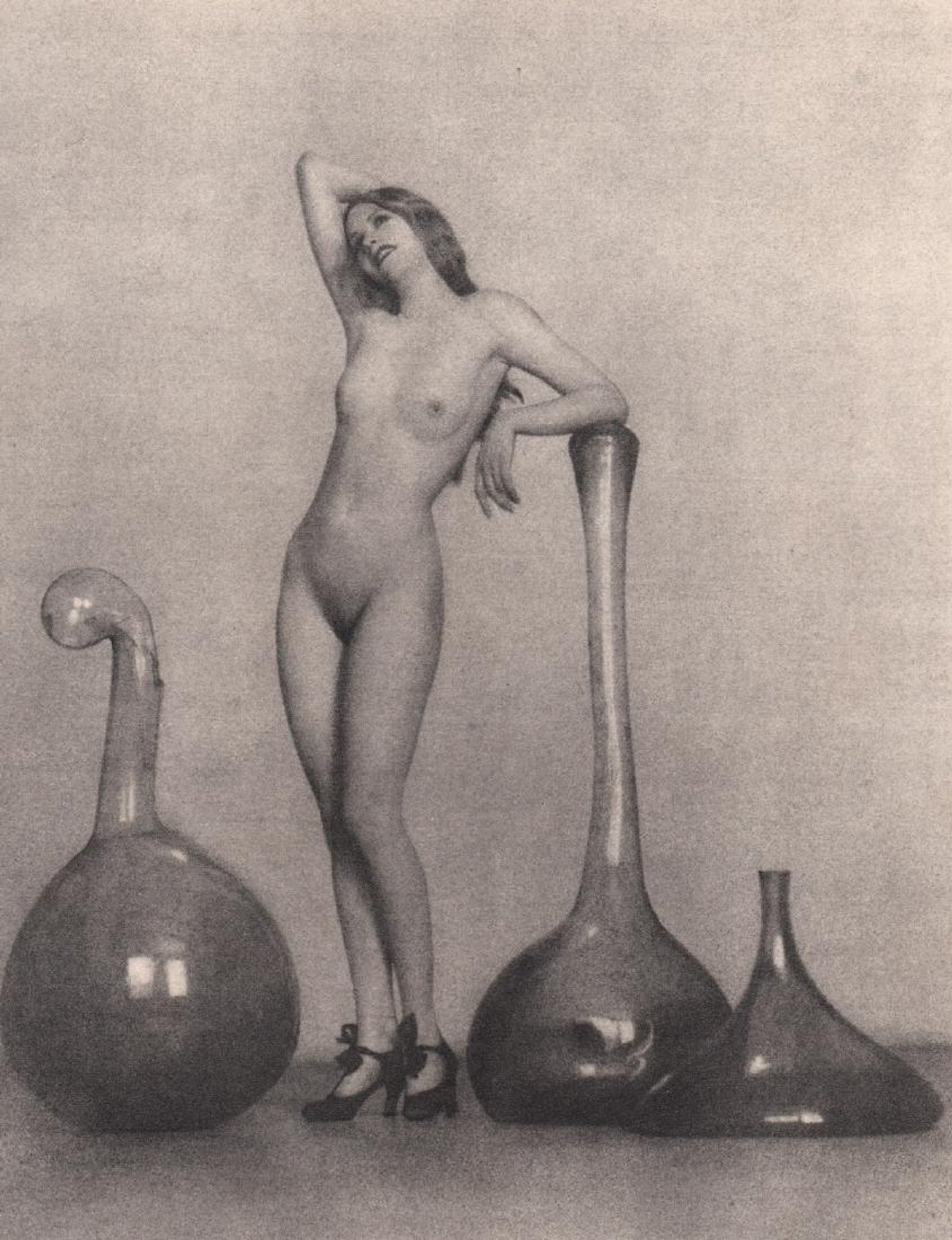

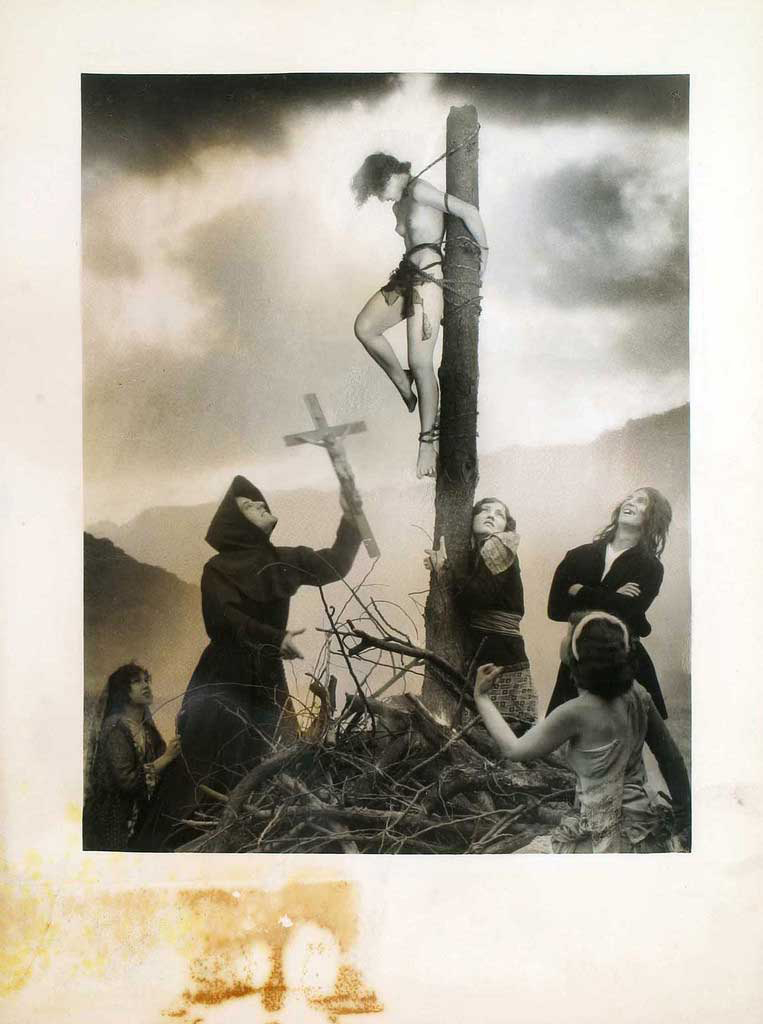

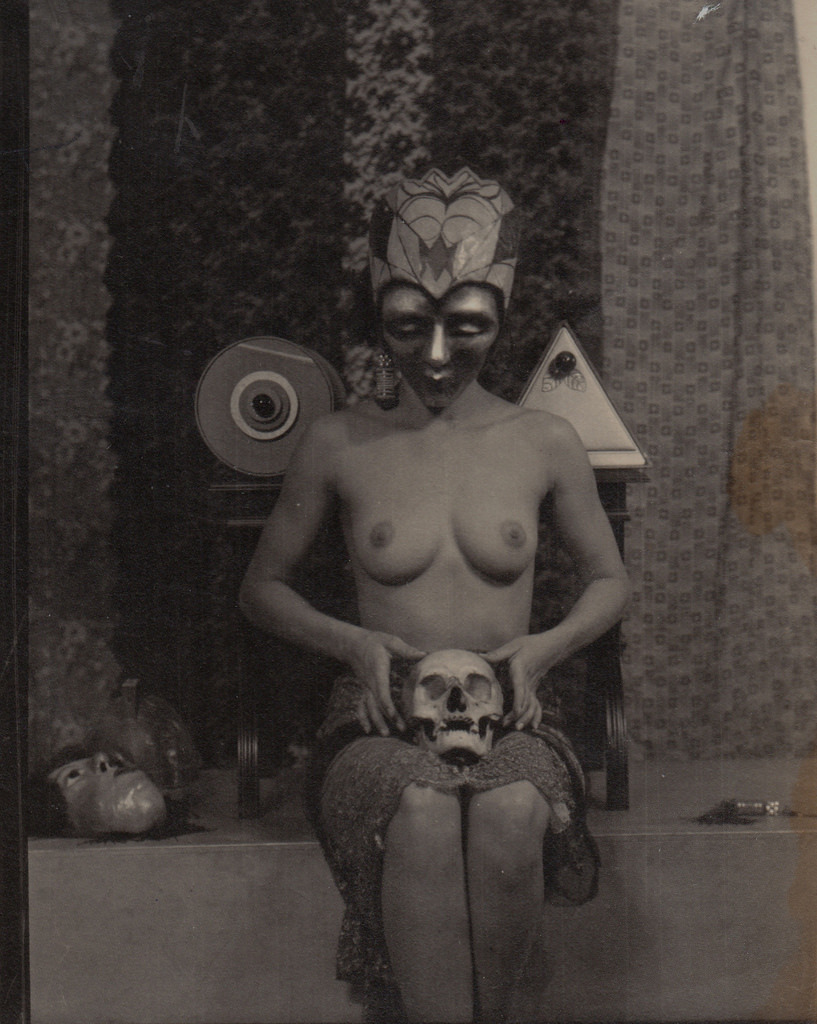

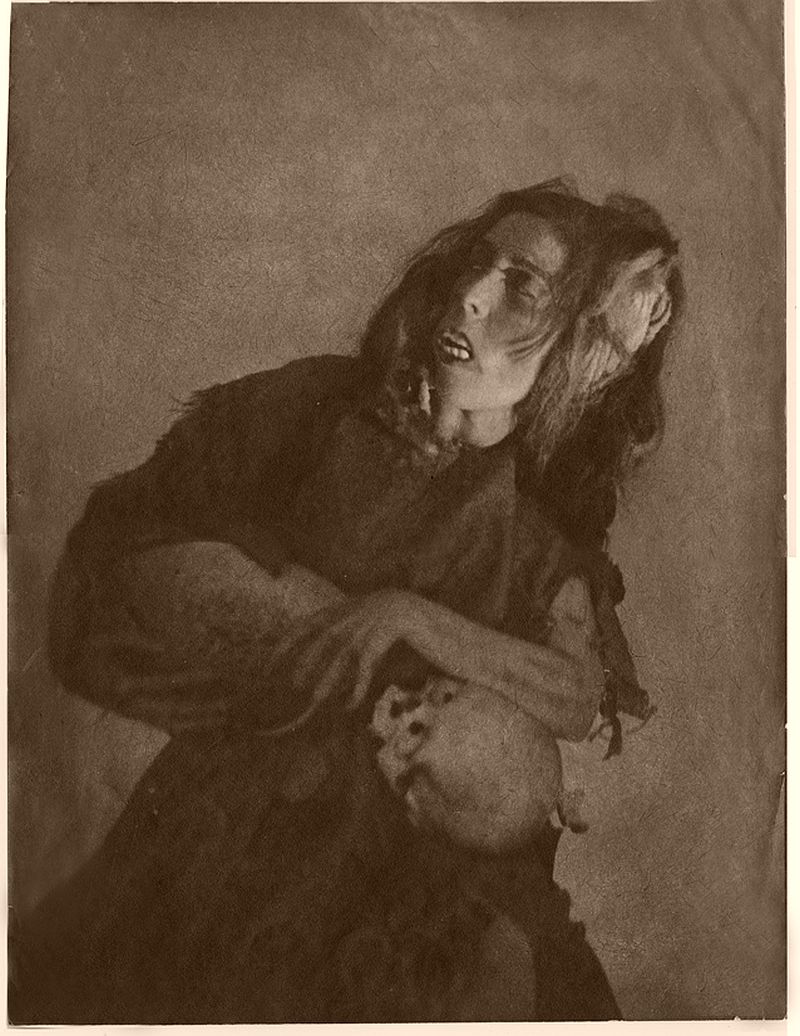

William Mortensen : Myrdith Monaghan Preparing for the Sabbot c. 1926

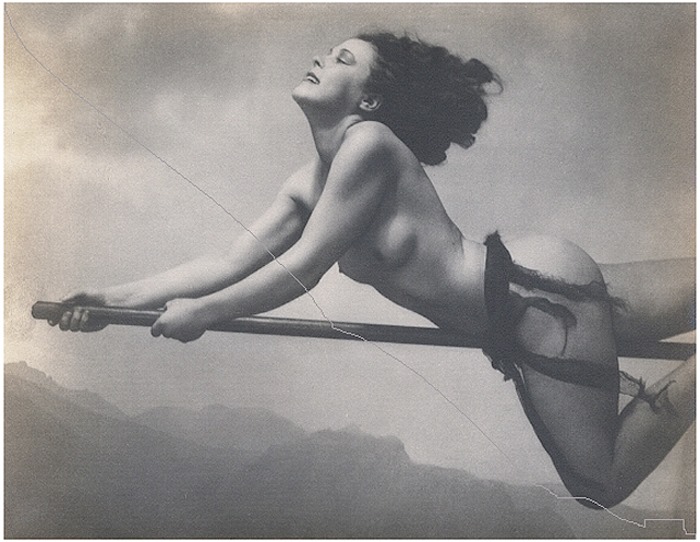

William Mortensen, “Myrdith on Broom”.c, 1930

So much or the rumours, then. Mortensen did marry – first to Courtney Crawford, a librarian, and then in 1933 to Myrdith Monaghan, an actress who appeared in many of his photographs. How many times she posed for her husband , often nude, we cannot be certain because Mortensen destroyed thousands more his early prints, “in a self-critical frenzy,” he wrote.

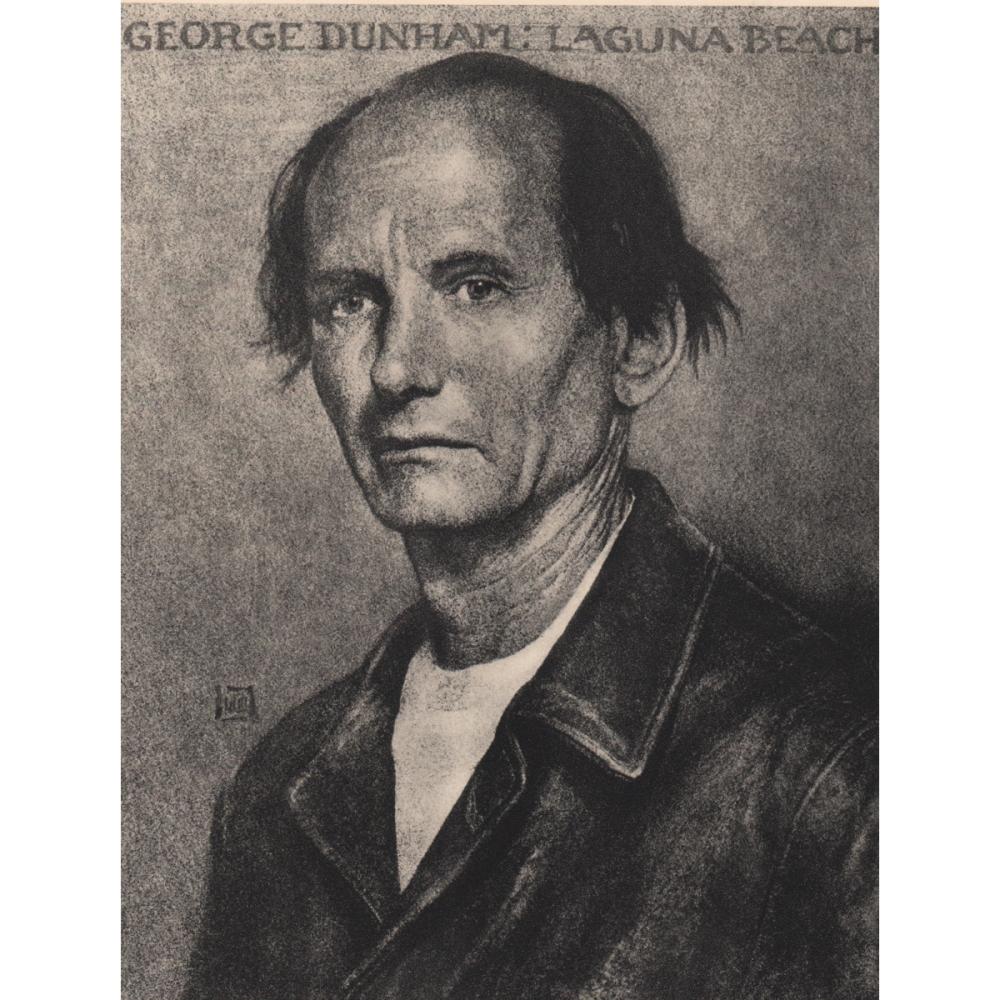

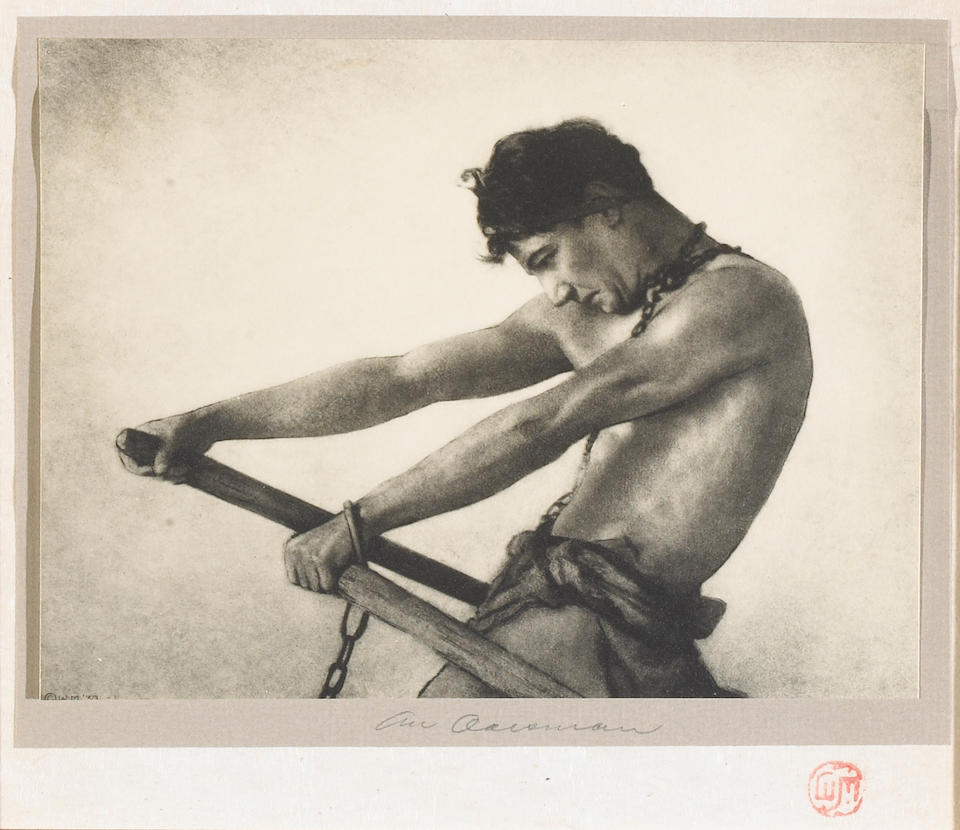

George Dunham

As well as marrying Myrdith in 1933, it was the year when Mortensen met George Dunham who became a friend and model. The pair began a writing partnership which didn’t end until 1960 with an incomplete manuscript titled Composition.

The 32-year collaboration produced 9 books in multiple editions and printings, 4 pamphlets, and over 100 articles in magazines and newspapers.

As for his intriguing, nightmarish photographs, Mortensen’s work was not all that popular, and despised by some. When he displayed his pictures in the window of his studio on Hollywood Boulevard, he “anxiously scanned the faces of passers-by for reactions,” he added, but no one paid attention. Maybe he was unable to post his nudes, as is most likely in the days of when art could be labelled an obscenity in the eyes of censorious lawmakers. Stick a nude on the wall and though you might not mean to stop to examine the work, biology takes over.

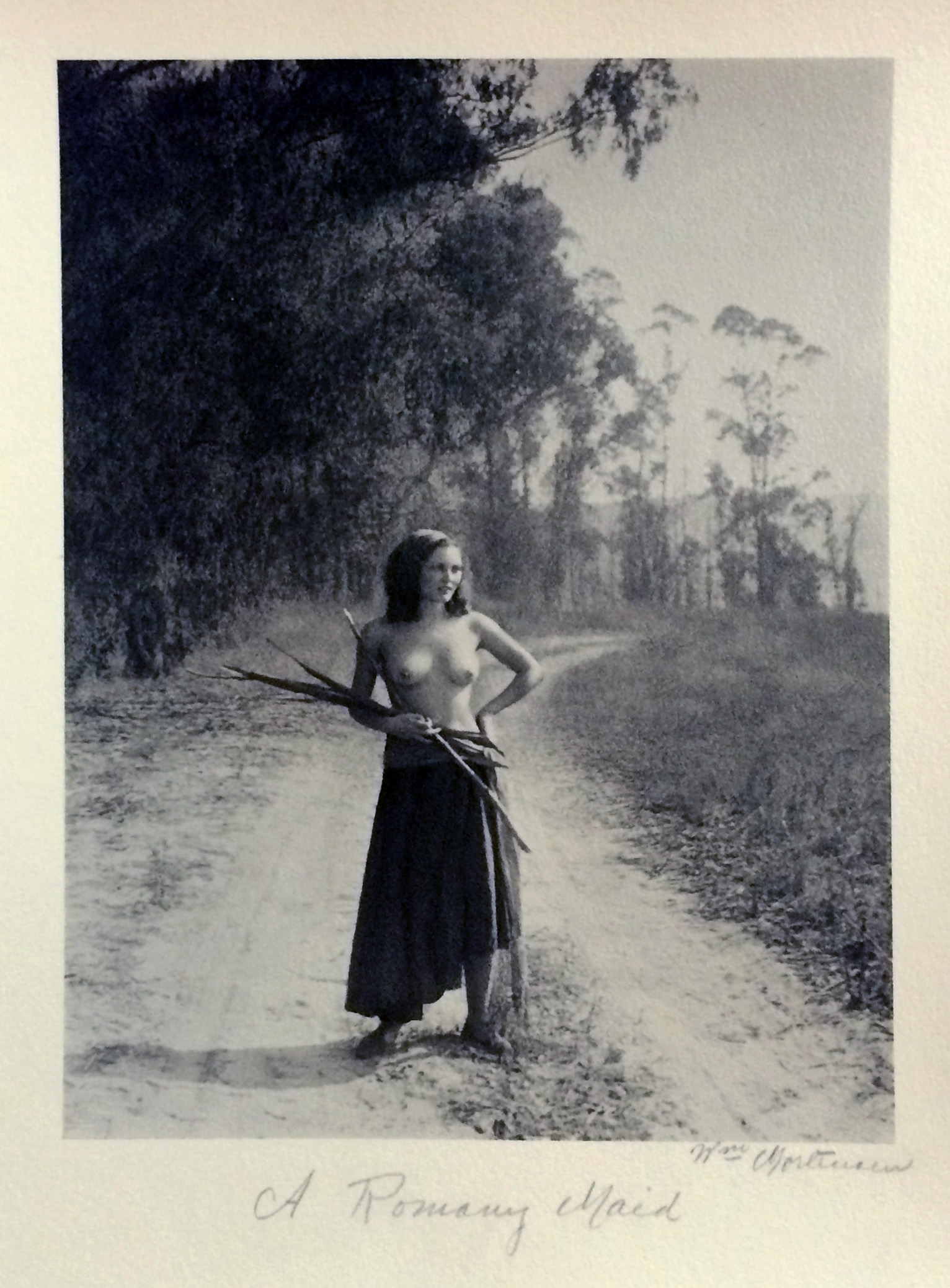

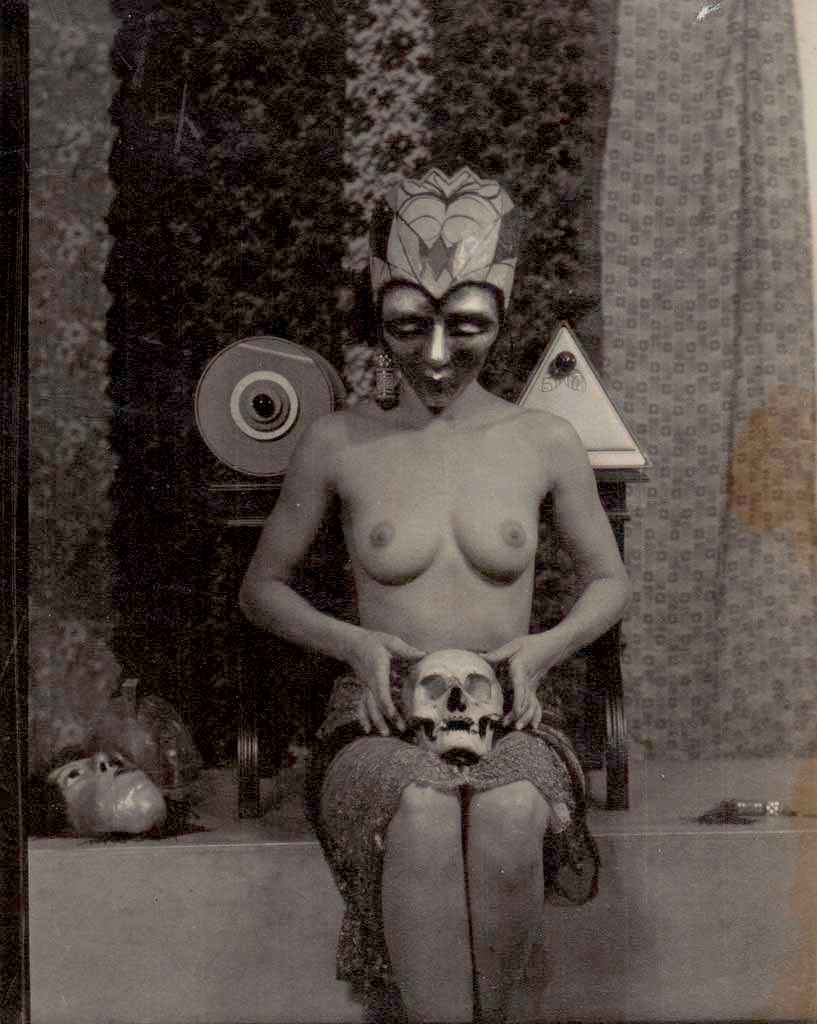

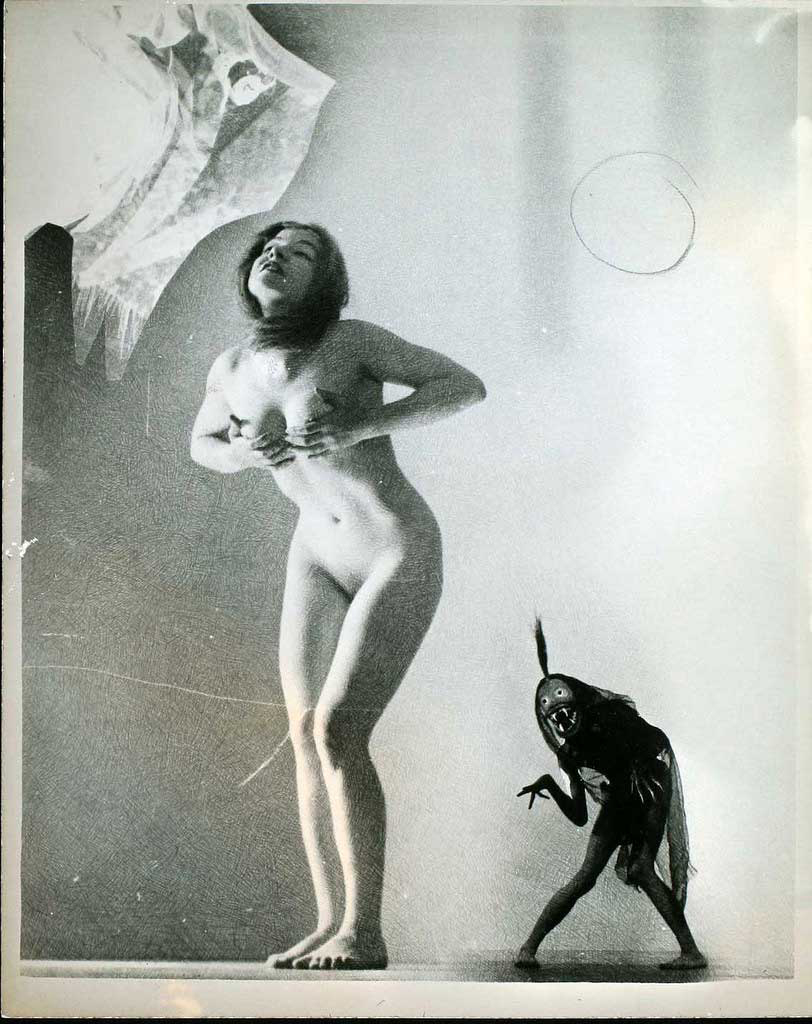

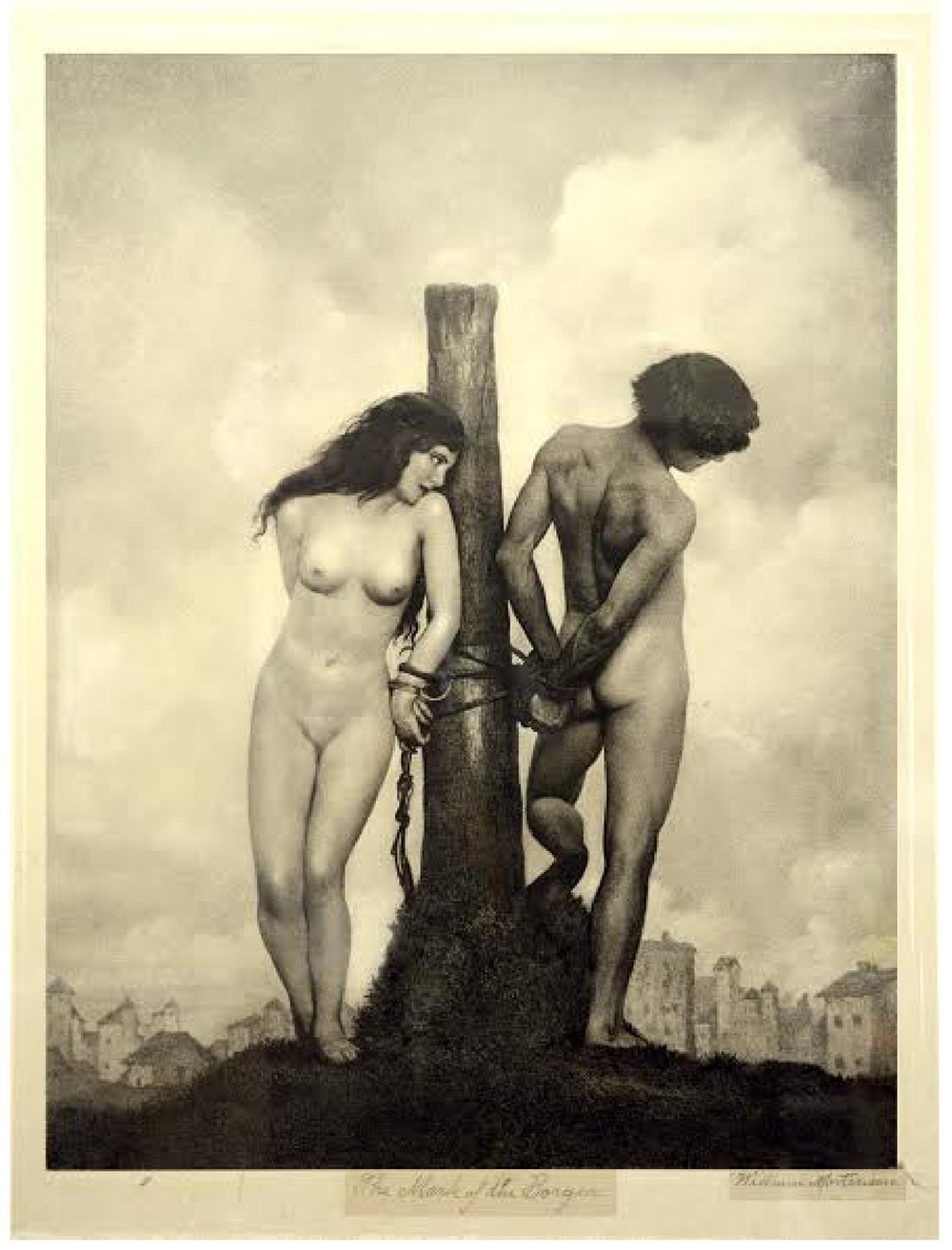

Another reason they didn’t much like his work was maybe down to Mortensen’s championing of pictorialism, a controversial element within photography that says it’s ok to retouch pictures and negatives with scratches, pens, chemical washes, pumice and traditional printmaking techniques, such as bromoiling. The end result is no snapshot or truthful representation of what the photographer saw, rather a theatrical vision, a scene carefully designed and constructed.

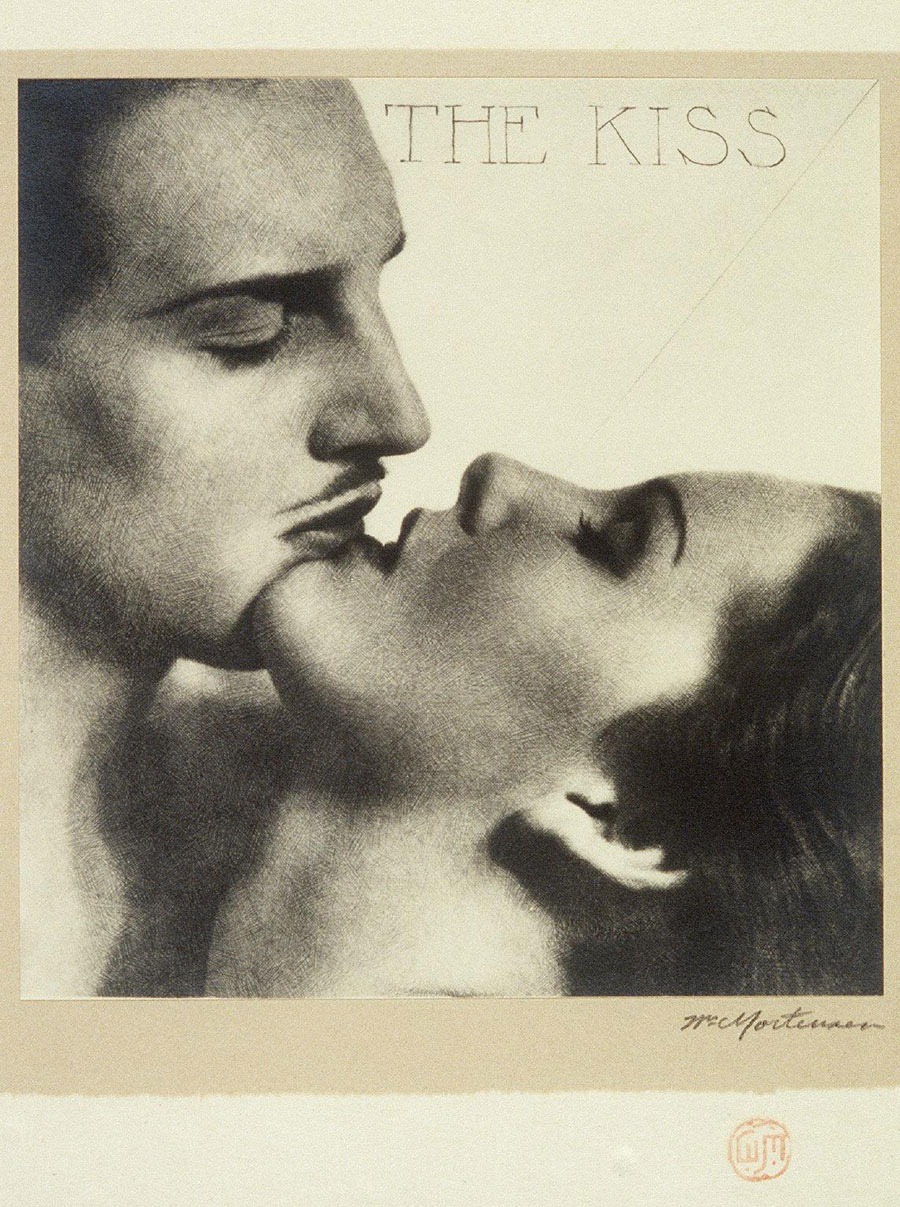

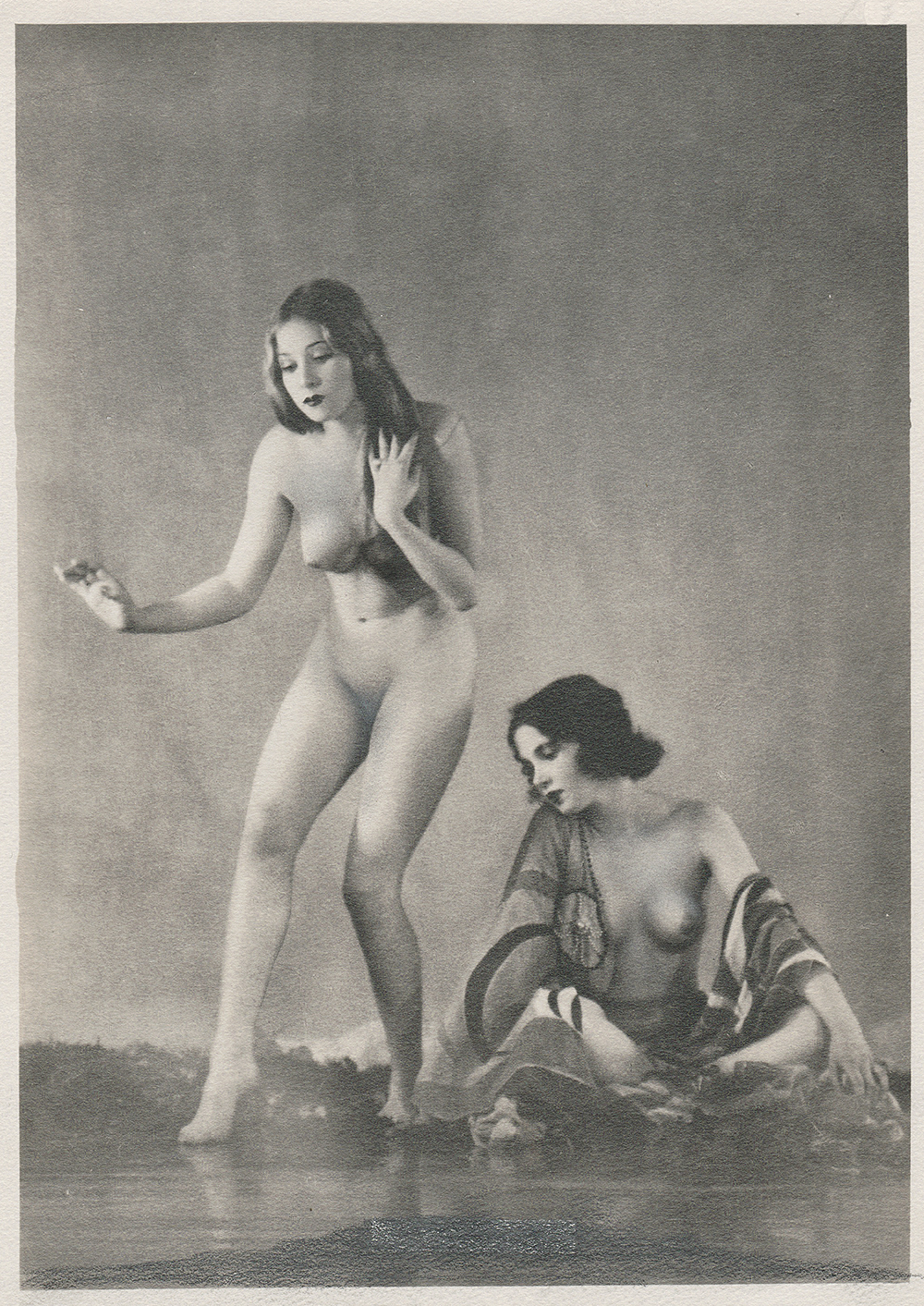

William Mortensen (American, 1897-1965) – The Kiss, c. 1930

Things improved for Mortensen. Working in Hollywood, he photographed many of the leading stars of his day: Rudolph Valentino, Lon Chaney, Fay Wray, Jean Harlow, Clara Bow and Peter Lorre all sat for him. His work was published in Vanity Fair, he had a weekly photography column in the Los Angeles Times, and he wrote a series of bestselling instructional books.

Mortensen was introduced to Hollywood director Cecil B DeMille, with whom he went on to work with as a set decorator, costumier and set photographer. DeMille published a monograph of Mortensen’s photographs from the set of The King of Kings.

Mortensen also made batik, costume jewellery and papiermâché masks. He produced a number of tribal masks for the Tod Browning movie West of Zanzibar, which starred Lon Chaney as a paraplegic magician living in an African village who takes to dressing as a god to maintain control over the tribe.

And he opened the Mortensen School of Photography at Laguna Beach. you can find a great collection of his work at the Laguna Beach Museum.

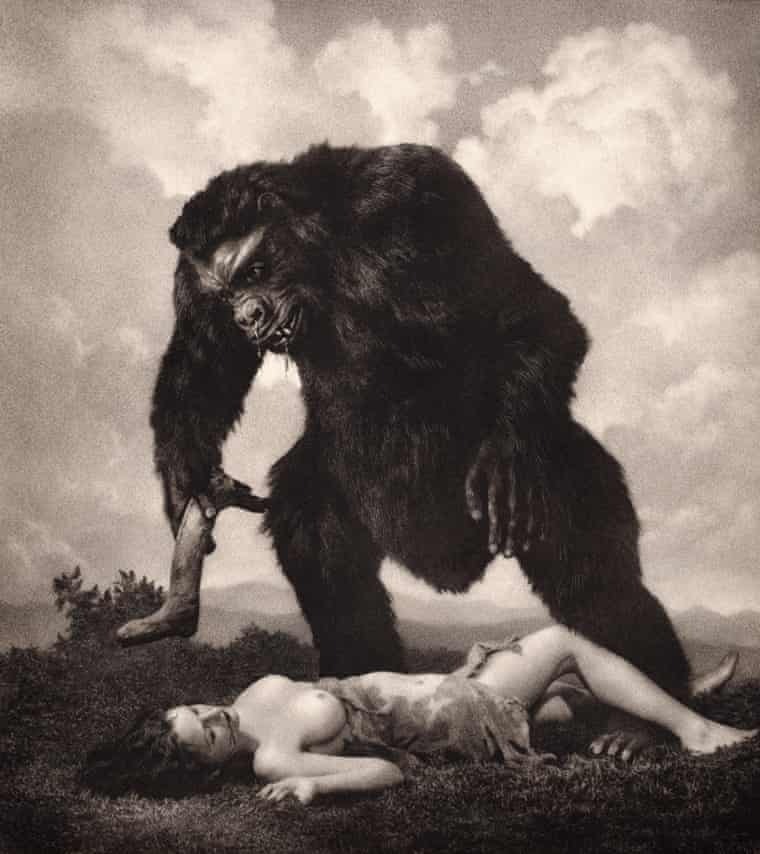

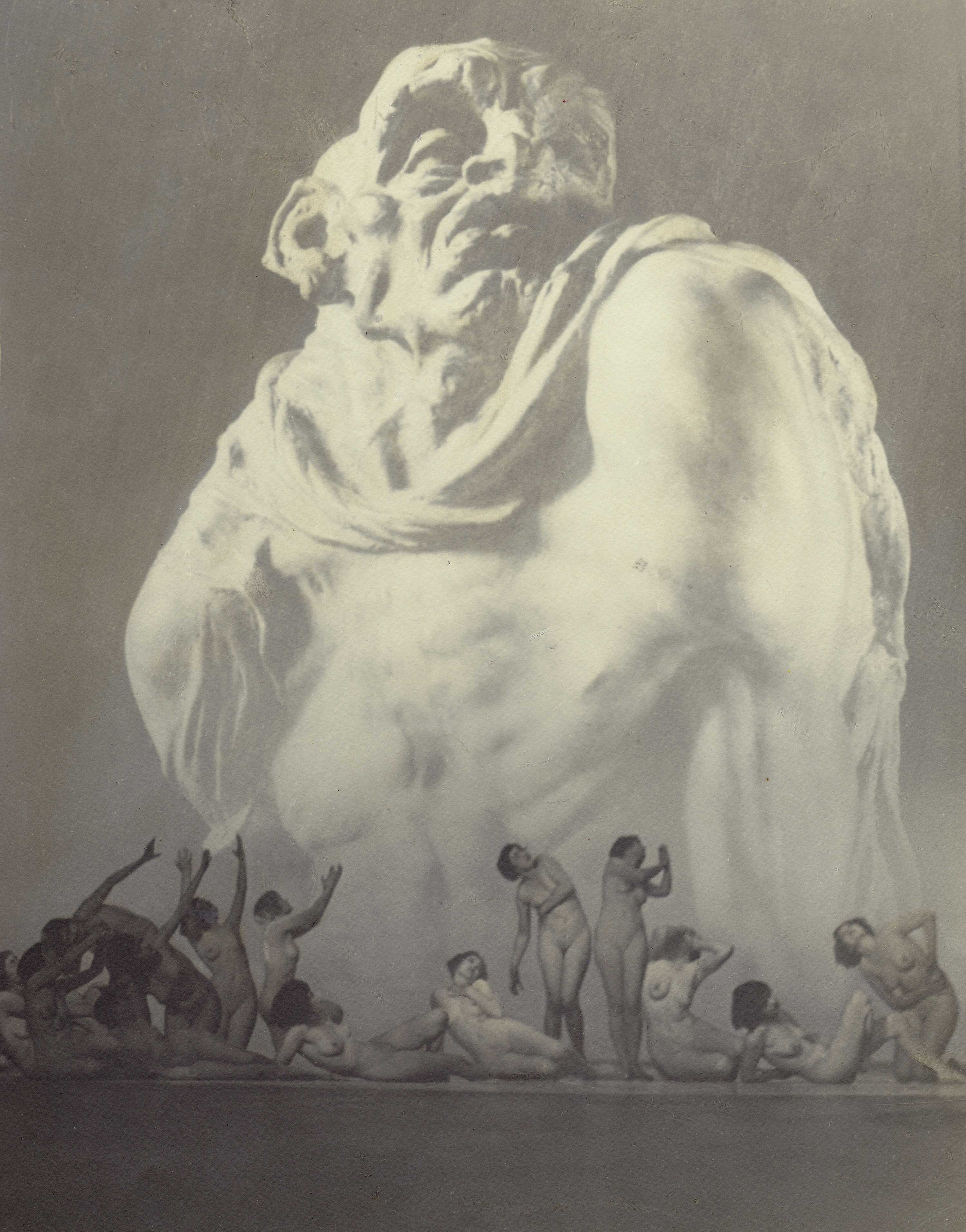

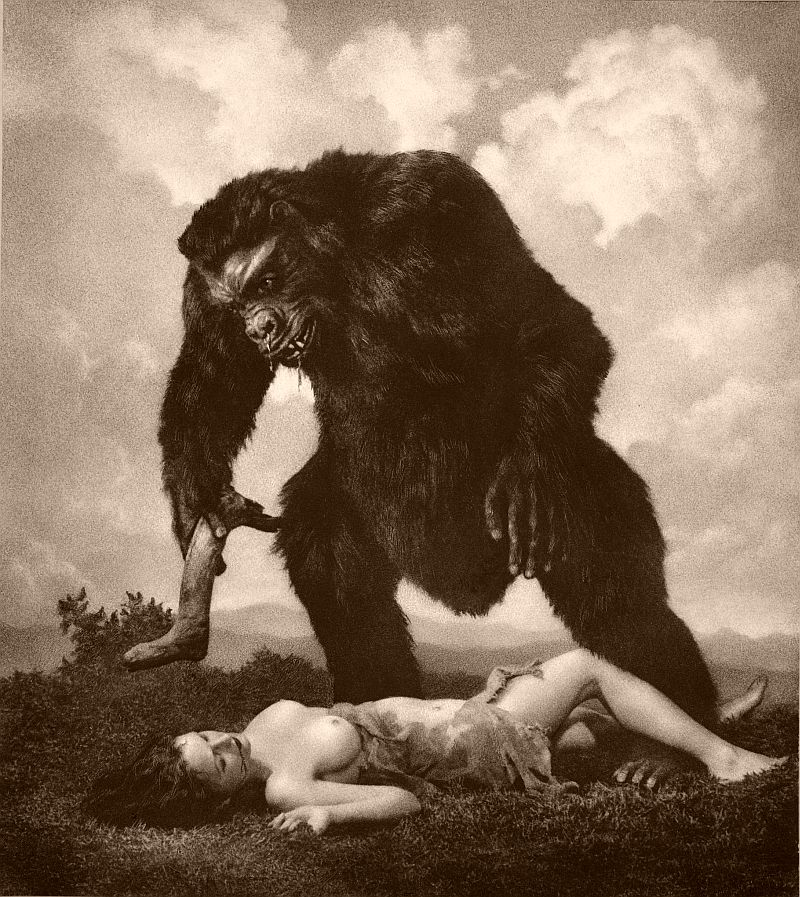

His viscerally manipulated photography often touched on themes of the occult, magic, witchcraft, sex, violence and horror. His work was in the context of the Universal monster movies that reigned supreme in the late 1920s and 30s, and the dark, nightmarish German expressionist style that inspired them. As Chris Campion writes, ‘L’Amour, one of Mortensen’s most iconic images (above), features a semi-naked woman lying on the ground, possibly dead, as a monstrous ape leers over her with a club, clearly a reference to King Kong, which had been released two years earlier in 1933. That bare-breasted woman on the ground could be Fay Wray, who played Kong’s love interest in the famous movie.

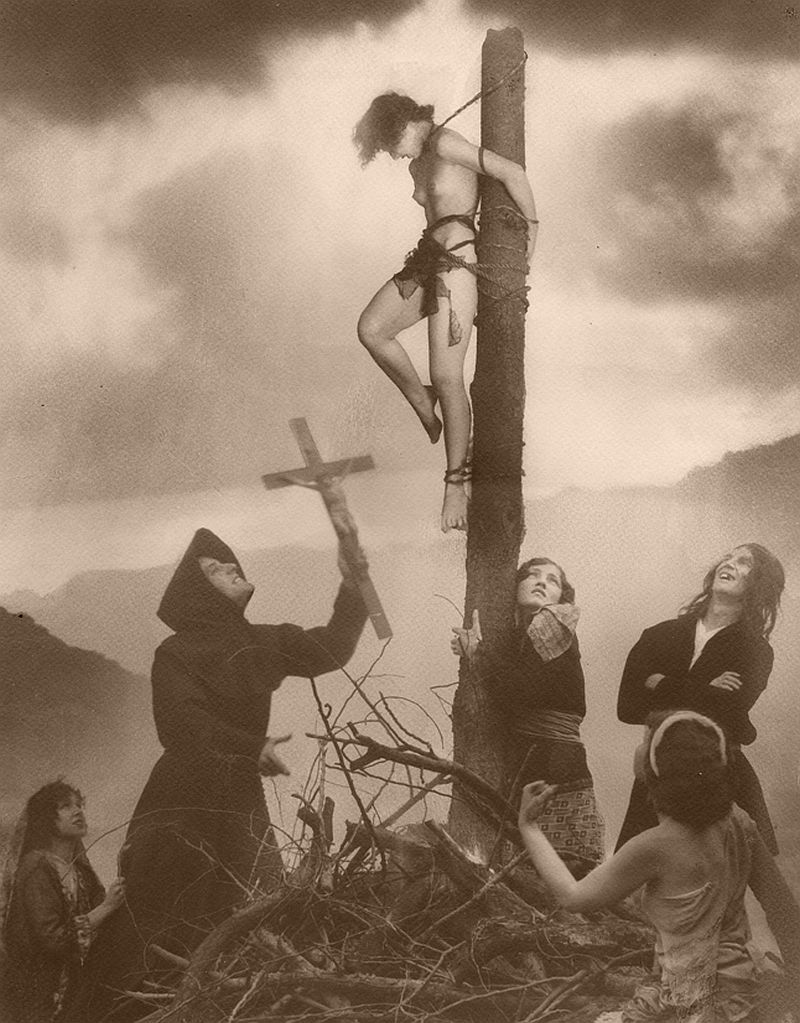

And there were the images of torture and death. Before war photography and televised images of human depravity became commonplace, he created The Glory of War (1927), depicting a woman lying among the destruction, a crucifix to her naked breast (above).

Those who wanted photography to be seen as a serious topic of modernist study hated it. American photographer Ansel Adams, known for his landscape photographs of the American West. referred to Mortensen as the “Devil”, and “the anti-Christ.” High praise, indeed. When photographer Edward Weston told Adams of his excitement at photographing a “fresh corpse”, Adams replied: “My only regret is that the identity of said corpse is not our Laguna Beach colleague.”

In “Venus and Vulcan”, a series of 1934 Camera Craft magazine essays, Mortensen defended Pictorialism against criticism from California’s f.64 school of photography, co-created by the aforesaid Adams, and other “straight shooters” who pitched themselves as custodians of what is right and proper in art, writes Carey Loren at 50Watts. Mortensen observed:

Photography, like any other art, is a form of communication. The artist is not blowing bubbles for his own gratification, but is speaking a language, is telling somebody something. Three corollaries are derived from this proposition.

a. As a language, art fails unless it is clear and unequivocal in saying what it means.

b. Ideas may be communicated, not things.

c. Art expresses itself, as all languages do, in terms of symbols

In his book Monsters & Madonnas, Mortensen adds: “Through technique, the mechanical is bent to the needs of the creative. In this sense of the word, most photographers completely lack technique. Many have acquired mechanical skill, some have creative ability; but few have managed to bridge the gap between the two.”

Myrdith Monaghan by William Mortensen, c. 1930

More at Stephen Romano Gallery in Brooklyn will have a draw for an original William H. Mortensen.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.