Maggs has issued a scratch catalogue of William Burroughs’ photographs of London 1972 – 1974. These are hand-made prints produced a few years ago from the original negatives and are conservation-framed and glazed.

Below are some more pages from the catalogue plus an insight into Burroughs’ time in London’s Mayfair area, when he frequented ‘Dilly Boys in the local public urinals, almost killed another writer – one who would start a ‘religion’ – and tormented the owners of the city’s first coffee shop until they finally gave in and closed the place.

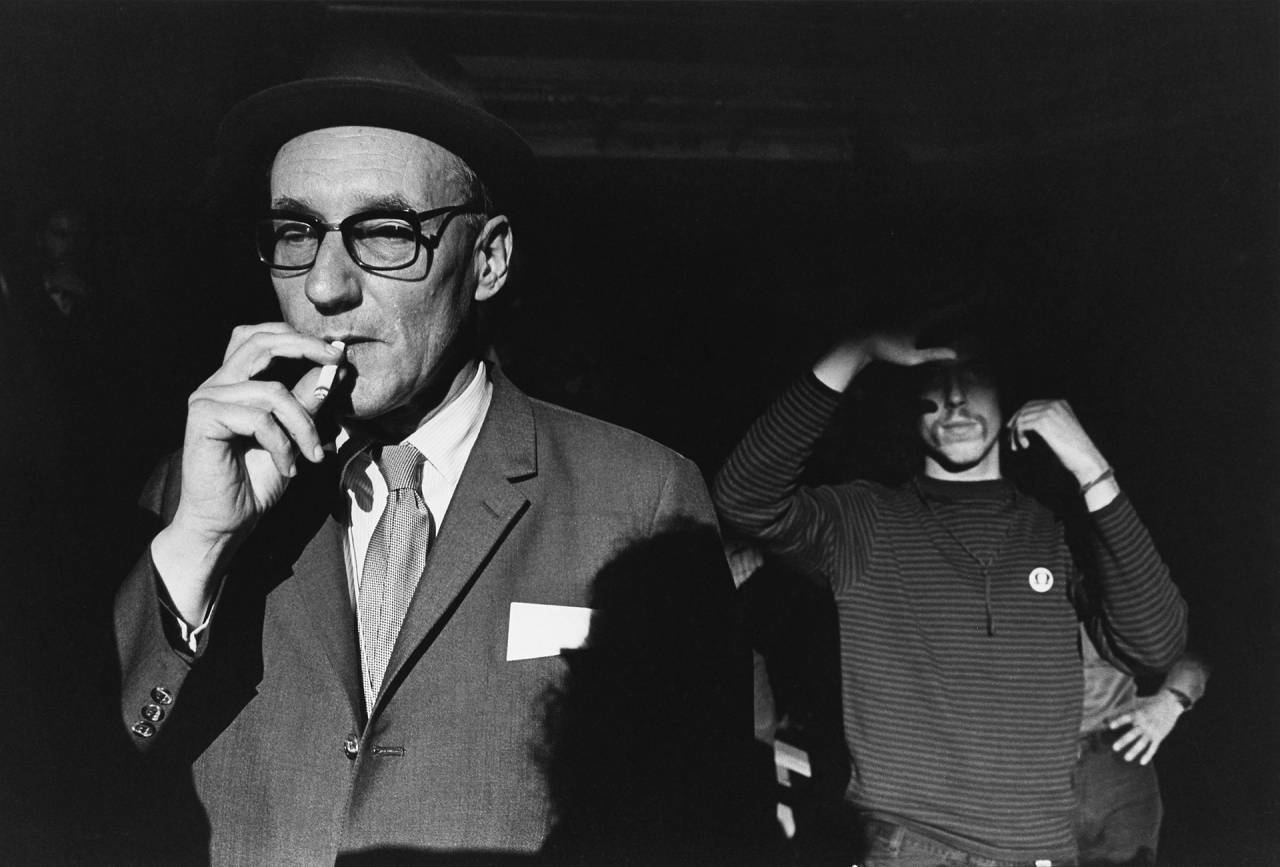

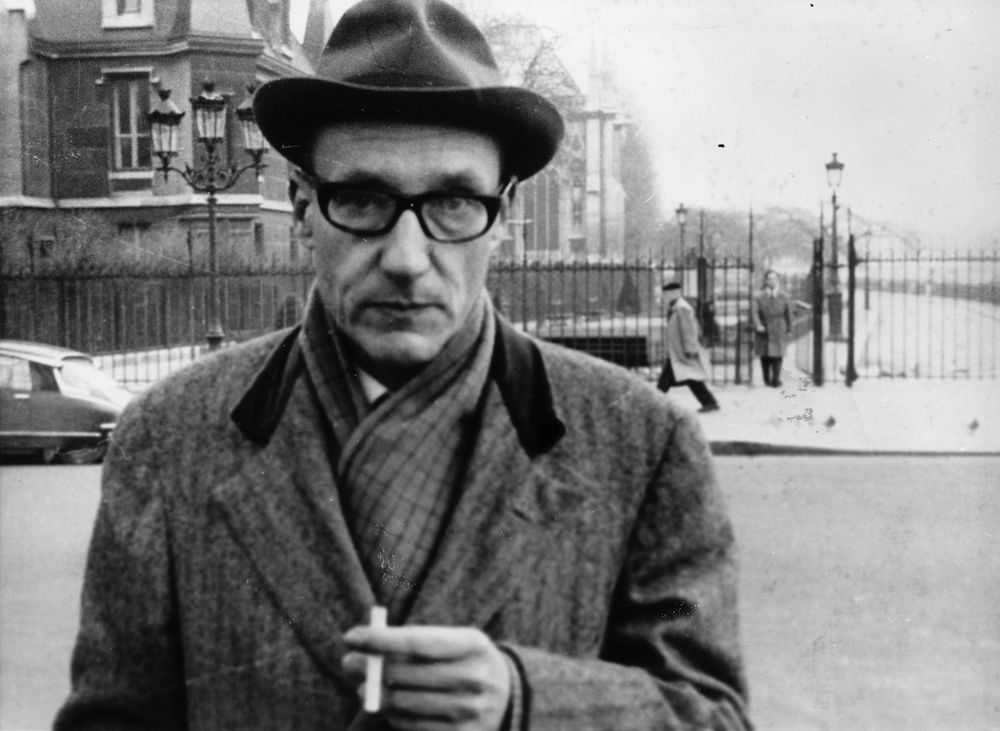

William S Burroughs lived at 8 Duke Street (1967-1974), writing during his time there The Ticket That Exploded, The Wild Boys and The Job. The author JG Ballard recalled meeting him at the address:

I first met him in the early ’60s in London. I visited him in his flat in Piccadilly Circus. I’m not sure that he got up to a great deal of writing there. He didn’t seem that happy.

This was in a street called Duke Street, literally about 100 yards from Piccadilly Circus. And, of course, this was of interest to him because that’s where all the boys used to congregate, in the lavatory of the big Piccadilly Circus Underground station. They had completely taken it over. It was quite a shock for a heterosexual like myself to accidentally stray into this lavatory and to find oneself in what seemed to be a kind of oriental male brothel. He obviously found that absolutely fascinating…

And by way of a tasty side order:

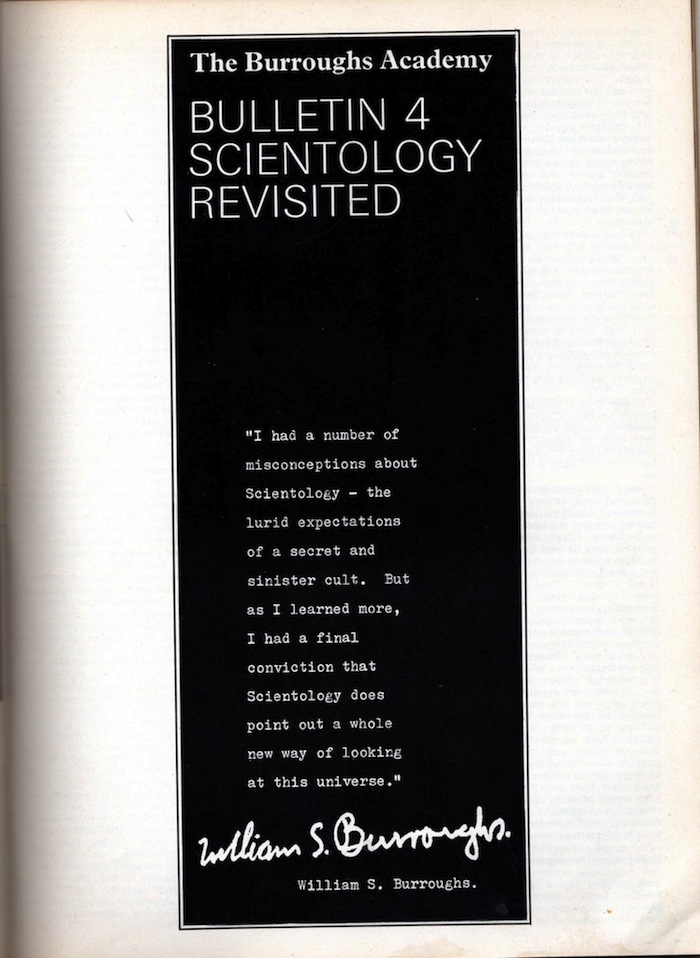

It was from here that he joined the scientology cult, helping to find new members. On becoming disillusioned he said he used to fire an air pistol at photo’s of it’s founder L Ron Hubbard at his flat here.

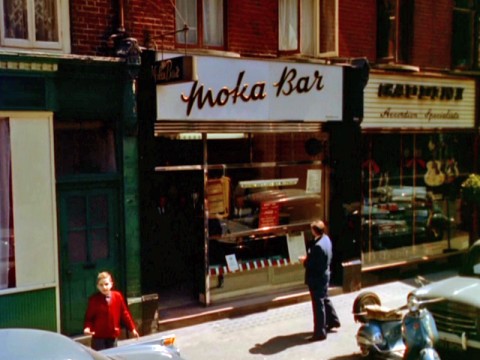

The Moka Bar Operation:

Gina Lollobrigida opened the Moka Bar at 29 Frith Street in 1953. The café provided London with its first Gaggia machine. Very soon other coffee shops opened and Frith Street was dubbed Froth Street.

Peter Watts explains what happened when Burroughs happened upon the scene:

Burroughs at this time was getting sick of London – sick of the licensing laws, sick of the crap food and small drinks, sick of the weather, the terrible service and sexual hypocrisy. He was also sick of the Moka, which he believed responsible for an ‘outrageous and unprovoked discourtesy and poisonous cheesecake’…

On August 3, 1972, Burroughs turned his attention to the Moka. He would stand outside every day taking photos and making recordings by tape, and then return the next day to play the previous days recordings. Burroughs was convinced he was winning. ‘They are seething in there,’ he said. ‘I have them and they know it.’

On October 30, 1972, the Moka Bar closed.

Ted Morgan, in Burroughs biography Literary Outlaw, says the writer was upset “at what he was paying for his hole-in-the-wall apartment with a closet for a kitchen… Burroughs began to feel that he was in enemy territory.” He’d target his fury on the Moka Bar.

Burroughs’ talks about his Moka attack in ‘Playback From Eden To Watergate’ (via The Job: Interviews with William S. Burroughs):

Here is a sample operation carried out against the Moka Bar at 29 Frith Street, London, W.1, beginning on August 3, 1972. Reverse Thursday. Reason for operation was outrageous and unprovoked discourtesy and poisonous cheesecake. Now to close in on the Moka Bar. Record. Take pictures. Stand around outside. Let them see me. They are seething around in there. The horrible old proprietor, his frizzy-haired wife and slack-jawed son, the snarling counterman. I have them and they know it.

“You boys have a rep for making trouble. Well, come on out and make some. Pull a camera-breaking act, and I’ll call a bobby. I got a right to do what I like in the public street.”

If it came to that, I would explain to the policeman that I was taking street. recordings and making a documentary, of Soho. This was after all London’s first espresso bar, was it not? I was doing them a favour. They couldn’t say what both of us knew without being ridiculous.

“He’s not making any documentary. He’s trying to blow up the coffee machine, start a fire in the kitchen, start fights in here, get us a citation from the Board of Health.”

Yes, I had them and they knew it. I looked in at the old prop. and smiled, as if he would like what I was doing. Playback would come later with more pictures. I took my time and strolled over to the Brewer Street Market, where I recorded a three-card Monte game. Now you see it, now you don’t.

Playback was carried out a number of times with more pictures. Their business fell off. They kept shorter and shorter hours. October 30, 1972, the Moka Bar closed. The location was taken over by the Queen’s Snack Bar.

How to apply the three-tape-recorder analogy to this simple operation. Tape recorder one is the Moka Bar itself in its pristine condition. Tape recorder two is my recording of the Moka Bar vicinity. These recordings are access. Tape recorder two in the Garden of Eden was Eve made from. So a recording made from the Moka Bar is a piece of the Moka Bar. The recording once made, this piece becomes autonomous and out of their control. Tape recorder three is playback. Adam experiences shame when his disgraceful behaviour is played back to him by tape recorder three, which is God.

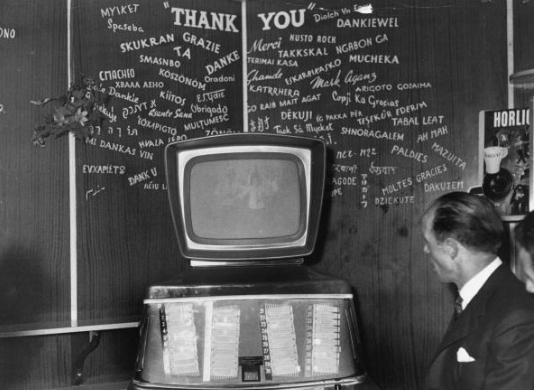

Cine juke box, known as the ‘Cinebox’ installed at the Moka Bar, Frith Street, London, c 1962. The image is a juke box that has a television screen above it that shows a video while the chosen song is playing. ‘It’s the latest coffee bar entertainment and

Josh Jones notes:

The theory made perfect sense to Burroughs, who believed in a Magical Universe ruled by occult forces and who experimented heavily with Scientology, Crowley-an Magick, and the orgone energy of Wilhelm Reich. The attack on the Moka worked, or at least Burroughs believed it did.

Heathcote Williams has more on Burroughs in London. On assignment for literary magazine Transatlantic Review in 1963, he met Burroughs for the first time.

Bill had come to England from Tangier principally to take a heroin cure which he had set great store by. The cure had been devised by a Dr John Yerbury Dent of the BRITISH JOURNAL OF ADDICTION and consisted of apomorphine which was apparently morphine boiled in hydrochloric acid. ‘It works as a total body emetic,’ Bill explained, ‘if you even have even the remotest whiff of heroin your whole body throws up.’

He insisted that Dr. Dent’s formula was working although I couldn’t help noticing that he seemed keen on a cough mixture called Breathe-Eezee which contained morphine, and I’m not sure that he wasn’t also taking Collis Brown, a popular cure-all, which in those days used to have morphine in it as well….

“Apomorphine,” Burroughs wrote later, “acts on the back brain to normalise the bloodstream in such a way that the enzyme system of addiction is destroyed… At the time I took the apomorphine cure. I had no claims to call myself a writer and my creativity was limited to filling a hypodermic. The entire body of work on which my present reputation is based was produced after the apomorphine treatment, and would never have been produced if I had not taken the cure and stayed off junk.”

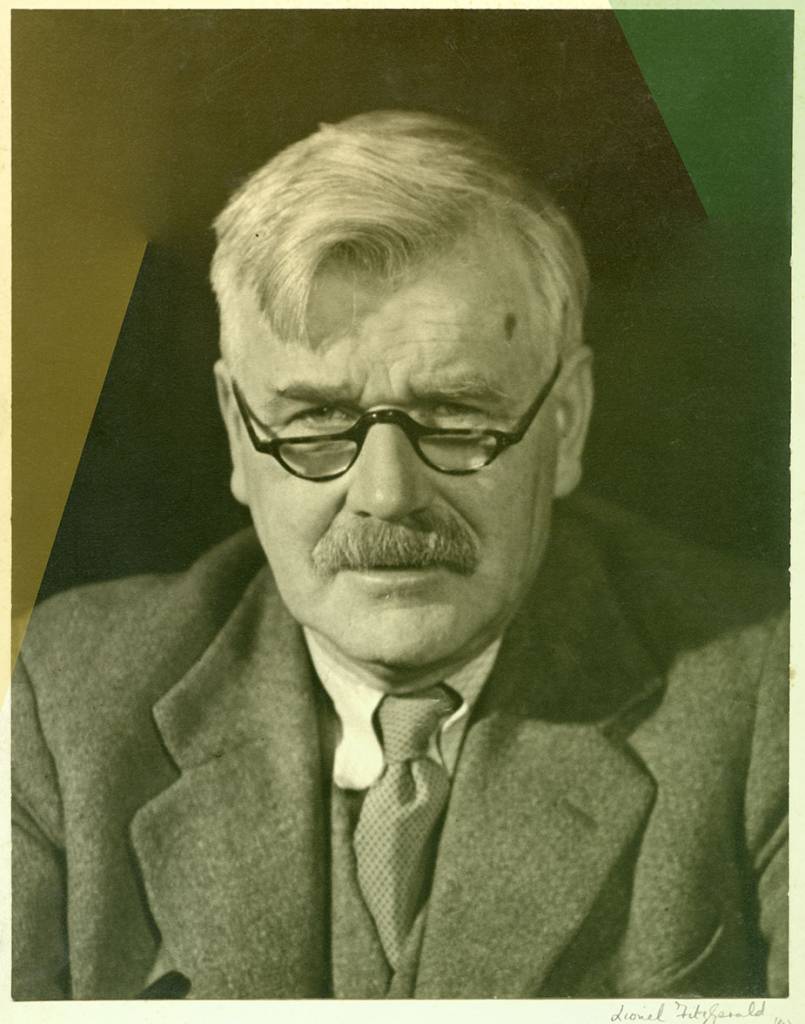

Dr John Yerbury Dent Via

Amory continues:

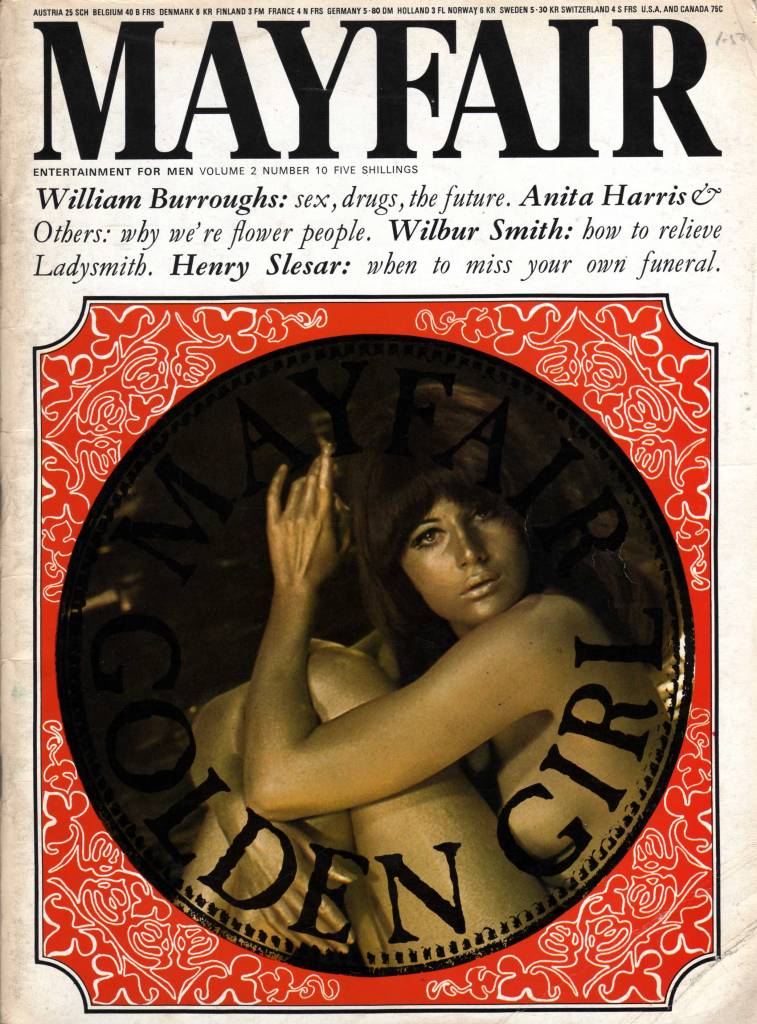

I think Bill found London bleak. He once said with cold sarcasm at UK Customs on being asked for his reason for visiting Britain: ‘Number one: the food. Number two: the weather.’ And he remarked scathingly to a friend, Martin Wilkinson, ‘You think your country’s problems are going to be solved by your moth-eaten Queen?’… nonetheless, despite a seeming indifference to the UK he stayed on in London for quite some while after Dr. Dent’s cure primarily, I think, because he was getting published here: first of all quite humbly in the hand-duplicated pages of Jeff Nuttall’s MY OWN MAG; then, with some regularity, in the earliest issues of INTERNATIONAL TIMES; and in Mayfair magazine, a kind of English PLAYBOY, which ran a series of his articles exposing scientology.

“Interview” and “The Future of Sex and Drugs”. (The Burroughs Academy Bulletin 1) Mayfair Vol. 2, No. 10, pp 11-15. London: October 1967. Via

In 1965, William S. Burroughs was interviewed by Conrad Knickerbocker in The Paris Review. He discussed his treatment:

I was living in Tangier in 1957, and I had spent a month in a tiny room in the Casbah staring at the toe of my foot. The room had filled up with empty Eukodol cartons; I suddenly realized I was not doing anything. I was dying. I was just apt to be finished. So I flew to London and turned myself over to Dr. John Yerbury Dent for treatment. I’d heard of his success with the apomorphine treatment. Apomorphine is simply morphine boiled in hydrochloric acid; it’s nonaddictive. What the apomorphine did was to regulate my metabolism. It’s a metabolic regulator. It cured me physiologically. I’d already taken the cure once at Lexington, and although I was off drugs when I got out, there was a physiological residue. Apomorphine eliminated that. I’ve been trying to get people in this country interested in it, but without much luck. The vast majority—social workers, doctors—have the cop’s mentality toward addiction. A probation officer in California wrote me recently to inquire about the apomorphine treatment. I’ll answer him at length. I always answer letters like that.

Amory adds a macabre twist to the interview. Burroughs is staying in an Earl’s Court Hotel. The topic of speaking to the Paris Review crops up.

‘Have you seen the mortality rate amongst PARIS REVIEW interviewees?’ and with that he [Burroughs] produced a copy of the current issue and, not entirely tongue in cheek, read out a long list of the PARIS REVIEW fatalities from the masthead: ‘See that? Ezra Pound? Dead. Eliot? Dead. Hemingway? Dead. Faulkner? Dead….’ And so on. He produced an eerily long list by way of confirming his apprehensions.

But he agreed to the interview. Did he survive it?

‘Oh yes, I did,’ he said, then added with a lugubrious chuckle, ‘but the interviewer didn’t. The interviewer was called Conrad Knickerbocker and he recently threw himself from a block of flats in St. Louis.’ He accompanied the words with an odd pursing twitch of the lips that I often noticed. It was a kind of mild tic which seemed to indicate a certain pleasure in that otherwise immobile and unsmiling face – in this case it belied a voluntary or involuntary appreciation of the macabre.

Amory picks up the story of Burroughs’ life in Mayfair.

Burroughs then moved to Duke Street in St James’s, Piccadilly, around the corner from Fortnum and Mason, the royal grocers. His collaborator, Brion Gysin, was hoping that their dream machine was going to make their fortune as a drug-free psychedelic that could be marketed by some big corporation. They installed one in Fortnum and Mason for visitors to sample its hypnotic flickering. There were, unfortunately, no takers.

When I went round to Duke Street it often seemed that Burroughs attracted a coterie of characters very much like those whom he was satirising in his work. One fictional character of his, for example, whom he called the ‘Intolerable Kid’ – a nightmarish creature of total appetite – sprang to life in the form of Mikey Portman, an epicene, voracious youth with a large mouth who would consume anything within reach and quickly turn the whole of the Duke Street flat into his ashtray and needle depository.

Even though Burroughs had renounced drugs and was an expert analyst of the iniquities of the drug pyramid and its cruel chain of exploitation and metabolic enslavement, he seemed to hold an allure for junkies who were drawn to him like iron filings to a magnet. It was if he’d given their unfortunate predicament some glamour, or gravitas even, even though he himself was contemptuous in many ways of the stoned hedonism of Sixties culture. ‘Nothing worse,’ he’d groan disparagingly ‘than going into a room full of giggling tea heads.’

In 1974, Allen Ginsberg gained for Burroughs a contract to teach creative writing at the City College of New York. Burroughs left London and moved to the city.

Email Carl Williams at Maggs for copies of the catalogue, larger images and viewings.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.