“Long live the imagination! Because everything that exists once was an idea. Long live the will! For the act of wanting to change the world and make it freer”

– Wenzel Hablik

Wenzel Hablik called the painting of the skies you an see above Starry Sky, Attempt. The Czech artist recognised that his bright, hopeful vision of a cosmos bristling with life and luminosity might be flawed. But Hablik was an optimist, whose depictions of otherworldly temples, flying cities and crystal chasms was a utopian vision of his lifelong aim to “Speak out! Speak out! Delight in existence – in the universe – in being and perishing.”

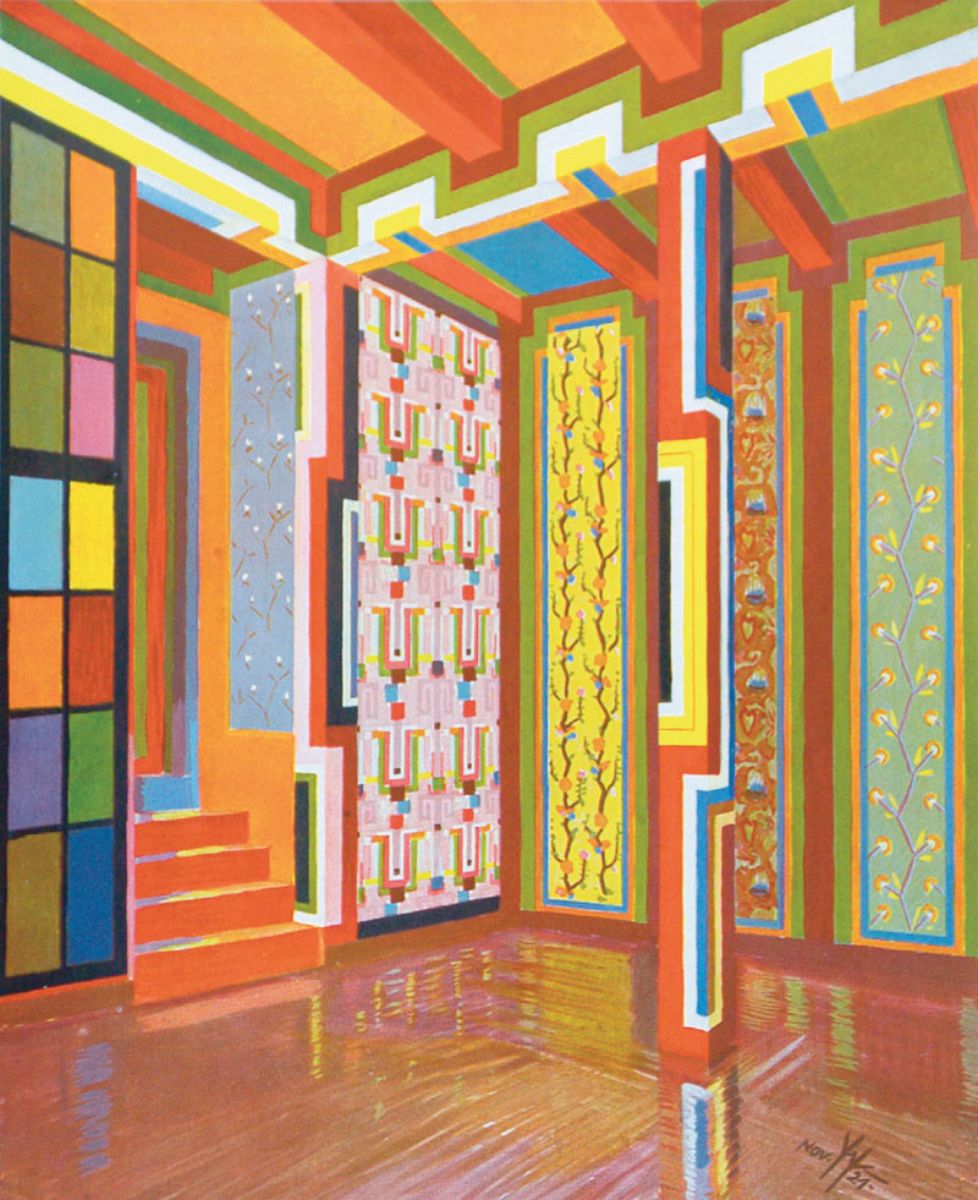

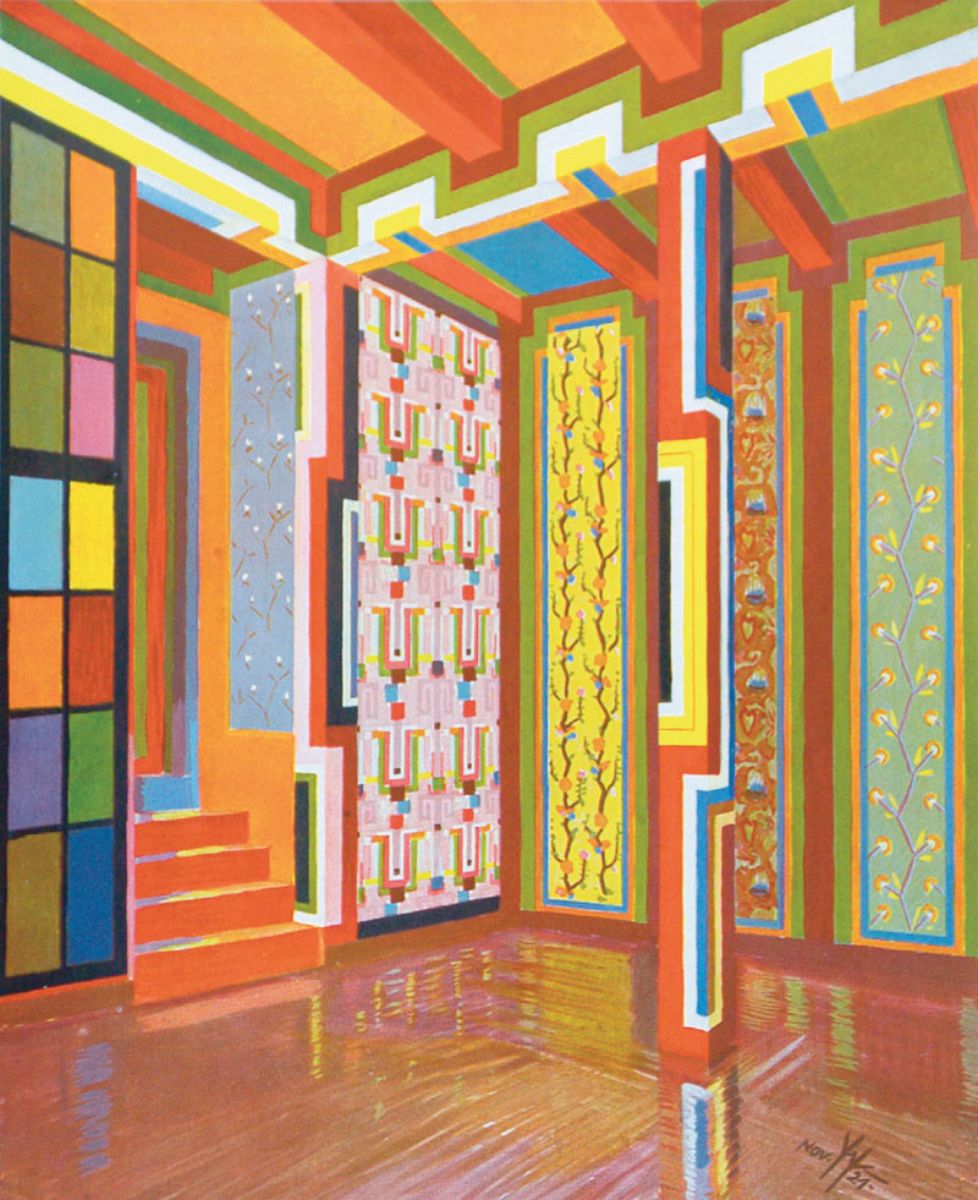

Exhibition Space Wallpapers is a Futurist and Art Nouveau artwork created by Wenzel Hablik in 1921. You can buy prints of his work in the shop.

Wenzel Hablik (1881–1934) was born in the Bohemian town of Brüx, Austria-Hungary (now Czech Republic). The world opened up to him when at age six he found a crystal. Peering into it he saw “magical castles and mountains”, themes that appeared in his art throughout his life. In those natural crystalline forms he saw the power of creative forces.

His fascination with forms of nature was fostered when at age eight he began work as a carpenter apprenticeship in his father’s shop. At age 12 he achieved the rank of master cabinetmaker. He went on to work as a porcelain painter, and a draftsman in an architect’s office. Between 1902 and 1905, he studied painting and heraldry at the Vienna Kunstgewerbeschule, followed by three years of studies at the Prague Academy of Arts. An individualist, in 1906 he made a solo ascent of Mont Blanc, Europe’s highest mountain.

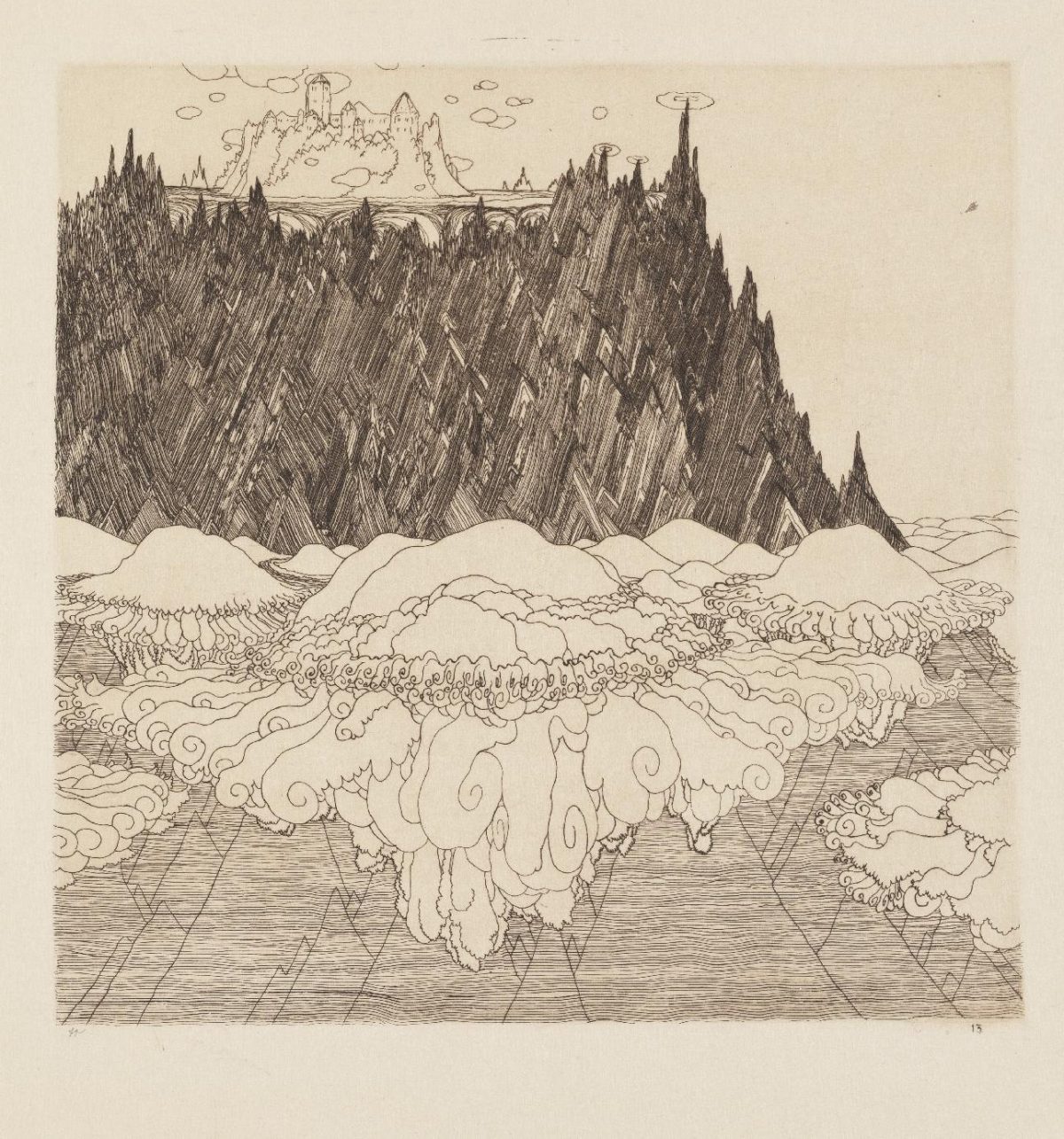

From the series of twenty etchings Creative Forces (Die Schaffenden Kräfte), 1909 – a journey through an imaginary universe of crystalline structures

Hablik’s first paintings, made in Prague between 1905 and 1907, were influenced by seeing Edvard Munch’s art and reading the works of German philosophers Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860), who characterised the phenomenal world as the product of a blind noumenal will and transcendental idealism, and Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 – 1900), whose ideas challenged the comfortable presuppositions and assumptions of religion, morality and science.

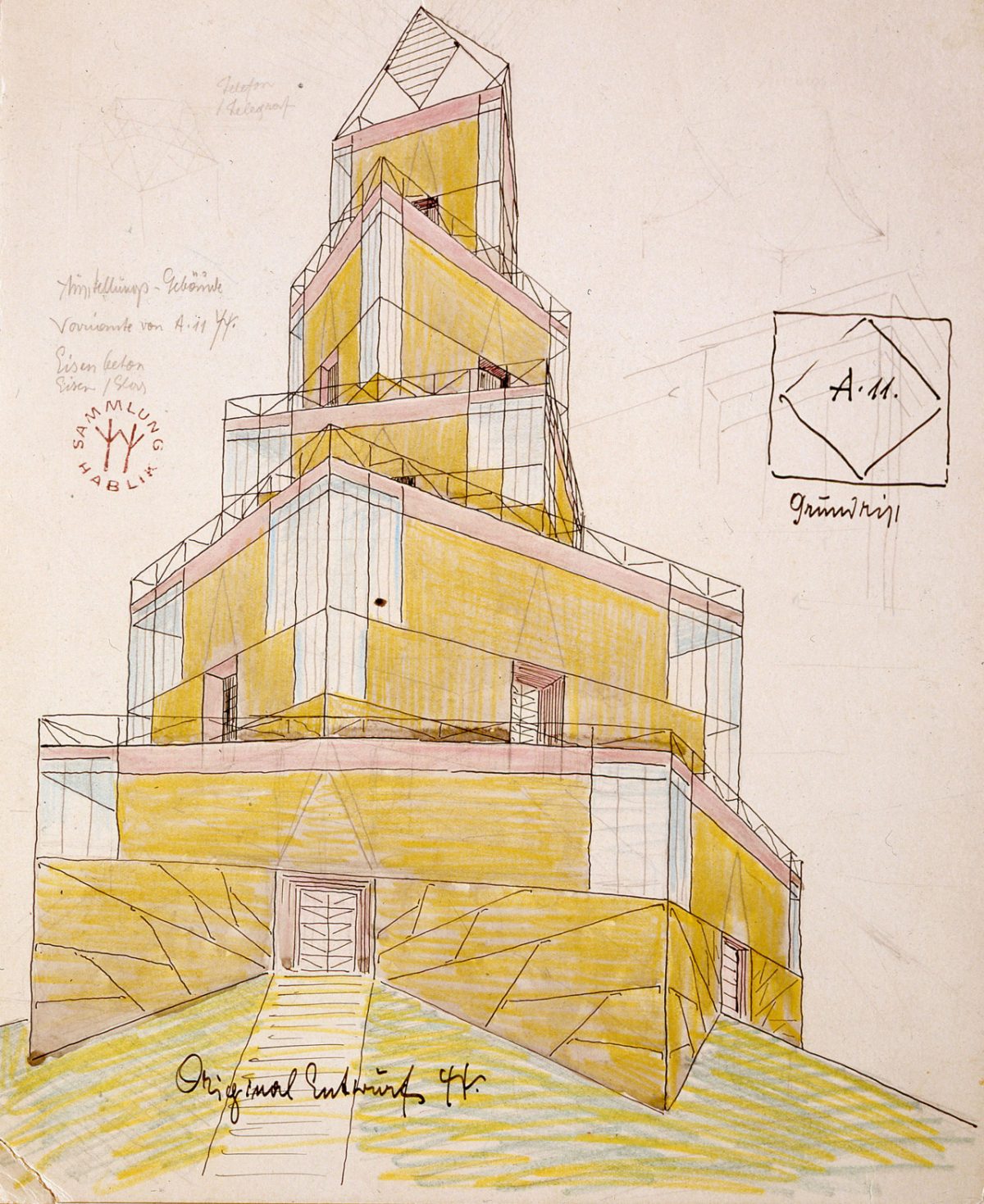

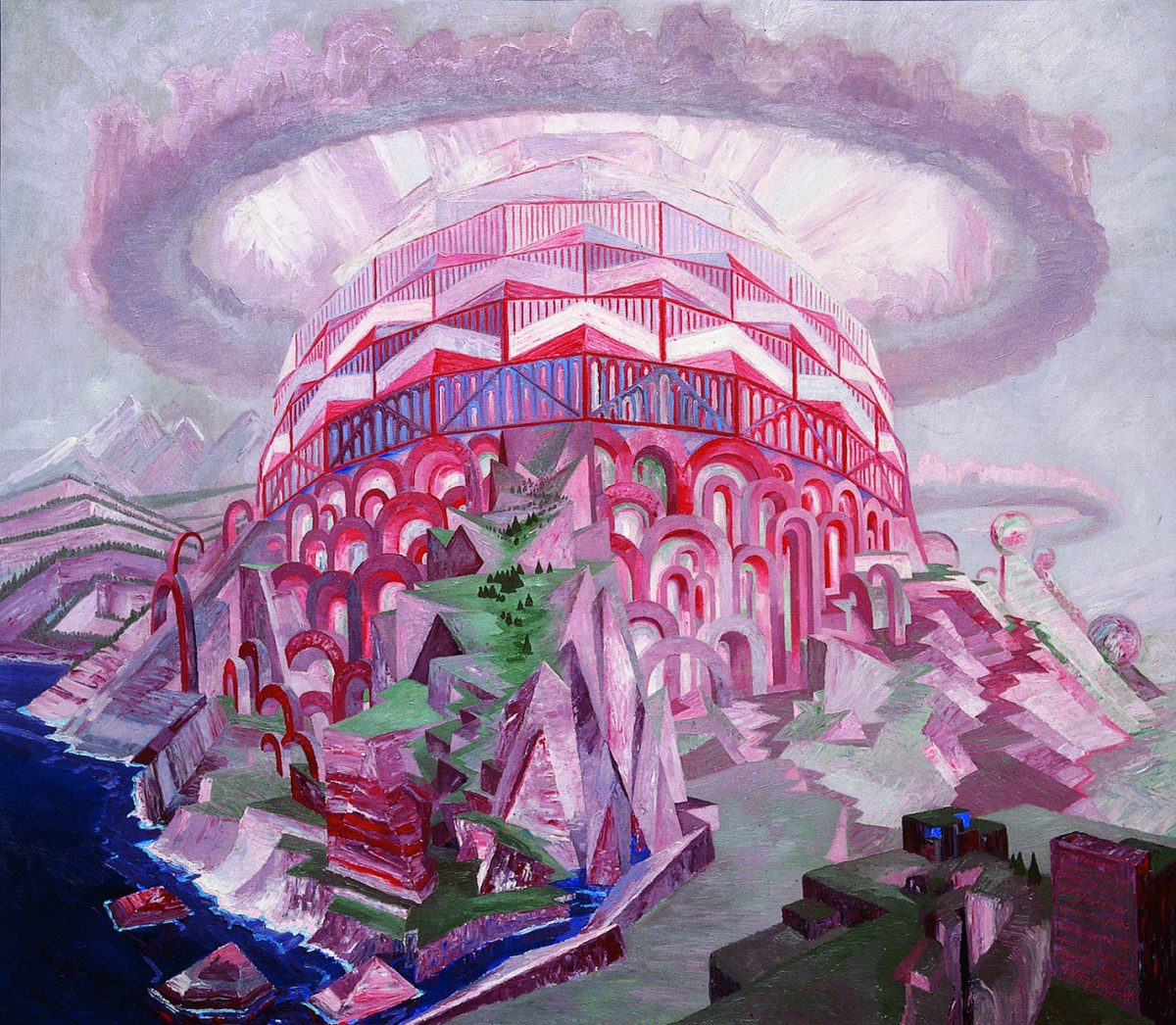

Design for an Exhibition Building is a Futurist and Art Nouveau watercolor and pen painting created by Wenzel Hablik in 1919

His career got boost when during a trip to the German island of Helgoland, Hablik met the wealthy timber merchant Richard Biel who became his friend and patron. In 1907, Hablik permanently settled in Itzehoe, Biel’s hometown near Hamburg, working on architectural and interior design projects, designing furniture, textiles, tapestries, jewellery, cutlery and wallpaper.

From 1908, he designed interior decorations for Biel and other wealthy families in northern Germany. Shortly after his arrival in Itzehoe, Hablik met the weaver and fabric designer Lisbeth Lindemann (1879–1960). They shared a workshop and studio in Itezhoe, and married in 1917.

Crystal Castle in the Sea, 1914. You can buy prints of his work in the shop.

Exhibition Space Wallpapers is a Futurist and Art Nouveau artwork created by Wenzel Hablik in 1921. Prints.

After the war, the couple moved into a villa in Itzehoe which became an artwork in itself (Gesamtkunstwerk). The place was home to studios specialising in metal work and gemstone cutting, and collections of minerals, small creatures and plants.

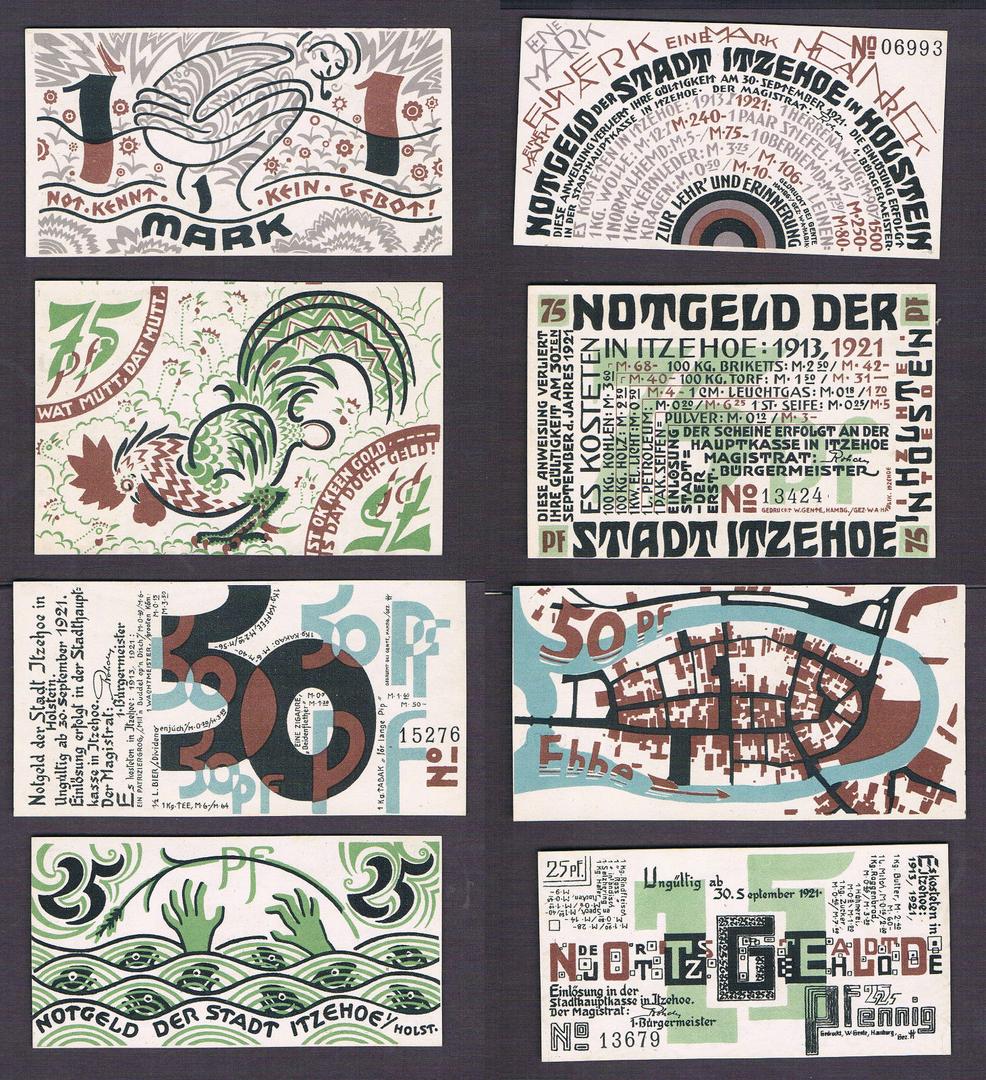

He also designed Notgeld (emergency money), which was issued by cities, boroughs, and private companies when hyperinflation gripped Germany in the 1920s. Notgeld replaced the official currency as the German Mark’s value plummeted. After the economic necessity for it had passed at the end of WW1, Notgeld was printed as collectors’ items. Hablik had some fun with the money. For example, the 1 mark (below) shows a figure defecating in the countryside and declares “NOT KENNT KEIN GEBOT” (NECESSITY HAS NO LAW ALL MY ITEMS ARE GENUINE 100% ORIGINAL).

Wenzel Hablik’s norgeld

In 1919, Hablik accepted an invited by Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius to participate in the Exhibition of Unknown Architects organised by the Berlin-based union of artists and artisans Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Art Soviet), whose stated aim echoed that of other art groups of the period, including theeWiener Werkstätte: “Art and the people must form an entity. Art shall no longer be a luxury of the few but should be enjoyed and experienced by the broad masses. The aim is an alliance of the arts under the wing of great architecture.”

Hablik, Gropius and many of other artists in the group formed Die Gläserne Kette (The Crystal Chain), a community of artists that included Paul Goesch, Hans Hansen, Carl Krayl, Hans and Wassili Luckhardt, Hans Scharoun, Bruno and Max Taut, and Hermann Finsterlin. They debated the future and their visions of an ideal society. The Glass Chain collection is housed in the Hans Scharoun Archive in the Archives of the Academy of Arts, Berlin.

Design for a Great Hall is an Art Nouveau oil on canvas painting created by Wenzel Hablik in 1924.

Cantilever Cupola with Five Hilltops is a Symbolist oil on canvas painting created by Wenzel Hablik in 1924.

Utopian Buildings is a Futurist oil on canvas painting created by Wenzel Hablik in 1922.

The Wenzel Hablik Museum was established in Itzehoe in 1995. The museum contains much of his art, as well as his collections of crystals and minerals, seashells and snails.

Cathedral Interior is a Futurist oil on canvas painting created by Wenzel Hablik in 1921

You can buy prints of his work in the shop.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.