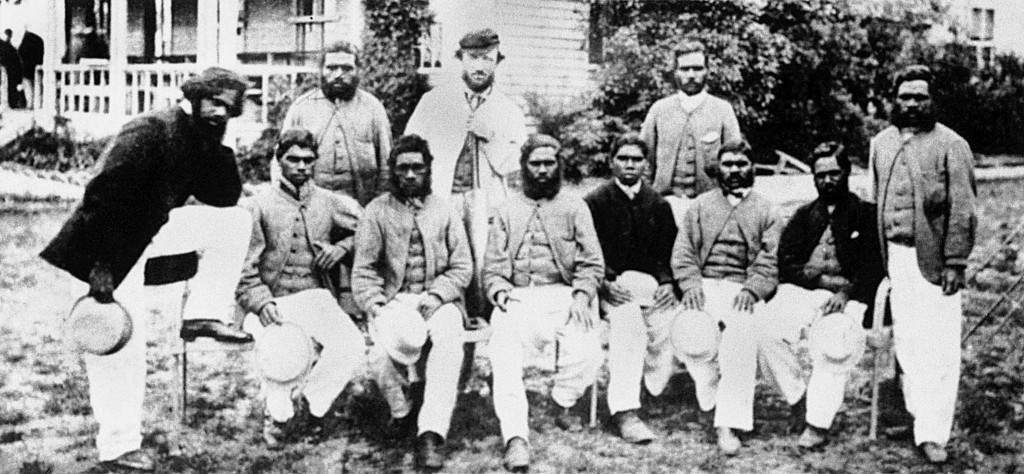

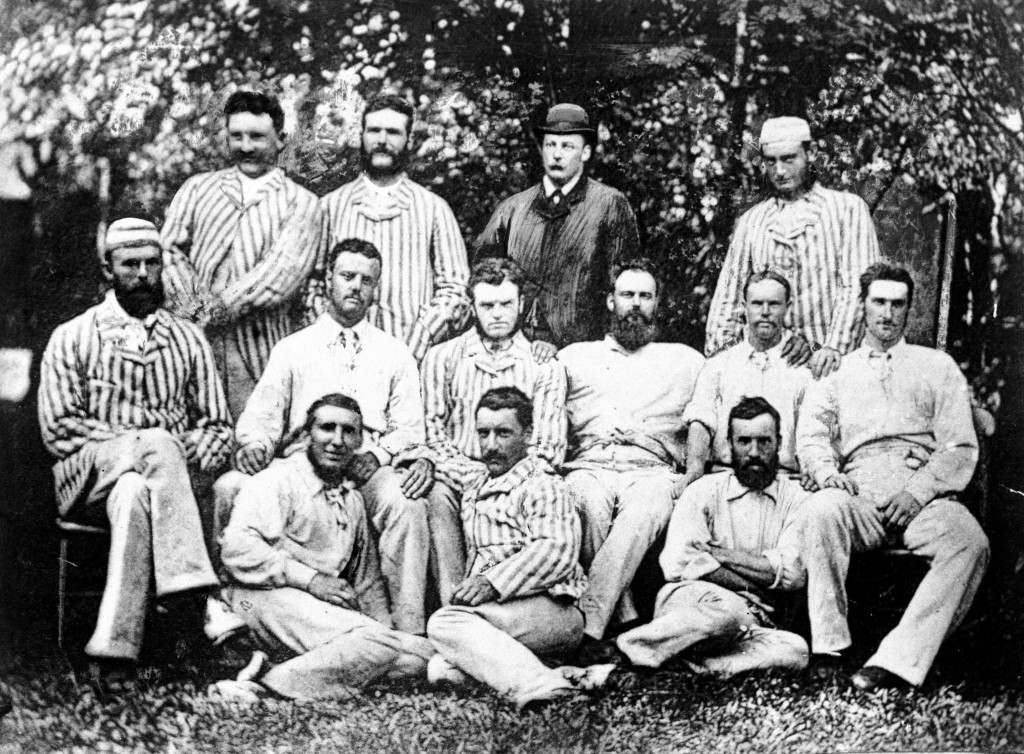

On February 2 1867, the first Australian cricket team to tour England posed for a photo at the Albert Ground, Sydney:

The team were:

(back row, l-r) Tarpot, TW Wills, Johnny Mullagh (front row, l-r) King Cole, Jellico, Peter, Red Cap, Harry Rose, Bullocky, Cuzens, Dick-a-Dick

This was less a sporting contest of equals than a circus show.

The highbrow London Times said it was a travesty the conquered natives of a convict colony were allowed to appear at Lord’s…

The team was created by a British-born Aussie:

Charles Lawrence captained the first Australian team to tour England. He was born in London in 1828 and became a professional cricketer at the age of 17. He played in Ireland during the 1850s and formed the United All-Ireland XI. In 1861-62 he toured Australia with the first England Team under H.H. Stephenson. At the end of the tour he remained behind to coach the Albert Club in Sydney. In 1868 he captained a team of 13 Aboriginal cricketers to England. After returning to Australia Lawrence continued playing and coaching. He played his last game at the age of 70 and died in 1916.

The BBC gives us some background to the tour:

In 1868, English ex-pat and former first class cricketer Charles Lawrence brought a team of 13 Victoria-based Aboriginal players to the UK, intent on capitalising on public curiosity regarding “exotic races” following the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859.

But if the players were from Victoria why were they pictured at the Sydney, New South Wales, ground?

The tour faced strong opposition from the Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines (CBPA) in Victoria, which feared that the Aboriginal players would struggle to survive the dismal English weather – it turned out to be a good summer, though the tour continued until October.

Concern had been heightened by the deaths of four players during and immediately after an abortive Sydney tour the previous year, at least two of them from pneumonia. Lawrence was therefore forced to smuggle the players from Victoria into Sydney, where they boarded a wool-carrying clipper bound for the UK on 8 February 1868.

The CBPA were not all that caring about the natives. They were bigots detailed to keep them apart from decent society. In 1869, the state of Victoria brandished the Aboriginal Protection Act:

Victoria enacted this law to regulate the lives of Aboriginal people at the same time as democratic reforms were being achieved in Britain and the Australian colonies. These reforms included extending the right to vote to all men, not just the wealthy, and measures such as free public education. For Aboriginal people, however, there was no such progress. The powers this Act gave to the Board for the Protection of Aborigines developed into controls over where people could live, where they could work, what kinds of jobs they could do, who they could associate with and who they could marry.

In 1886 in a further Act, Victoria also initiated a policy of removing Aboriginal people of mixed descent from the Aboriginal stations or reserves to merge into white society. The Board refused assistance to those it expelled from the reserves. This effective separation of communities and family members caused distress and protest. People like Bessy and Donald Cameron, who lived on the reserve at Ramahyuck (Lake Tyers), fought to stay together after Victoria’s ‘half-caste’ Act made this unlawful in 1886.

The policy of excluding so-called ‘half-castes’ assumed that numbers of Aboriginal people on the reserves would decline, so that reserves could be reduced and eventually closed down. The inadequacy and inhumanity of the policy and legislation led to the Aborigines Act 1910 (Vic) and the Aboriginal Lands Act 1970 (Vic).

One extract:

All bedding clothing and other articles issued or distributed to the aboriginals by or by the direction of the said Board shall be considered on loan only and shall remain the property of Her Majesty, and it shall not be lawful for the aboriginals receiving such bedding clothing and other articles to sell or otherwise dispose of the same without the sanction of the Minister or such other person as the said regulations may direct.

The Queen covers you in her love even in your sleep. And she wraps you in her hard embrace in your waking hours. There is no escape:

If any person shall without the authority of a local guardian take whether by purchase or otherwise any goods or chattels issued or distributed to any aboriginal by or by the direction of the said Board (except such goods as such aboriginal may be licensed to sell) ; or shall sell or give to any aboriginal any intoxicating liquor except such as shall be bonâ fide administered as a medicine, or shall harbor any aboriginal unless such aboriginal shall have a certificate or unless a contract of service as aforesaid shall have been made on his behalf and be then in force, or unless such aboriginal shall from illness or from the result of any accident or other cause be in urgent need of succour and such cause be reported in writing to the Board or a local committee or local guardian or to a magistrate within one week after the need shall have arisen or shall remove or attempt to remove or instigate any other person to remove any aboriginal from Victoria without the written consent in that behalf of the Minister every such person shall on conviction be liable to a penalty not exceeding Twenty pounds or in default to be imprisoned for any term not less than one month nor more than three months.

So much for the backstory.

The tour lasted “six gruelling months… they played 47 two-day games. At the completion of each game the team was required to give an exhibition of ‘native sports’, including boomerang and spear throwing.”

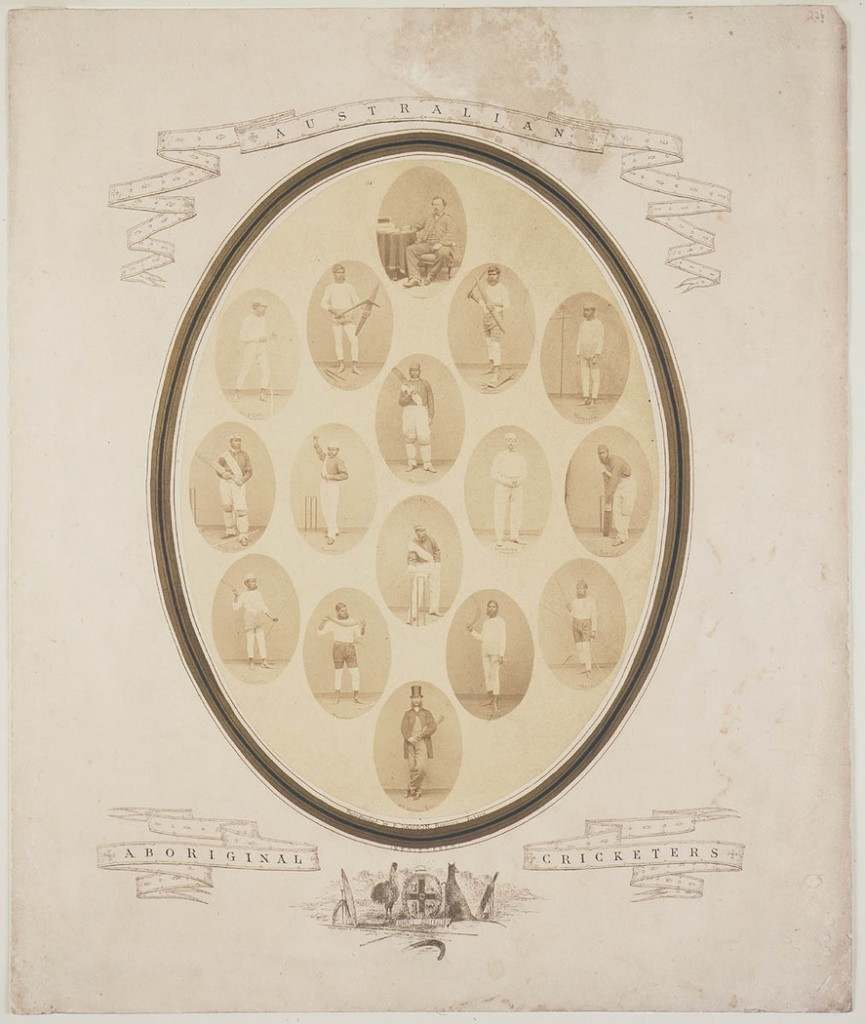

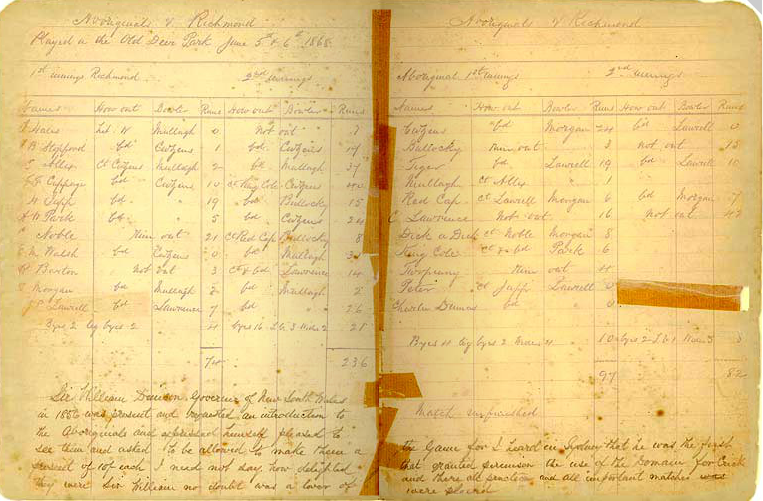

The Scorebook of the Aboriginal Cricket Tour of England is a copy, in Charles Lawrence’s hand, of the original scorebook. It records names of both teams for all innings, scores, results, umpires’ names and other details for every match. The scorebook also includes scores for 22 of Dublin v United Ireland Xl, 1856 and United Ireland XI v 22 of the North of Ireland, 1860. (via)

John Mulvaney and Rex Harcourt’s Cricket Walkabout: The Australian Aborigines in England has more. Ric Sissons notes:

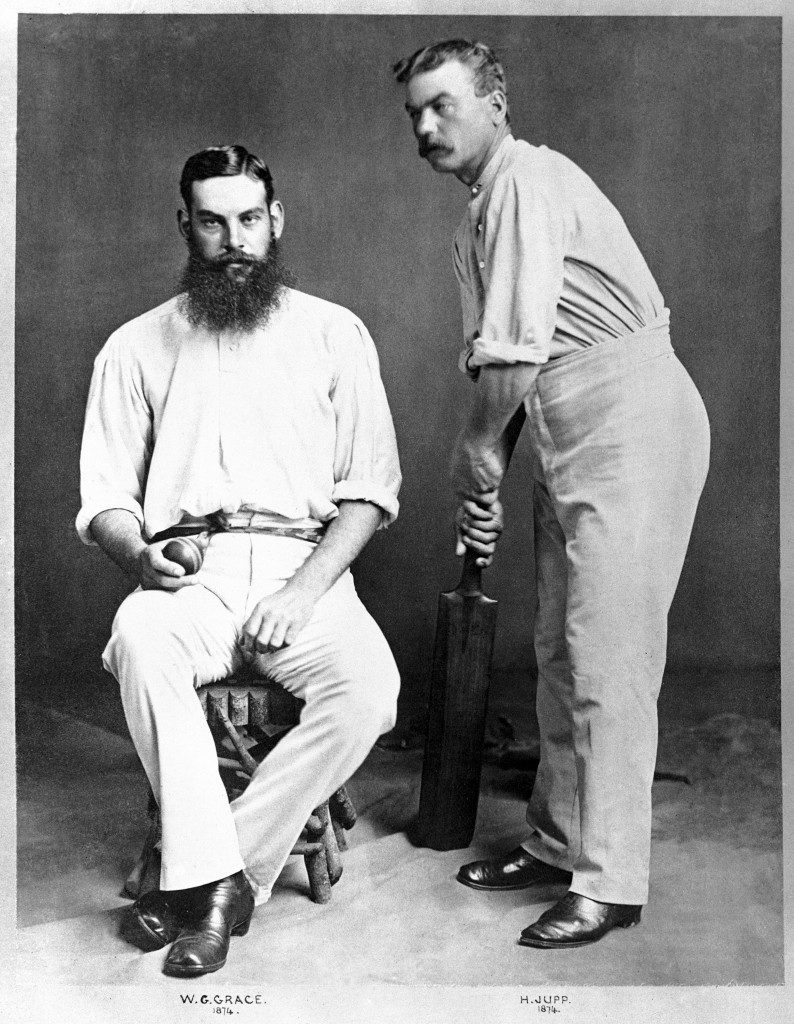

Mulvaney and Harcourt divide the opposition the tourists faced into three categories. The first and most important includes seven teams against whom the Aborigines played ten matches. These 7 side correspond with familiar county teams today, although not in standard’. The crucial point that Mulvaney and Harcourt omit to mention is that these elevens were in every case ‘The Gentlemen of’ the county and not the representative county side. In other words the county’s professionals were excluded. For examples the Aborigines met the ‘Gentlemen of Surrey’ on three occasions but absent from the local side were notable players such as Thomas Humphrey, Henry Jupp (Mulvaney and Harcourt wrongly attribute his career record to the amateur G.H. Jupp who did play against the Aborigines), George Griffith, Edward Pooley and H.H. Stephenson. Similarly when the tourists travelled to Yorkshire the ‘county’ side did not include professionals; among the absentees were Ned Stephenson, George Freeman, Roger Iddison and Tom Emmett. The description of the best opposition the Aboriginal tourists faced as ‘county’ is misleading and overstates the case. Further in the ten matches against these gentlemen-county combinations the Aborigines managed only four draws and suffered six defeats by wide margins. It is no disgrace to accept the assessment made by W.G. Grace that the Aboriginal tourists were ‘equal to third-class English teams’. After all, the team was drawn from one region in western Victoria.

Other matches included: Aboriginals v Gentlemen of Lewisham and Aboriginals v Gentlemen of Sussex.

(L-R) WG Grace, Gloucestershire and England, and Henry Jupp, Surrey and England

Ref #: PA.479205. Date: 01/04/1874

Afterwards:

Under the captaincy of Charles Lawrence, the team produced one legendary player, a young man called Muarrinim. Known on tour as Johnny Mullagh, he scored 1698 runs and claimed 245 English wickets over 45 games. He went on to play for the Melbourne Cricket Club.

After the tour most of the players died in obscurity with only a few playing top class cricket again. Johnny Mullagh played for Victoria against Lord Harris’ English team in 1879 top scoring in the second innings. He became a professional at the Melbourne Cricket Club and died in 1891. Johnny Cuzens also played for Melbourne as a professional before going bush in 1870. He is believed to have died the following year. The only other player to appear again in big cricket was Twopenny who played for NSW against Victoria in 1870.

From this first tour, a tradition was established which continues to this day. In 2001 the most recent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island squad, the ‘Downunders’, played nine one-day games, including four ‘re-enactment’ games to commemorate the original 1868 tour.

The Aborignis were not classifed as Australians. Records say that the first Australia team to your Englnd arrived in 1878. And, no, not a single Aborigini was in its ranks:

The first official Australian side to visit England: (back row, l-r) Billy Midwinter, George Bailey, ?, Frank Allan; (middle row, l-r) Harry Boyle, Billy Murdoch, Tom Horan, Dave Gregory, Alec Bannerman, Frederick Spofforth; (front row, l-r) Tom Garrett, Charles Bannerman, Jack Blackham

Ref #: PA.625125. Date: 25/05/1878

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.