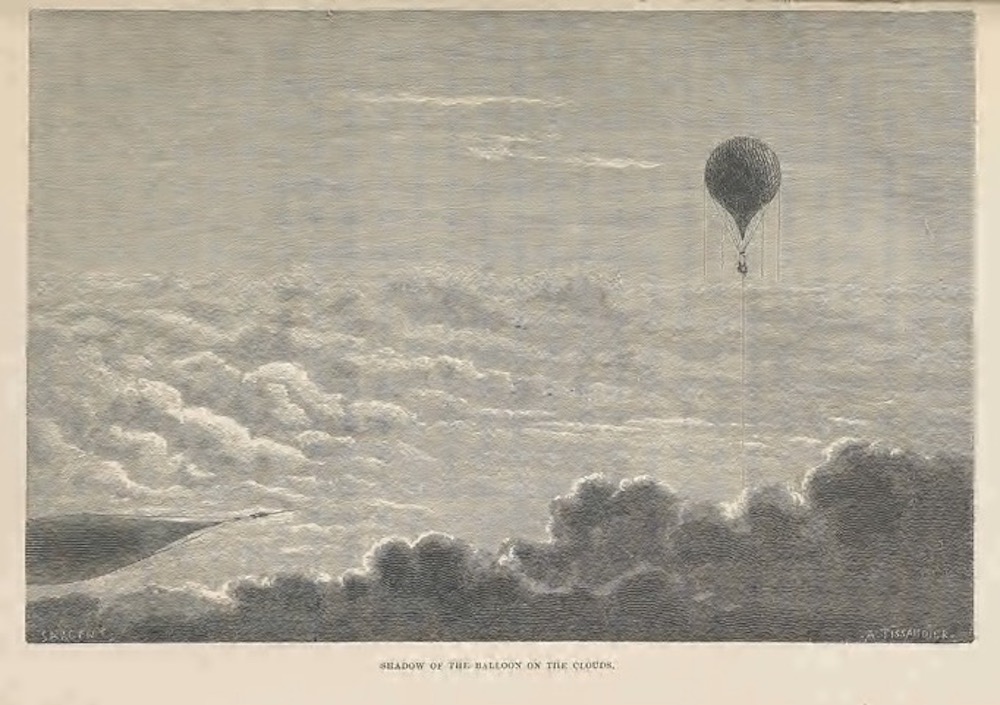

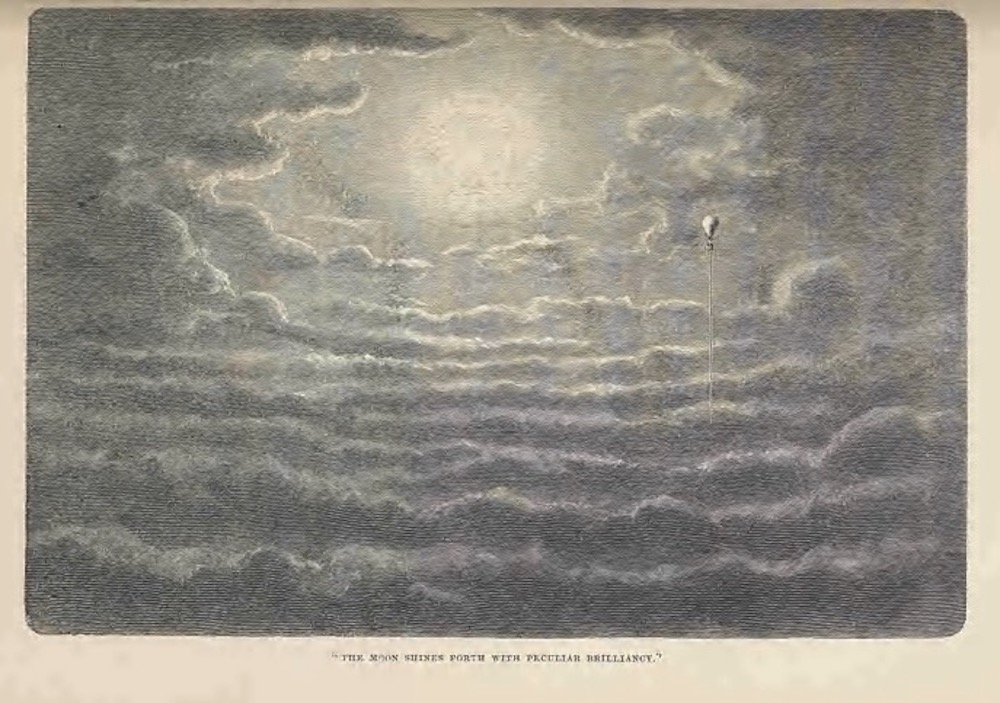

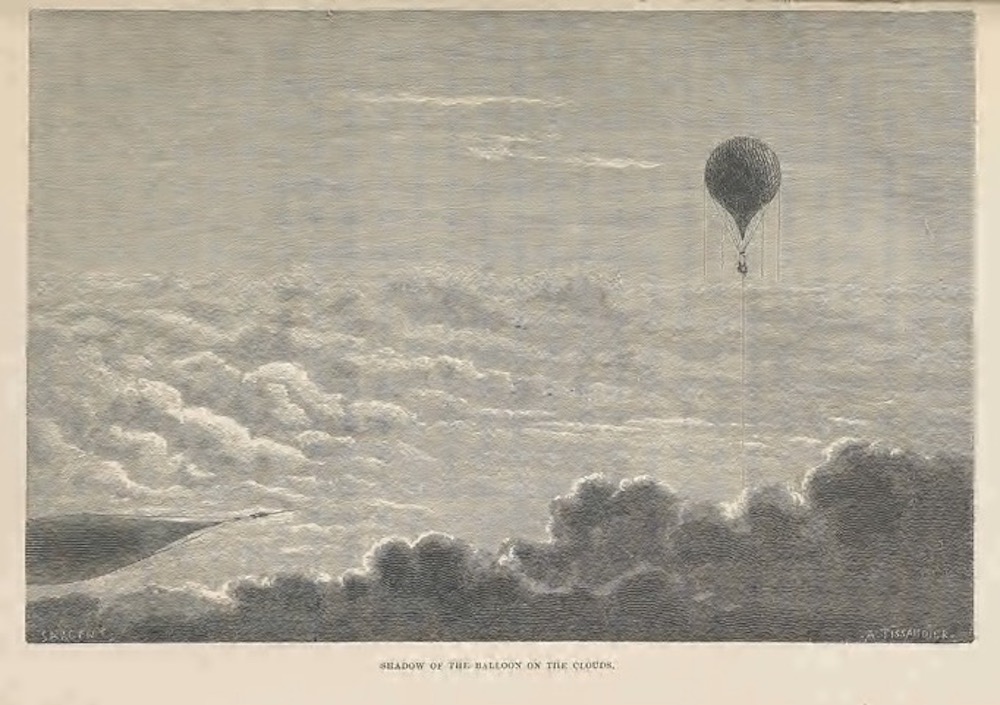

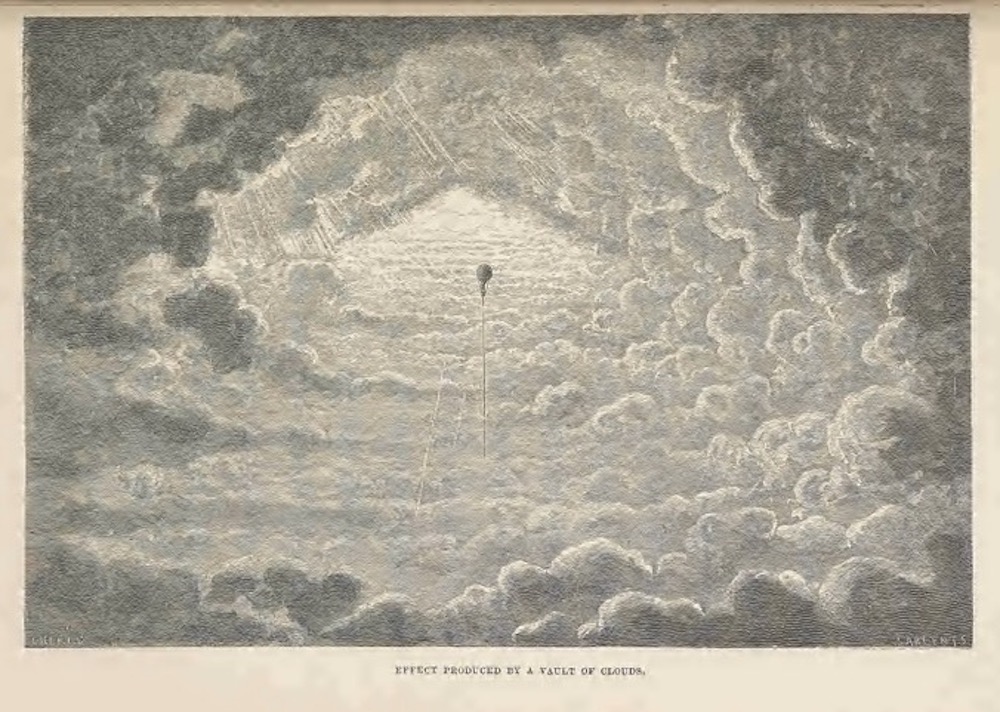

“The balloon was isolated, as if it were in a vacuum; beneath us stretches an immense abyss, above the infinite expanse of sky”

– James Glaisher, Travels In The Air, 1871

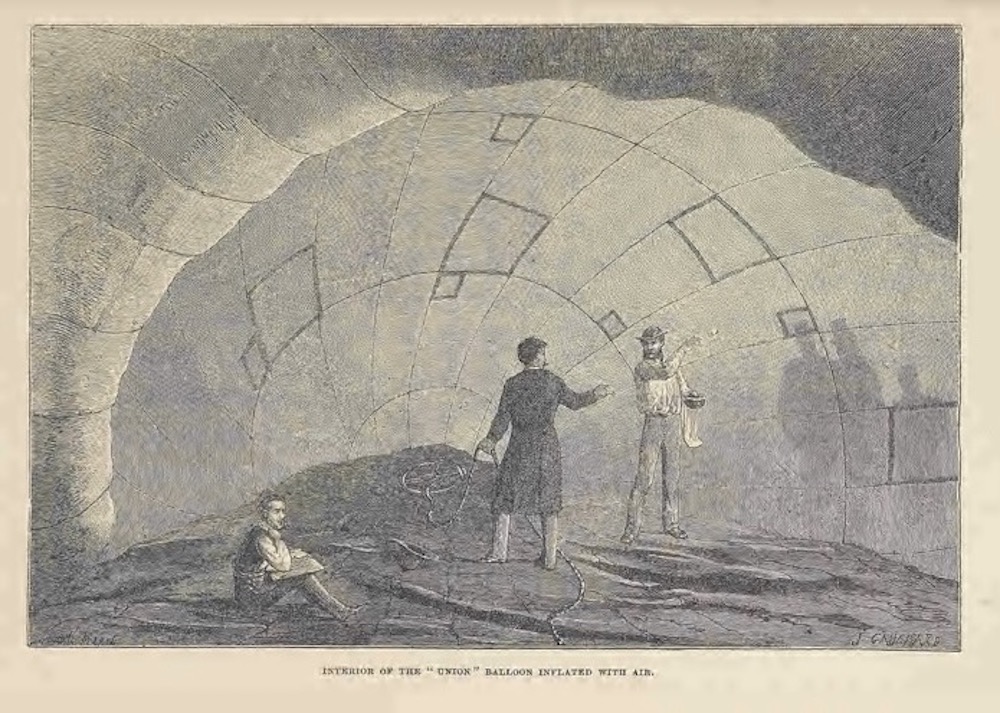

Travels in the Air tells the story of balloon travel since the first ‘aerostatic’ flight by the Montgolfier brothers at Versailles in 1783 and their fellow French brothers Anne-Jean Robert (1758–1820) and Nicolas-Louis Robert (1760–1828), who built the world’s first hydrogen balloon for professor Jacques Charles, which flew from central Paris on 27 August 1783.

Les Frères Robert went on to build the world’s first manned hydrogen balloon, and on 1 December 1783 Nicolas-Louis accompanied Jacques Charles on a 2-hour, 5-minute flight. Their barometer and thermometer made it the first balloon flight to provide meteorological measurements of the atmosphere above the Earth’s surface.

As James Glaisher FRS (7 April 1809 – 7 February 1903), an English meteorologist, aeronaut and astronomer, writes in the introduction to Travels in the Air, balloon flight “has gratified the desire natural to us all to view the earth in a new aspect, and to sustain ourselves in an element hitherto the exclusive domain of birds and insects. We have been enabled to ascend among the phenomena of the heavens, and to exchange conjecture for instrumental facts, recorded at elevations exceeding the highest mountains of the earth.”

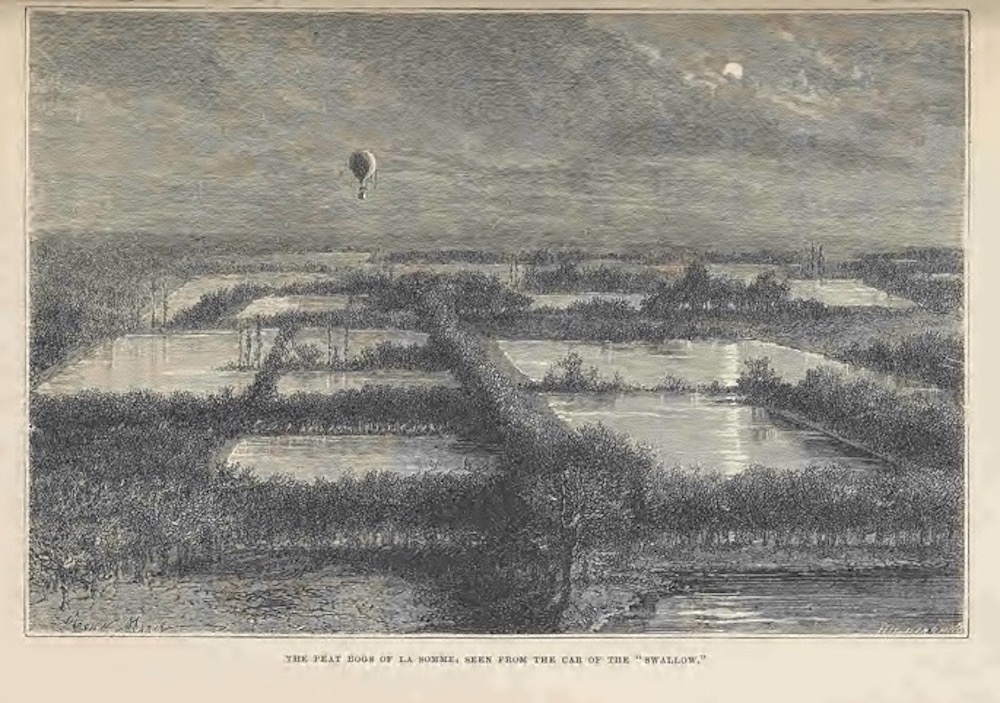

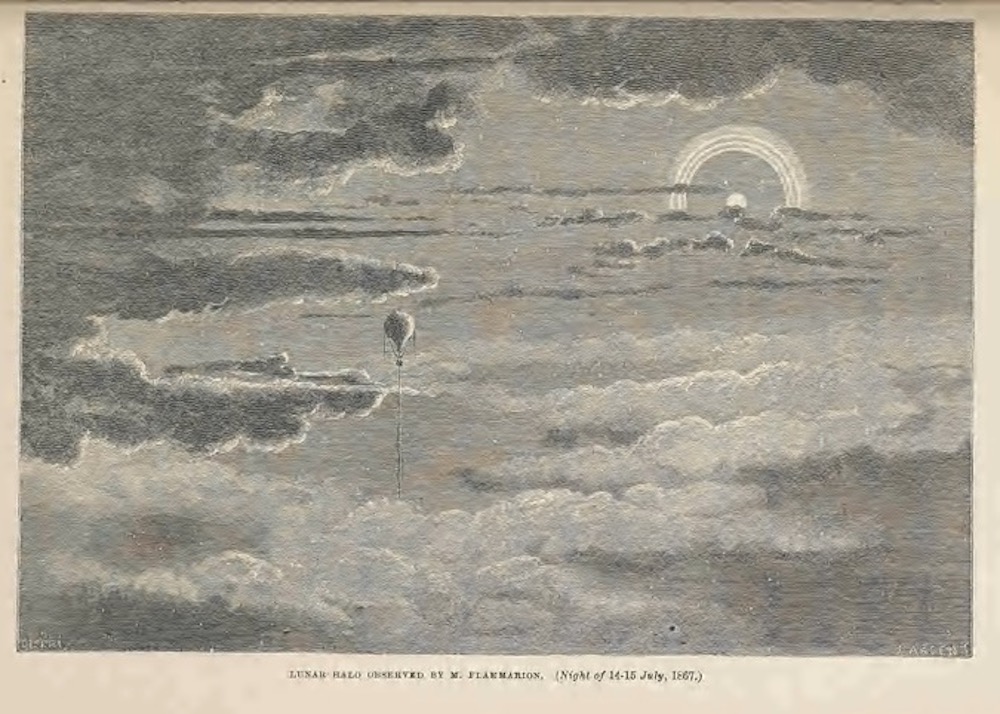

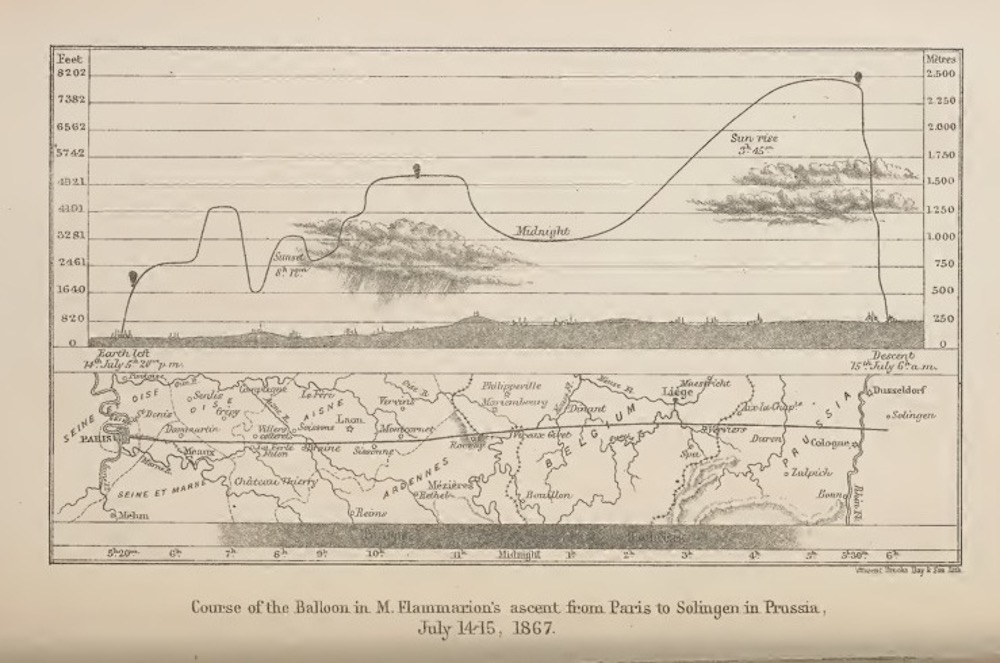

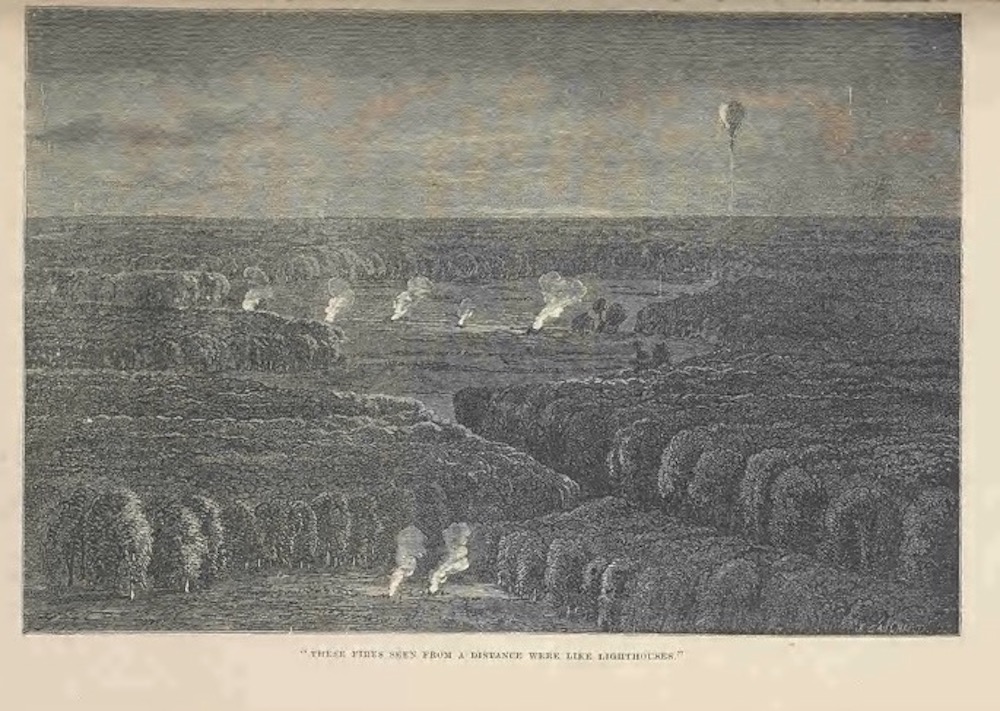

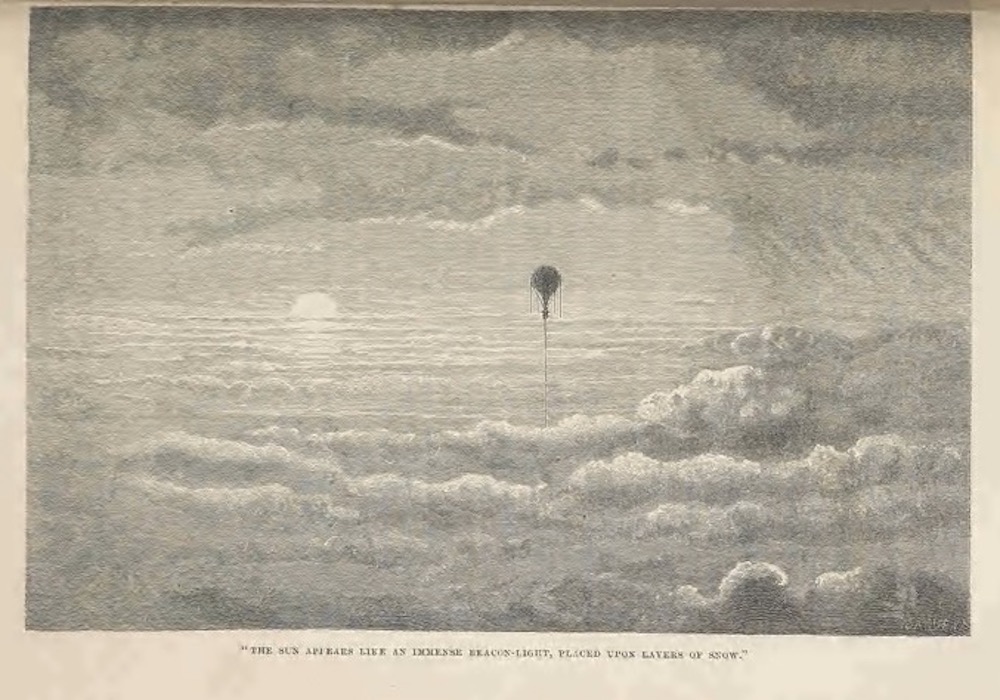

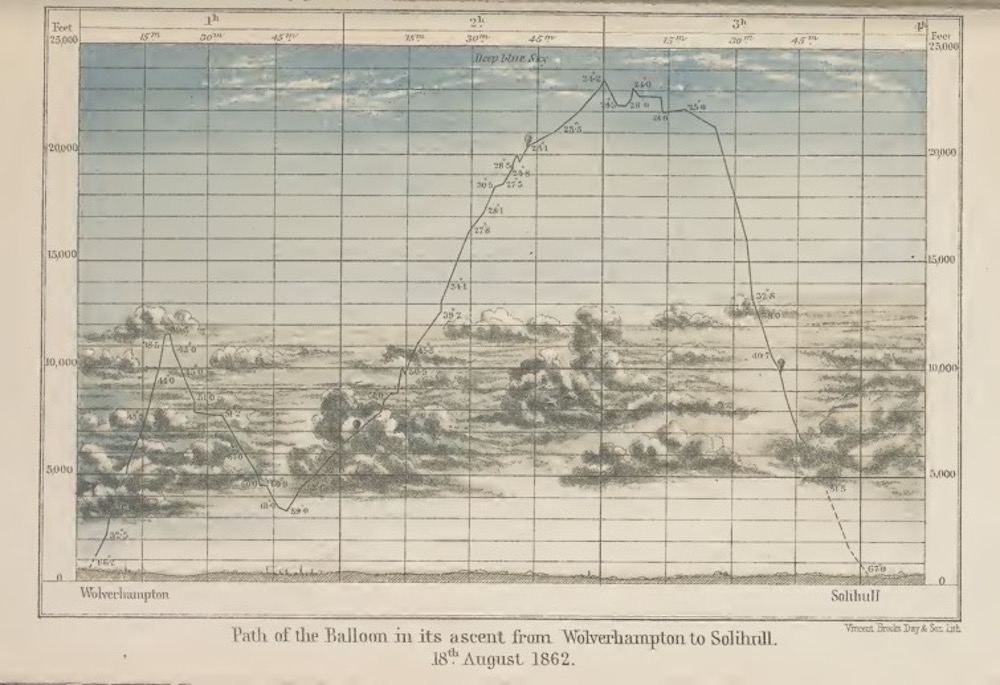

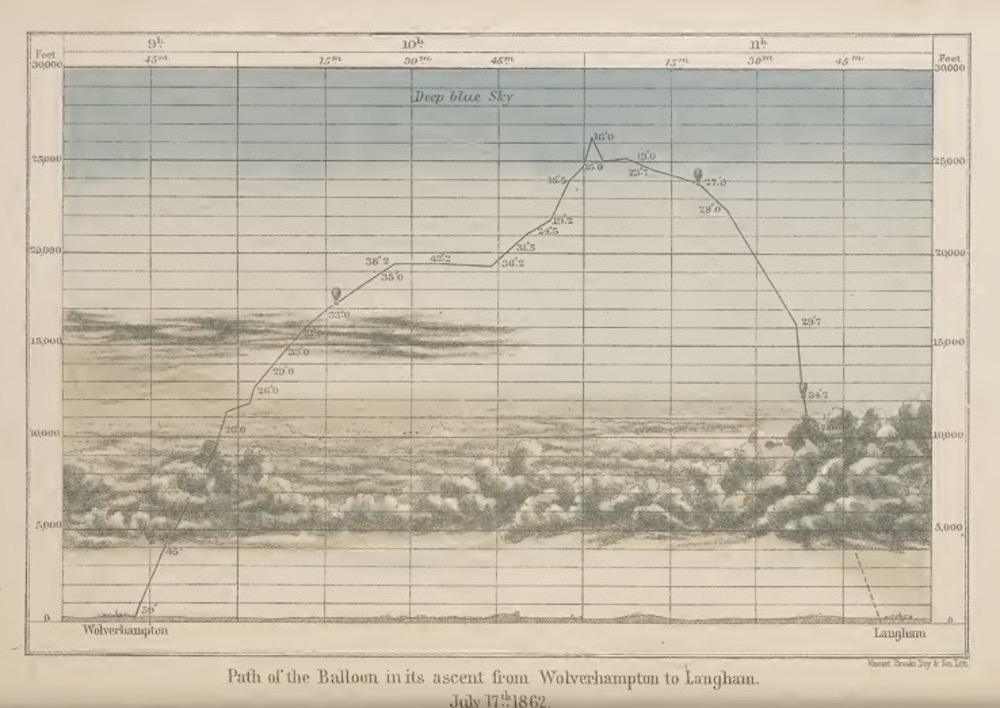

Told with illustrations of adventures in the air and his own flights over England and Europe among the birds and bugs (on one flight butterflies flock around his balloon), there are charts of the data Glaisher recored on instruments to measure the temperature, barometric pressure and chemical composition of the air. He even recorded his own pulse at various altitudes.

The book was authored by Glaisher, with illustrations and data attributed to prolific French astronomer and author Camille Flammarion (1842-1925), French science writer and balloonist Wilfred de Fonvielle (1824-1914) and French chemist, meteorologist and aviator Gaston Tissandier (1843-1899).

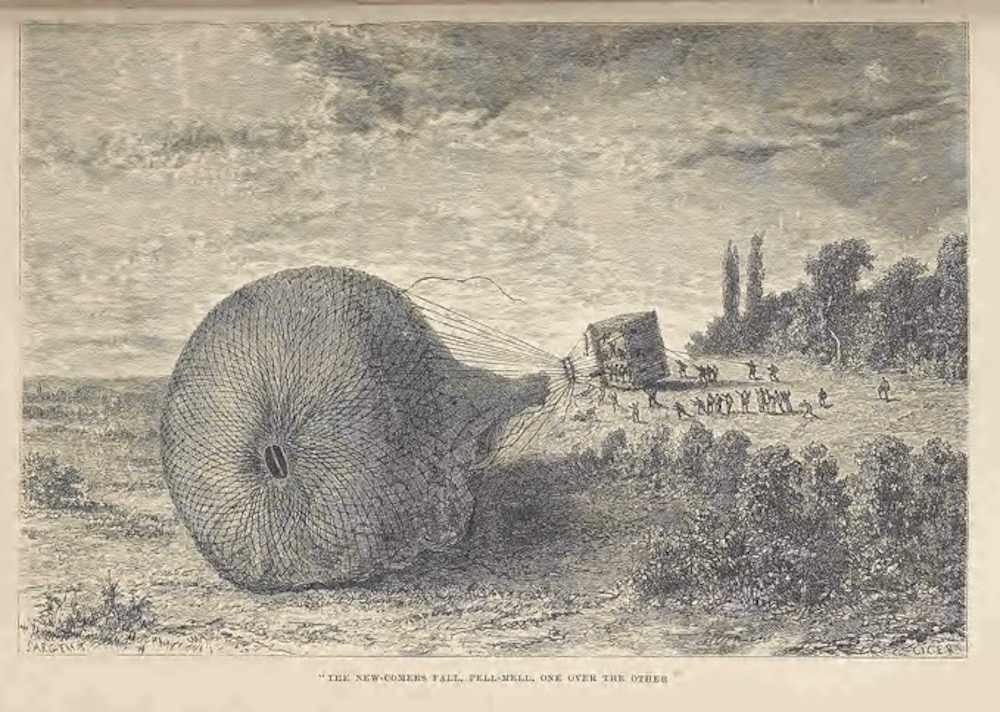

Please note: The illustrations are small in size and the smaller captions beneath them unclear in the original book.

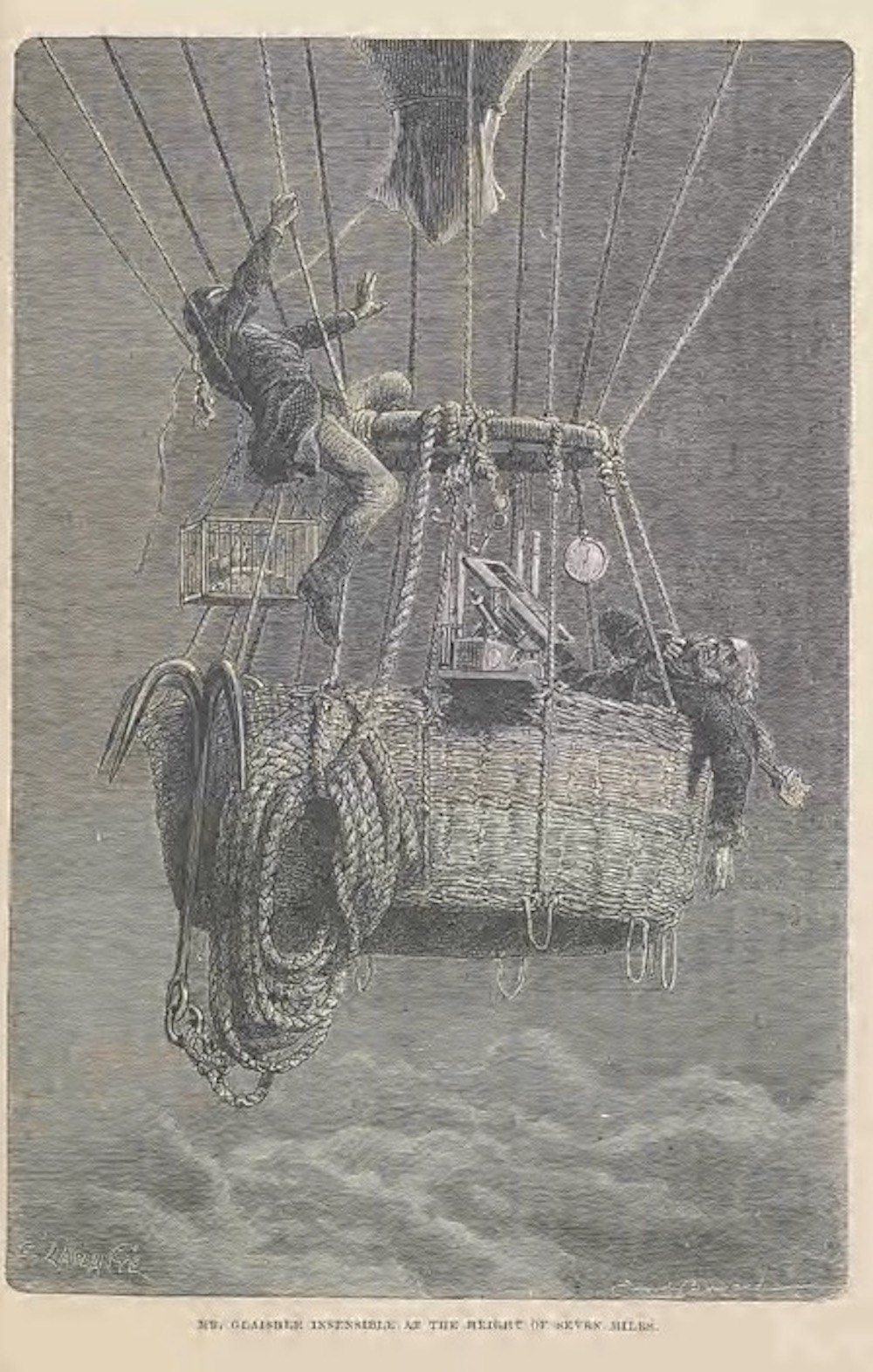

At six and seven miles high, I experienced the limit of our power of breathing in the attenuated atmosphere. More frequent experiments would increase this height, I have little doubt, and artificial appliances might be contrived to continue it higher still.

The rarity of the atmosphere now began to affect us, and, as the disorder arising from this cause was more impartial than the distribution of muscular activity, our condition was for a time almost equalized. Violent nausea and headache were experienced by one of our party, while I only felt, in addition to the distress of increasing weakness, the taste or scent of blood in the mouth, as if it were about to burst from the nostrils.

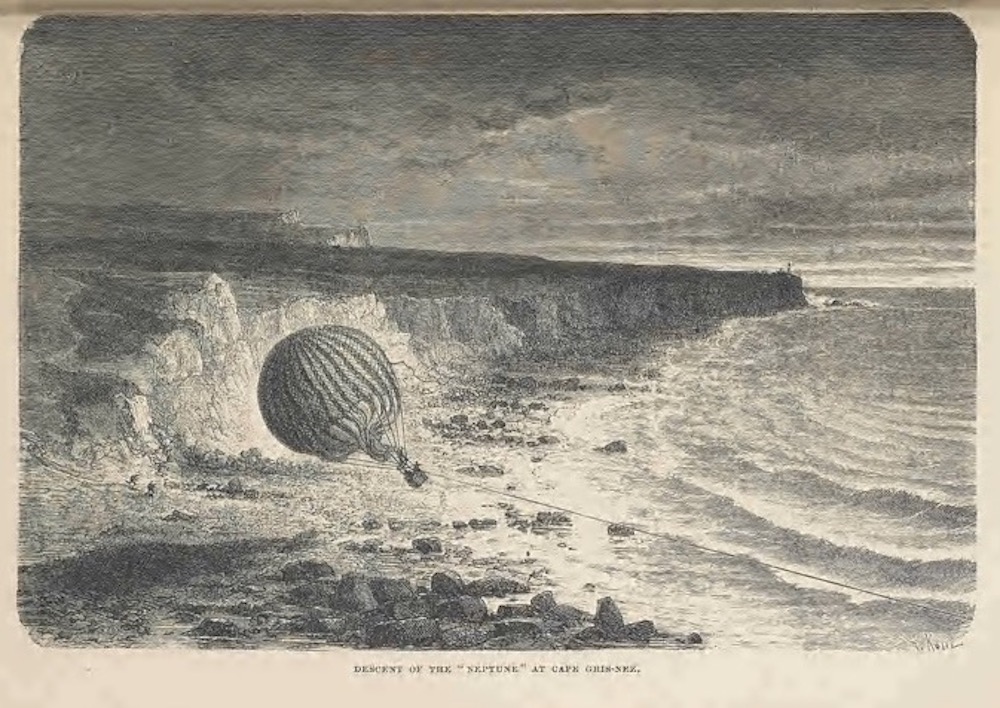

In January 1785, M. Blanchard and Dr. Jeffries crossed the Channel in a hydrogen balloon from Dover to Calais. Irom some defect in the gas, or deficiency in its amount, far from being affected by the rarity of the air, they could with difficulty keep themselves at a level above the sea, and to do so were obliged to part with everytliing in the car, and even take off their clothes and throw them overboard. As they neared the land, however, the balloon rose, and, describing a magnificent arch, carried them over the high ground surrounding Calais, and finally landed them in the Forest of Guiennes.

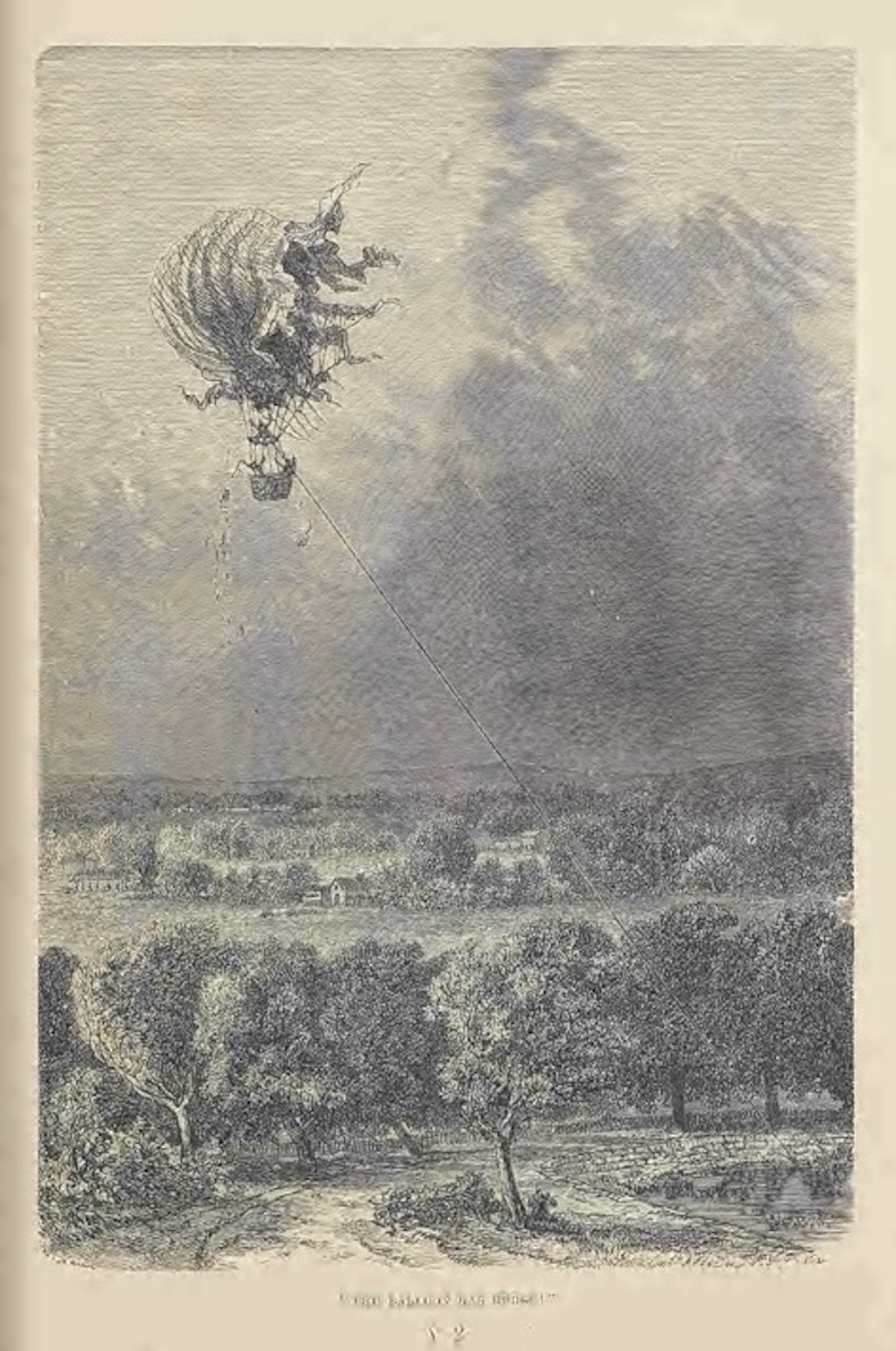

On July 22, Signor Lunardi ascended from Liverpool. The process of filing the balloon was tedious, and the impatience of the populace made it necessary to ascend before the process of inflation could be properly formed. He therefore found himself with barely enough rising powder to carry him, and without ballast of any kind; so that when after being becalmed he was gently wafted towards the sea, he had not balast to throw out to enable him to rise and meet some other current. When suspended over the sea, to lighten his w^eight he threw down his hat, upon which the balloon rose, and the thermometer fell 3°. The

balloon entered a cloud, and, with the thermometer at 50°,Lunardi was surprised at finding himself surrounded with a shower of snow. Being desirous to ascend higher, he threw down his banner, and shortly after took off his coat (the uniform of the Honourable Artillery Company) and threw it away. He then rose majestically, and bore towards the land. Ten mimites later he perceived a thunder-cloud, and signs’ of a gathering storm. To pass from its vicinity he threw down his waistcoat. The temperature had fallen to 32°, and five minutes later fell to 27° ; the snow had melted on the top of his balloon, and had trickled down in the form of water. It was now congealed in the colder temperature, and hung in icicles round the neck of the balloon; he shook off about a pound’s weight, and it fell upon the floor of the gallery, Lunardi looking upon it as the ballast of Providence. The temperature descended to 26″. He now began to descend. It was three minutes to seven, and six minutes after he was safely landed in a cornfield about twelve miles from Liverpool.

M. Pilatre de Eozier and M. Eomain had made their last and fatal voyage from Boulogne. The balloon employed was compound, a small fire balloon being appended to a hydrogen balloon above. The one set fire to the other, and the aeronauts were precipitated to the earth and killed.

On October 7, 1803, Count Zambeccari, Dr. Grassati, of Eome, and M. Pascal Andreoli, of Ancona, made a night ascent in a fire-balloon from Bologna. They took with them instruments, and a lantern, by which to see to make observations. The balloon rose with great velocity, and soon attained a height at which Count Zambeccari and Dr. Grassati became insensible. M. Andreoli retained the use of his faculties. About two in the morning they found themselves descend.ing over the waves of the Adriatic ; the lantern had gone out, and to light it was a work of no little difficulty. The balloon continued to descend rapidly, and fell, as they anticipated, into the sea. Thoroughly drenched, they succeeded in throwing out ballast until they rose again…

[They] passed through three successive regions of cloud, which covered their clothes with rime, and in this situation they became deaf, and could not hear each other speak. About three o’clock the balloon again descended, and was driven by a gust of wind to the coast of Istria, bounding in and out of the sea till eight o’clock in the morning, when one Antonio Bazon picked them up in his ship, and carried them to shore. The balloon, left to itself, went over to the Turks, having first mounted to an amazing height. The most intense interest was excited for the fate of the aeronauts, and bulletins of health were sent from Venice to Bologna. Count Zambeccari suffered most, and was forced to have his fingers incised. The whole of the party, however, ultimately recovered, and Count Zambeccari, in no way intimidated, continued to persevere in making ascents to a consider- able height.

It is not to be supposed that additional frequency of respiration in an attenuated air makes amends for the want of oxygen. Those who have felt the continued dryness of the throat, which is parched so that to swallow is painful, are sensible to the contrary but the death it produces is painless, and asphyxia steals away the life of the human being as he moves above, suspended in mid-air, as stealthily as cold does that of the mountain traveller, who, benumbed and insensible to suffering, yields to the lethargy of approaching sleep, and reposes to wake no more.

By the reading of the barometer in the balloon, the distance from the earth is known; and if the balloon be situated above clouds, or in a fog, the reading of the barometer indicates the near approach of the earth, and acts as a warning to the occupants of the car to prepare accordingly. In addition to this temporary use, the readings combined with those of temperature enable us to calculate the height of the balloon at every instant at which such readings have been taken.

To those who look upon aeronautic expeditions as frivolous, and not worth the attention of scientific men, I cannot do better than quote the following words pronounced by Arago on the ‘occasion of Gay-Lussac’s ascents.

“Beautiful discoveries,” he said, “will reward those who make scientific excursions in balloons. It is much to be deplored that those ascents which are made almost every week in more and more dangerous circumstances, and which must accidentally terminate in some fearful catastrophe, should have the effect of causing scientific men to give up their proposed ascents. I understand their scruples, but do not share them. The spots on the sun, the mountains of the moon, Saturn’s ring^ and Jupiter’s belts, have not ceased to occupy the attention of astronomers, though they are nightly to be seen for one penny on the Pont Neuf or on the Place Vendome and other open places. The public of the present day is too enlightened to confound together for one moment those who risk tbeir lives to gain a livelihood, and astronomers or meteorologists who run into danger in order to wrest from Nature some of her secrets!”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.