‘Gaudier’s life was a good example to show that art, which is simply exploiting to the full one’s natural gifts, is really bloody hard work, misery, momentary defeat and taking a lot of bloody stick’

1948: The young Ken Russell was intent on becoming a ballet dancer. He felt a desperate need to be creative but wasn’t quite sure how best to express it. He had a passion for music which led him to consider dance. He attended ballet classes four nights a week. He hoped ballet would become his career. But a knee injury meant he had to find work.

But what to do?

He considered his options. He was a practical man. He was good at making things. He could get a job in a factory. But one visit to the grey walled, red-bricked building, with its smoking chimney and the long line of workers clocking on, clocking-off, and Russell knew he could never do this: “I’d rather starve…”

And he did starve.

Then one day, Russell found a job as a guard at an art gallery. It gave him the money to pay for ballet classes and introduced him to the marvellous world of art and artists.

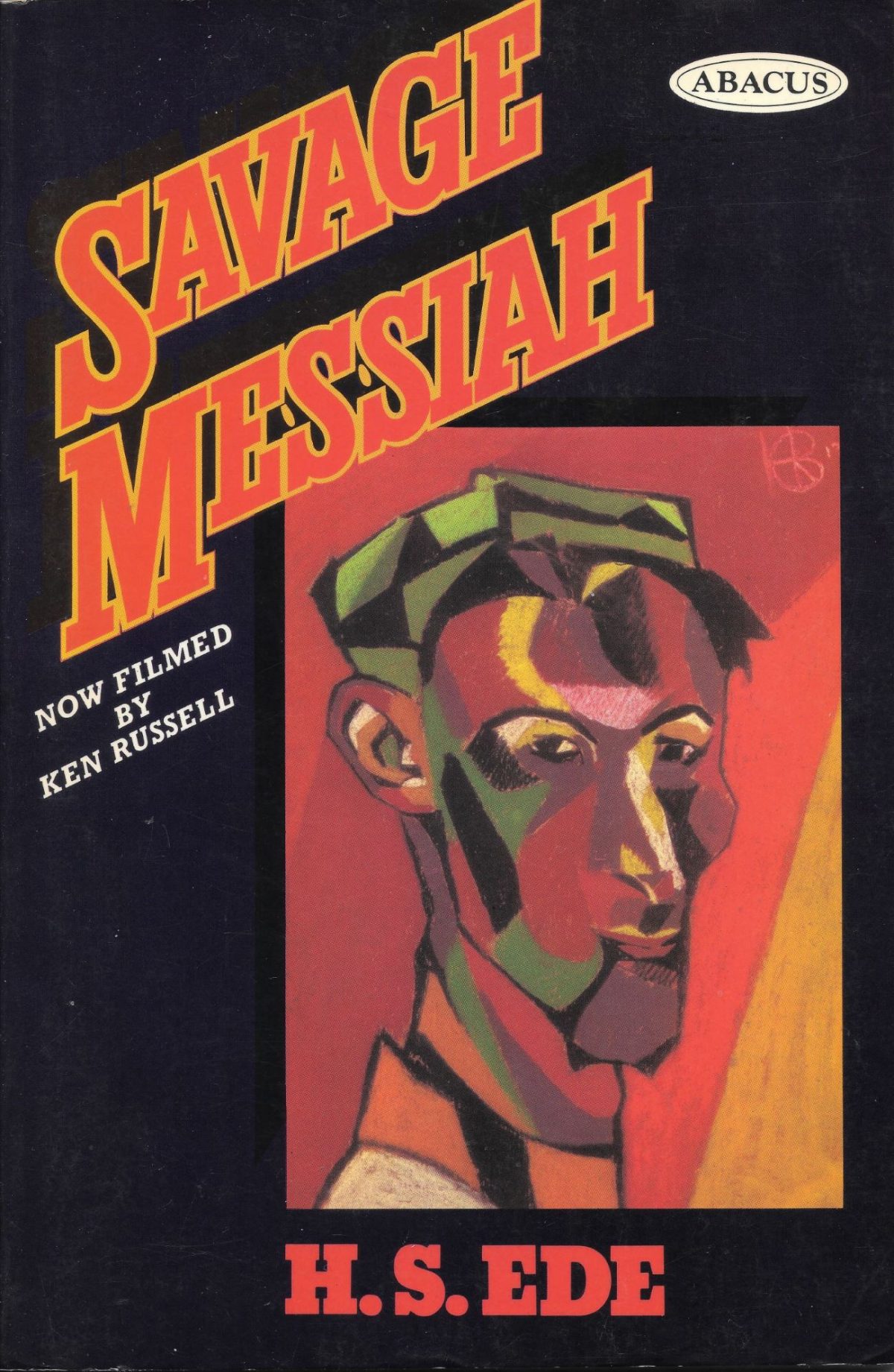

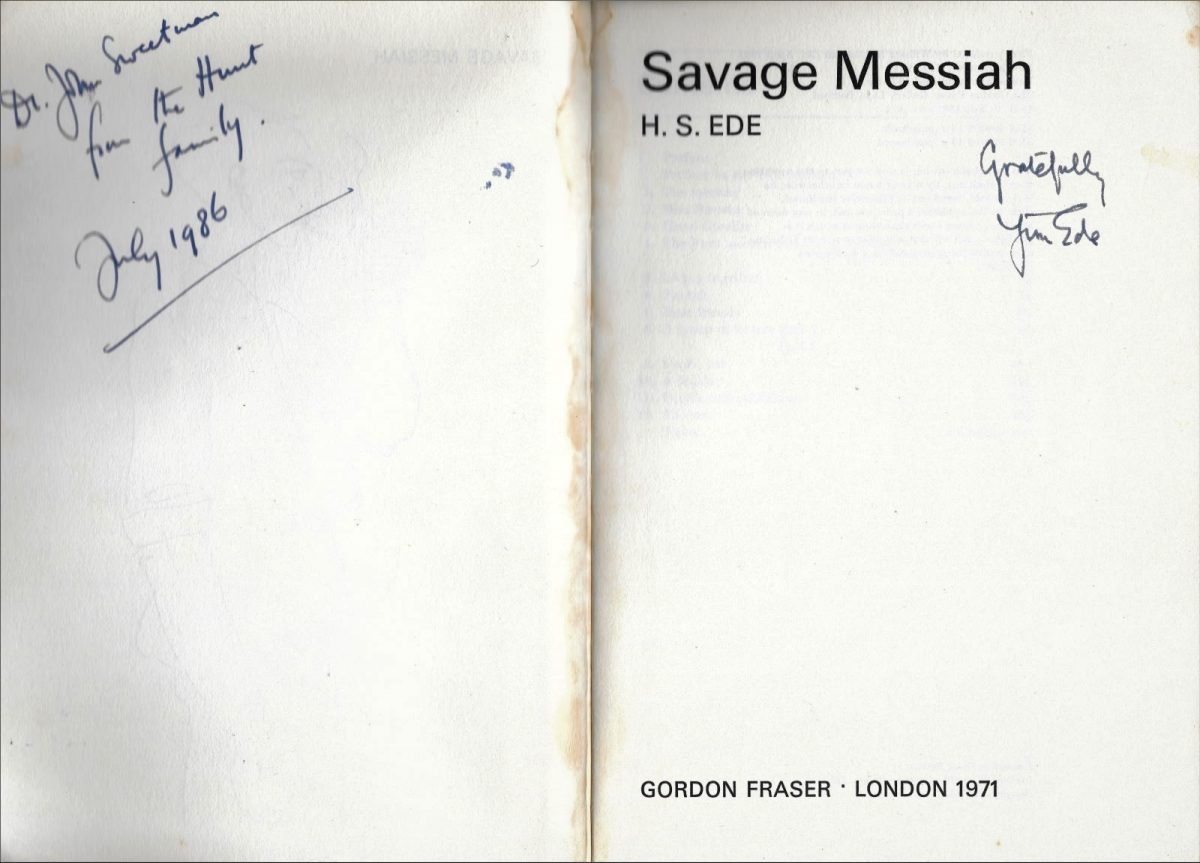

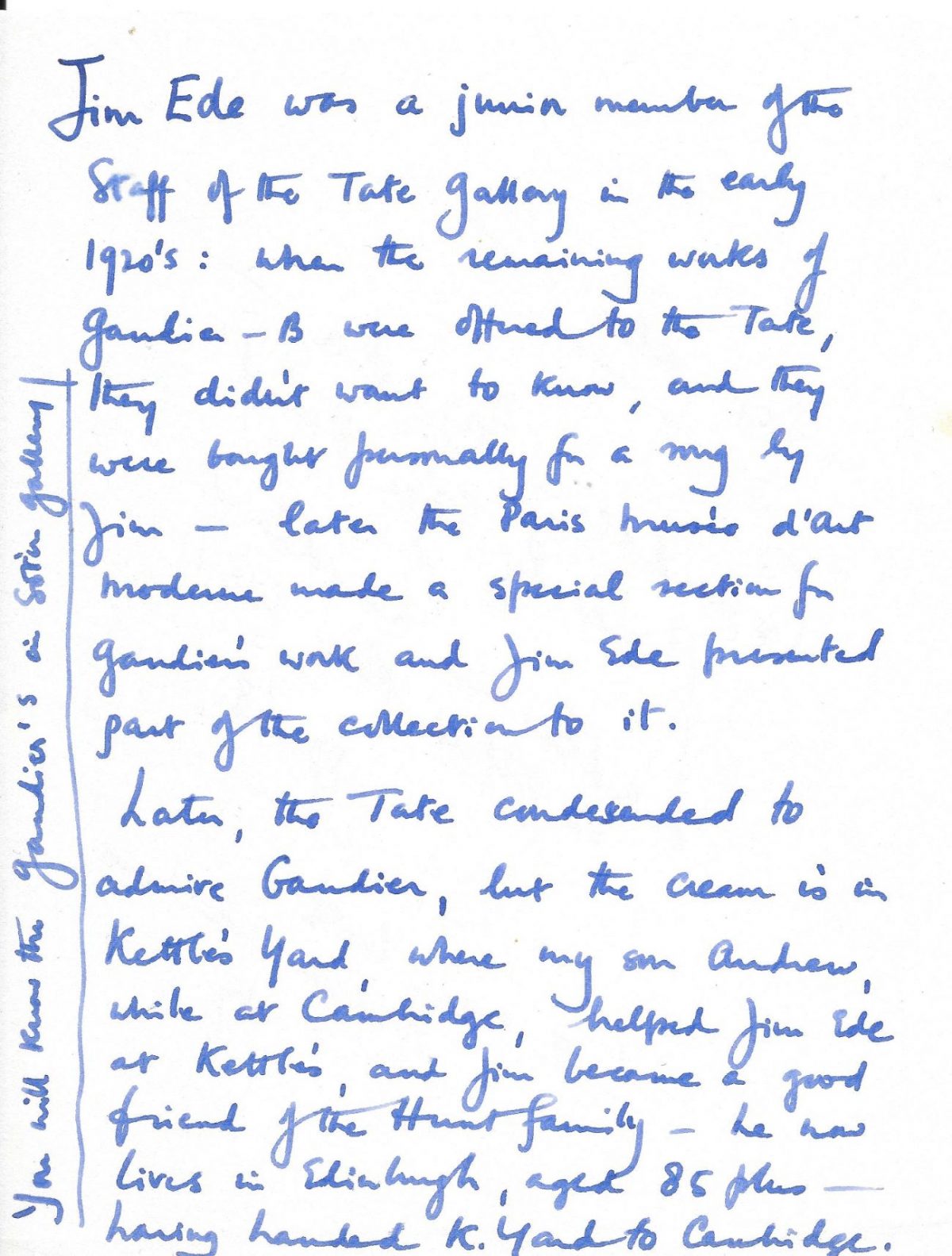

In his first week at Leferve Gallery, Russell saw paintings by Degas, Derain, Dali, Rousseau, Modigliani and Lowry. During his seventh month stint, Russell immersed himself in all of the art the gallery exhibited. It was a key moment in his development as a film director. Most importantly, he discovered the biography Savage Messiah by H. S. Ede which documented the lives of artist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and writer Sophie Brzeska. The couple lived in direst poverty but were devoted to each other and committed to their art. After some success in London, Gaudier-Brzeska was killed in action during the First World War in 1915. He was 23-years-of-age. Sophie Brzeska was destroyed by grief and eventually went mad. She was seen wandering the streets of London grieving for her lost boy.

The book consisted mainly of the letters between Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Sophie Brzeska. But Russell found the book inspirational:

I was impressed by Gaudier-Brzeska’s conviction that somehow or other there was a spark in the core of him that was personal to him, which was worth turning into something that could be appreciated by others. I wanted to find that spark in myself and exploit it for that reason.

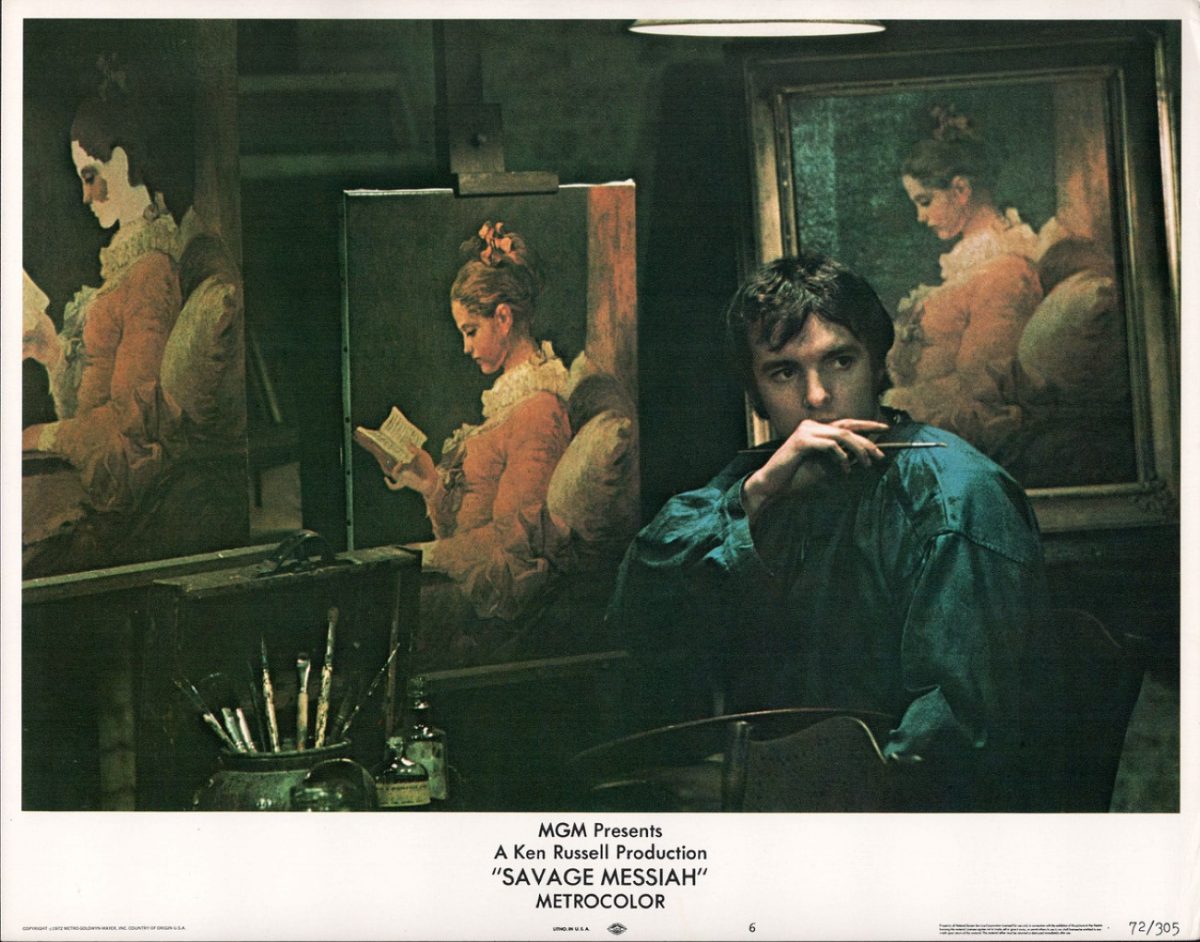

Henri Gaudier was born in 4th October 1891 to a carpenter father and a housewife mother. It was watching his father chisel, plain, and carve wood that inspired Gaudier to become a sculptor. As a child he showed considerable talent as an artist. He enrolled as a student, but learned more about art when he was employed as a copyist of classical paintings.

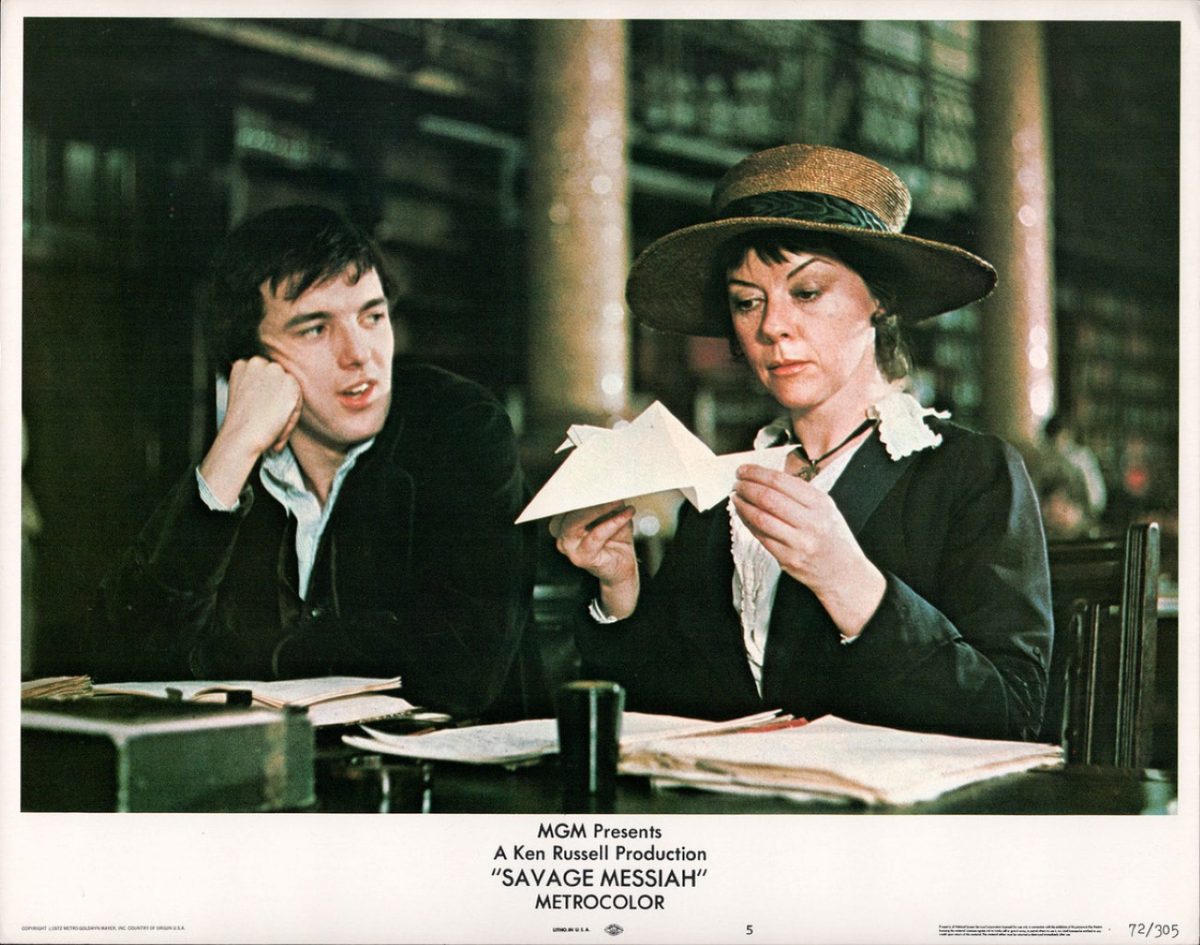

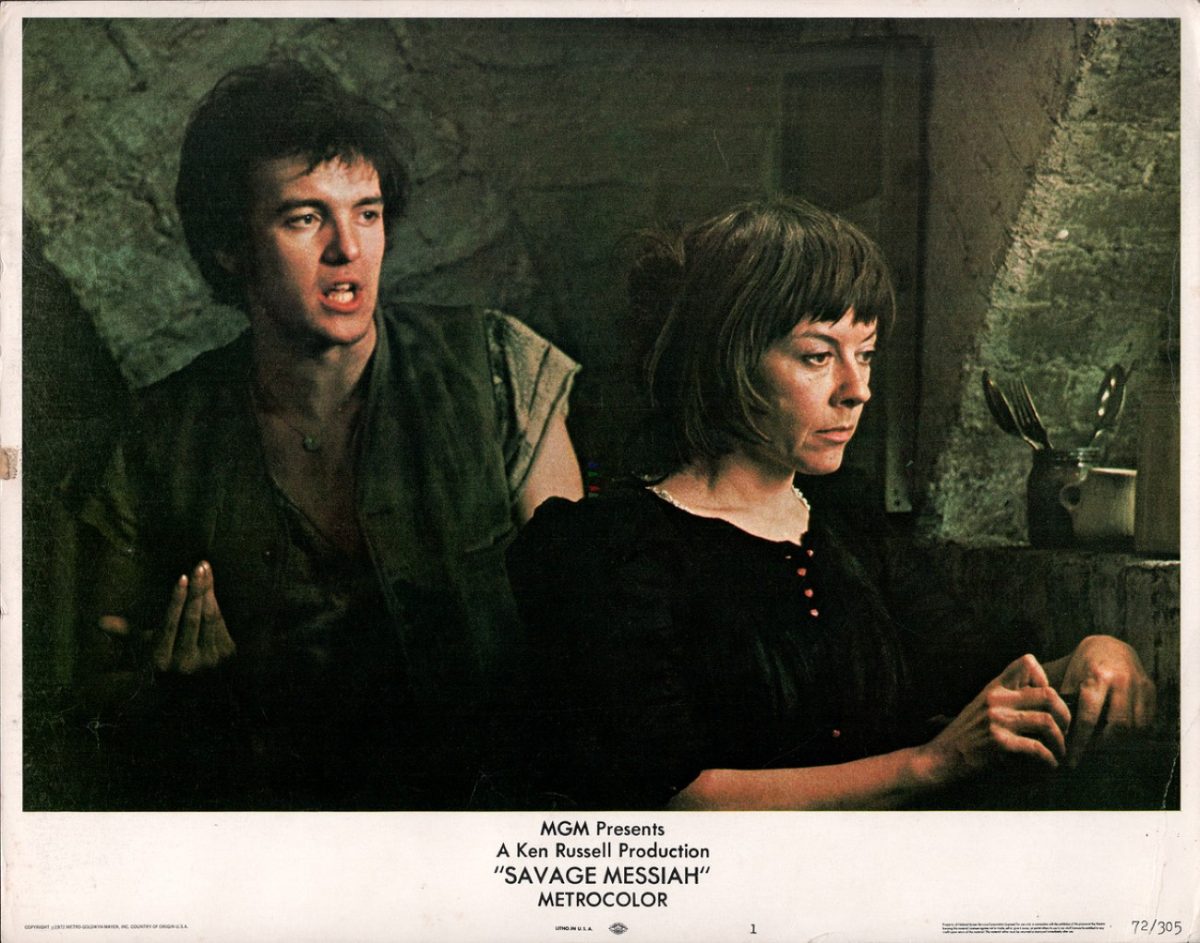

In 1909, Gaudier met Sophie Brzeska, a writer who aspired to publish her autobiography Matka. Brzeska was a governess. She was twice Gaudier’s age. Her life until their meeting had been one of misery and heartbreak–a tale of so horrendous no Gothic author could have ever imagined it.

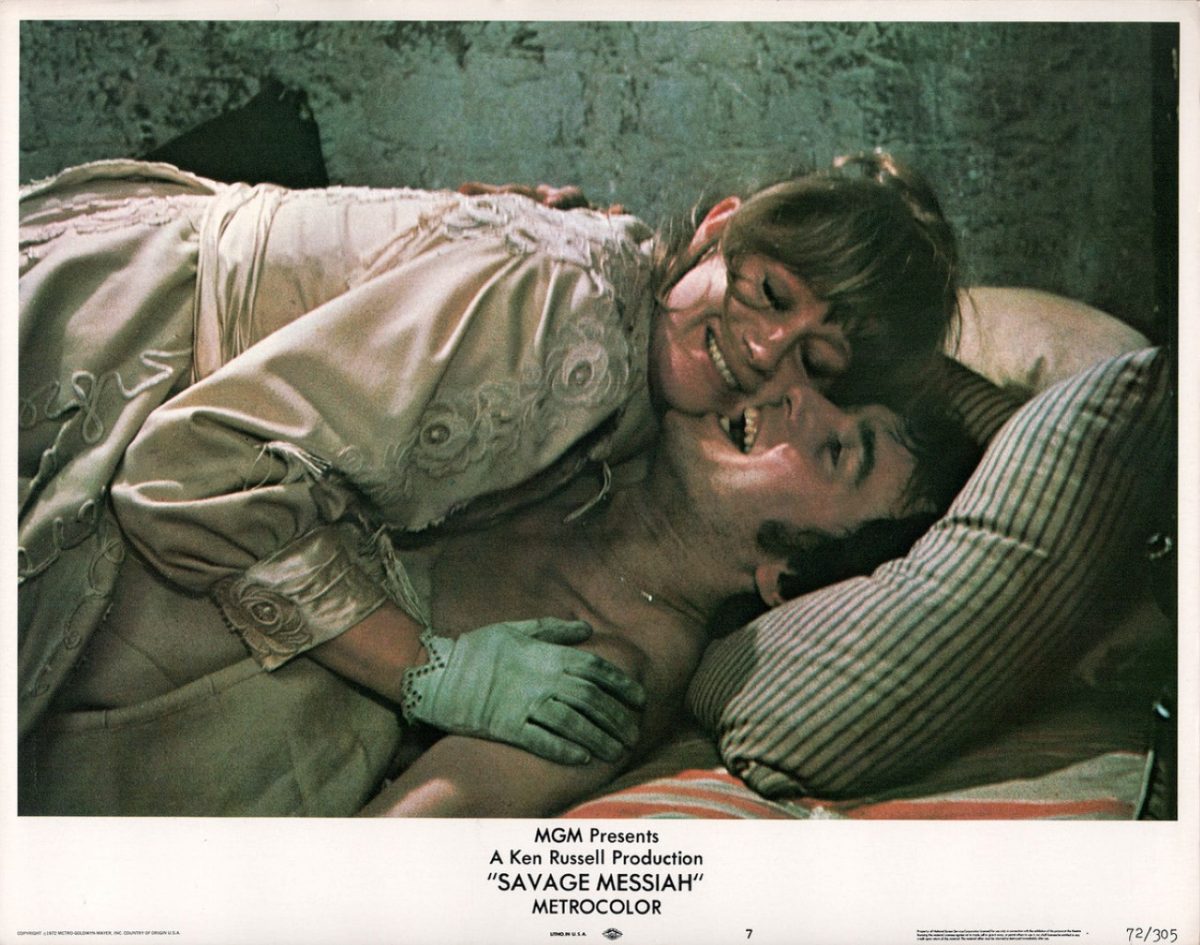

Henri met Sophie in a library. Their attraction was immediate. They stayed together for the next five years. Gaudier’s parents were shocked by their son’s relationship with a much-older woman and banned them from their house. In 1910, Henri and Sophie fled to London were they lived and worked for next five years.

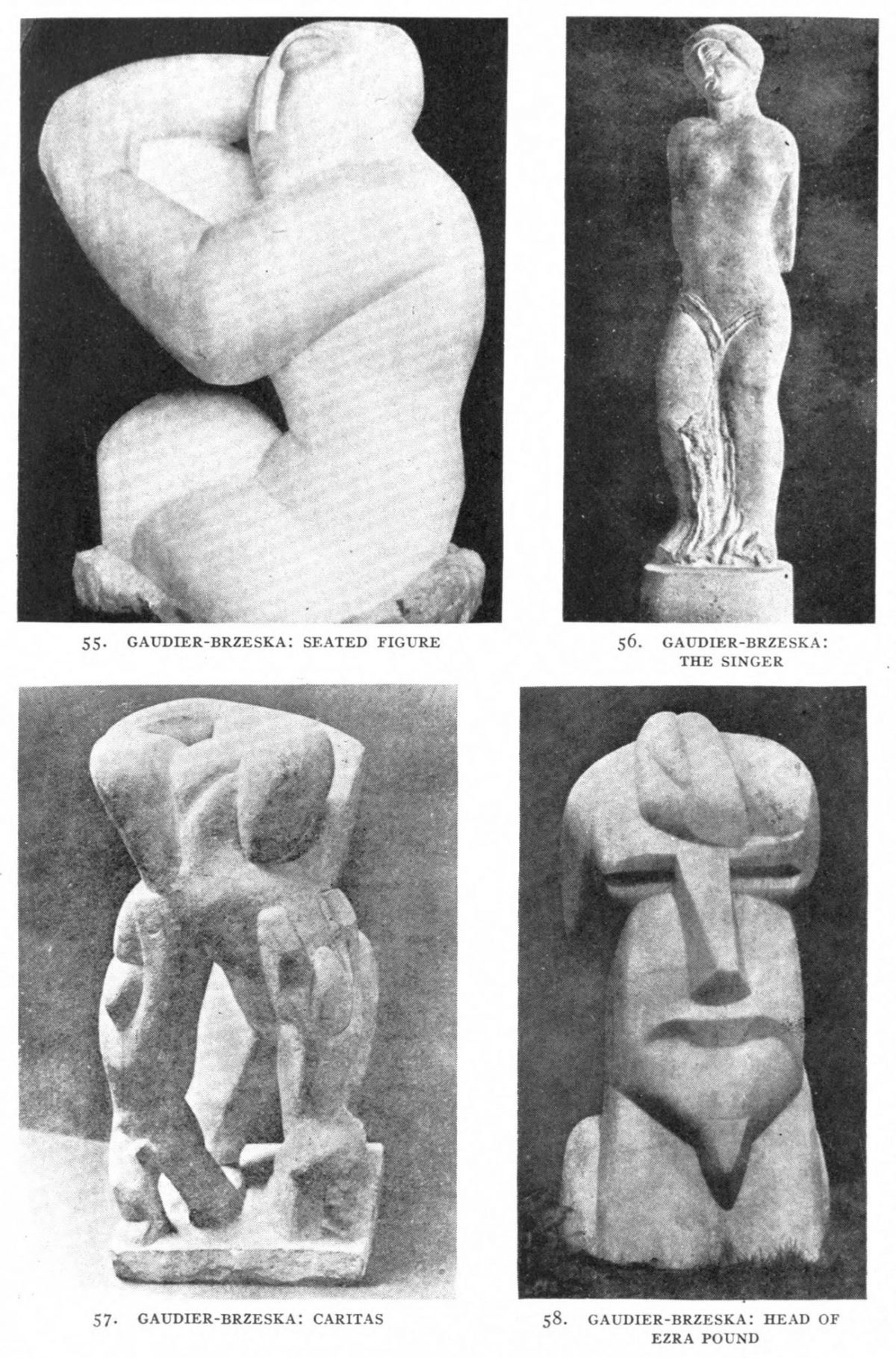

Gaudier worked by day and sculpted by night. Sophie wrote by day and looked after Henri. In London, the couple met and mixed with Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis, and Edward Wadsworth. This small group loosely formed the short-lived Vorticist group. It was through his association with Vorticism that Gaudier-Brzeska formed his own ground-breaking maxims about sculpture, which he published in the Vorticist magazine Blast:

Sculptural feeling is the appreciation of masses in relation.

Sculptural ability is the defining of these masses by planes.

Henri attempted a “complete revaluation of [sculptural] form as a means of expression.”

As Henri flourished, Sophie weakened. In 1914, while Sophie recuperated at a hospital outside London, Henri enlisted in the French army. They never saw each other again:

….after months of fighting and two promotions for gallantry, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska was killed in a charge at Neauville St. Vaast, on June 5th, 1915.

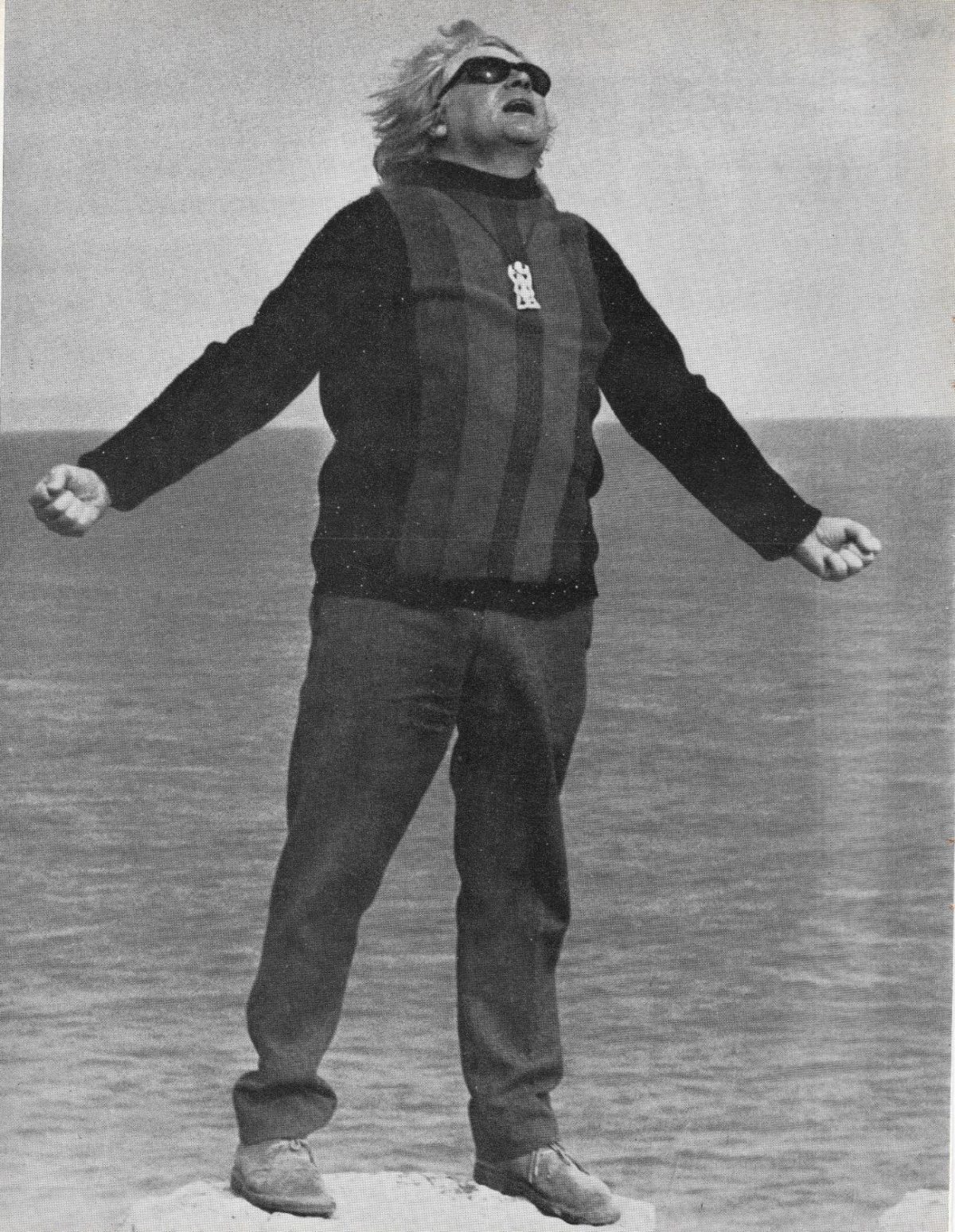

Russell kept the story of Gaudier-Brzeska close. At his lowest ebb, it inspired him to believe in his talents and to keep on going. His career as a ballet dancer faltered. He became a photographer and established a highly successful career. This led Russell to his making short films, which in turn brought him to the attention of Huw Wheldon at the BBC. Wheldon hired Russell as a director for his arts series Monitor. During his ten-year stint at the BBC, Russell wrote and directed some of the greatest arts documentaries ever made. He gained international recognition and began directing movies French Dressing and The Billion Dollar Brain. It was his third movie Women in Love that established Russell as one of the world’s greatest directors.

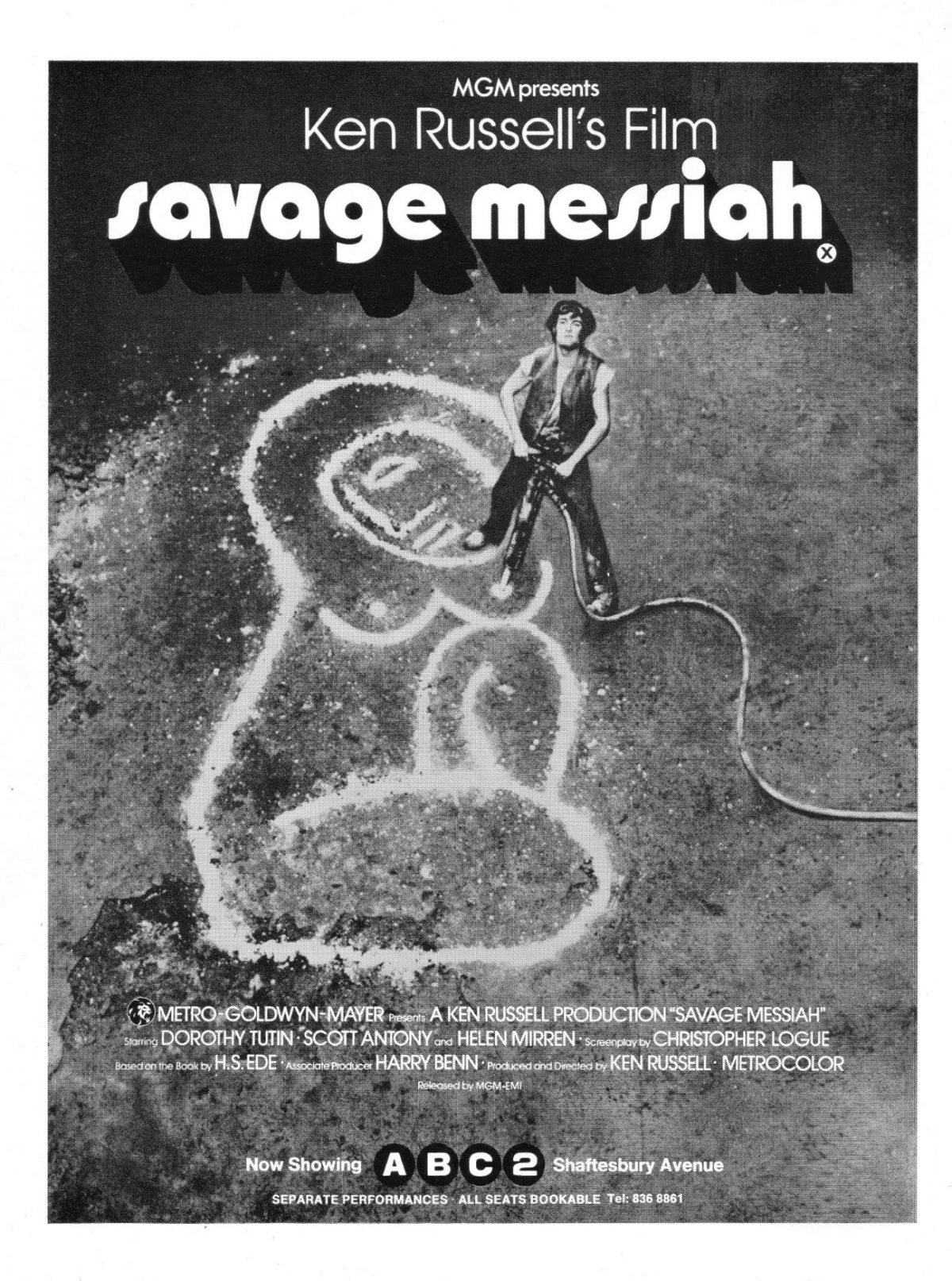

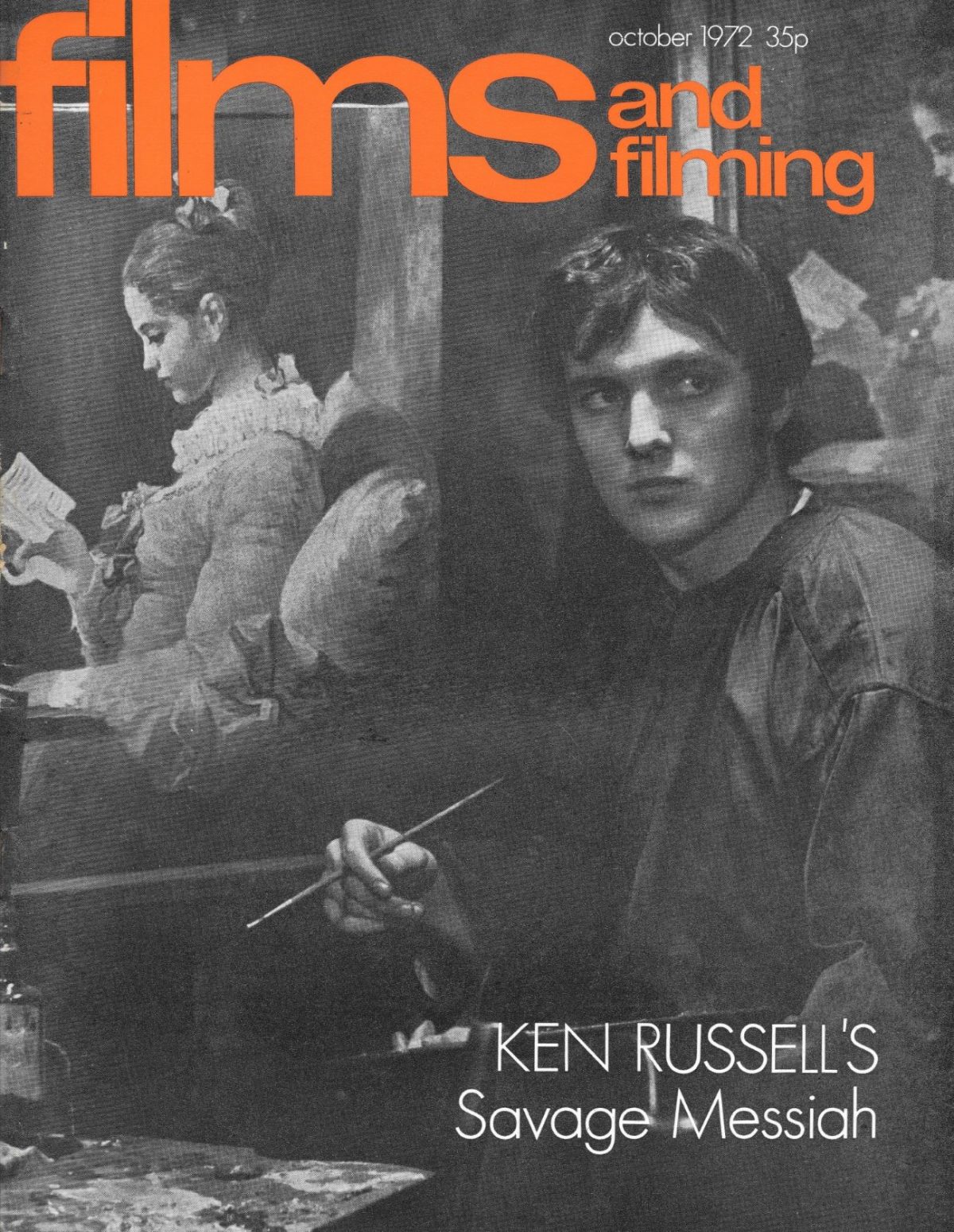

In 1971, Russell directed three of his most successful films: The Music Lovers, The Devils and The Boyfriend. He was now rich and successful enough to pay back the debt he felt he owed to Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Sophie Brzeska. He optioned Ede’s book, worked on a script with poet Christopher Logue, and paid out of his own pocket for a movie version of Savage Messiah.

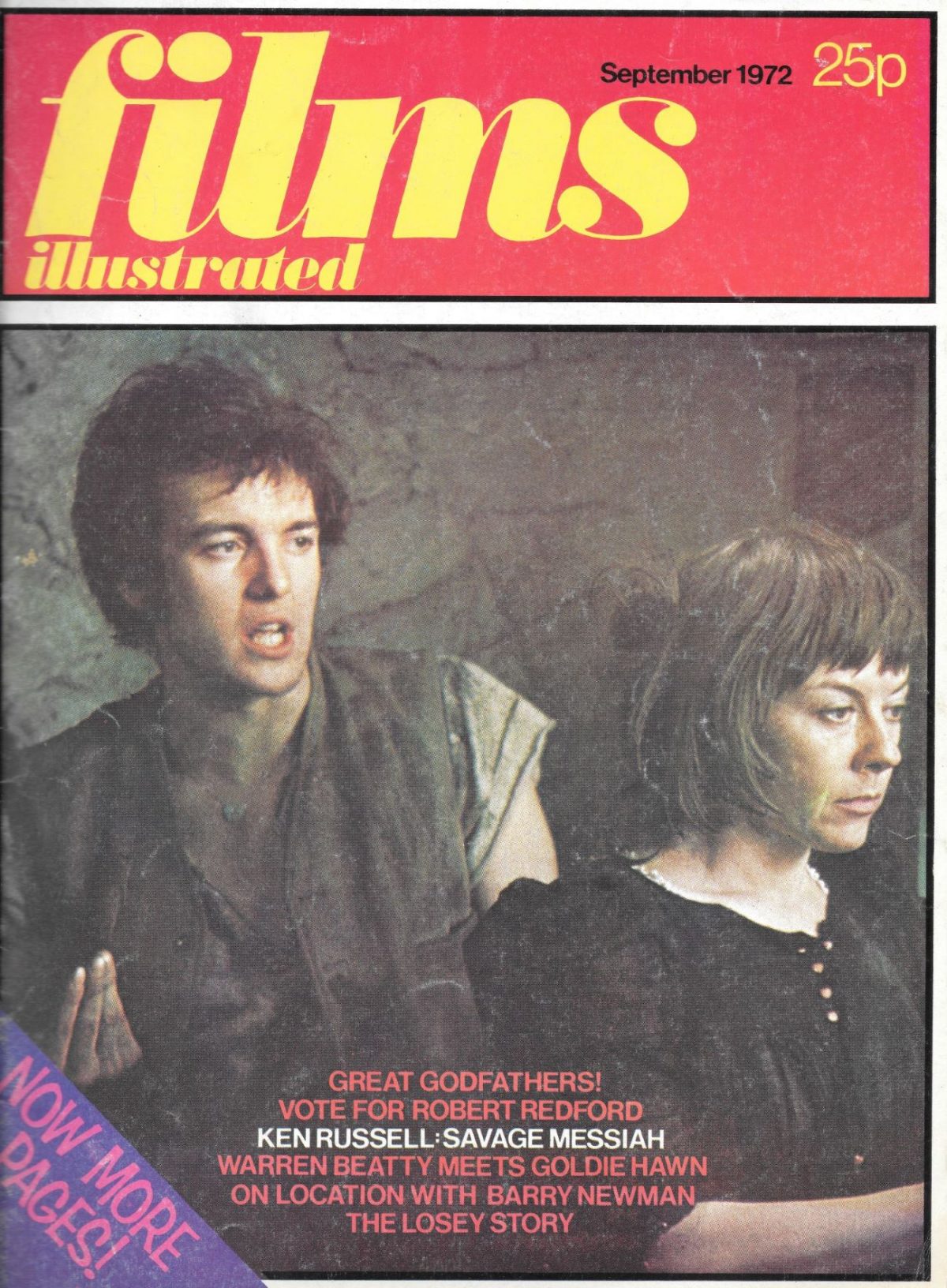

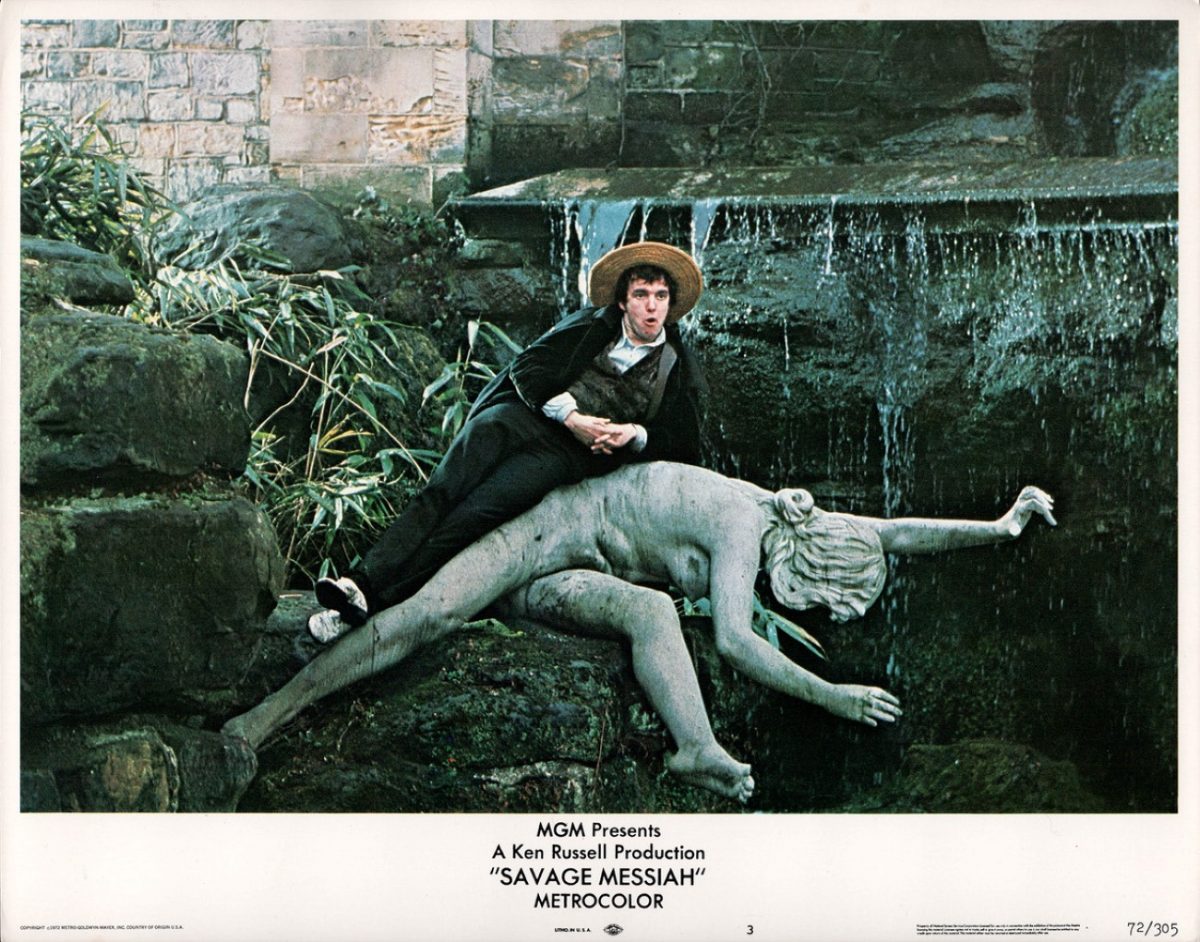

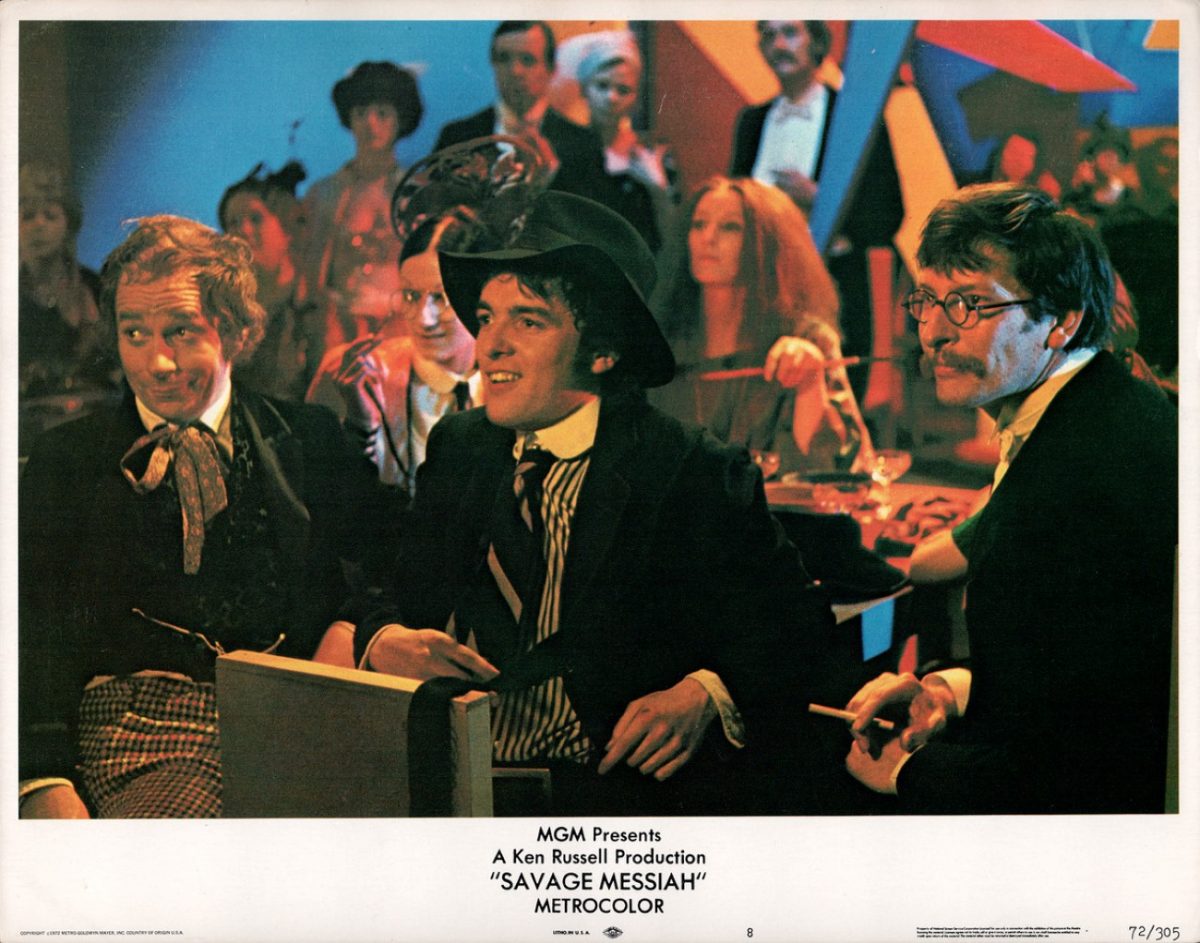

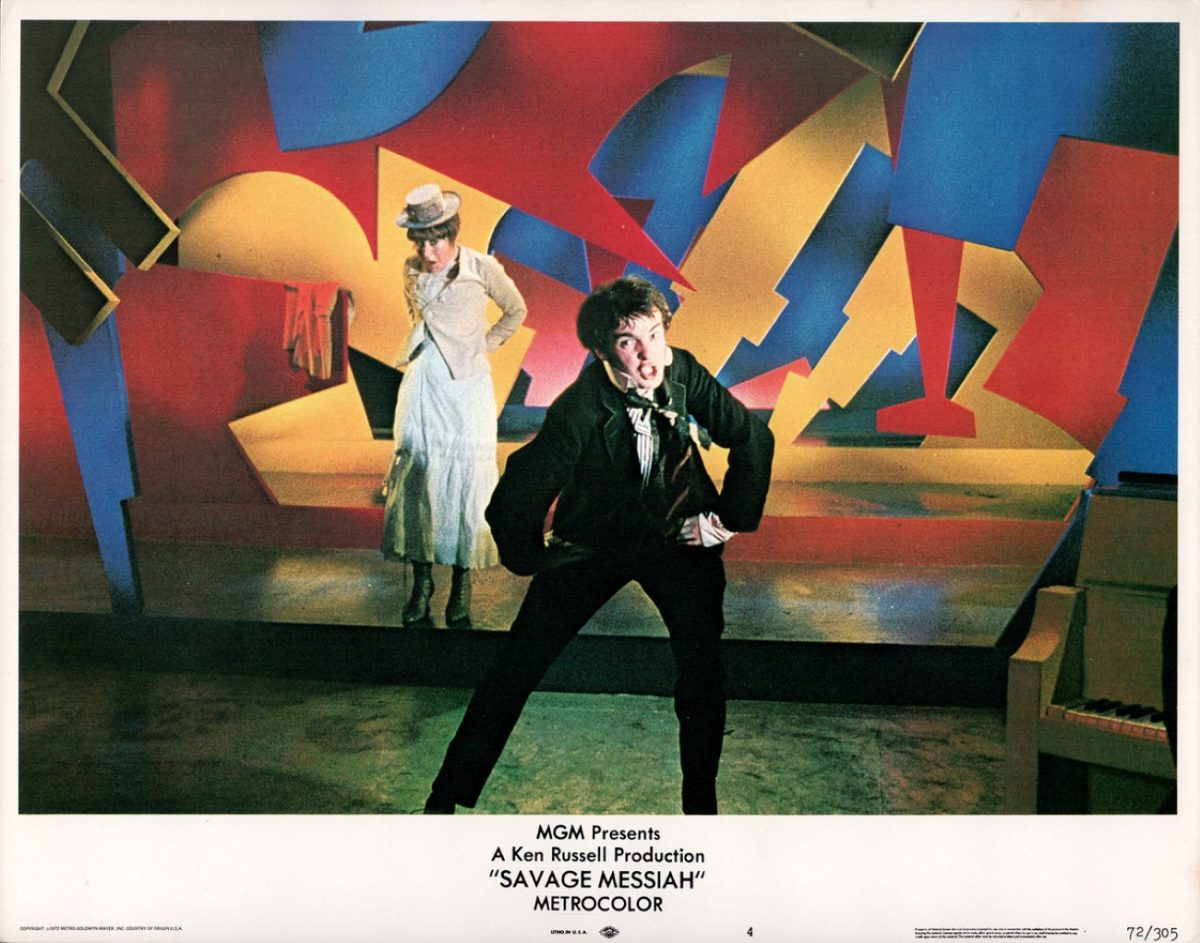

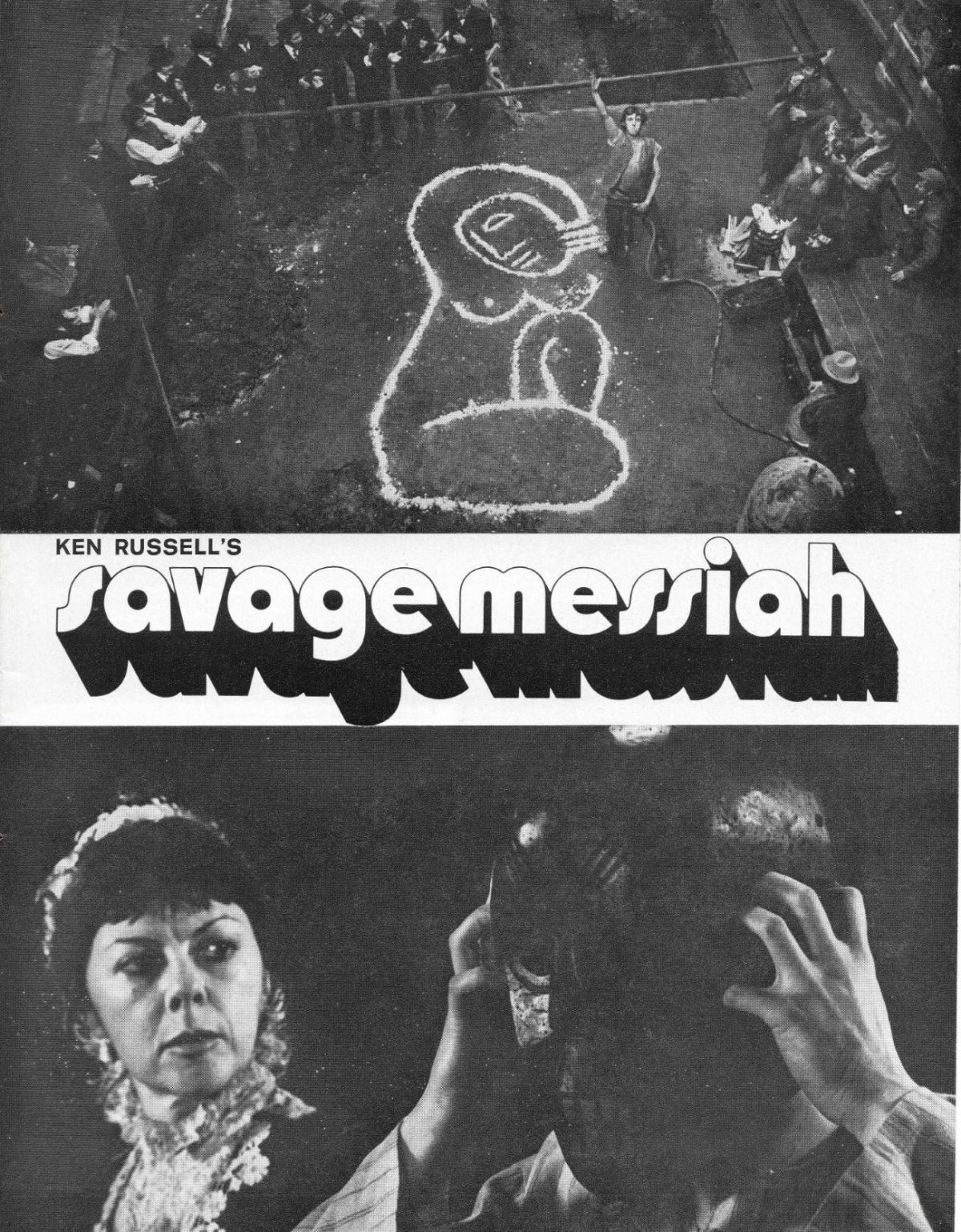

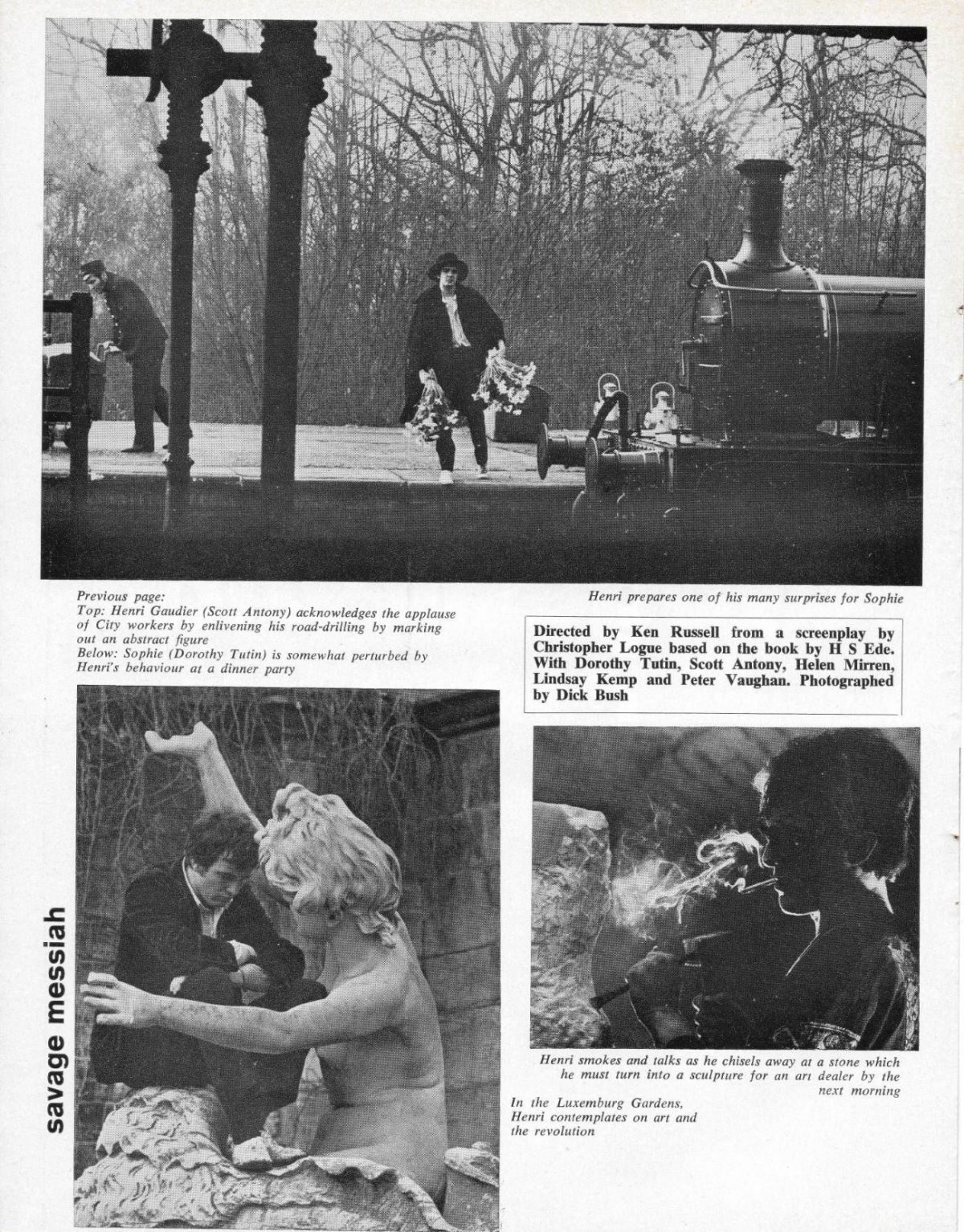

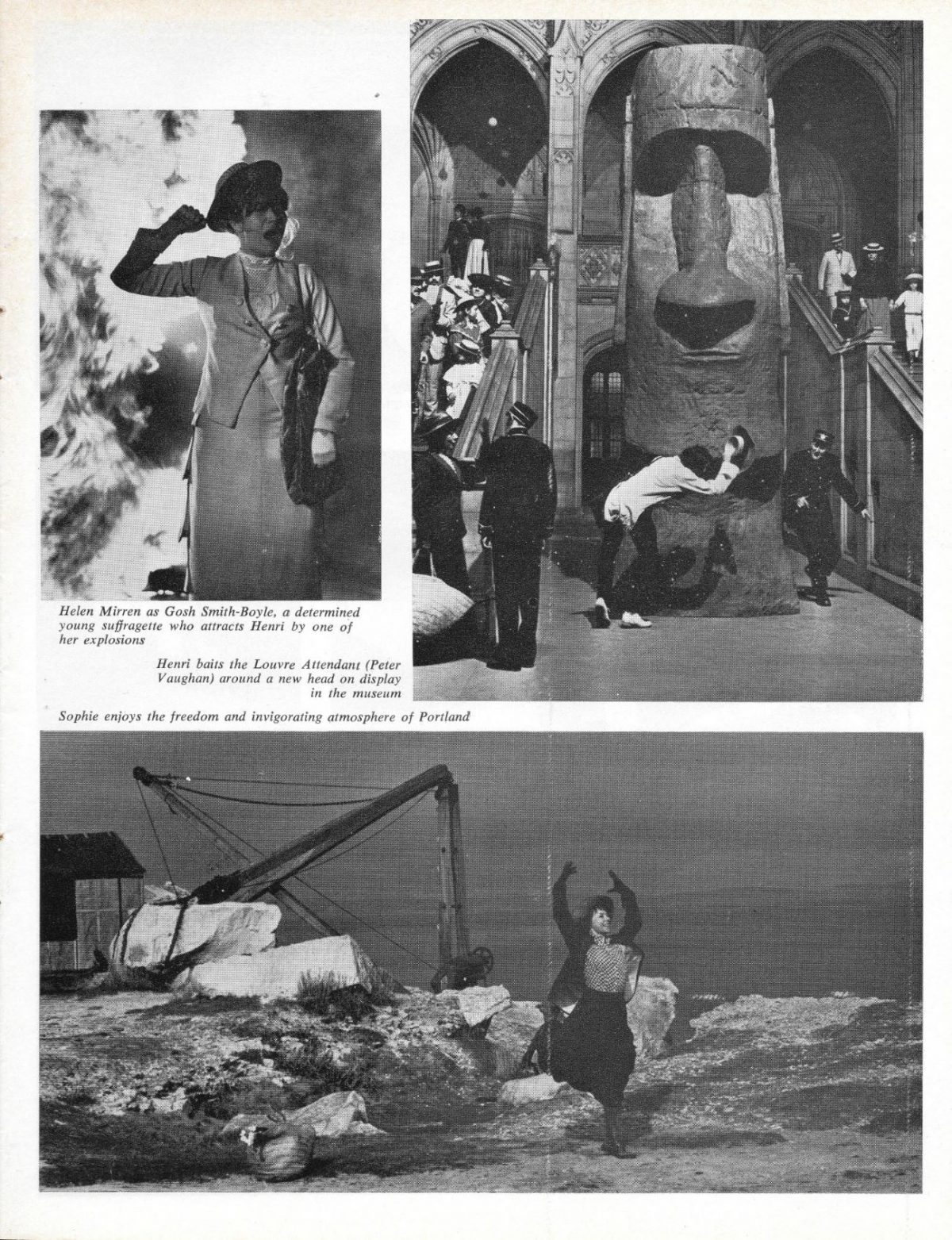

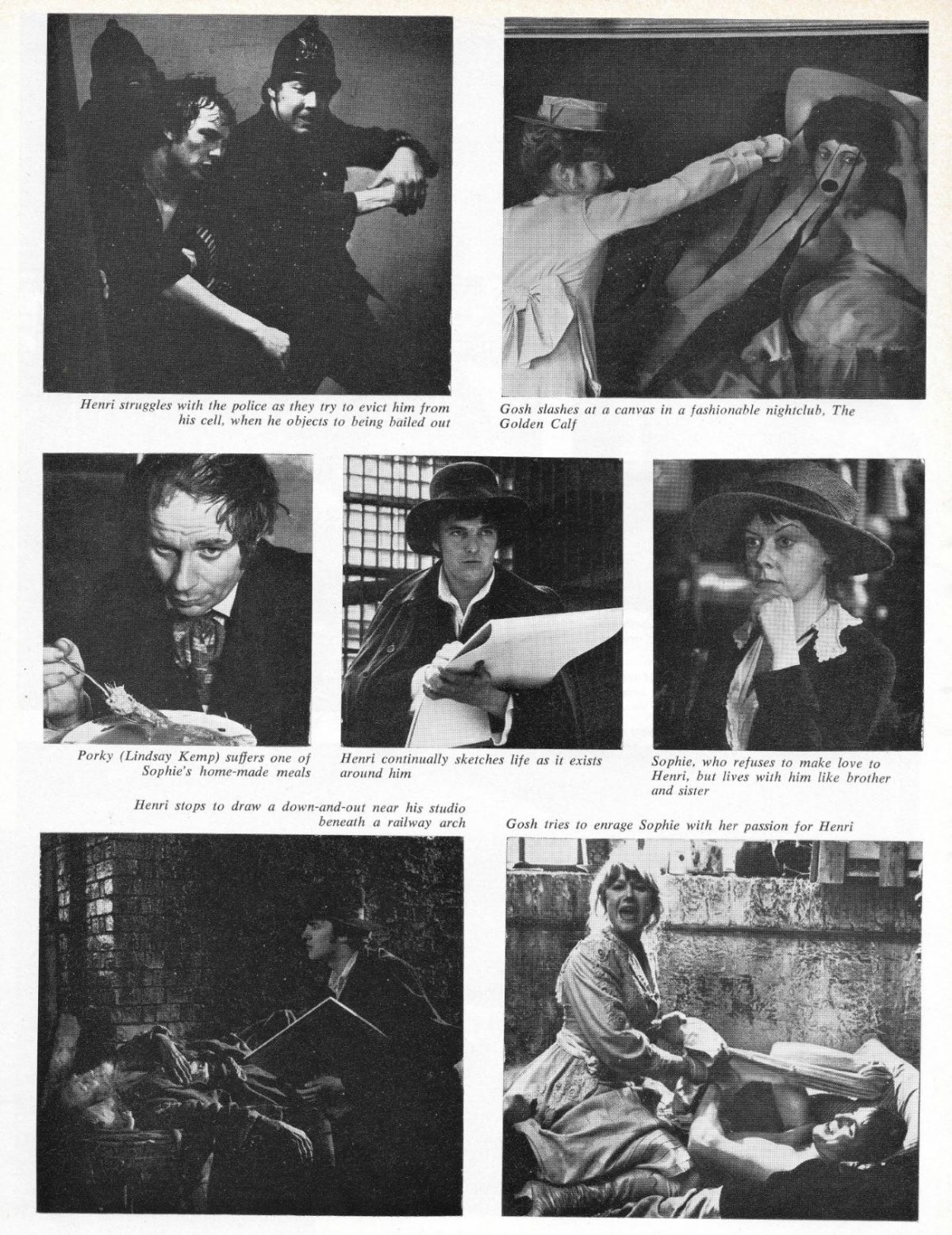

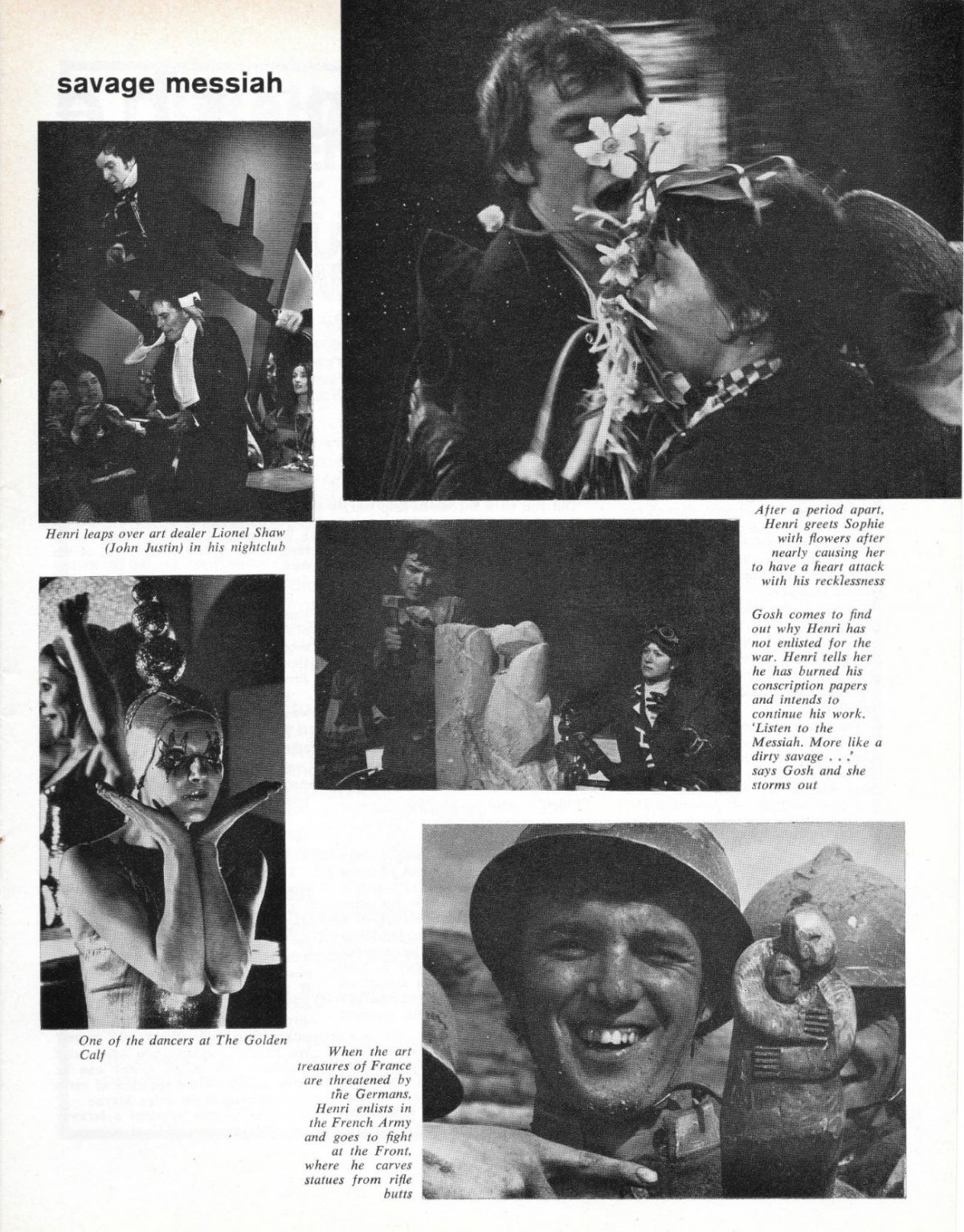

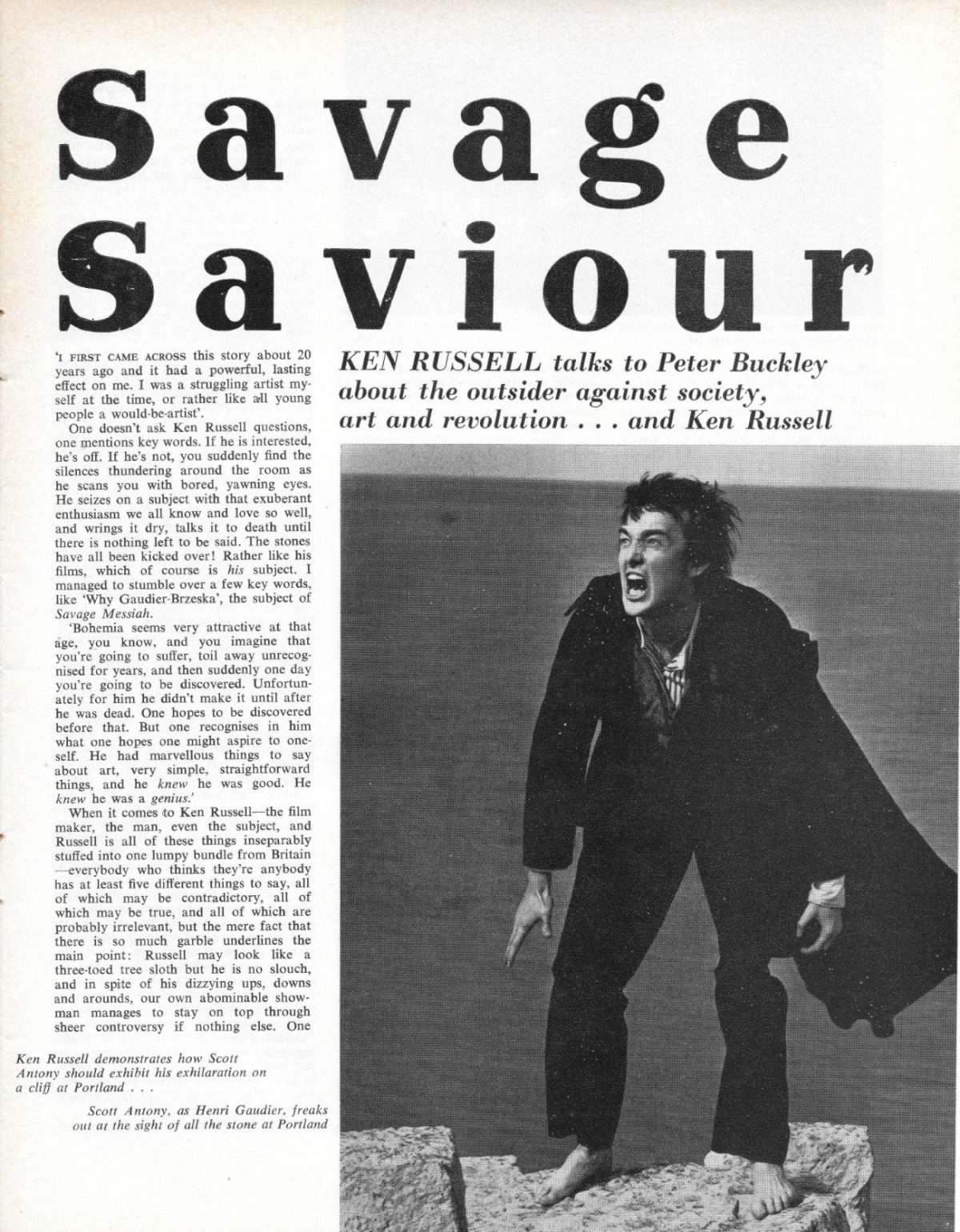

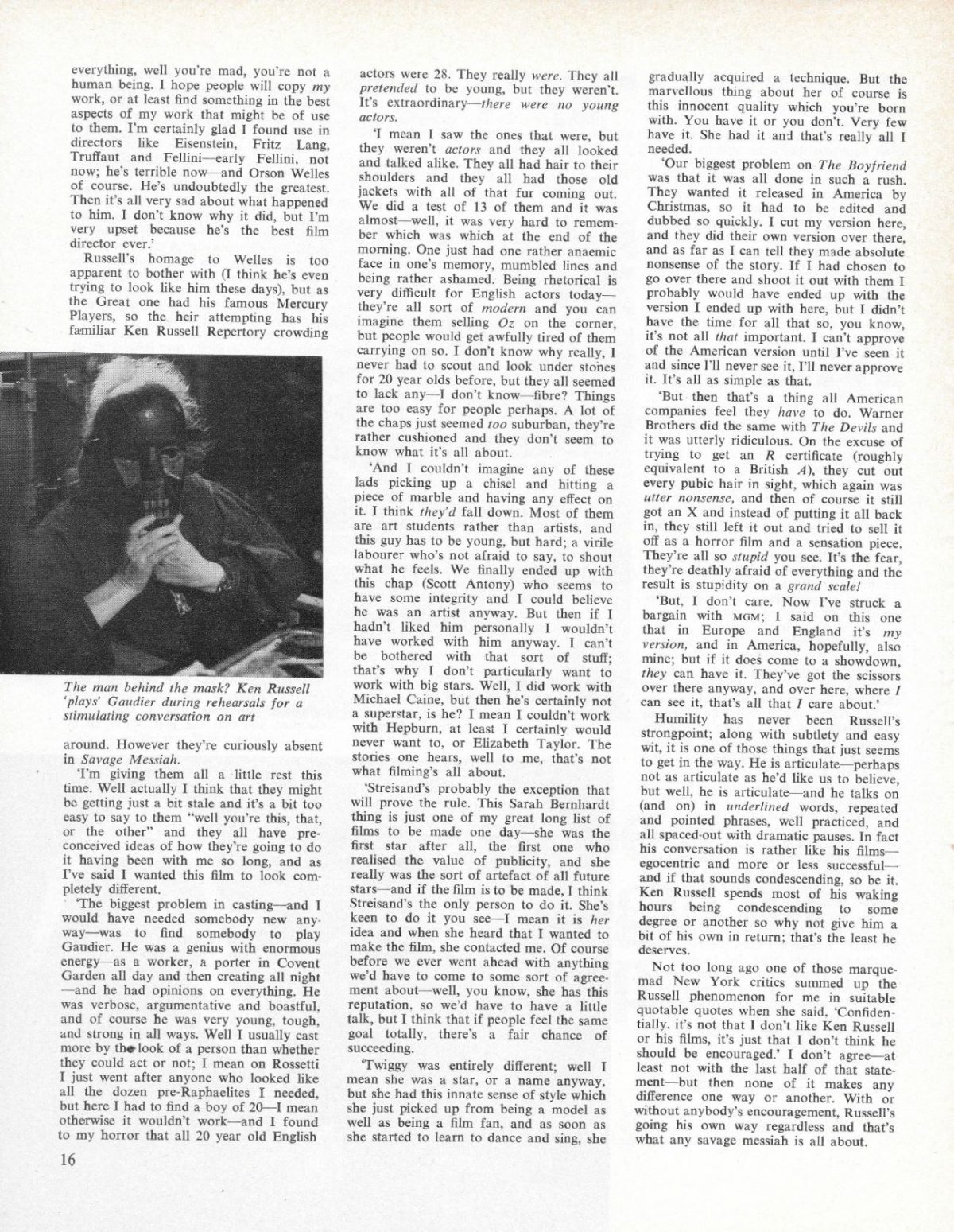

The film was low-key. A chamber piece compared to the symphonies of Women in Love, The Music Lovers or The Devils. Russell brought in a young unknown actor Scott Anthony to Gaudier-Brzeska. He eschewed any established performers as they would only bring a preconceived notion of what an artist should be like–dandies with long hair and velvet jackets. Dorothy Tutin was cast as Sophie Brzeska. The dancer Lindsay Kemp played Angus Corky. The set designs and artworks were created by Derek Jarman and Christopher Hibbs. Jarman later recounted how their copies of Gaudier-Brzeska’s drawings made their way to auction rooms were they were sold as the genuine item. Shirley Russell designed the costumes.

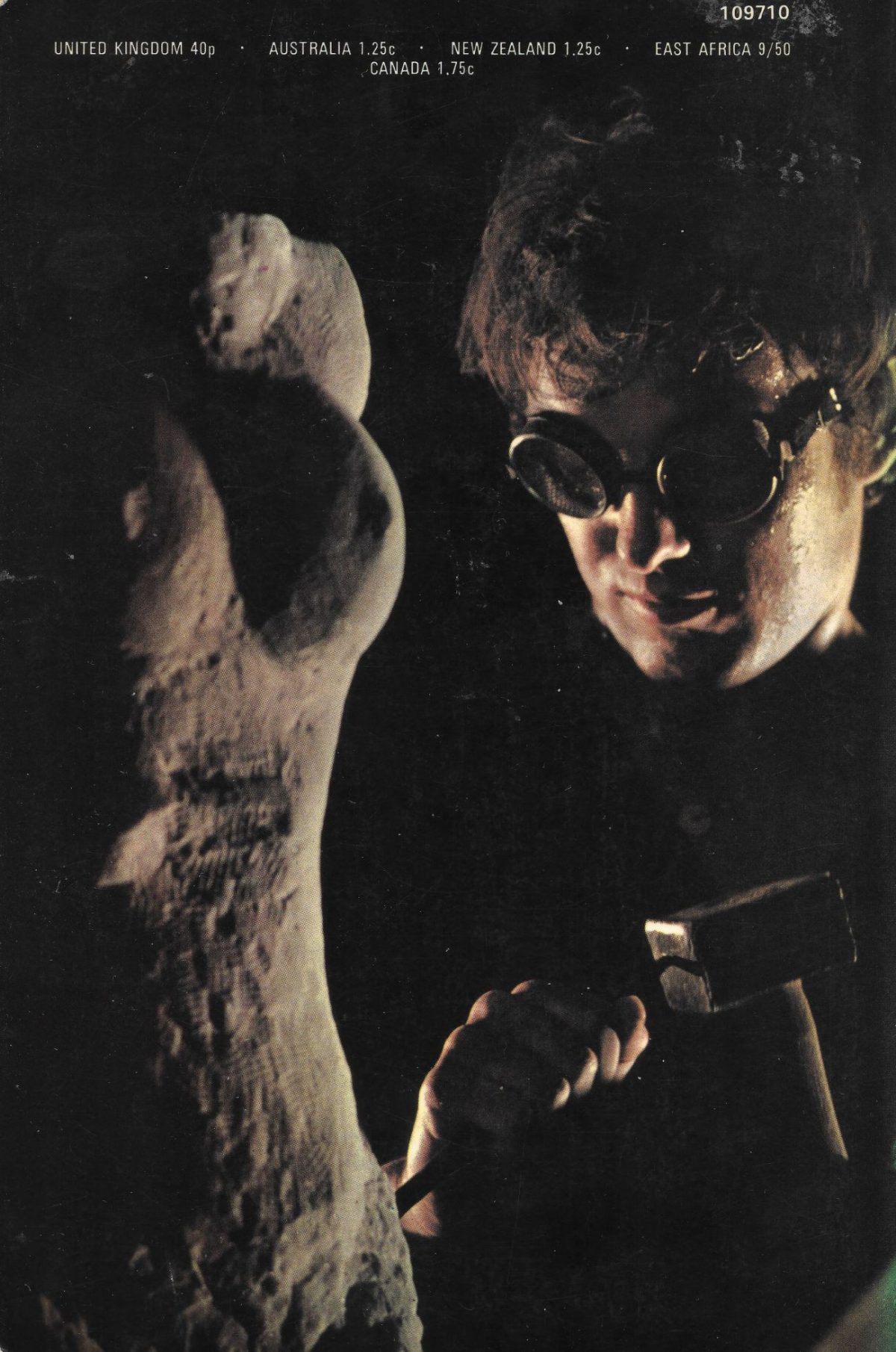

Savage Messiah proved as strong a touchstone to a younger generation as Ede’s biography had been to Russell. In one key scene, Gaudier-Brzeska braged to an art dealer he has a major new sculpture in his studio. The dealer says he will come visit tomorrow. Of course, Gaudier-Brzeska has no such statue. With the help of Corky, he steals a marble headstone from a cemetery. He then sculpts a marble torso throughout the whole of the night. The following day, the dealer fails to visit. Gaudier-Brzeska takes his statue and throws it through the dealer’s gallery window. as Russell explained:

Gaudier’s life was a good example to show that art, which is simply exploiting to the full one’s natural gifts, is really bloody hard work, misery, momentary defeat and taking a lot of bloody stick – and giving it… If you really want to show the hard work behind a work of art, then a sculptor is your best subject. I was very conscious of this in the sequence when Gaudier sculpts a statue all through the night. It’s the heart the core of the film, the most important scene to me.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.