The Centre Point office block in central London, as seen from Denmark Street, 24th August 1966. The White Lion pub stands to the right. (Photo by Philips/Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Last year it was reported that an apartment in Centre Point had probably become, at £5 million, the most expensive student flat in the world. A snip, however, compared to the penthouse at the top which was on the market for £55 million.

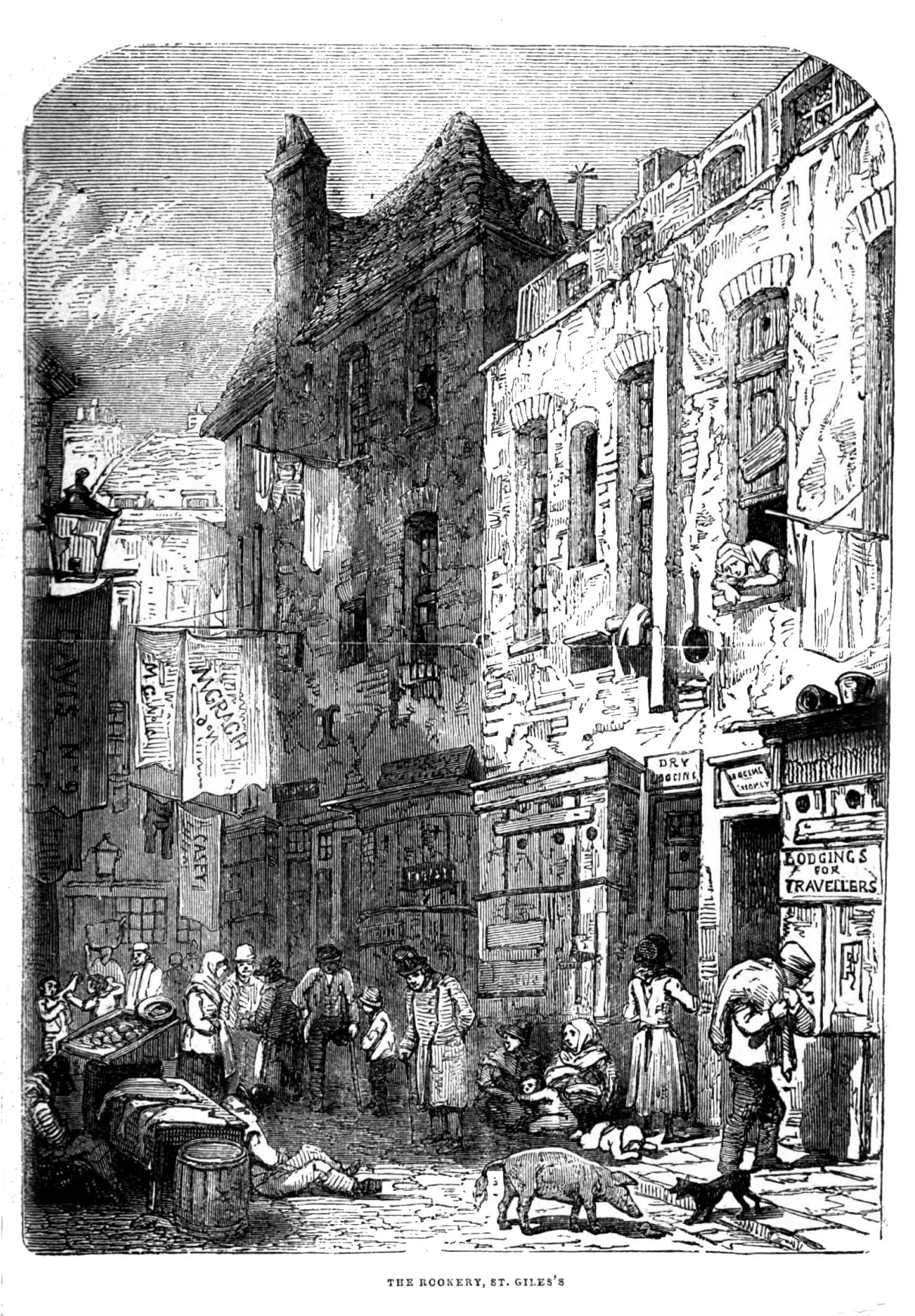

Centre Point was built on the edge of an area known as St Giles. A part of London immortalised by Hogarth’s Gin Lane (in 1750 over a quarter of all residences in St Giles’ parish in London were gin shops) and the location of the worst of the London ‘Rookeries’. Peter Ackroyd in London: A Biography wrote that “the Rookeries embodied the worst living conditions in all of London’s history; this was the lowest point which human beings could reach”. By the 19th century St Giles’s was possibly the worst slum in Britain with open sewers running through rooms and cess pits left untended. Fifty-four residents wrote a letter to the Times in July 1849 under the headline “A Sanitary Remonstrance”: “We live in muck and filth. We aint got no priviz, no dust bins, no drains, no water-splies, and no drain or suer in the hole place.”

St Giles Rookery 1953

The beginning of the end for the infamous St Giles rookery came in 1847 when New Oxford Street, part of major slum clearing, was driven through the parish to join Oxford Street with Holborn. Just over a hundred years later it was the congestion at the junction of New Oxford Street with Tottenham Court Road (known as St Giles’ Circus) which, indirectly, brought us Centre Point – a building that came to symbolise the greed and rapacity of the post-war property boom even before it was built.

A few years of World War Two and to help with the increasing traffic flow London County Council wanted to build a roundabout at St Giles’s Circus and also ‘rationalise’ the surrounding area. The council, however, was only allowed to offer compensation at pre-war values which meant that no one was willing to sell to them. In 1959 the developer Harry Hyams, via the architect Richard Siefert, let it be known that he could buy the land for the roundabout if the LCC would agree to planning permission to build around and over the top of it. It was thought by the council that this could be a relatively simple way to solve a rather complicated problem and they agreed.

After running rings around a confused LCC, the pipe-smoking Colonel Richard Siefert, along with the structural engineer Wilhelm Frischmann (father of Elastica’s Justine) were somehow allowed to create a building of an unprecedented 34 storeys. Centre Point became London’s first bone-fide skyscraper. It’s been said that Seifert, designer of over 500 buildings, did more to alter the London skyline than any architect since Sir Christopher Wren.

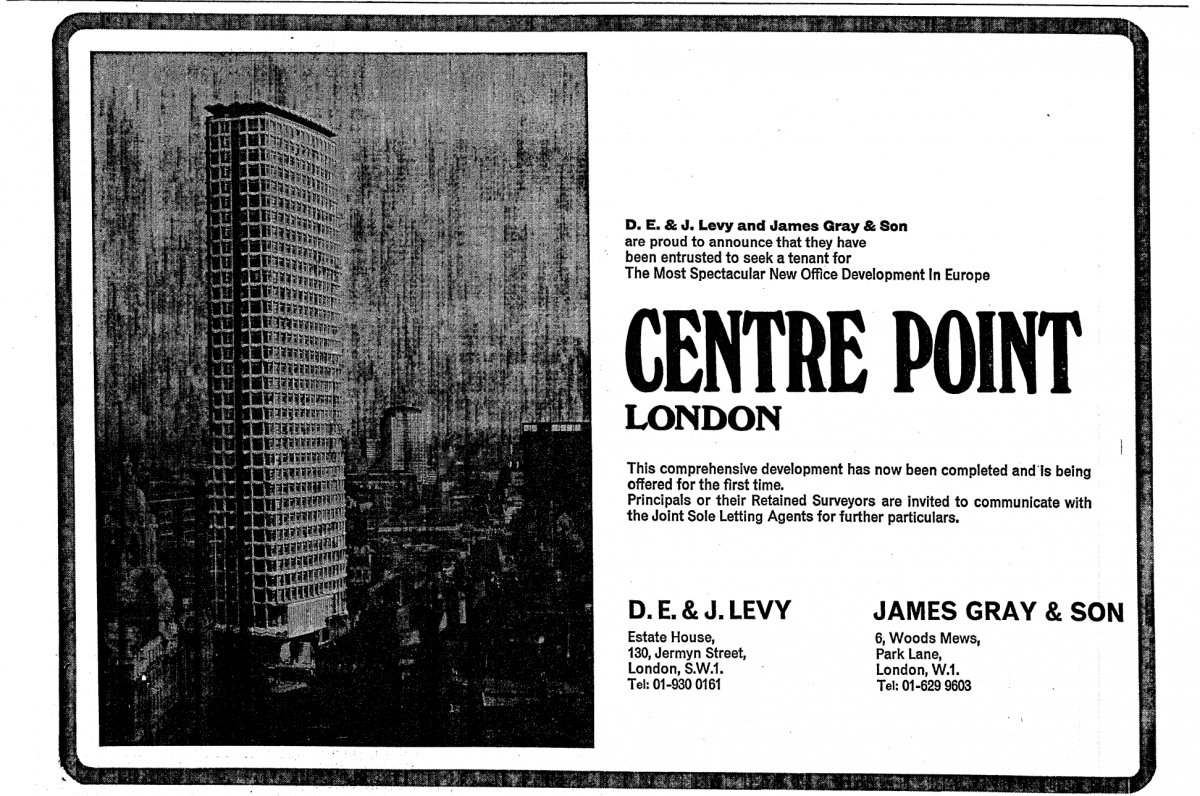

Centre Point ad from 1968

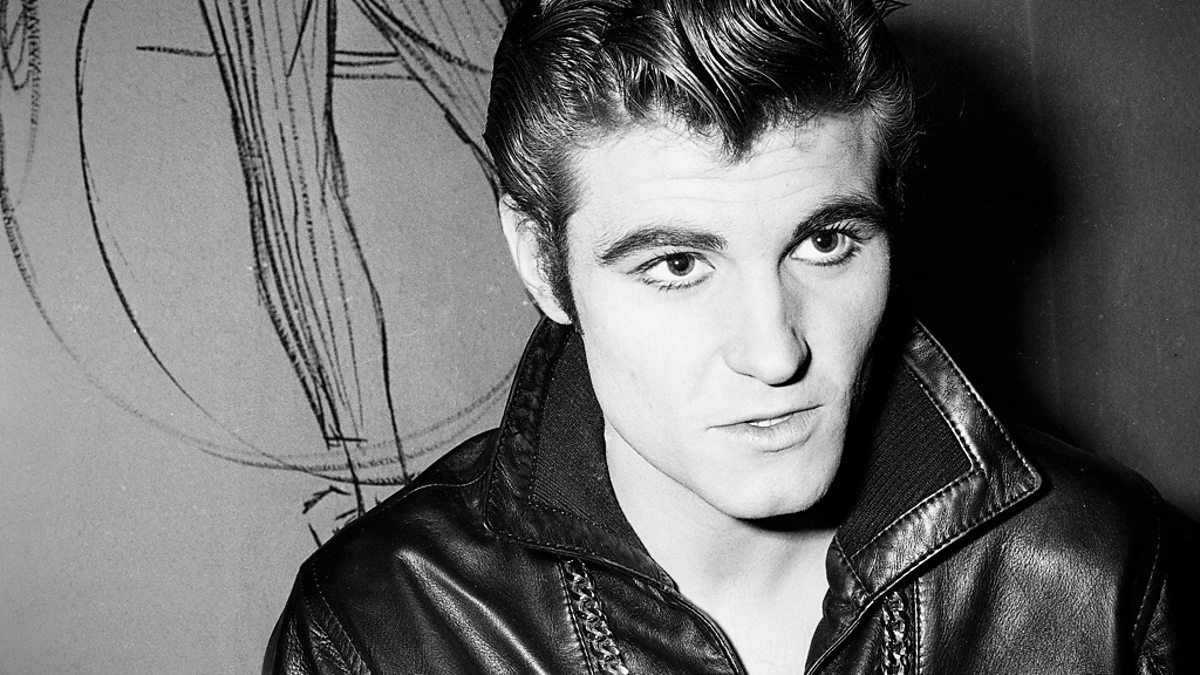

Charlotte Rampling by Lewis Morley, resin print, 1960s

The building’s construction began in 1963 and was completed three years later. Although, controversially, it remained empty for years with Hyams insisting he would only commit to what he called “a single tenant on undoubted covenant”. In reality, at a time of rapidly increasing property prices, Hyams knew that as long as Centre Point stayed unoccupied it remained a highly disposable and valuable asset.

The vast empty tower soon gained the nickname “London’s Empty Skyscraper” and the first organised protests took place in 1969. Calling the building an affront to the homeless the protestors unfurled a banner declaring “Cathy Come to Centre Point”.

The following year the Kinks sang about Denmark Street that was “shakin’ from the tapping of toes and where you could hear music play anytime on any day, every rhythm, every way”. Denmark Street, – a road in St Giles a stone’s throw from Centre Point – had been a musical road since early in the 20th century when music publishers found it a location conveniently next to London’s West End theatres. Both the UK’s famous music magazines, Melody Maker at number 19 and the New Music Express at number 5, began publishing there. At number 20 Elton John, in 1965 just eighteen and still plain old Reg Dwight, worked as an office boy for one of the large music publishers Mills Music. Paid just £5 per week he could not possibly have dreamt that within eight years he would be responsible for an incredible 2% of the World’s entire record sales.

In 1965 the American folk-singer Paul Simon walked into the same Mills Music with two songs he had recently written, The Sound of Silence and Homeward Bound. Unfortunately homeward bound was exactly where the man responsible for listening to new music sent him after rejecting the songs for being uncommercial and too complicated. After being turned down Simon decided to start his own publishing company called Charing Cross Music and has subsequently, and sensibly, kept the rights to all his music ever since.

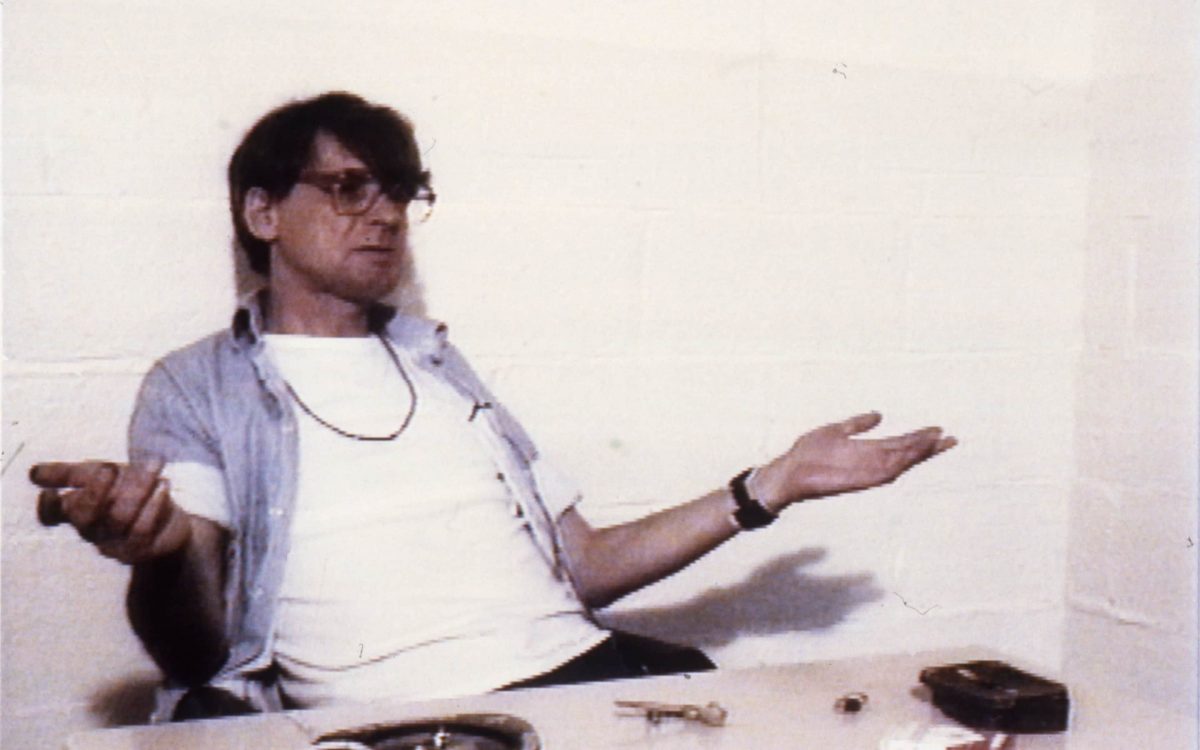

Paul Simon singing at the Jacquard Club in Norwich in the 1960s.

EDP staff photograph. Ref: M1298-33A

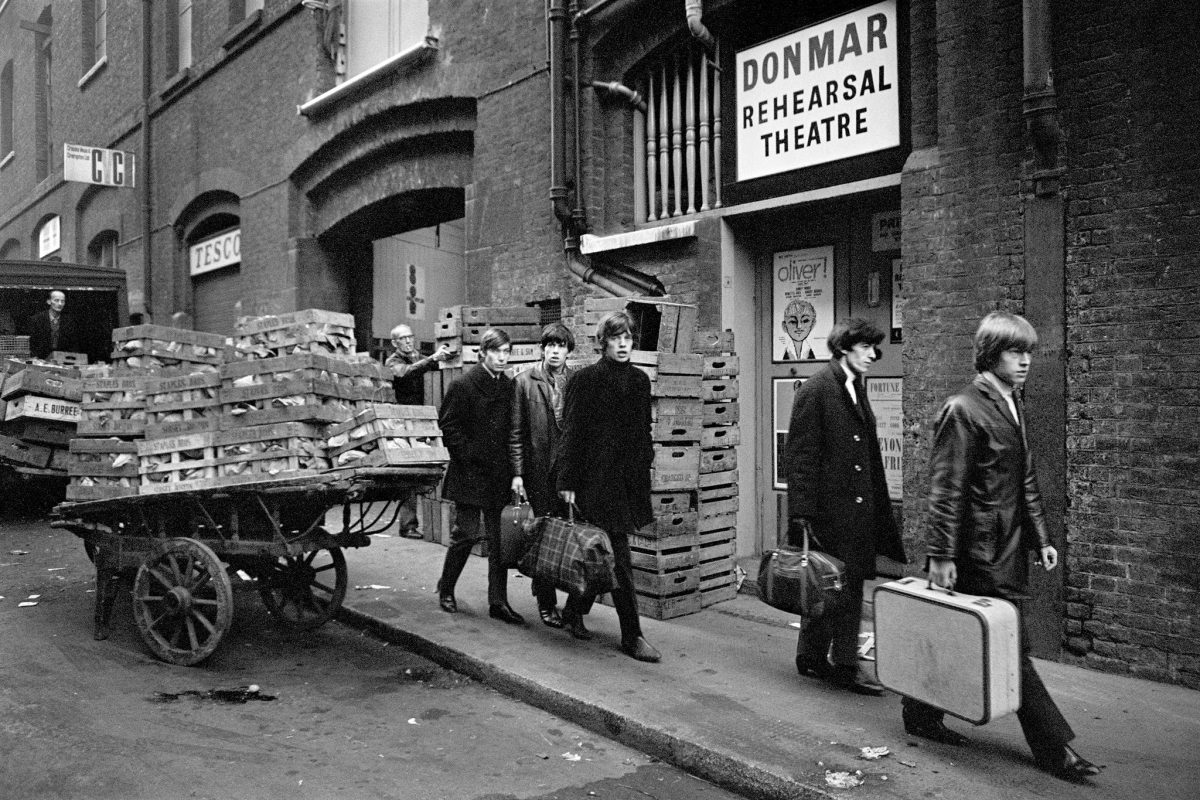

A couple of years before, in November 1963, The Rolling Stones made some demo recordings at Regent Sounds studio in Denmark Street – mostly new songs they had recently been practising and playing during their nationwide tour. The band loved the sound of the primitive, cramped studio that used actual egg-cartons as soundproofing and in January 1964 they recorded, on the two-track revox recorder, their first LP called, simply, The Rolling Stones.

In February they started recording Buddy Holly’s Not Fade Away but in the middle of a gruelling tour the group were tired and fractious and had almost given up working out how to record it. Andrew Oldham, their manager and producer, phoned his friend Gene Pitney – the American music star who was currently in London, for inspiration.

Pitney soon turned up but also brought along the producer Phil Spector at that time at the height of his fame and who in the preceding year had just produced Da Doo Ron Ron and Then He Kissed Me by The Crystals and Be My Baby and Baby, I Love You by The Ronettes. The Americans were armed with several bottles of inspiring brandy and the mood, not surprisingly, turned much for the better and Not Fade Away was at last recorded. Phil Spector is listed as playing the maracas on the recording, although in reality his instrument was an empty cognac bottle hit with a half-crown coin.

At number 9 in Denmark Street, was the Giaconda Cafe – a mod hang-out and where David Bowie met his first backing band – the Lower Third. It was also where he met Vince Taylor – known mostly these days for his song Brand New Cadillac, later covered by The Clash on London Calling but also the man that inspired Ziggy Stardust. David Bowie in an interview with Alan Yentob once spoke of Taylor:

I met (Vince Taylor) a few times in the mid-Sixties and I went to a few parties with him. He was out of his gourd. Totally flipped. The guy was not playing with a full deck at all. He used to carry maps of Europe around with him, and I remember him opening a map outside Charing Cross tube station, putting it on the pavement and kneeling down with a magnifying glass. He pointed out all the sites where UFOs were going to land. He was the inspiration for Ziggy ….

After spending too much of his life in prisons and psychiatric institutions while pretty much continually ‘out of his gourd’, Vince Taylor died in 1991 in Switzerland at the age of 52.

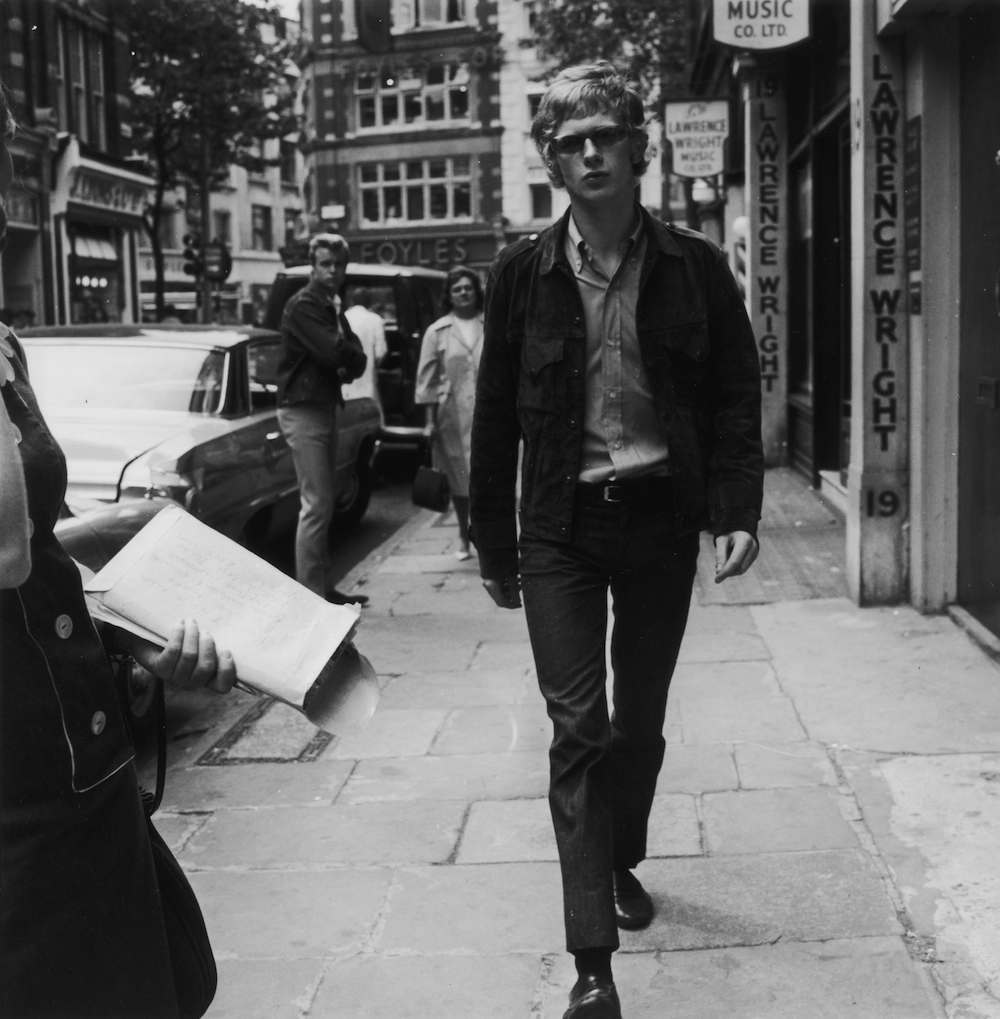

10th August 1964: British music executive Andrew Loog Oldham, manager and promoter of The Rolling Stones in Denmark Street, London, popularly known as Tin Pan Alley. (Photo by Richard Chowen/Evening Standard/Getty Images)

Denmark Street, London 1972 – courtesy of Glen Fairweather

By the mid-1970s the Giaconda snack bar had become a punk hang-out with groups such as The Clash and The Slits wasting their hours drinking tea. A few doors down from the cafe the Sex Pistols rehearsed and lived in a grotty flat above a shop at number 6 (they eventually left after struggling to find the measly £4 weekly rent).

Denis Nilsen, the infamous serial killer who murdered at least fifteen men in his North London flat in the late 1970s and early 80s, worked at the Job Centre at 1 Denmark Street for several years. In 1980, which would have been right in the middle of his killing spree, he offered to help with the food for the office Christmas party and brought along a large saucepan. Former colleagues only realised during the trial that this was the same saucepan that had been used to boil the heads of several of his victims.

In 1973 it became known that Centre Point’s estimated value was now worth £20 million. This meant it had become the most profitable London property ever and made it even more controversial. A few months later, in January 1974, protesters managed to actually get inside the building after two of them had managed to get jobs as security guards. One of the squatters described the building as “the concrete symbol of everything that is rotten about our society”. The protest, which actually only lasted a couple of days, went on to inspire the name Centrepoint for a new homeless charity that still exists today.

30th December 1973: Protesting squatters occupy the Centrepoint building in central London and advocate its use as a residential block instead of an office. (Photo by Stroud/Express/Getty Images)

By the 1990s many Londoners started to appreciate the aesthetic qualities of Centre Point and in 1995 it was made a Grade II listed building with the Royal Fine Art Commission praising Colonel Seifert’s building as having an ‘elegance worthy of a Wren steeple’.

With the construction of London’s 12th tube line – the Elizabeth Line due to open at the end of 2019 – the area around Centre Point has been completely redeveloped. The building itself is again courting controversy and for exactly the same reason as it did fifty years ago. At a time of housing problems and homelessness the developer that has turned Centre Point into luxury apartments has reportedly given up trying to sell the flats. After receiving too many “detached from reality” low offers they have decided to leave the building partially unoccupied. Fifty years after Centre Point was initially completed it can again return to its old nickname, this time slightly amended, – “London’s Half Empty Skyscraper”.

If you’d like to hang out where David Bowie, Vince Taylor, the Clash and the Slits spent hours of their time, the Giaconda Café at 9 Denmark Street is now the Flat Iron steak restaurant.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.