On Easter Sunday morning in 1992, just two hours after he had been speaking to a television producer about yet another comeback, and five days after being released from hospital after a heart-scare, seventy-five- year-old Frankie Howerd collapsed and died. Benny Hill, seven years younger than Howerd, was quoted in the press as being ‘very upset’ and saying, ‘We were great, great friends.’ Indeed they had been friends, but Hill hadn’t given a quote about his fellow comedian, he hadn’t even been asked for one – he couldn’t have been – because he was already dead. The quote about Howerd had actually come from Hill’s friend, former producer and unofficial press agent Dennis Kirkland, who hadn’t been able to get in contact with Hill and was starting to worry.

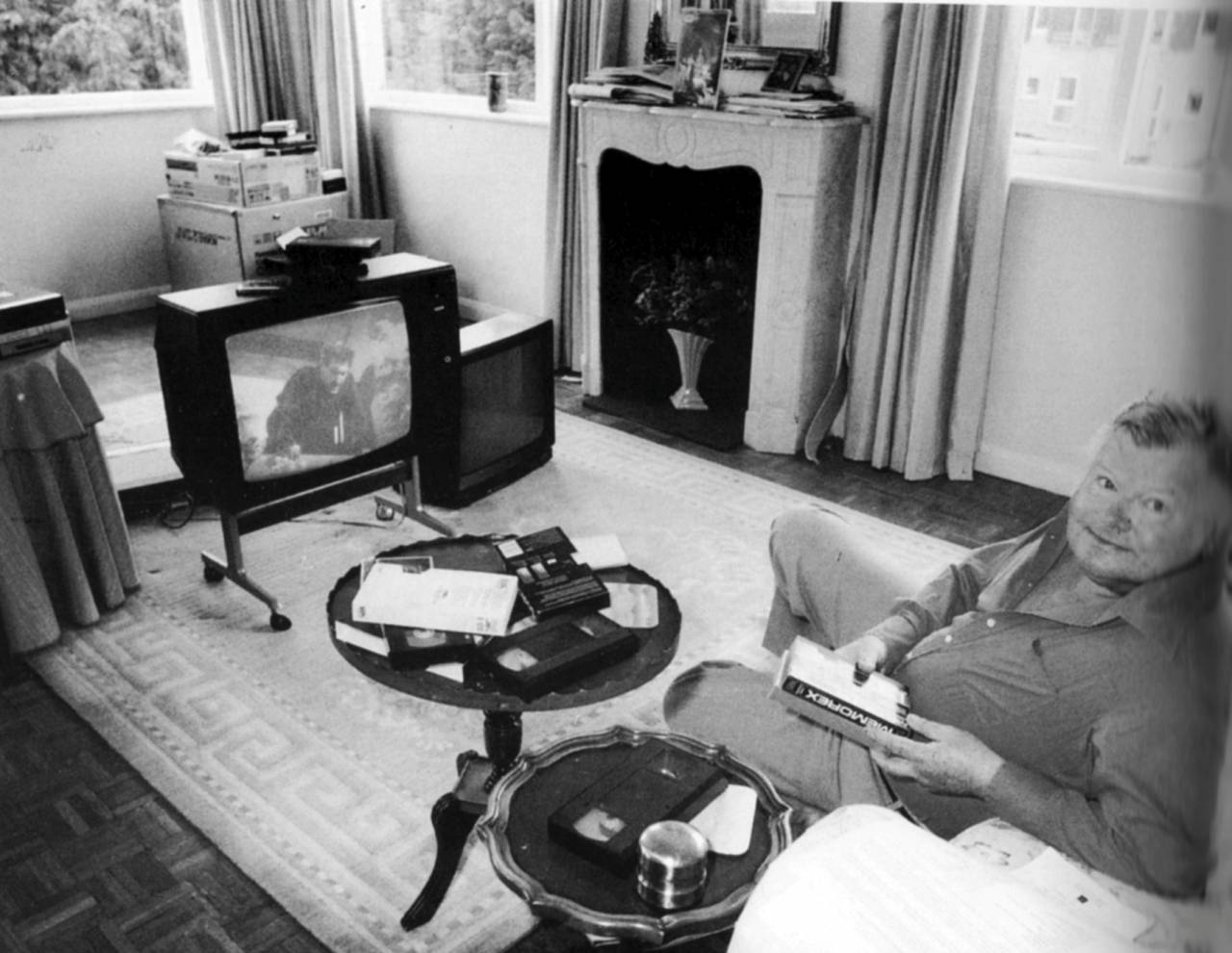

It wasn’t until the 20th, the day after Howerd had died, that a neighbour noticed an unpleasant smell coming from Flat 7 of Fairwater House on the Twickenham Road in Teddington. The neighbour contacted Kirkland, who was a regular visitor to the Teddington apartment block, and it wasn’t long before the television producer was climbing a ladder and peering through the window of Hill’s second-floor flat. Inside he saw his friend surrounded by dirty plates, glasses, videotapes and piles of papers, slumped on the sofa in front of the TV. The body was blue, bloated and distended and there was a dried trickle of blood that had seeped from one of his ears. Hill had been dead for two days. He had only been seen in public a few days before when he had sat in the audience of Me & My Girl at London’s Adelphi Theatre. Benny had gone along to see Louise English, an ex-Hill’s Angel who was appearing with Les Dennis. On the same evening, having recovered from heart trouble himself just a few months earlier, Benny had sent Frankie a telegram: ‘Stop stealing my act – I do the heart attack jokes.’

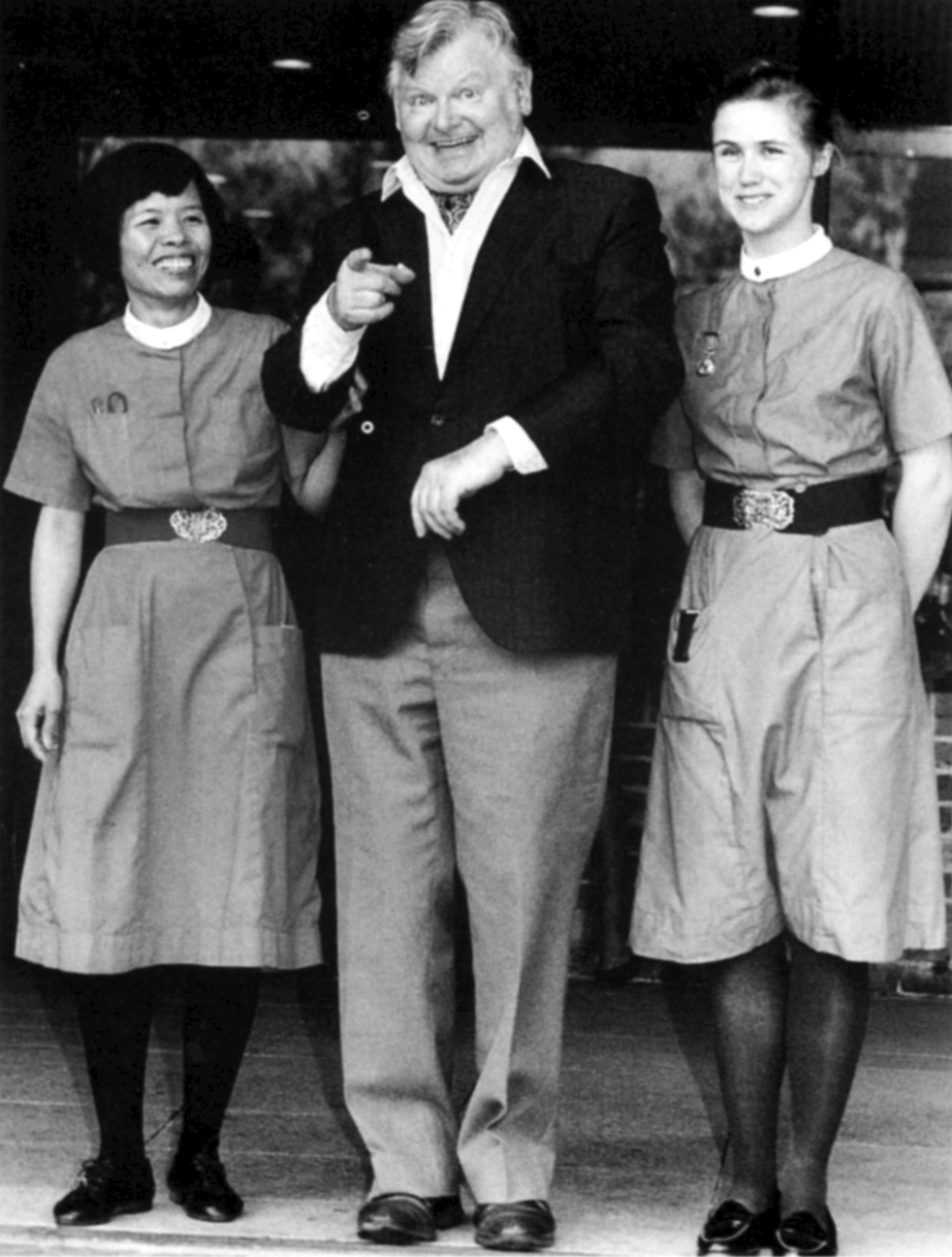

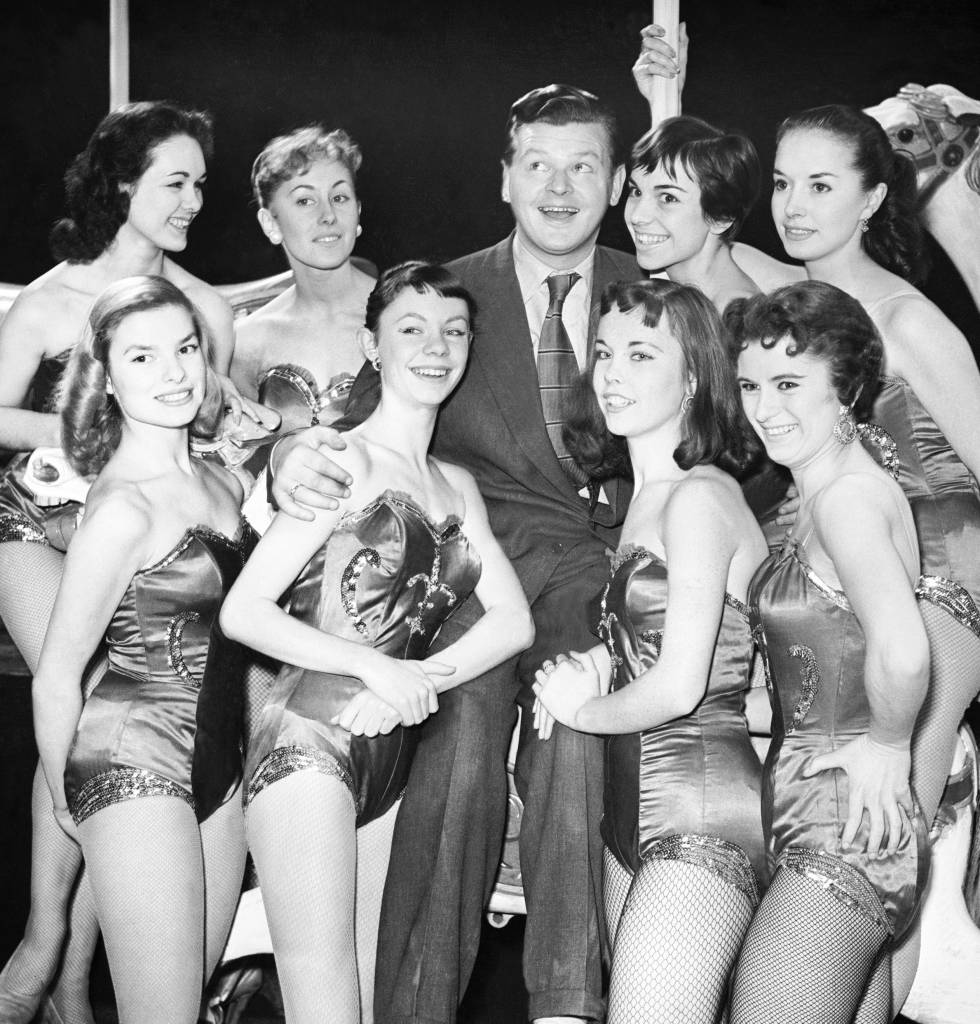

Frankie Howerd, who died the day after his friend Benny Hill, with Norman Wisdom (far left) in ‘Fine Goings On’, BBC series in 1951.

Benny Hill’s flat was on the second floor of Fairwater House in Twickenham. Photo by Rob Baker

During the summer of 1940 and during the height of the Blitz, Alfred Hawthorne Hill or, as he was usually known, Alfie arrived at Waterloo on a Southampton train. He was just seventeen. He’d given up his Eastleigh milk round, which really did have a horse and a cart, and he had sold his drum kit for £6 to finance the next part of his life. There was almost nothing in this Max Miller fan’s head but an ambition to succeed as a comic performer – show business was in the family’s blood; both his father and his grandfather had once been circus clowns. He had with him the addresses of three variety theatres in his pocket, but after a week of sleeping rough in a Streatham bomb shelter, it was luck rather than judgement that enabled the naive Hampshire boy to get a dogsbody job from a kindly agent. Hill remembered this time in 1955: ‘At the Chiswick Empire they did not want to know about Alf Hill. I had much the same reception at the “Met”, but at the Chelsea Palace I was lucky enough to arrange to see Harry Benet at his of office the next morning.’ Hill turned up at Benet’s Beak Street office and was offered £3 per week to be an assistant stage manager (with small parts) for a new revue called Follow the Fan. For years after Hill would often joke that although he was no longer an ASM, he still had small parts.

Twelve months or so later Hill, now eighteen, had become eligible for conscription but by now he was having the time of his life. He thought naively that by travelling around the country (he was now with Send Them Victorious, another revue) he could pretend he had never received the OHMS manila envelope ordering him to enlist. The ruse worked until November 1942, when the show was at the New Theatre in Cardiff for the last engagement before the pantomime season. Two military policemen presented themselves at the theatre stage door and Alfie Hill was ‘advised’ to give himself up. He couldn’t drive and he knew nothing about engines, but within a month Hill found himself a private in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers as a driver and mechanic. Not surprisingly, considering his lack of knowledge or interest in engines, Alfie Hill played no real useful part in the war. Although he was taught to drive in the army he would subsequently never own a car or drive in his civilian life.

Not long after VE Day, and when he was in London on leave, Hill applied to be part of the services’ touring revue called Stars in Battledress. There was one problem: he didn’t have ‘an act’, and he had just twenty-four hours to create one. For inspiration he walked to the Windmill Theatre on Great Windmill Street in Soho – he knew that it was the one place in London where you could see comedians during the day. He noticed one Windmill turn in particular, a man called Peter Waring whose scripts were written by Frank Muir, who at that time was still attached to the RAF. Hill would later say: ‘Waring was the biggest influence on my life. He was delicate, highly strung and sensitive…when I saw him I thought, “My God, it’s so easy. You don’t have to come on shouting, ‘Ere, ’ere, missus! Got the music ’Arry? Now missus, don’t get your knickers in a twist!’ You can come on like Waring and say, ‘Not many in tonight. There’s enough room at the back to play rugby. My God, they are playing rugby…’

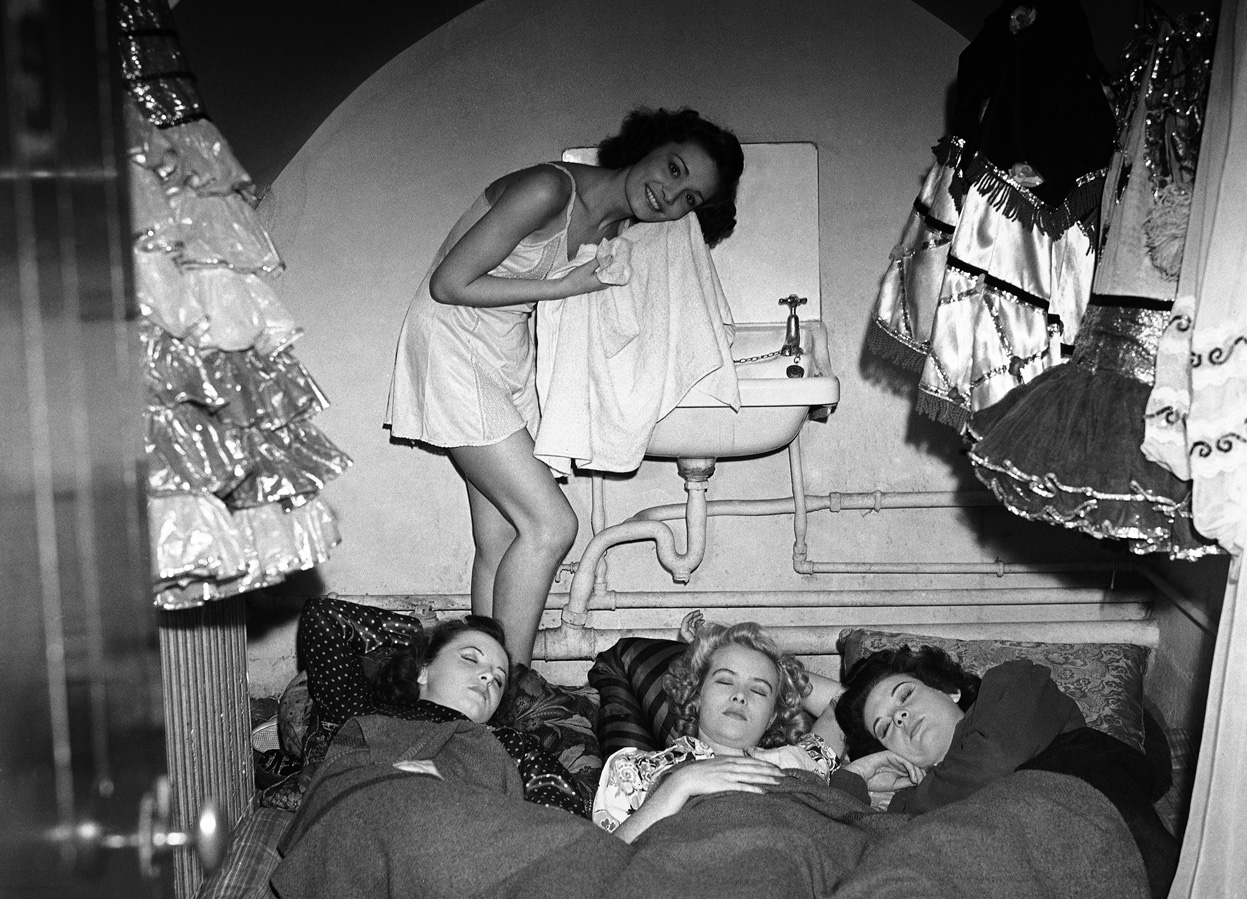

The Windmill Theatre

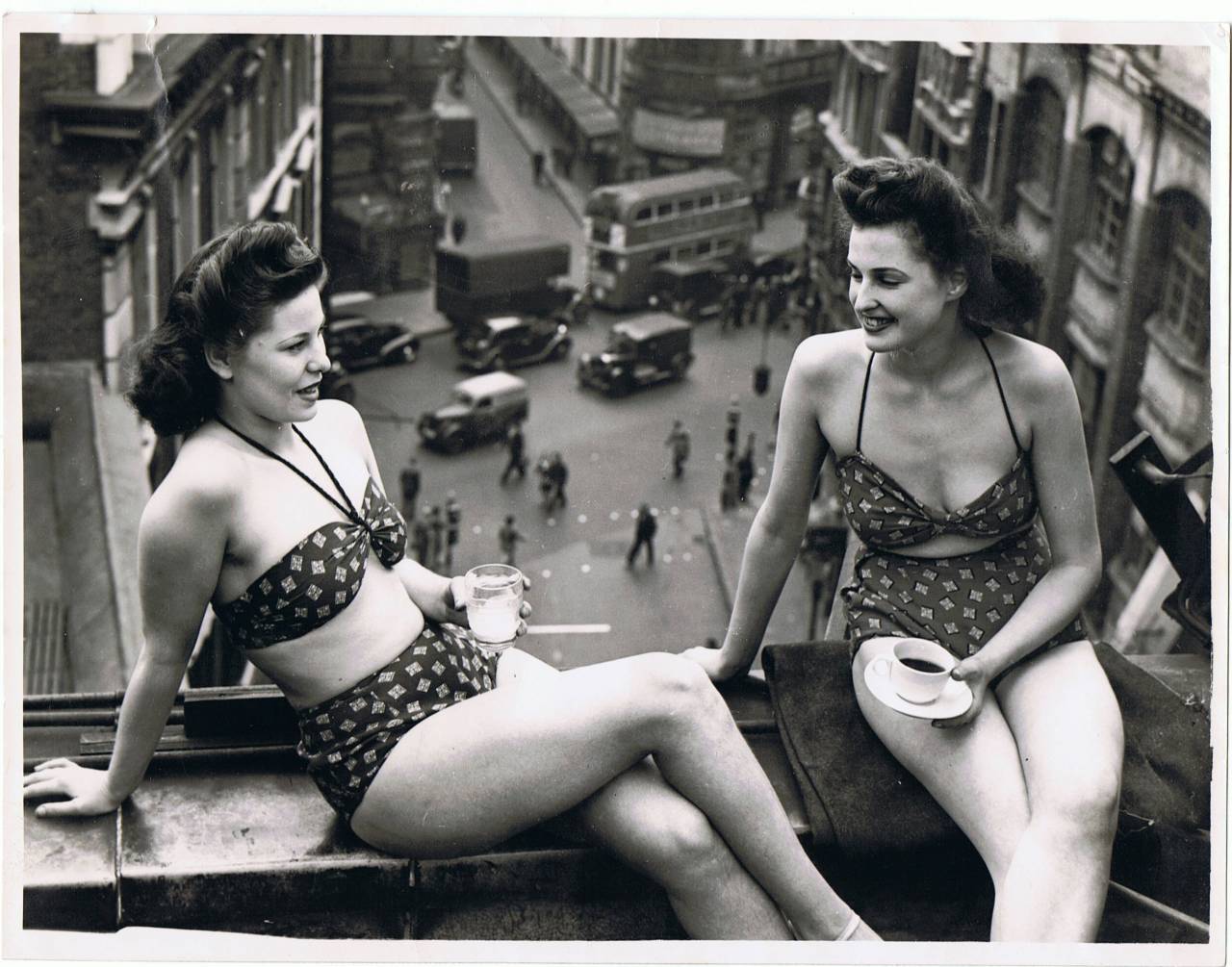

The Windmill Theatre on the corner of Great Windmill Street and Archer Street, just off Shaftesbury Avenue, was a magnet to many of the new wave ex-servicemen comedians, of whom there were many. The theatre was infamous for its risqué dancing girls and nude tableaux, but the shows also featured a small resident ballet company, a singer or two and some brand-new comedians usually at the start of their career. It was a tough crowd for the comedians – not too many patrons were there for the jokes.

The theatre had been bought in 1930 by a seventy-year-old ‘white- haired, bright-eyed little woman in mink’ called Mrs Laura Henderson whose late husband ‘had been something in Jute’. At the time it was a run-down old cinema called the Palais de Luxe (actually one of the first in London) but she had the building extensively rebuilt, glamorously faced with glazed white terracotta and renamed the Windmill Theatre. Under the careful guidance of her manager Vivian Van Damme, a small neat man who more often than not would be smoking a cigar, the theatre slowly became a success. The ‘Mill’, as it became known in its heyday, started to present a non-stop type of revue that had a terrible title which assimilated the word ‘nude’ and ‘revue’ and was called Revudeville.

Van Damme, amusingly known as VD to everyone backstage, had an astute judgement of both English sexual taste and of what the Lord Chamberlain – the national theatre censor – would allow. ‘It’s all right to be nude, but if it moves, it’s rude,’ said Rowland Thomas Baring, 2nd Earl of Cromer, who was the Lord Chamberlain at the time. On the Sunday night before any new show opened Van Damme would invite the Earl of Cromer to a special performance. To make the censor’s mood amenable to what he was about to see, VD made sure there was generous hospitality before the curtain was raised. It was said that the Lord Chamberlain never delegated his responsibilities on these occasions.

At the beginning of the war the government ordered compulsory closure of all the theatres in the West End – a stricture that, due to many protests, ended less than two weeks later. The Windmill re-opened immediately and stayed open throughout the rest of the war with five or six performances a day. The shows started at 11 a.m. and continued until 10.35 p.m. at night. During the worst of the Blitz it was sometimes too dangerous to expect people to get home safely and the stagehands and performers often slept in the lower two floors underground. Around 1943 the theatre created its famous motto – ‘We never closed’ – although wags quickly changed this to ‘We never clothed’. In fact the ‘Mill’ became a semi-cherished institution and garnered a reputation of defiance. This, together with Van Damme’s tasteful ‘girl-next-door’ version of English femininity, made the Windmill Theatre a major symbol for London’s ‘Blitz Spirit’ all around the world. This was summed up at the theatre one evening when one naked young woman broke the ‘no moving’ rule by brazenly raising her hand to give a V-sign at a V1 bomb that had exploded nearby. She earned herself a standing ovation.

Once the audience arrived in the morning some of them would stay and watch all the six shows throughout the evening and night. Des O’Connor, just one of the comedians who got an early break at the Windmill, was on his fifth show of the day when he completely dried up. Somebody, who had been at all the previous shows that day, shouted out: ‘You do the one about the parrot next!’ During the later performances the audience that were sitting in the back of the stalls would wait for those in the front rows to get up and leave. When they did, the men at the back would quickly leap over the seats to get to the front – a daily event that became known as the ‘Windmill Steeplechase’.

Benny Hill, who by now had changed his name – he thought Alfie Hill made him sound like a cheap barrow boy and Jack Benny was one of his favourite comedians – had two auditions at the Windmill. On both occasions, and after barely finishing his first gag, he got a dreaded ‘Thank you, next please’ from Van Damm somewhere in the darkness of the stalls. He certainly wasn’t the only comedian who would later go on to become a huge star but was rejected by the Windmill Theatre. Both Bob Monkhouse and Norman Wisdom also failed to get past the one- man Van Damm judging panel. The list of comics who did perform at the Windmill is extraordinary, however, and included Jimmy Edwards, Tony Hancock, Arthur English, Harry Secombe, Peter Sellers, Michael Bentine, Bruce Forsyth, Dave Allen, Alfred Marks, Max Bygraves, Tommy Cooper and Barry Cryer. There was a comedy revolution taking place and performers who, in a sense, had wasted years of their young adulthood on the war, were desperate to make up for lost time. They had seen the best of humanity and, of course, the worst. They had a connection with each other like no generation since.

For Hill, after failing his second audition at the Windmill, it was back to the working men’s clubs in parts of London like Streatham, Tottenham and Harlesden. In those days the Soho agents never actually mentioned money and used to show the amount that was to be paid by laying fingers on the lapels of their jackets. One finger meant £1 while two fingers meant double. It was nearly always the former for Benny back then. As the months went by his act was getting more and more polished and in 1948, in a rehearsal room across the road from the Windmill, he had an audition as Reg Varney’s straight-man in a revue called Gaytime. There were only two people auditioning for the part and Hill had performed an English calypso (this would have been pretty rare just after the war), which he sang to his own guitar accompaniment:

We have two Bev’ns in our Cabinet/Aneurin’s the one with the gift of the gab in it/The other Bev’n’s the taciturnist/He knows the importance of being Ernest!

After he had performed his musical comedy turn, Hill was told by Hedley Claxton, an impresario who specialised in seaside shows, that he had got the job. The other contender for the role that afternoon in 1948 was a young impressionist from Camden called Peter Sellers. Later that year Peter Sellers secured a six-month booking at the Windmill performing in sketches or sometimes as an impersonator. It wasn’t his first appearance at the Windmill. As a child he had performed in a show with his mother Peg, who was a burlesque dancer at the theatre not long after it opened. Hill and Reg Varney’s double act was generally a success, and they were signed up for three seasons of Gaytime and subsequently a touring version of a London Palladium revue called Sky High. The weakest spots in the shows were Hill’s solo performances – he found it difficult to engage with the audiences, especially in the north of England. When the revue opened at the Sunderland Empire the local newspaper wrote: ‘I thought Reg Varney’s personality pleasing and warming, but was not so “taken” with some of his comedy.’ Presumably out of kindness there was no mention of his comic partner. Hill had completely died in his own solo spot and it had ended after the audience started giving him a slow handclap.

By this time Hill had already appeared on BBC radio a few times but struggled to make his mark. A particularly damning BBC report on Benny Hill, dated 10 October 1947, said:

Ronald Waldman: The only trouble with him was that he didn’t make me laugh at all – and for a comedian that’s not very good. It’s a mixture of lack of comedy personality and lack of comedy material. Harry Pepper: I find him without personality and very dully unfunny.

In 1950, at a time when only one in twenty households owned a television, Hill, unlike many performers and agents who either feared it or thought it a flash in the pan, realised that television would be huge and all-consuming. He understood that it would gobble up comic material and that it was already ending the career of variety artists who had successfully performed the same act all their lives. Comic writers started to be as important as the performers, perhaps even more so, and Hill started to write literally hundreds and hundreds of sketches, eventually submitting great numbers of them to the BBC. The head of Light Entertainment was now Ronald Waldman, who three years previously had criticised Hill’s lack of comedy material and the ability to make him laugh at all. This time, however, Waldman was more than impressed and offered Benny Hill his own show right there and then.

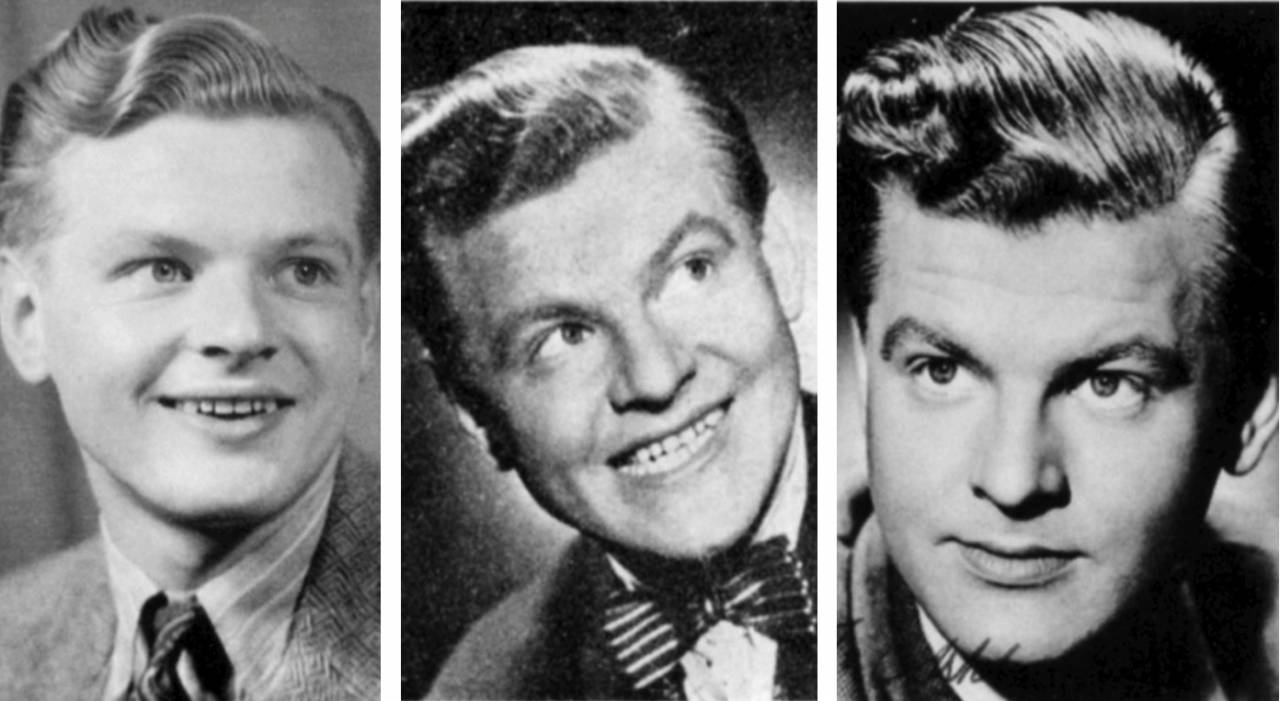

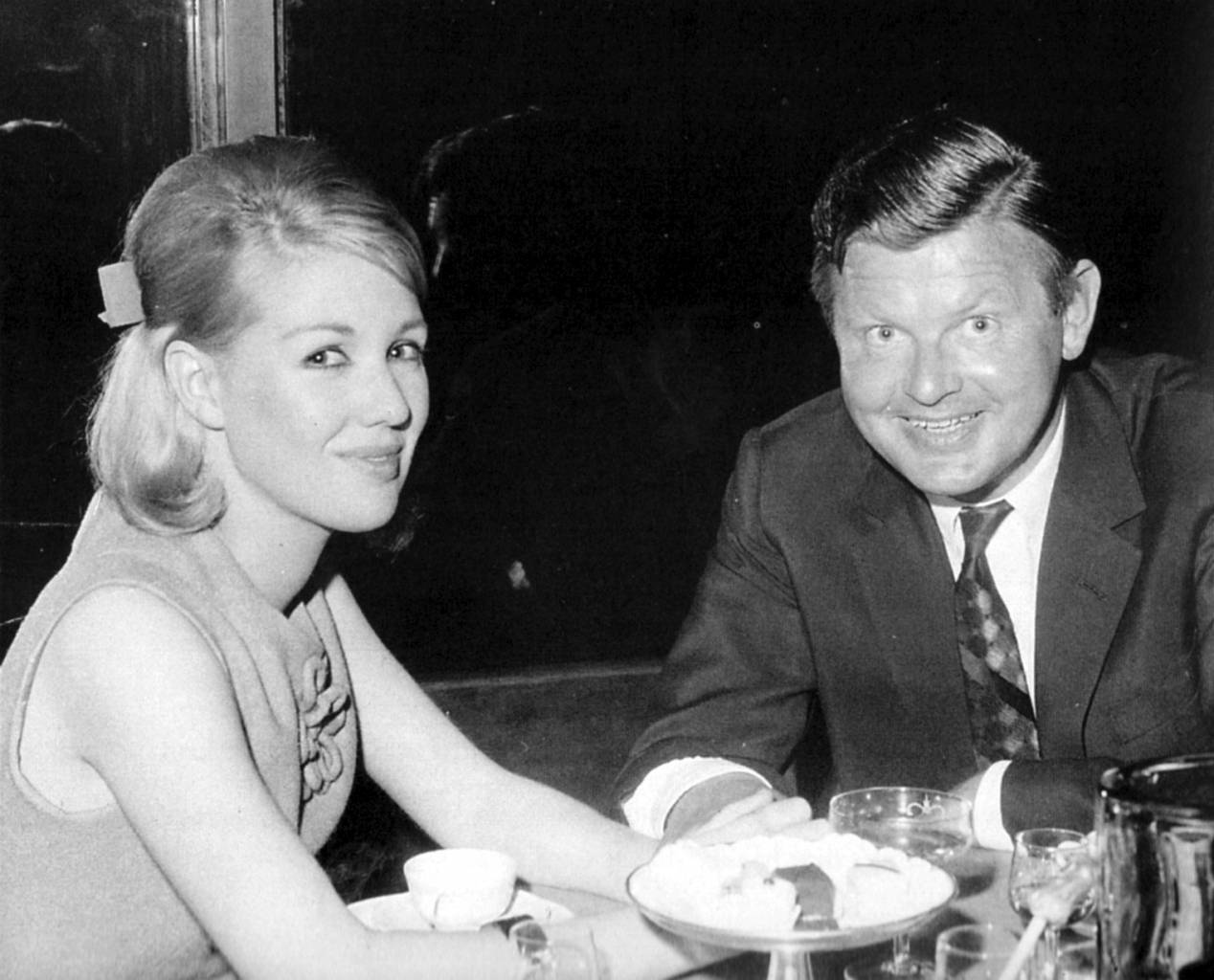

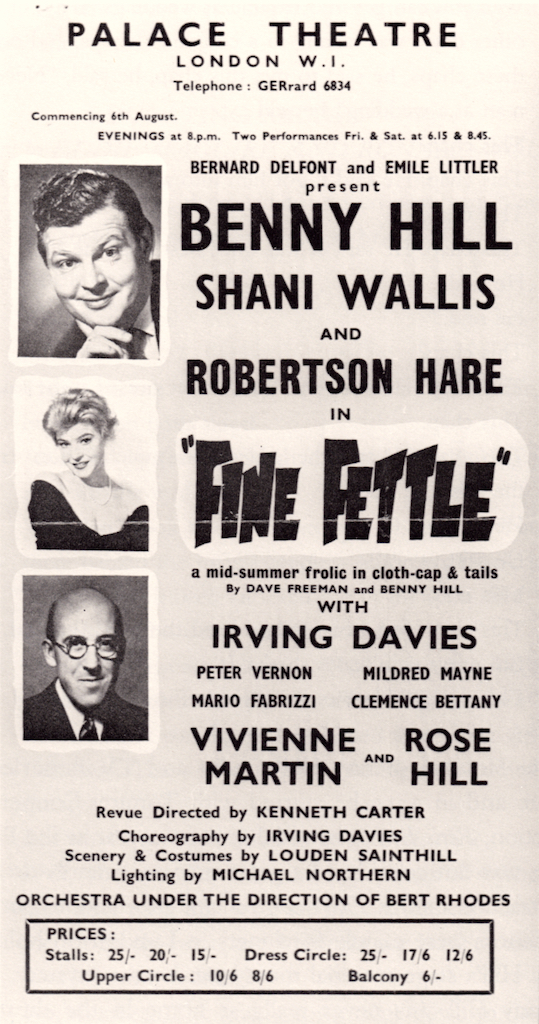

Benny Hill in ‘Fine Fettle’ at the Palace Theatre in 1956. Hill was never comfortable performing live.

Hi There was transmitted on the BBC on the evening of 20 August 1951 and the 45-minute one-off show, featuring a series of sketches wholly written by Benny Hill, was relatively well-received. It wasn’t until four years later, however, that Hill got his own BBC series when in January 1955 the first ever The Benny Hill Show was broadcast. Hill was always a relatively uncomfortable performer on stage. Roy Hudd once wrote: ‘I saw him several times live and he never seemed totally at home with an audience.’ Dennis Kirkland later wrote that ‘He made no secret of his hatred for live theatre. It made him sweat; literally shake with nerves.’ The new medium of television utterly suited Hill with his ‘conspiratorial glances and anticipatory smirks’ to camera. After a shaky first episode the rest of the series was a big success and in some ways set a new standard for British television comedy. Hill used all the expertise of the studio make-up department to great effect, and also utilised new technology enabling him to include recorded inserts in his sketches and use split screen trickery, for instance, to play all the panellists in parodies of programmes such as What’s My Line? and Juke Box Jury.

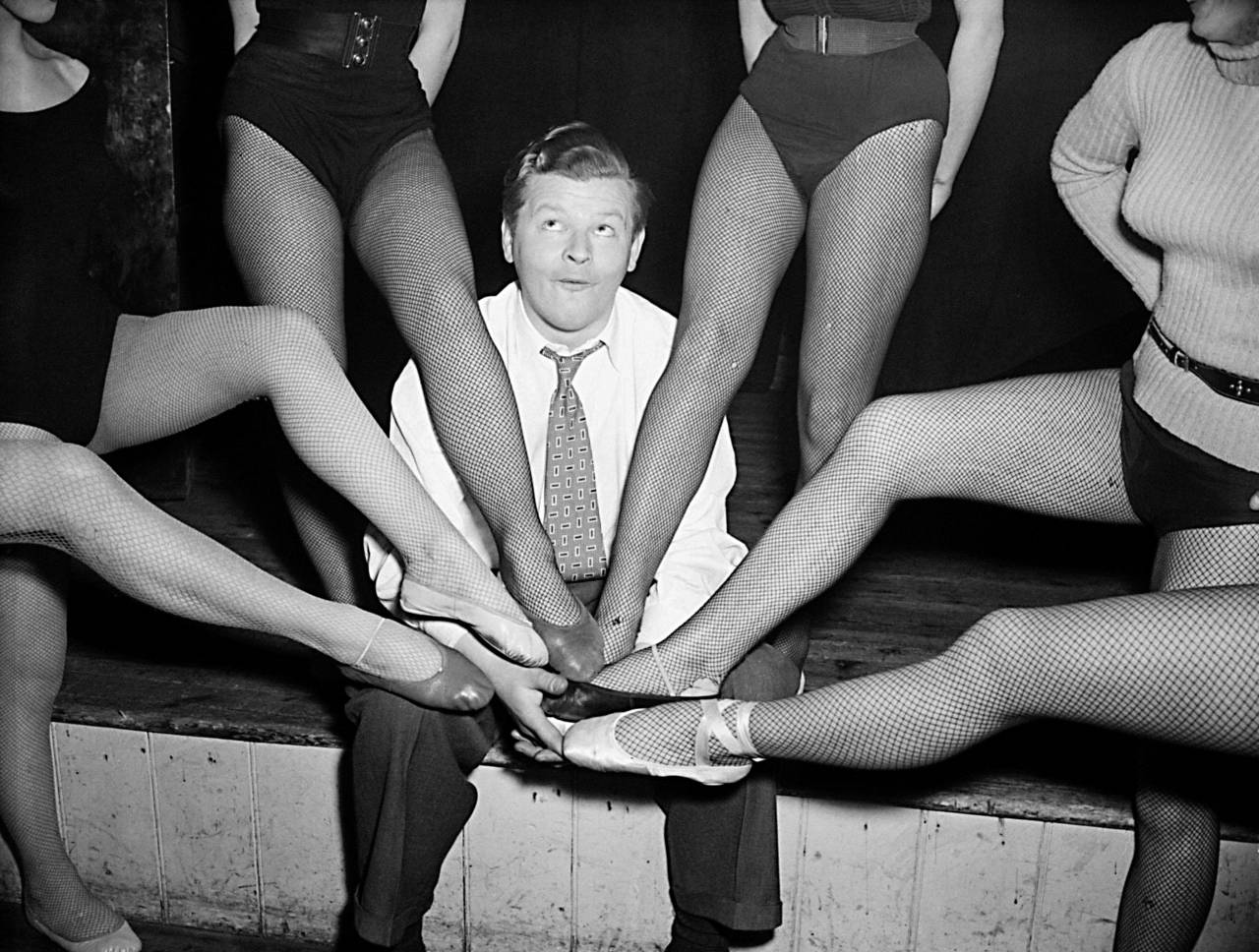

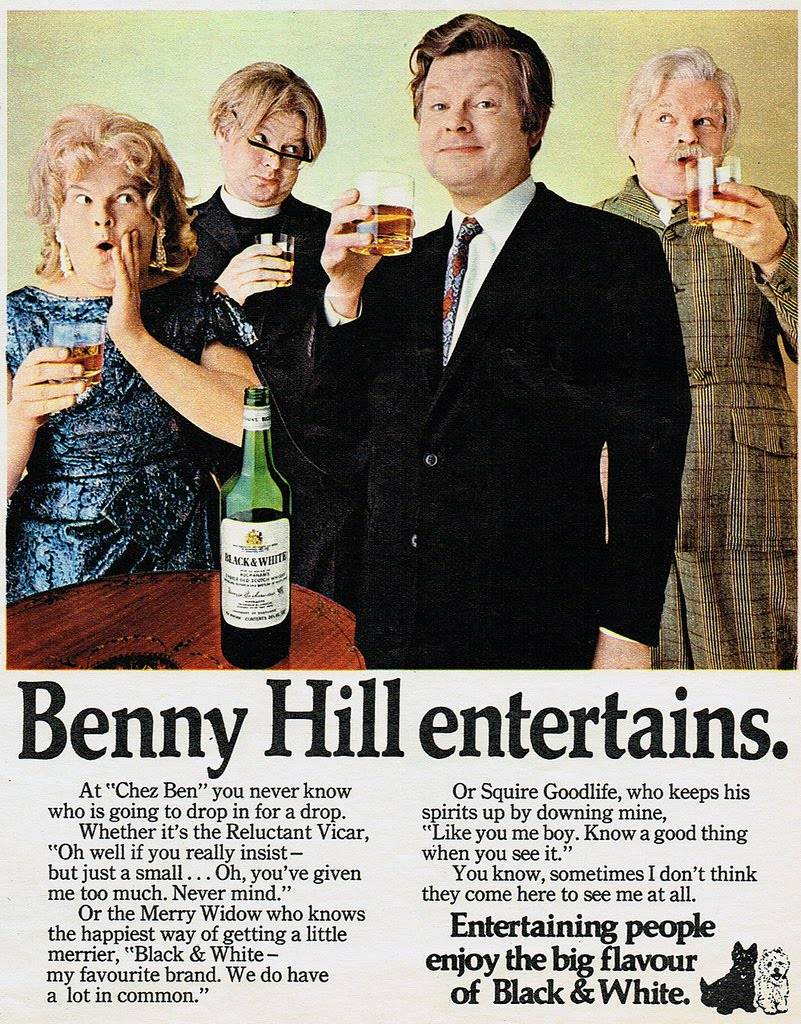

All this, to people watching at home, made old routines seem brand new. Benny Hill never looked back and was a mainstay of British television for the next thirty-five years. Initially his shows appeared on the BBC but from 1969, when the new London weekday ITV franchise needed some high-profile signings, on Thames Television. The ‘cherub sent by the devil’, as Michael Caine once described Hill, eventually became a big star all over the world. It seemed at one point, just as many in the UK were starting to find his comedy rather old-fashioned and sexist, that the rest of the world thought Benny Hill WAS British comedy. Towards the end of the eighties Colin Shaw of the Broadcasting Standards Council issued a mandate:

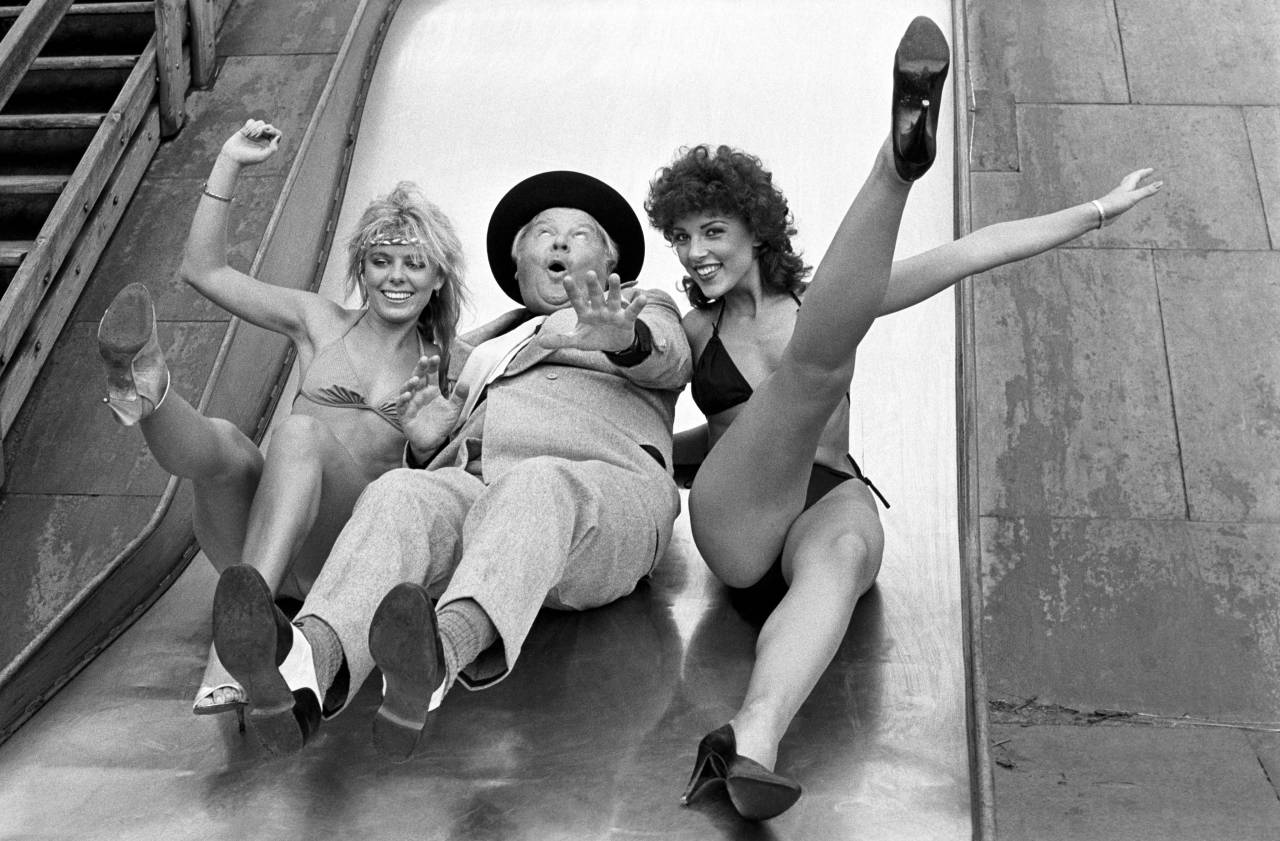

‘Although the half undressed woman has been a staple element in farce and light entertainment shows, the convention is becoming increasingly offensive to a growing number of people and should be used only sparingly … It’s not as funny as it was to have half-naked girls chased across the screen by a dirty old man. Attitudes have changed.’

Comedian Benny Hill slides down a slide with two bikini clad women during filming for his latest series (1983).

Benny Hill was very confused about the accusations of sexism in the latter part of his career. He felt that over the years his comedy hadn’t really changed and he’d been doing almost the same thing for decades. This was true; he literally had been telling the same jokes throughout his career and he was always happy to recycle his own material and others. Society around him had moved on, however, and an elderly man surrounded or chased by scantily-clad women made for uncomfortable viewing. There is no doubt that Benny Hill had an odd relationship with women and it appears that Benny Hill never really had a proper relationship during his lifetime. In 1955, just as his career was taking off at the BBC, he was interviewed by Jane Dexter in the Daily Mirror. He was surrounded by dozens of girls, ‘not all overdressed,’ said Dexter, ‘so why did he find it so dificult to find a girlfriend or wife?’ Benny explained:

It’s like working in a chocolate factory. You see so many chocolates you don’t bother to take a closer look. Besides I don’t want a glamour girl. I’d like a girl who works in an office or a factory or a shop. That’s where the pretty ones with common sense hide – and that’s where I’m looking.

In fact the closest he got to marriage was a couple of years later, with a dancer from the Windmill Theatre called Doris Deal. He took her for meals in the West End, they held hands, and it was assumed they were seeing each other. When Hill procrastinated a little too long and told her he wasn’t ready for marriage, she promptly left him. There were other close, albeit non-romantic, relationships with women through the years including a young Australian actress called Annette André (she went on to appear in Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased)). He even proposed to Annette once although, to be polite, she pretended not to notice.

It seems that Benny Hill, famous throughout the world by surrounding himself with young women, either was scared of intimate sexual intercourse or, as some un-named sources have implied, he was impotent or gay. Before the war some gay dancers he was working with asked a naive Alfie whether he was ‘queer’. Not understanding the question, he answered, ‘Not really, but I’ve got my funny little ways …’ Mark Lewisohn, in his Benny Hill biography Funny, Peculiar, recounts a conversation Bob Monkhouse once had with Benny Hill in a cafe in Shaftesbury Avenue:

‘He wanted his women to be more naive than he was, women who would look up to him. He also said it was fellatio he wanted, or masturbation. “But Bob, I get a thrill when they’re kneeling there, between my knees and they’re looking up at me. And I want them to call me Mr Hill, not Benny. ‘Is that all right for you, Mr Hill?’ That’s lovely, that is, I really like that,” I asked him why and he said, “Well, it’s respectful…”’

In 1989, twenty years after Benny Hill made his first series for Thames Television, their new Head of Light Entertainment, John Howard Davies, invited him into the offices for a chat. Howard Davies had played the title role in David Lean’s Oliver Twist as a nine-year-old in 1948, but as an adult at the BBC had worked on Steptoe and Son, Monty Python, Fawlty Towers (it was his idea to cast Prunella Scales as Sybil) and produced all four series of The Good Life. Having just returned from a triumphant Cannes Television Festival, Hill, not surprisingly, assumed that they were meeting to discuss the details of some new Benny Hill Shows. The former child-star thanked him for all the series he had made for Thames but then promptly sacked him. Howard Davies would later say, ‘It’s very dangerous to have a show on ITV that doesn’t appeal to women, because they hold the purse strings, in a sense.’

The following year, in 1990, The Benny Hill Show was broadcast in ninety-seven countries around the world, except, ironically, in Britain. Benny Hill never really recovered from the shock of the meeting with Howard Davies and he was certainly treated badly. It was only three years later that Kirkland found him dead in his apartment, just a stone’s throw from the Thames Television studios in Teddington. The worldwide success of his shows made Hill very rich and he left over £7 million pounds in his will. Unfortunately it hadn’t been updated since 1961 and all the beneficiaries, his mum, dad, brother and sister, had also all died. The money went to nieces and nephews he hardly knew.

When I was a lad and crazy to get into showbiz I used to dream of being a comic in a touring revue. They were extraordinary, wonderful shows. There were jugglers and acrobats and singers and comics, and most important of all were the girl dancers. My shows are probably the nearest thing there is on TV to those old revues. Benny Hill

Comedian Benny Hill in 1986 with his Hill’s Angels: (top, l-r) Selina Caston, Lorraine Doyle, Sue Upton, Natalie Rolls; (bottom, l-r) Zoe Bryant, Liz Jobling.

This post is an except from Rob Baker’s London history book Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics buy a signed copy here

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.