Circa 1939- A stallholder demonstrating his wares at Brixton Market

It’s not London’s oldest market – the one at Borough was first mentioned in 1276 and claims to have been in existence since 1014 – but the 150-year-old Brixton Market is certainly one of the best. Over 60 years ago Ian Nairn, the architectural critic, described it as “stalls everywhere, arcades everywhere, diving through buildings and under the railway. Meat, fish, nylons, detergent: an endless convoluted cornucopia”. Although the covered arcades Market Row and Granville Arcade (known now as Brixton Village) have increasingly converted to some excellent street-food cafes and restaurants, Nairn would still recognise the vibrant albeit rather ramshackle market today.

When the costermongers first wheeled their barrows into Brixton they wanted to take advantage of the well-to-do customers going in and out of the elegant Brixton stores which included the sophisticated Bon Marché, London’s first purpose-built department store, named (and modelled) on the original Bon Marché in Paris and the first steel-framed building in the country. Brixton at the time was a salubrious place to live and famous for its shopping, for a long time it was known as the ‘Oxford Street of the South’.

1927- An array of Christmas lights brightening department stores Bon Marche and Quin and Axtens on Brixton Road

By the end of the 19th century, some were already dismissing Brixton as populated by only the ‘servant-keeping middle-classes’. By 1931 even the middle classes were fleeing to London’s outer reaches and it told a story when the boxes at the Brixton Empress Theatre were removed to make way for more cheap seats.

When the large Empress Theatre had opened on Boxing Day in 1898 the Music Hall variety circuit was at its peak. The performers were some of the highest paid and lauded entertainers in the country. ‘I earn more than the Prime Minister,’ said the comedian Little Tich, ‘but I do so much less harm.’ By this time the large houses in Brixton were being broken up into cheap flats and lodgings, often as digs for the variety artists working at the numerous nearby theatres and music halls.

Circa 1910- The London Supperette Car Company opens a refreshment car near Brixton Station

Brixton Empress Theatre c.1920

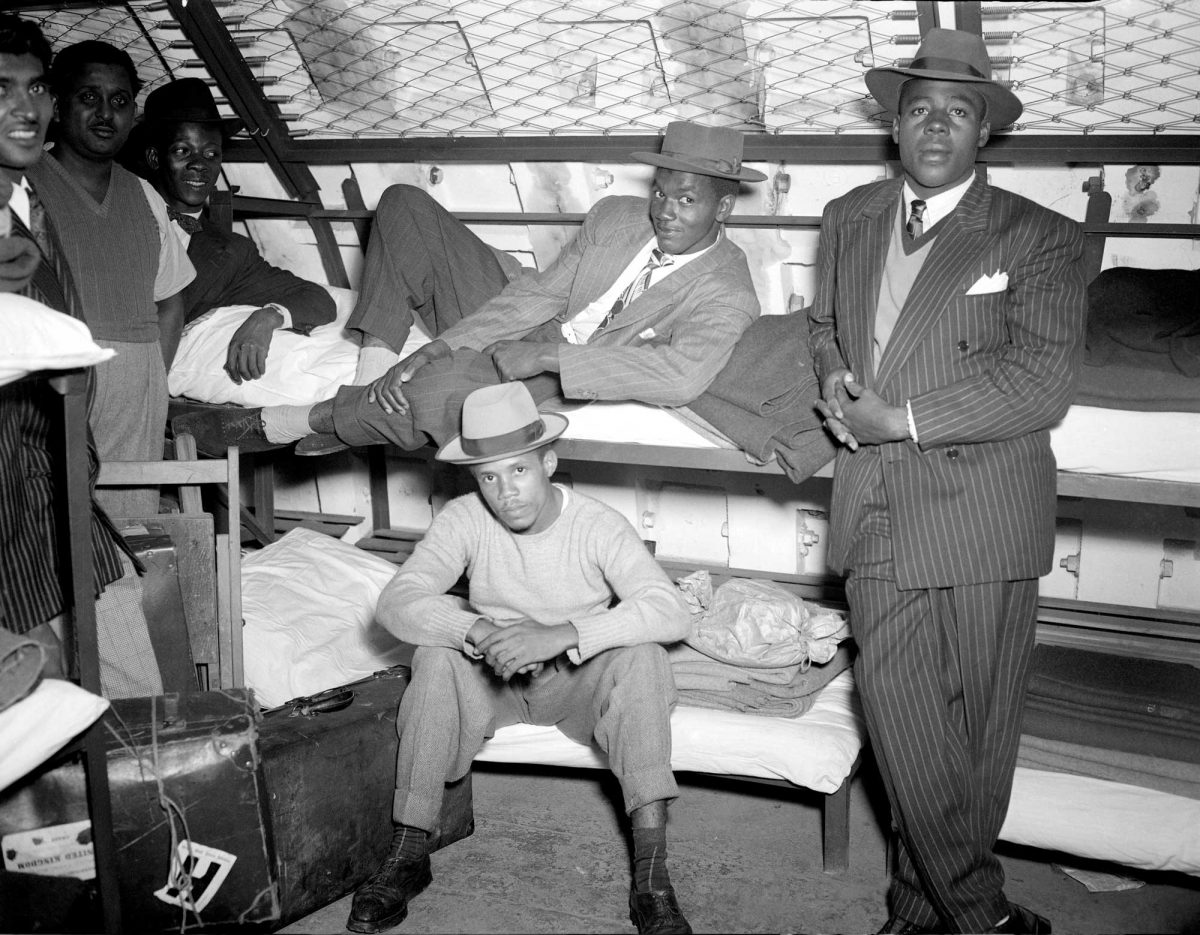

In the summer of 1948, 300 of the Empire Windrush passengers found their way to Brixton. Initially housed in the deep underground shelters on Clapham Common they soon made their way to the nearest Labour Exchange situated on Coldharbour Lane, right next to the Granville Arcade. Soon Brixton, not least because of a few friendly Jamaican landlords, became the hub of the Jamaican community in London. The market quickly adjusted and started selling yams and plantains next to the potatoes and cabbages to the appreciative new Caribbean inhabitants.

Windrush passengers in the deep level shelter at Clapham Common

In the 1950s and 1960s, however, the comedians, singers, ventriloquists and acrobats still made up much of Brixton’s population. One ex-acrobat was Tom Major-Ball who with his family, including his son John the future Prime Minister, lived around the corner from the market on Coldharbour Lane.

Abraham Thomas Ball (Major was a stage name) started appearing in Music Halls and circuses at the end of the 19th century. He was initially as an acrobat and trapeze artist but later became a successful double-act with singer and dancer Kitty Grant who would later become his wife. Known as Drum and Major they were relatively successful performing acrobatics, comic songs and comedy sketches. The year after they met they went on a tour of South America where they accidentally got caught up in a civil war in Uruguay and Major-Ball was forced to enlist in a local militia.

Unfortunately Kitty died after a tragic on-stage accident in 1928 but on her death bed she asked a young dancer called Gwen Coates, who had recently joined their act, to look after Tom. This Gwen did for the next 34 years, giving birth to John Major in March 1943.

Tom Major-Ball’s family of five, which also included a white bull terrier called Butch and a pet-budgerigar, moved to Coldharbour Lane in 1955. They lived in just two rooms – the cooker was shared on the landing with another tenant, the toilet was two floors down and there was no bathroom at all. Their landlord was called ‘Uncle Tom’ and he occupied the ground floor and basement of the house. Unknown to John Major at the time, ‘Uncle Tom’ was actually his half-brother (his father had had an affair with Mary Moss, the wife of a young musician in 1901). Tom had also been on the stage as a singer and for years appeared with his sister Jill Summers, who later achieved fame as Phyllis Pearce in Coronation Street.

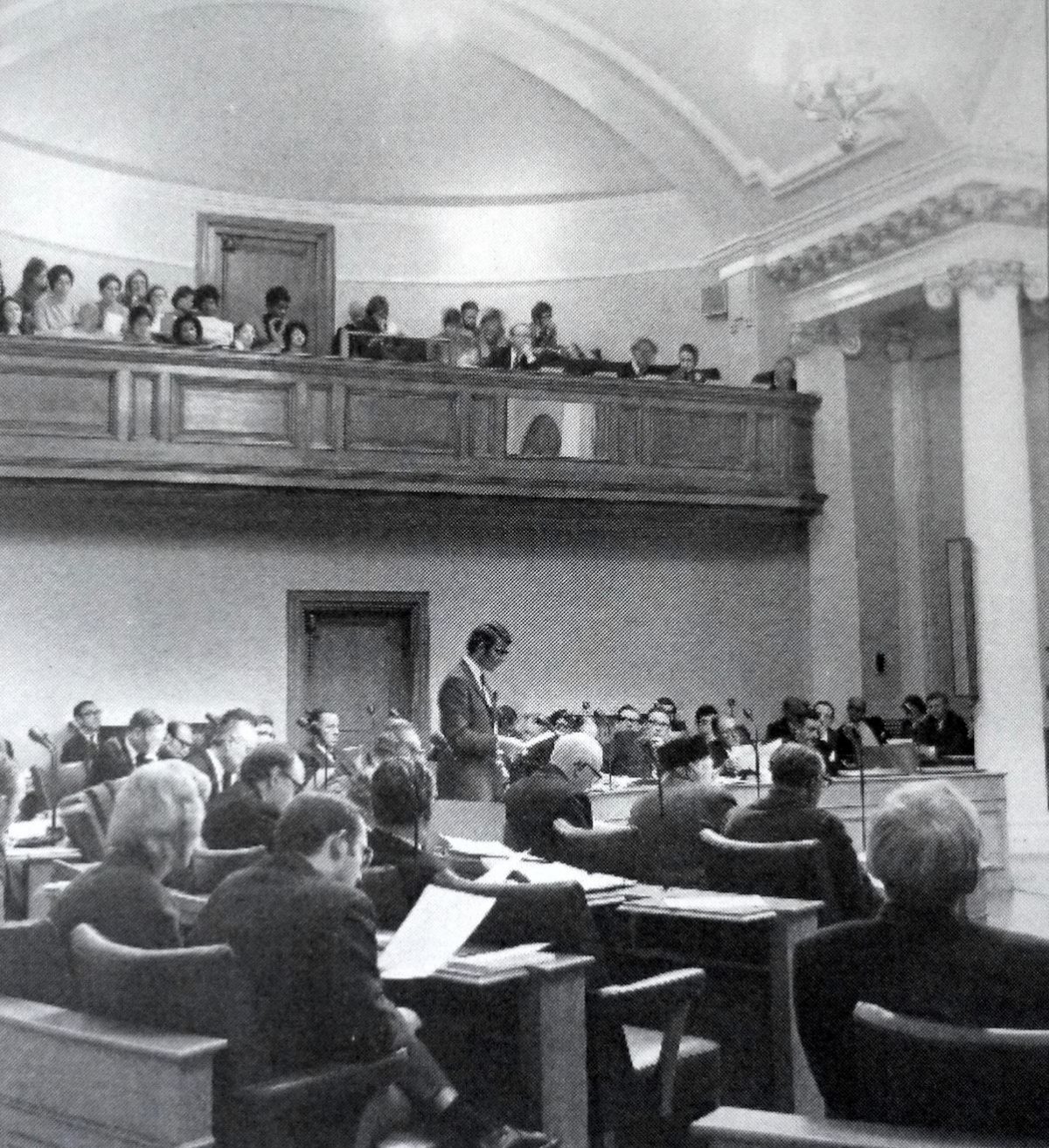

John Major addressing Lambeth Council

Another singer who worked on the British variety circuit and also a Brixton resident was Don Arden. Arden, father of Sharon Osbourne, lived on Angell Road just off Coldharbour Lane and was married to a former acrobatic dancer called Hope Shaw. Arden was relatively successful impersonating singers such as Enrico Caruso and actors such as Edward G. Robinson and George Raft. In 1955, when the Major-Balls were moving into their two-roomed Brixton flat, Arden was ‘blacked up’ as a regular on the Black and White Minstrel Show – the ‘highlight’ of his performing career.

Don Arden

Don Arden’s landlady was a pianist called Winifred Attwell who by the mid-fifties was undoubtedly one of Britain’s most popular entertainers. Trinidadian-born, her undisguised cheerful personality and well-played honky-tonk ragtime music brightened up many a ‘knees up’ in those pre-rock ‘n’ roll days. When Atwell reached number one in 1954 with ‘Let’s Have Another Party’, she became the first black musician in the UK to sell a million records. At the peak of her popularity her hands were so valuable they were insured for £40,000. The contract included a clause – and how many of us would like to sign a legal document like this – that she must never wash the dishes.

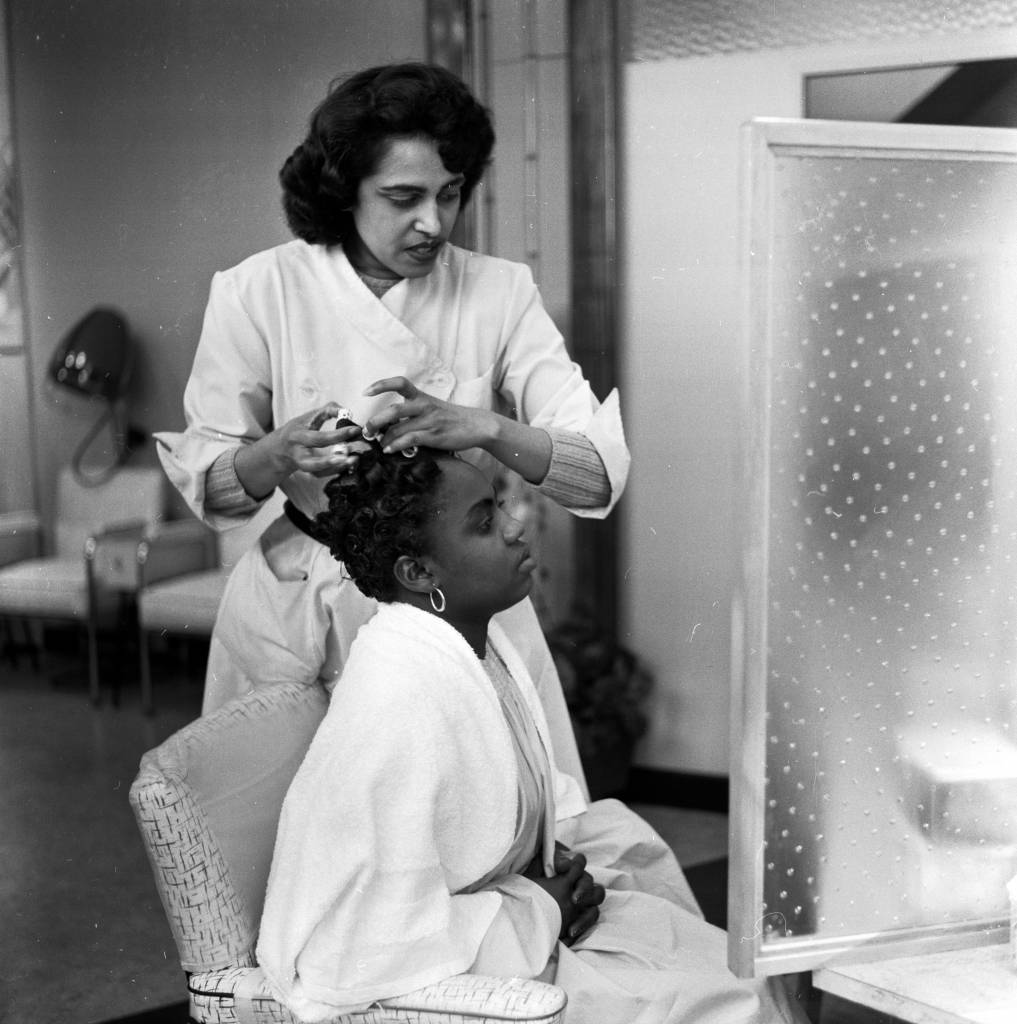

Once a resident of Brixton herself she had by now moved to leafy Hampstead but still owned properties and businesses in the area. In 1956 on the corner of Chaucer Road and Railton Road (a few hundred metres from Brixton Market) she opened what was possibly the first black women’s hairdressers in the country called The Winifred Atwell Salon.

30th April 1957- A customer has her hair straightened out at pianist Winifred Atwell’s hairdressing salon in Brixton, London. (Photo by Lee Tracey)

30th April 1957: Winifred Atwell has her hair straightened out at pianist Winifred Atwell’s hairdressing salon in Brixton, London. (Photo by Lee Tracey/BIPs/Getty Images)

Chaucer Road, Brixton – 1981

By the late Fifties tastes in music were rapidly changing. Don Arden gave up singing and became an agent and manager. He signed Gene Vincent in 1960 (by then a much bigger star in the UK than the US) and then the Nashville Teens. According to Johnny Rogan’s book ‘Starmakers & Svengalis’, when group member John Hawken complained about the amount of money they were receiving Arden told him: ‘I have the strength of 10 men in these hands’ and threatened to throw him from an office window. He then managed the Small Faces but after hearing that the impresario Robert Stigwood had discussed with the group about changing managers, Arden came to his office and also threatened to throw him out of the window. Arden would later write in his autobiography, ‘I didn’t want to hurt Stigwood. I just wanted to frighten him and get a laugh out of it’.

The far more mild natured Winifred Atwell had her last top ten hit in 1959. When record sales started to fall in Britain, she spent more and more time in Australia where she was still very popular. In 1961 her hairdressing salon in Railton Road closed down and ten years later Atwell was granted permission to stay in the country that she had begun to love.

82A Railton Road 1975

In 1981 at about the same time Winifred Atwell was granted full Australian citizenship, a Molotov cocktail was thrown through a window of The George Hotel on the corner of Effra Parade and Railton Road. It was 14 April 1981 and the second night of the infamous Brixton Riots that took place mainly as a reaction to the heavy-handed Metropolitan Police’s ‘Operation Swamp’; in just six days over 1,000 people were stopped and searched and 86 arrested. When the riots were over a small parade of shops just down from the George had also been destroyed – the building that was once the Winifred Atwell Salon had been burnt to the ground. She died just two years later from a heart attack in Sydney on 27 February 1983.

By now John Major had been a Conservative MP for about four years and had recently become a junior whip. It was also when Eddie Grant’s ‘Electric Avenue’ had entered the US charts. Originally released the previous year in the UK the song about the street that was the main part of Brixton Market had been written in response to the riots which he had watched unfurl on television: ‘People felt they were being left behind and there was a potential for violence. The song was intended as a wake-up call’. Grant was later invited back to Brixton in 2016 to open the huge illuminated Electric Avenue sign that now looks down on the street.

Electric Avenue in 1987, photo by Peter Marshall

The Empress Theatre is long gone – it was demolished in 1992 and replaced by an ‘affordable’ housing development – but Brixton Market is still a lively place and more popular than ever. Many people, worried about excessive gentrification, initially criticised Brixton Village but it gave the old market a new lease of life. The market as a whole is still a bit ramshackle and disorganised but there is, of course, a plan to structure it into something more ordered and regulated. Sixty years ago Ian Nairn feared that a grand plan that was proposed at the time would ruin the market. He hoped that it ‘was so grand that it would be deferred until planners can understand what makes the place tick’. Let’s hope Lambeth Council’s current ‘Brixton Street Market Masterplan and Action Plan’ is also deferred until they realise that most residents and visitors to the market like it just the way it is.

Armet Francis, Fashion Shoot, Brixton Market, London, 1973

Brixton Market, September 1952

Brixton High Street BHS and M&S 6th August 1963

1966- A shop supervisor hands a customer her change in a Tesco Supermarket in Brixton

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.