At the Register Office in the Chelsea Old Town Hall on the King’s Road, Judy Garland, wearing a blue chiffon mini dress, with a draped neck and ostrich feather sleeves, married a gay ex-discotheque manager and part-time jazz pianist called Mickey Devinko, better known to his friends and associates as Mickey Deans. After the brief marriage ceremony, held at mid-day on 15 March 1969, and which was actually the forty-six-year-old’s fifth, Garland said: ‘This is it. For the first time in my life, I am really happy. Finally, I am loved.’ Not that loved, it seemed, because, despite the long celebrity guest-list, none of Judy’s famous friends made it to the reception. It was held at Quaglino’s, the large and expensive restaurant opened forty years previously in 1929 and situated in Bury Street just south of Piccadilly.

Several hundred people were invited, albeit at very short notice, and only a few made it to the function. ‘I can’t understand it,’ Judy was reported to have said in the next day’s Sunday Express, ‘they all said they’d come’ Even her daughter Liza Minnelli, who had turned twenty-three just three days before, had called her mother to say, ‘I can’t make it Mamma but I promise I’ll come to your next one!’

The large formal room hired for the reception was a mistake and only accentuated the lack of guests. Glasses of champagne remained un-drunk and most of an ostentatious three-tiered cake stayed uneaten. The cake had been given to Garland six weeks previously at the end of her five-week Talk of the Town engagement. Nobody had remembered to take it out of the deep-freeze in time, however, and it was almost impossible to cut and eat.

A young actor friend of Mickey’s called Allan Warren was asked to be the wedding photographer and has described what happened:

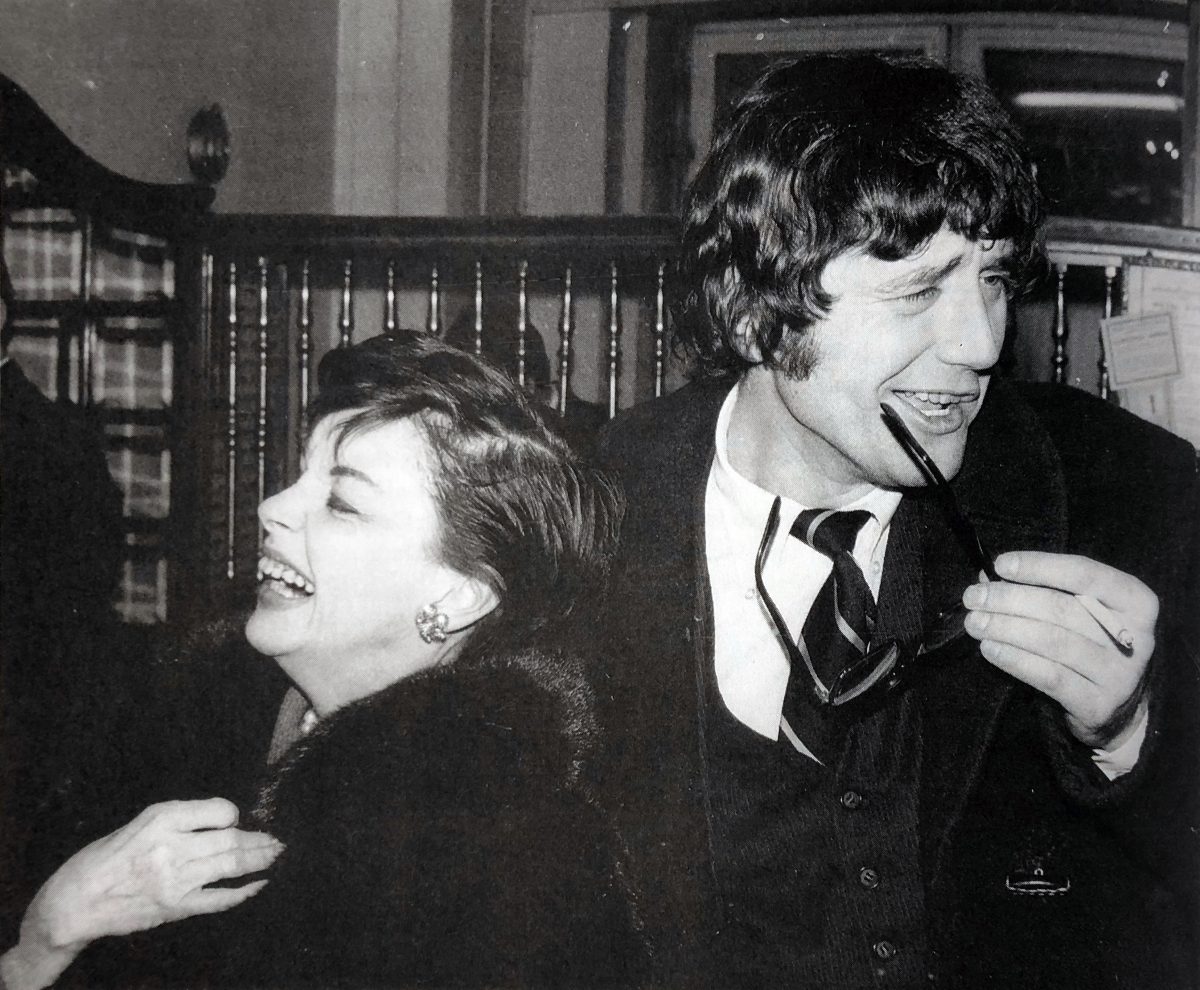

Mickey phoned and said, ‘Am not looking to stay, as I’m staying at Claridge’s, but have you got a camera? At the time I was in Alan Bennett’s Forty Years On and oddly enough had just bought one. He offered me twenty pounds for me to take some photographs of the reception. He was usually stone broke. So I laughed and said, ‘sure, who’re you marrying?’ He said, ‘Judy Garland so I can pay you’. I had never taken any pictures before, but I said I would do it. When I got to Quaglino’s, there was a small band playing, a huge amount of press and and a little group of people sitting with him in the opposite corner. One was Judy, the other Johnnie Ray and a third was a girl beside them in a wheelchair, who was never introduced. I took a few snaps including some of Judy and Mickey dancing. Then Mickey told me to dance with Judy as there was nobody else apart from Johnnie. She seemed very frail and very skinny. When we waltzed I could feel the bones of her spine sticking out. She also seemed very dazed as if on drugs, her eyes glazed over and she seemed very uptight. We danced in time to a one armed trumpet player playing Somewhere Over the Rainbow. Afterwards I left as had to get to do the play. Mickey never paid me of course!

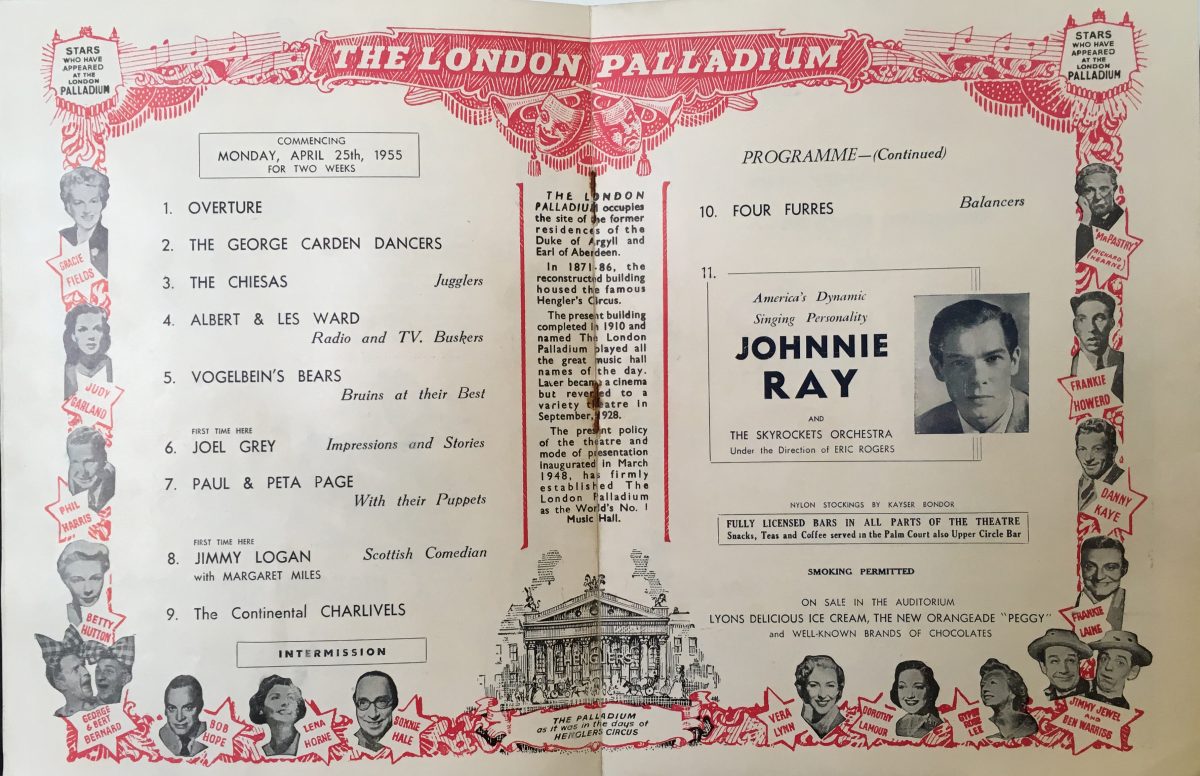

One journalist wrote that the reception was ‘the saddest and most pathetic party he had ever attended’ but Judy and Mickey at least looked as if they were having a good time. They later sat on the edge of a small stage and sang the Al Jolson song You Made me Love You together. Jolson had always been an important influence for Judy. Three months after she had signed her MGM contract in 1935, at the age of thirteen and not yet a big star, she appeared on the Al Jolson radio show. Her father, courtesy of nurses who held a radio up to his ear listened to her sing Zing! Went the Strings of my Heart shortly before he died in hospital of spinal meningitis. Sixteen years later, in 1951, she sang a Jolson medley during her four week stint at the London Palladium – her first live performances in Britain (and first anywhere for thirteen years) and for which she received £7142 a week.

It’s not strictly true that there were none of Judy’s celebrity friends at the wedding, Mickey Deans’ best man Johnnie Ray was there. Ray had recently been touring the country and in four days time he was due to perform with Judy on a Scandinavian tour that Deans had organised, anxious to make his new wife some money. Garland was severely in debt and when she returned to London at the end of 1968 some newspapers reported that she was immediately served with a writ from Harrods, who said that she owed them £145 15s 2d, a bill outstanding from October 1964.

A few weeks before the wedding, on the evening of 19 January 1969, Garland appeared on ATV’s popular The London Palladium Show. No one knew but it was to be the American star’s last ever performance on television anywhere in the world, and it went wrong from the very start. Garland was introduced by the compere Jimmy Tarbuck but the orchestra had to play for two very long minutes before she appeared on stage. Richard Stott in the Daily Mirror wrote:

Singer Judy Garland appeared to be ill last night … Towards the end of the act 46 year old Judy, who is starring at the Talk of the Town in the West End of London, seemed to have trouble pronouncing the words of towns in a song about Britain. She bent down and asked the orchestra conductor how the words of the song went! At the end of the spot, she threw her arms round Tarbuck and he helped her on to the Palladium ‘roundabout’.

A spokesman from ATV said the next day: ’she has been suffering from an attack of the flu’.

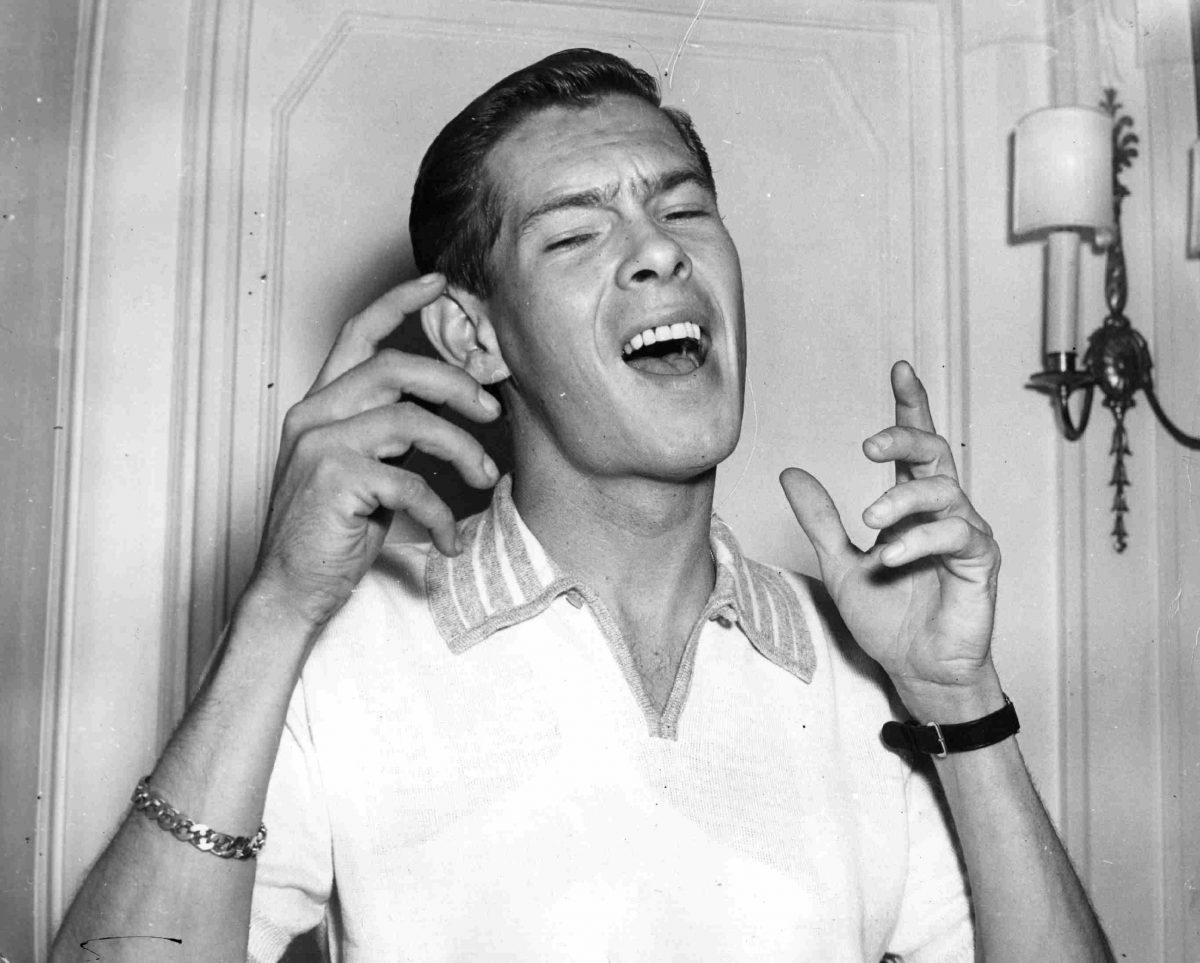

Two days later, and still feeling unwell, Garland was welcomed up on stage by Johnnie Ray, the American singer, famous for his ability to cry on stage and who had had several big hits in the UK, including Such a Night and Just Walkin’ in the Rain. That night Ray was top-of-the-bill at Caesar’s Palace, alas not the famous Las Vegas casino, but a cabaret/nightclub (sometimes spelt C’esars) situated twenty miles or so from central London in Luton, not far from junction 11 of the M1. Remembered these days mostly for his nicknames such as, ‘the Nabob of Sob’ and the ‘Prince of Wails’, the frail, almost emaciated, partly deaf American singer was still a relatively big star in Britain in 1969. Bob Stanley in his history of British pop music Yeah, Yeah, Yeah describes the Oregon-born singer as ‘arguably the most significant modern pop forbear’ and during most of the 1950s Johnnie Ray was huge. Eight or nine years before the Beatles achieved anything similar, Ray was the first star in Britain to make girls in the audience feel the need to scream continually throughout the concert (this can be heard on his 1954 album Live at the London Palladium). In September 1955, the Evening Standard reported that girls were: ‘screaming, sobbing, waving their arms and they pressed against the barriers as the singer, wearing his deaf-aid, a sports coat and open-necked shirt, was escorted from the Stratocruiser by a police superintendent. On the same flight an utterly confused Australian minister for External Affairs asked, ‘Who is this entertainer?’ The Standard wrote that for the first time since London Airport (it was renamed Heathrow twelve years later in 1967) was opened just after the war, crash barriers had to be installed outside the Arrivals Hall to keep back the ‘teenage Johnnie fans’. Four years later, in 1959, the Guardian was still reporting that Ray’s ‘emotional impact on his predominantly girlish audience was staggering.’ And that ‘amorous contortions with the microphone brought forth shrieks of delight and thunderous clapping and stamping.’

The manager of C’esar’s, the large Luton club that featured a twenty lane bowling alley on the first floor, was called George Savva – a man who did absolutely nothing to discourage the use of his nickname ‘Mr Show-Business’. In the late 1960s Savva had enough contacts to bring over not only Johnnie Ray but other transatlantic stars such as Jack Jones, Johnny Mathis and Frankie Laine. It was fair to say, however, that some of the big stars found the venue less than glamorous. Tom Jones tells a story of how Shirley Bassey once summoned Savva to her dressing room during a break in rehearsals and said: ‘are you the manager of this shit-house’? Savva nodded, to which the Welsh singer informed him that she’d refuse to perform unless the dressing room was completely re-decorated and a chaise-longue found.

It was at about this time when C’esar’s, which had up to then relied on chicken-in-a-basket and similar dishes, started to feature a more sophisticated ‘up-market’ fare. The night-club/restaurant started serving new dishes, printed in French on the menu that, according to Savva, ‘beckoned the diner seductively’ – they included:

Beef Bourgoine (sic), Cock eu Vin (sic), Canard a la Orange (sic), and lastly, and presumably after the useless translator had given up, Venison in Cherry.

Supplied by Alverston Kitchens as frozen bricks, the great advantage of these new-fangled factory foods to large club/restaurants was their almost total elimination of expensive experienced chefs. The meals came in one-portion polythene bags, which were then simply placed in boiling water for about 15 minutes before they were snipped open, emptied onto a plate and served. Although the frozen boil-in-the-bag meals were far cheaper to produce, Savva later wrote that although he knew it was wrong, ‘my greed got the better of me and I placed a £1 surcharge on the dishes.’

Meanwhile up on stage at C’esar’s Palace in January 1969, Ray was dressed in a black tuxedo and at about 11.15 pm surprised and excited the audience by welcoming Judy Garland up on to the Luton nightclub’s stage. She was wearing a very short white mini-dress with white leather boots, and to the audience looked far more fragile and thin than they remembered. Eighteen years before in 1951, the newspapers talked of Garland’s weight and the Manchester Guardian, reviewing her successful stint at the Palladium, described her as ‘a well-built girl in a lot of black chiffon’. The Daily Mail agreed, writing that her dress ‘did little to hide her almost matronly new girth’. While the Sunday Dispatch just simply went with the description, ‘plump and perspiring’ Judy told The Times at the time that it was quite simple: ‘Fat I’m happy, and thin, I’m miserable.’ Garland had been taking drugs since she was in her early teens, essentially to keep her weight down – Louis B. Mayer, the owner of MGM, called her ‘that fat kid’ (not to mention ‘my little hunchback’ – you can understand why she had trouble with self-esteem all her life) and was constantly troubled by what he saw as her weight problem. Studio doctors prescribed the new wonder drug Benzedrine, and subsequently the more sophisticated offshoots, Dexedrine and Dexamyl. Drugs like these, at that time, seemed like miracles of science and were almost as common as aspirin.

Despite the comments about her weight, the first night at the Palladium in 1951 was an absolute triumph. Even after she tripped and landed on her backside after the fourth song (the audience howled with laughter at her unfortunate mishap) the appreciation at the end of the show was extraordinary. Before she had even finished singing Somewhere over the Rainbow, her last song, the audience was so loud and effusive that Val Parnell, the managing director of the Palladium, and someone who had seen a few, described it as the biggest ovation he had ever seen or heard.

Judy Garland on stage at The Empire Theatre in Glasgow 1951 soon after her London Palladium performance

Eighteen years later at C’esars the American stars sang the song Am I Blue as a duet. At the end of which the crowd leapt to their feet and gave the two stars a five-minute standing ovation. Although George Savva described it as the most awful performance of the song he had ever heard and that the ageing superstars sang not only out of tune but out of sync. Something must have worked because he added, ‘it was also one of the most moving nights of my life.’

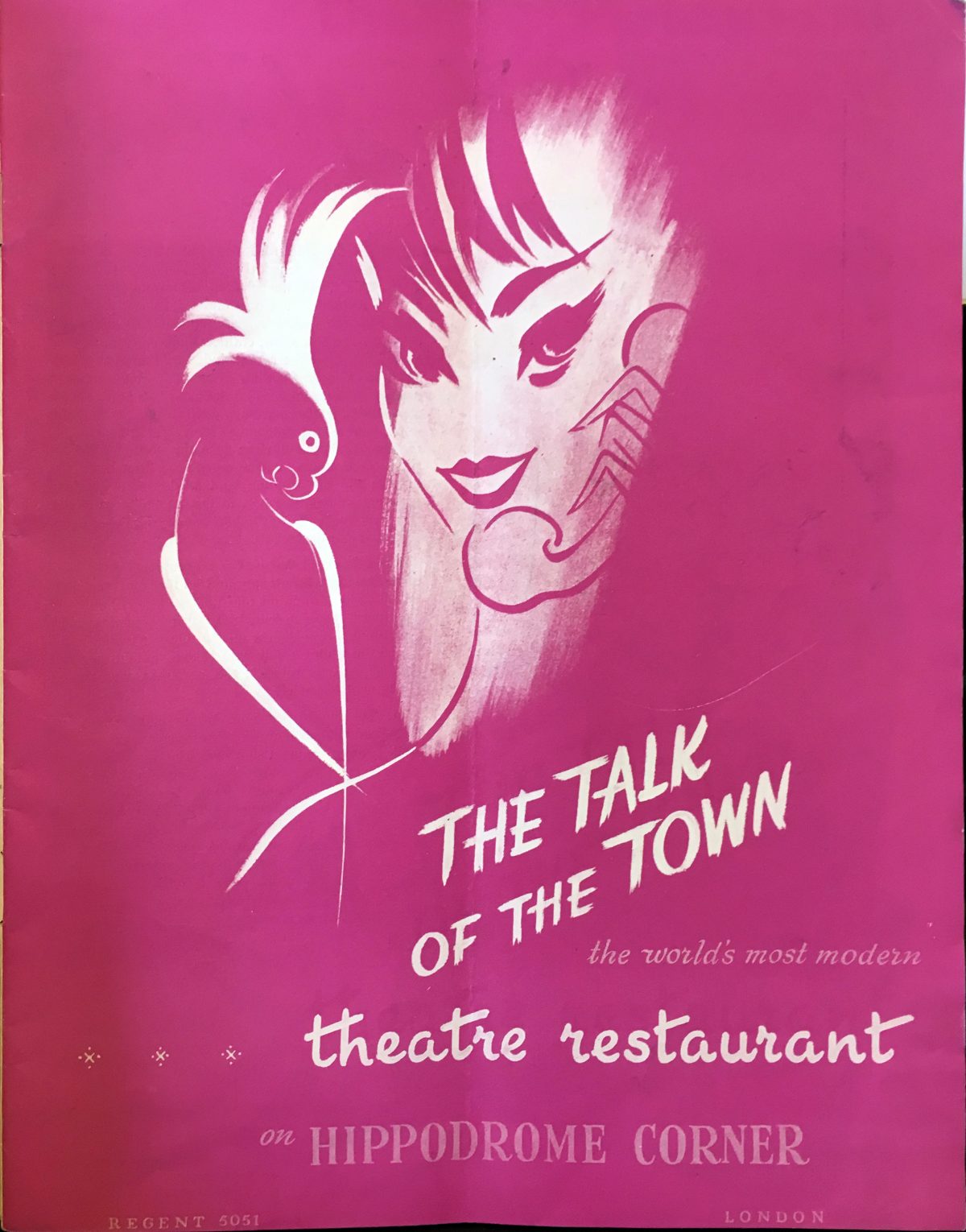

Not long after finishing the duet, Judy Garland was back in her black limo which, via the ten year old M1 motorway, drove her to her nightly show at the Talk of the Town at the Hippodrome on Charing Cross Road. She had been booked for five weeks from the very end of 1968 and her first show, on the 30 December, with Zsa Zsa Gabor, Ginger Rogers, David Frost and Danny La Rue in attendance, was a huge success. With echoes of her Palladium triumph, Bernard Delfont described the audience roaring their approval like ‘a football crowd at a cup-final’. For that first night Garland wore a bronze sequinned trouser suit, originally designed for the movie Valley of the Dolls and first worn in 1967. In Jacqueline Susann’s original book the the character Neely O’Hara, whose talent was blunted by self-destructive alcoholism and a dependency on prescription drugs, was purportedly based on Garland. The American singer had been utterly addicted to Seconal (the drug that would eventually kill her) off and on since the 1950s. Seconal, a barbiturate derivative medicine became widely misused in the sixties and had nicknames such as ‘reds’, ‘red-devils’ or ‘seccies’. Another common name for the pills, especially in California, was ‘dolls’ and thus responsible for the punning title of Jacqueline Susann’s novel – ‘Valley of the Dolls’. Judy was actually cast in the film, not as O’Hara but to play the character Helen Lawson. Not long into the filming Garland, not helped by the drug that gave the novel and movie its name, missed several days of rehearsals and she was fired in April 1967.

The Stage magazine reviewed Garland’s performance at the Talk of the Town in January 1969: ‘There are few artists who create an emotionalism – almost amounting to hysteria – minutes before they actually set foot onstage. Of these, probably the greatest is Judy.’ Tony Palmer of the Observer also wrote about her latest comeback, ‘Her survival gives her power and sex-appeal. She generates the hysteria that homosexuals, for instance, find it easy to identify with, and necessary to idolise – ‘We love you, Judy,’ shout the audience. ‘I love you, too,’ comes the response. The reviewer in Variety published a week later was perhaps more prescient; ‘Make no mistake, the Garland magic, warmth, and heart are as irresistible as ever. Nagging question is how long can Judy Garland keep it up? How long does she want to? Audience affection and goodwill are there, but there can be a limit to how long folks will watch a well loved champ gamble with her talent.’

Three weeks later the champ was gambling with reckless abandon and her performances were rapidly going down hill, with the audiences’ affection and goodwill soon dissipating. After the duet with Johnnie Ray, Garland had left C’esars about 11.30pm which, unfortunately, was exactly the time Garland was meant to be appearing on stage (Robert Nesbitt, the producer, had already put back her nightly show by half-an-hour because of her continued lateness). The crowd, despite being informed that Garland was on her way and that dancing would continue, were very restless. Judy eventually arrived at the Talk of Town at 12.50am and Lonnie Donegan, who was kept as reserve for these occasions, was stood down. Fifteen minutes later Burt Rhodes, the musical director began the overture with Judy, microphone in hand, waiting behind the curtain. The angry audience had not been told why the American singer’s show had been delayed and their impatient noise was heard in the dressing room.

When she emerged on stage singing I Belong to London, which on previous nights had always gone down well, she could barely be heard over the drunken booing and slow hand-claps. The stage was strewn with cigarette boxes and pieces of bread and Garland had to kick her way through the litter. When she began her next song The Man that Got Away the audience’s catcalls continued. At one point a red-haired man got up on stage from one of the nearby tables and grabbed Judy in one hand and the microphone in another and shouted – ‘Miss Garland! Your behaviour is disgraceful! If you can’t make it on time, why bother to turn up at all?’ At that moment a thrown wine glass smashed almost at Judy’s feet at which she burst into tears and staggered off stage. Andrew Lloyd-Webber was in the audience during Judy’s short performance that night and it inspired him to write, a few years later, Don’t Cry For Me, Argentina.

By the end of January and three weeks into the engagement, Bernard Delfont realised that Garland was now unwell and unable, realistically, to continue with her booking. ‘I’m sorry, Judy. I can’t let you go on unless you let me have a doctor’s certificate to say you are fit’ he ended up telling her. A headline the next day said ‘Delfont Bans Judy Garland’, but he knew that he was now dealing with a very sick woman ‘brought low by twenty years of drink and drugs’. Much to Delfont’s surprise, however, her doctor, John Traherne, confirmed unequivocally that Judy Garland was able to perform the rest of the engagement. Which, after a weekend off to try and shake off her flu-like symptoms, she did. The time-keeping didn’t improve and on most nights Delfont noticed that whatever was left from the pre-show meal usually ended up on the stage. At this stage of her life Garland was taking a cocktail of drugs just to keep on going. She hardly ate at all and, unsurprisingly, was nearly always unwell. Mickey Deans later wrote about this time:

During the last two weeks of the Talk of the Town engagement, when she was physically so drained by the flu, she took enormous amounts of Ritalin in order to perform and large doses of Seconal to lull her to sleep. When she suffered from a kind of malaise of spirit, the combination of Ritalin and Seconal taken together produced an instant high. Judy, of course, took Ups early in the evening before a performance and more, if she were sagging physically, during the performance. The drug killed her appetite, made her sick to her stomach and increased her pulse rate. She sometimes took another drug when she felt her heart was beating too fast.

The last of Garland’s Talk of the Town performances took place on 1 February 1969. She left the club at 2am, and when she signed a fan’s magazine outside the stage door she first covered the eyes, and then her mouth on the cover photo with her hand and said, ‘See? The mouth smiles…but the eyes do not.’ Not long after her final performance, Garland and Mickey Deans moved from the Ritz hotel into a small mews house on a Chelsea cul-de-sac called Cadogan Lane. Judy had already lived in Chelsea for a short while late in 1960 when she lived in a house owned by Sir Carol Reed in King’s Row. Her children, Joey and Lorna, went to Lady Eden’s School in Kensington and ‘Liza was enrolled at a tutorial school on Victoria Street’. The Cadogan Lane house was later described by Mickey Deans as a ‘modest little mews house with six cozy intimate rooms. A white stucco house with a yellow front door and a cement flower box that ran its length.’

The front door of the house opened directly into a living room that had white walls, grey carpeting, and a sofa and chairs upholstered in black and white ticking. The dining room had red walls a round table under a skylight and a matching ‘buffet and sideboard’. The main bedroom had a chest of drawers, two small chairs, a dressing table and two large wardrobes. Judy and Mickey added lamps coloured sheets and a bright blue ‘chintz’ bedspread. The bedroom alongside, which became Judy’s dressing room, was painted a warm pink with a green Tiffany lamp and rose coloured carpeting. Across the hall from the bedroom was a ‘large sallow-green’ tiled bathroom that had a window through which you could see the skylight of the kitchen. On the turn of the staircase was a large rubber tree in a tub.

After their March wedding, Garland and Deans flew to Majorca for a brief honeymoon, but quickly transferred to Paris where they stayed at the Georges V hotel. Three days after the wedding, they flew to Stockholm for the short Scandinavian tour with Johnnie Ray. Her last public appearance in London was on 18 June 1969, when she was picked up at 9pm by her neighbours Gina Dangerfield and Richard Harris (an interior designer and not the actor) and taken to Bromley for the opening of Jackie Trent and Tony Hatch’s ‘grand opening’ of their new menswear shop. Four days later, on Saturday 22 June, just three months after their wedding, Judy and Mickey had been watching a BBC documentary on the Royal family but as both felt unwell they went to bed early. At around 10.40am the next morning the phone rang for Garland. Deans got up and found the bathroom door locked. He climbed out on to the roof and looked through the window and saw Garland motionless on the toilet with her head slumped forward and her hands on her knees. Climbing into the bathroom, he found her skin was discoloured and dried blood had dribbled from her mouth and nose. She had been dead for about eight hours. A bottle containing 25 barbiturate pills was later found by her bedside half-empty, and another bottle of 100 was still unopened. It was twelve days after her 47th birthday.

The Chelsea Coroner, Gavin Thurston, wrote, ‘This is a clear picture of someone who had been habituated to barbiturates in the form of Seconal for a very long period of time, and who on the night of June 22nd/23rd perhaps in a state of confusion from a previous dose (although this is pure speculation) took more barbiturate than her body could tolerate.’ Garland two years earlier had spoken of Marilyn Monroe’s death and predicted her own, ‘You take a couple of sleeping pills,’ she had explained, ‘and you wake up in twenty minutes and forget you’ve taken them. So you take a couple more, and the next thing you know you’ve taken too many.’ Ironically, considering the effort she put into keeping her weight down for most of her life, Garland was probably less than 70 pounds when she died. She was so thin that when her body, covered in only a blanket, was removed from the Cadogan Lane mews house it was said she was carried out draped over someone’s arm like a folded coat. Deans took Garland’s remains to New York City on June 26, where an estimated 20,000 people lined up to pay their respects at the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel in Manhattan. The funeral the next day was paid for by Frank Sinatra (Garland was $4 million in debt when she died) and the eulogy was read by James Mason. Her Wizard of Oz co-star, Ray Bolger, commented at the funeral, ‘She just plain wore out.’

A few weeks after the funeral Allan Warren, actor and occasional wedding photographer, met Mickey for lunch at his New York apartment:

He never got off either of the two telephones he was talking on, for nearly two hours. The room was piled high with Judy Garland memorabilia that he was auctioning off. When he did get off the phone he shouted over the desk. “Did you bring the negatives from England.?” I I said ‘no’ – he was furious as he said he could have sold them. I never did get lunch, or ever see him again.

Johnnie Ray, a gay man who was never in a position to acknowledge, publicly, his sexuality, suffered from alcoholism throughout his life. After he was hospitalised with tuberculosis in 1960 he stopped drinking and for a few years was in a long-term relationship with his manager Bill Franklin, a man thirteen years his junior. In 1969, not long after his friend Judy had died, an American doctor told Ray he was now well enough to enjoy the odd glass of wine. It was bad advice, the heavy drinking resumed and he never really recovered. Ray died of liver failure in 1990 and is buried in Hopewell, Oregon.<

Five years after Garland’s death, Johnnie Ray was still performing Am I Blue, the song he sang with Garland on stage at C’esars in Luton, as a sort of ‘duet’. Barry Coleman of the Guardian reviewed a 1974 Johnnie Ray concert in Chorley:

‘the spotlight on the absent, not to say dead, Judy’s stool seemed a bit much. But that, as sure as hell, is showbiz.’

This post is an excerpt from Rob Baker’s acclaimed London history book High Buildings, Low Morals.

High Buildings, Low Morals published by Amberley Publishing.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.