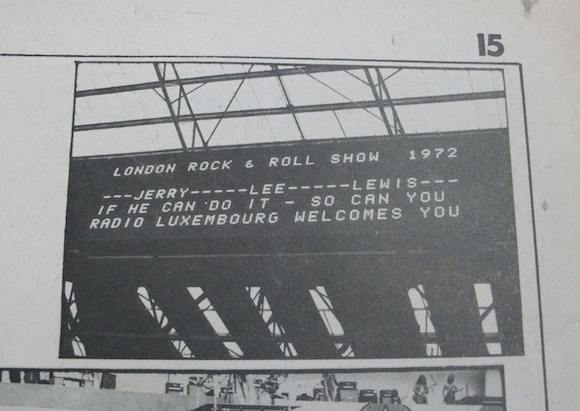

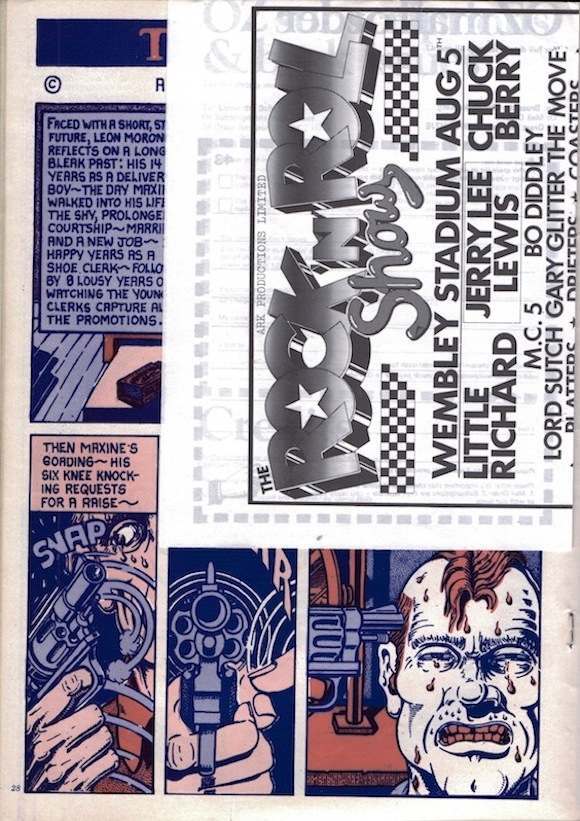

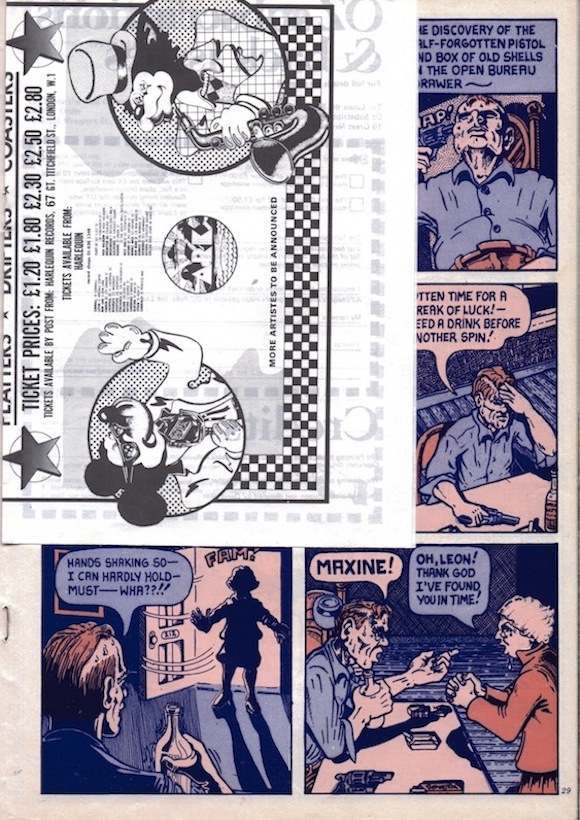

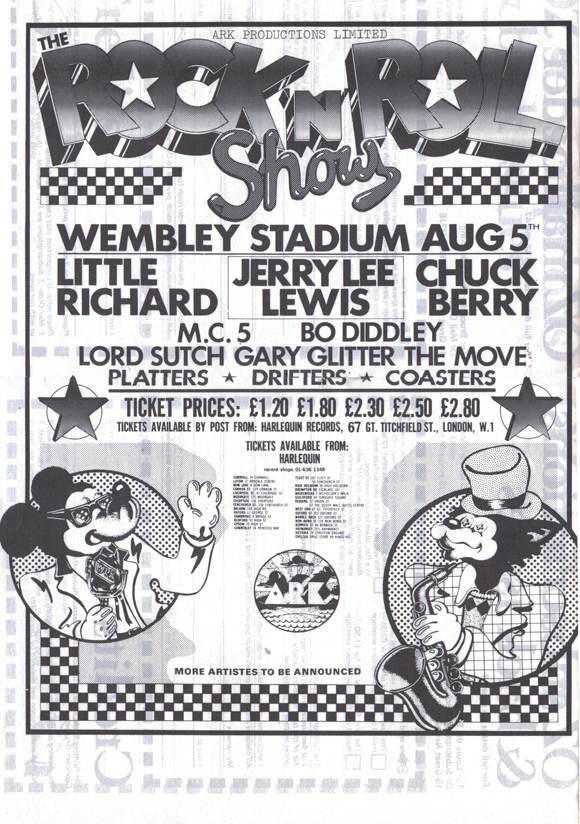

Flyer for The Rock n Roll Show printed on the back of a subscription form for Oz magazine, July 1972.

I acquired my first underground press publications in the summer of 1972, at about the point when the sector was taking the nosedive from which it never recovered.

Still, better late than Sharon Tate, as they say. Aged 12, my taste had been whetted by sneak peeks at an older brother’s collection of magazines when a guy called Kevin O’Keefe who lived down the road gave me a few copies of Oz, including number 43, the July issue.

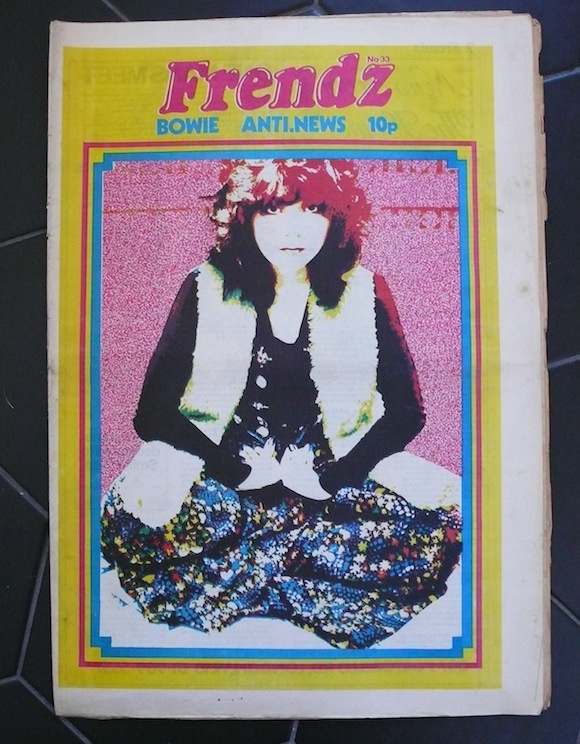

A few weeks later, to my astonishment, the newsagents in Hendon’s Church Road started stocking Frendz. I folded issue 33 between a couple of music papers and pored over it in my bedroom.

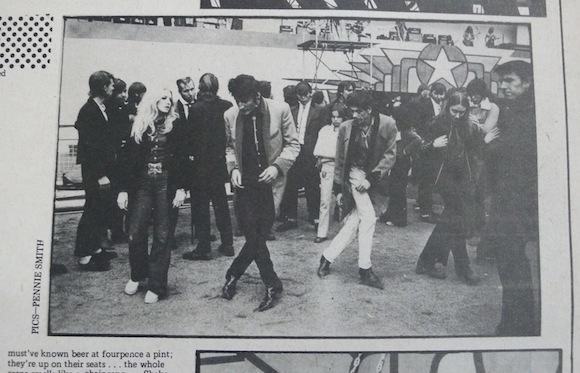

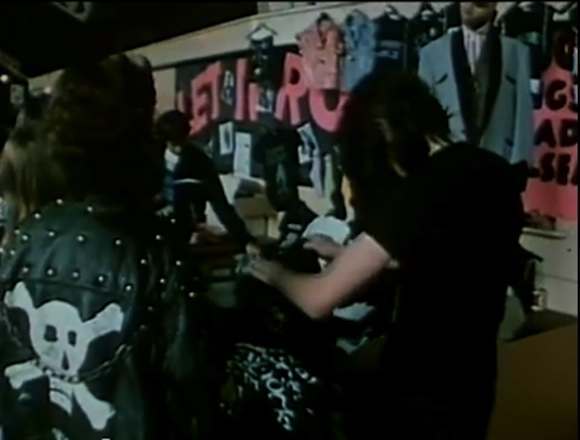

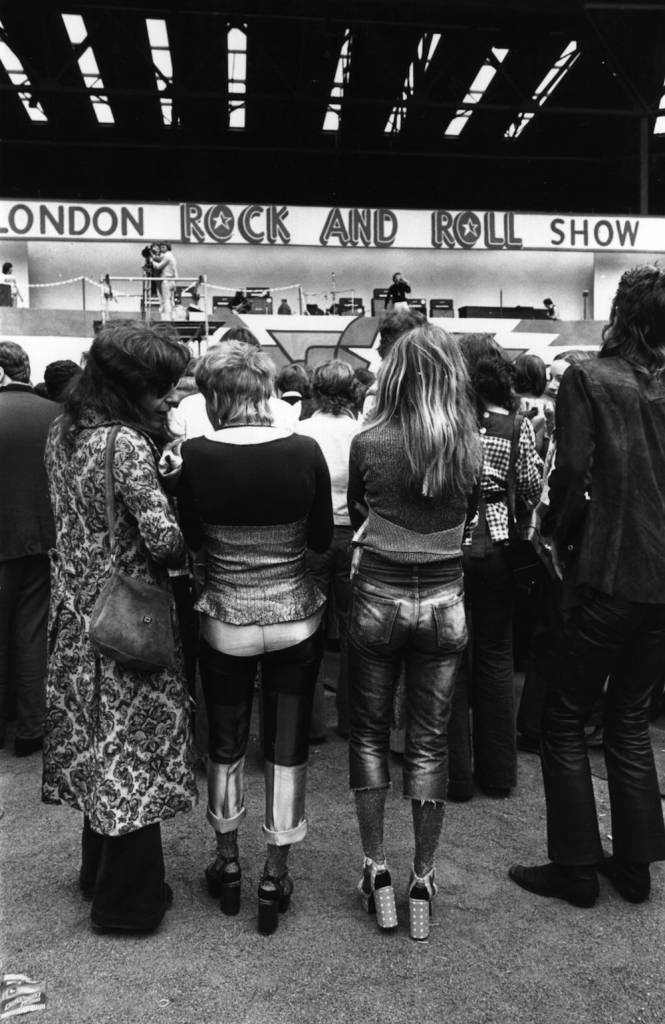

Crowds around the Let It Rock stand. From the 1973 film London Rock N Roll Show directed by Peter Clifton

Neither of the magazines are shining examples of the genre, but they had something in common: the centre spread of OZ 43 contained a subscription form back-printed with a flyer for the London Rock N Roll Show, a one-day festival of original 50s acts and those who could claim kinship held at Wembley Stadium on August 5 that year.

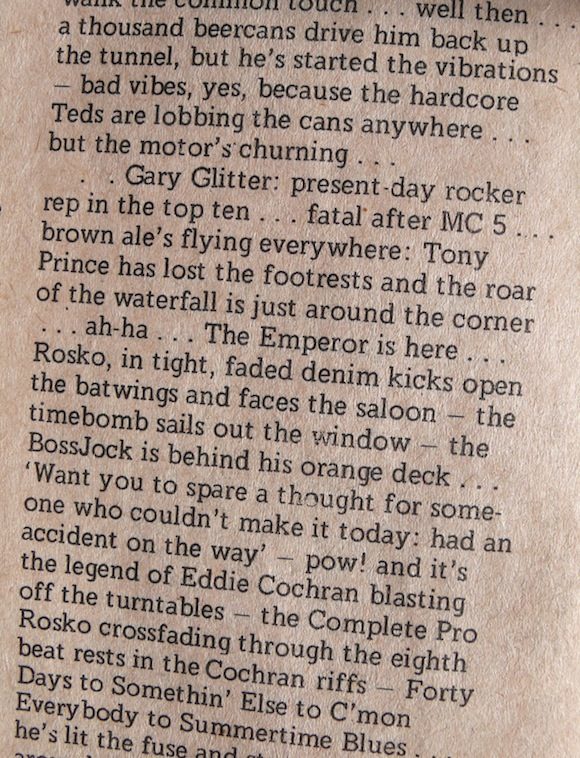

And for me the most beguiling article in Frendz 33 was a two-page stream-of-consciousness report of the event filed by one Douglas Gordon and illustrated with photographs by Pennie Smith, soon to leave for the NME and carve out her reputation as one of rock photography’s all-time greats.

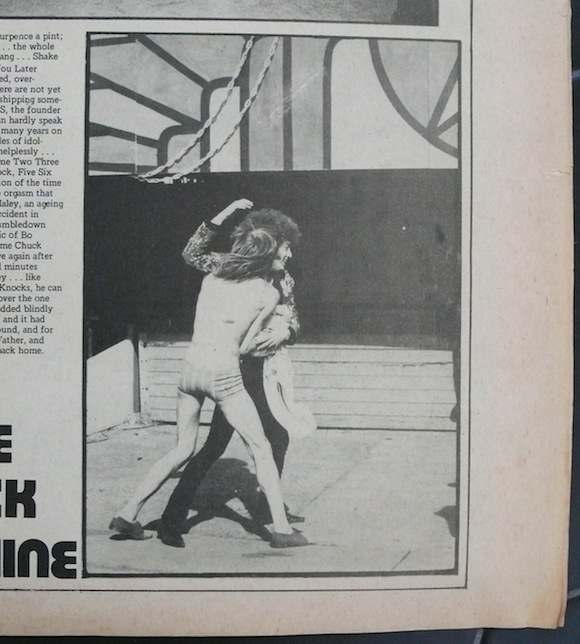

Superfan “Jesus” dances to MC5 guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith, who appeared on stage in a superhero costume and silver-painted face. Photo: Pennie Smith

5th August 1972: A group of teddy boys dancing at the London rock ‘n’ roll revival show in Wembley Arena.

The event was held just a couple of miles west of where my family lived. Our next door neighbour’s son – who played in London Teddy Boy band Flying Saucers Rock N Roll – went to the show but he didn’t give much away when quizzed as he washed his blue Ford Consul of a Sunday.

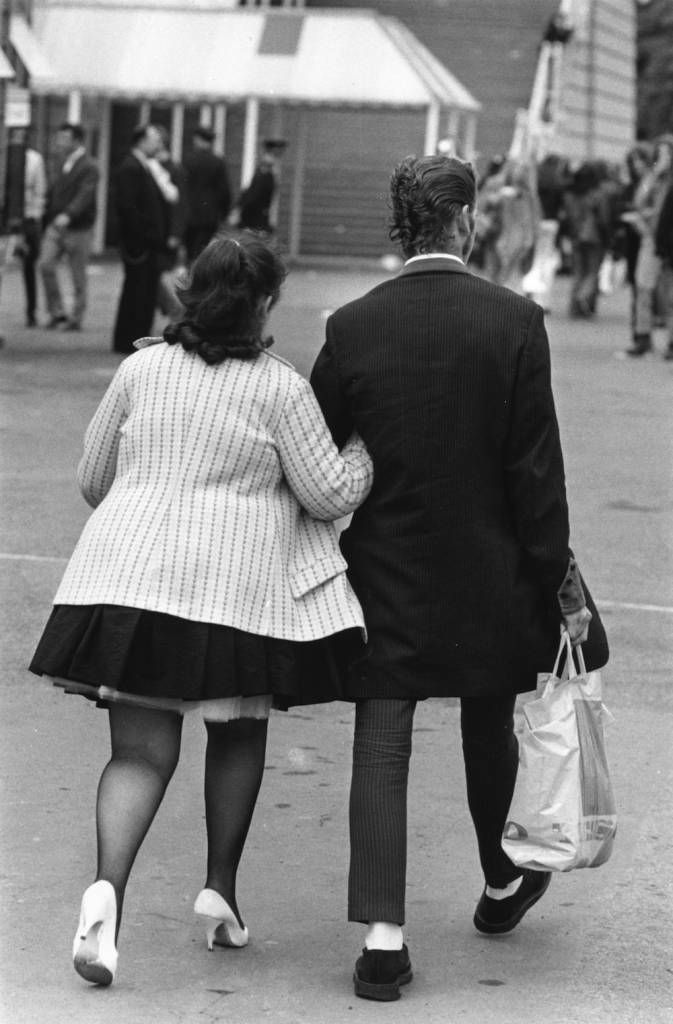

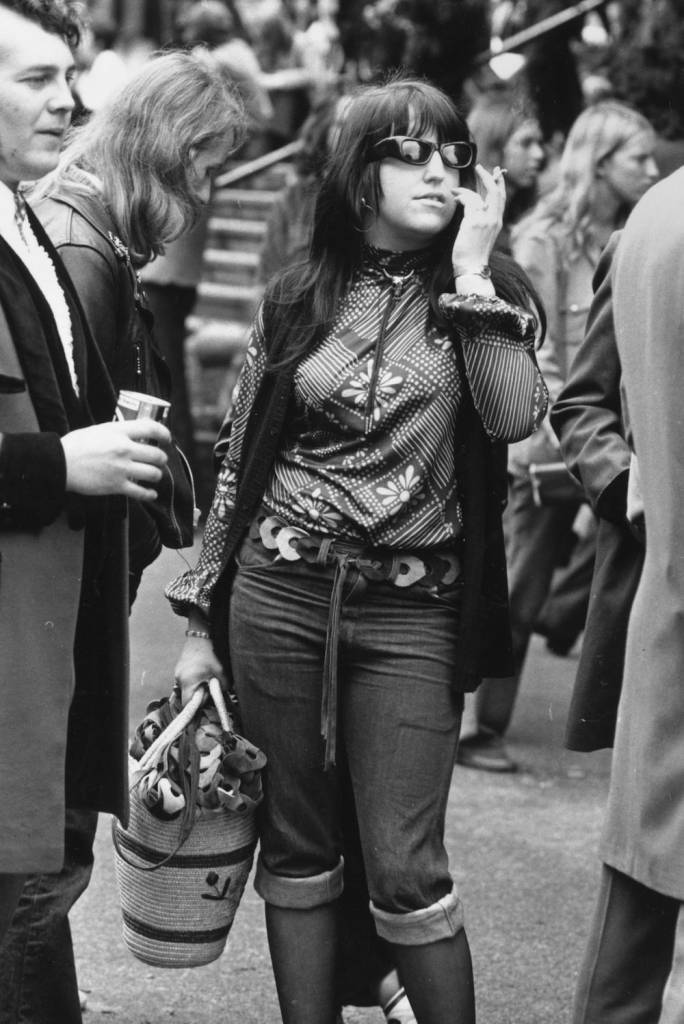

August 1972: Rock ‘n’ roll fans who attended the Rock ‘n’ Roll Festival at Wembley, North London. (Photo by Evening Standard/Getty Images)

Australian film-maker Peter Clifton’s 1973 film of the show is a marvellous document, with interviews with participants and attendees including Mick Jagger. Clifton also captured the crowd around the stall taken at the show by Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s King’s Road outlet Let It Rock, which had made the special edition of the capital’s daily paper the Evening Standard under the heading “The Teds Are Back”.

“Here it is, London’s first ever rock’n’roll shop, sited of all places in the middle of Chelsea’s boutique strip,” wrote Geoffrey Aquilina Ross.

Make up artist Yvonne Gold was a teenage habituée of the World’s End fashion stores, and recruited by McLaren to help out on the Let It Rock stall at Wembley. In one sequence in Clifton’s film she can be seen with McLaren dealing with customer demand.

‘We got there quite late and there was a kerfuffle about setting up,” she recalls. “It was quite at first, until the word got around and then we were overwhelmingly busy, even though there were quite a few of us manning that stall. The t-shirts just flew; we took a lot of money.”

1972: A woman standing next to a teddy-boy sells leather belts at the Rock n’ Roll Festival, Wembley Stadium. (Photo by Evening Standard/Getty Images)

As confirmed by my own conversations with McLaren, the Wembley event represented a turning point away from pure revivalism for he and Westwood as they investigated the fetishistic bricolage approach of the clothes worn by early 60s Ton Up boys and girls which formed the basis of the next incarnation of 430 King’s Road, Too Fast To Live Too Fast To Die.

Sleeping youth in UA Records Fats Domino Rock N Roll Is Here To Stay t-shirt. Still from Peter Clifton’s London Rock N Roll Show

“This was where Malcolm was starting to introduce decorated leatherwear,” confirms Gold. “He really had his finger on the pulse and the rocker thing started to come in at Wembley because it was much sexier.”

Hippies and rockers together at the rock ‘n’ roll Revival Show, held at Wembley Stadium, London. (Photo by Michael Webb/Getty Images)

Prominent vintage fashion retailer Ian Johns – who runs east London’s Hunky Dory with his partner Ian Bodenham – was in the crowd, a 15-year-old who had been introduced to the rock n roll nights which had driven the 50s revival in preceding years at The Railway pub in Harrow, north west London.

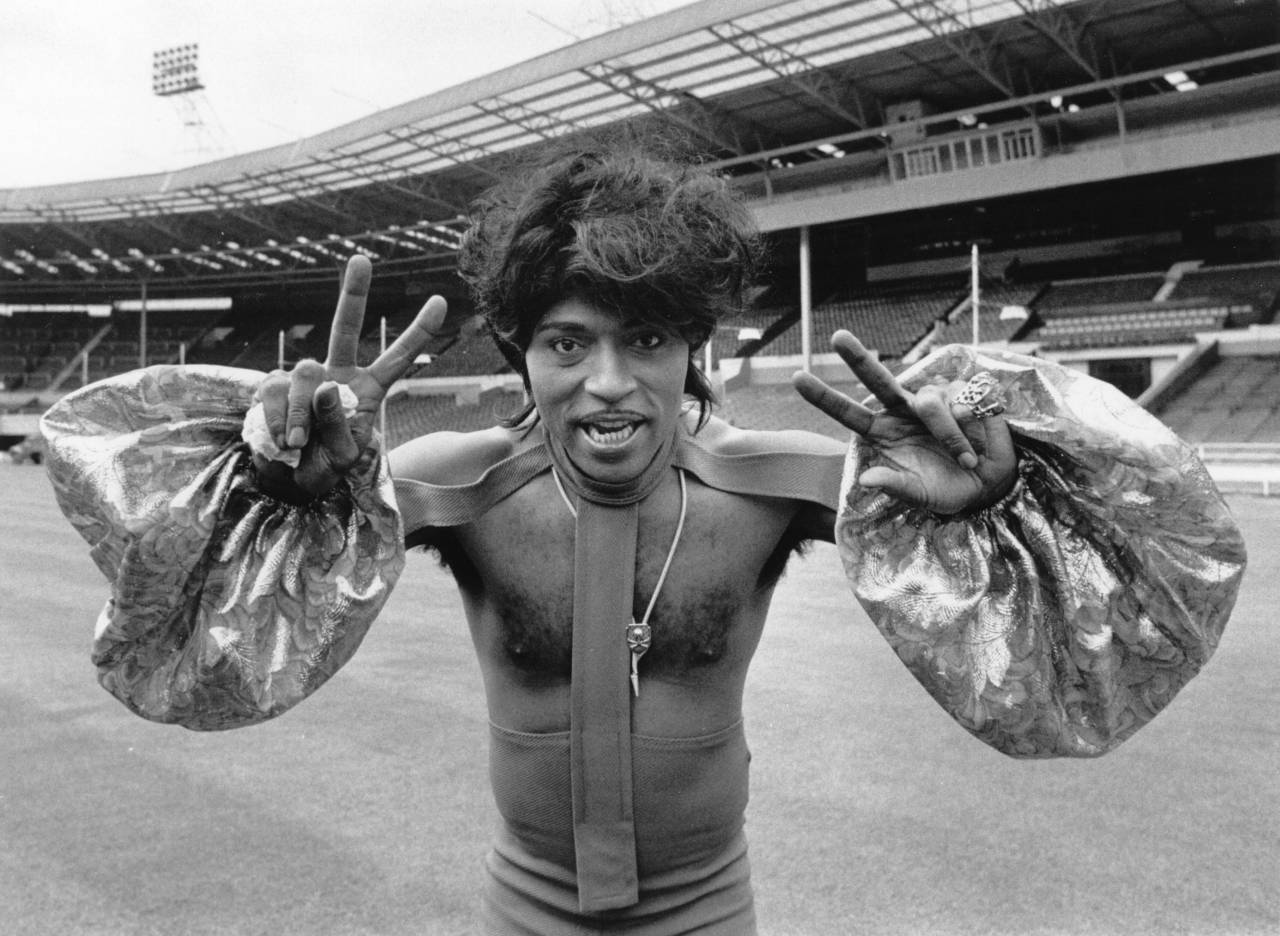

“I’m pretty sure I saw flyers for the show at Let it Rock, ” says Johns. “About six of us slept outside Wembley to make sure we got in, but as it turned out, there wouldn’t have been a problem. I clearly remember the LIR stall, and Malcolm working on it. There were loads of Teds, Angels, greasers, rockers and even hippies. Gary Glitter was bottled off, I remember Wizzard and Heinz, the MC5, most of it really, and was part of the invasion of the pitch area. Lord Sutch was great, Chuck Berry probably best and Little Richard fab. That was when I realised he must be gay! I nearly got a platform boot he threw into the audience.”

3rd August 1972: Rock ‘n’ roll legend Little Richard in costume at an empty Wembley Stadium, during rehearsals for a concert. (Photo by Tim Graham/Evening Standard/Getty Images)

“Jerry Lee was really good, but late,” says Johns. “They said he had been hanging out at (City Of London Ted haunt) The Black Raven where some Teds had told him that if he played any country music they would boo him off. The sound was good as far as I remember, and being only 15 it was a fantastic gig, one I will always remember.”

I recommend Clifton’s film highly – copies available here.

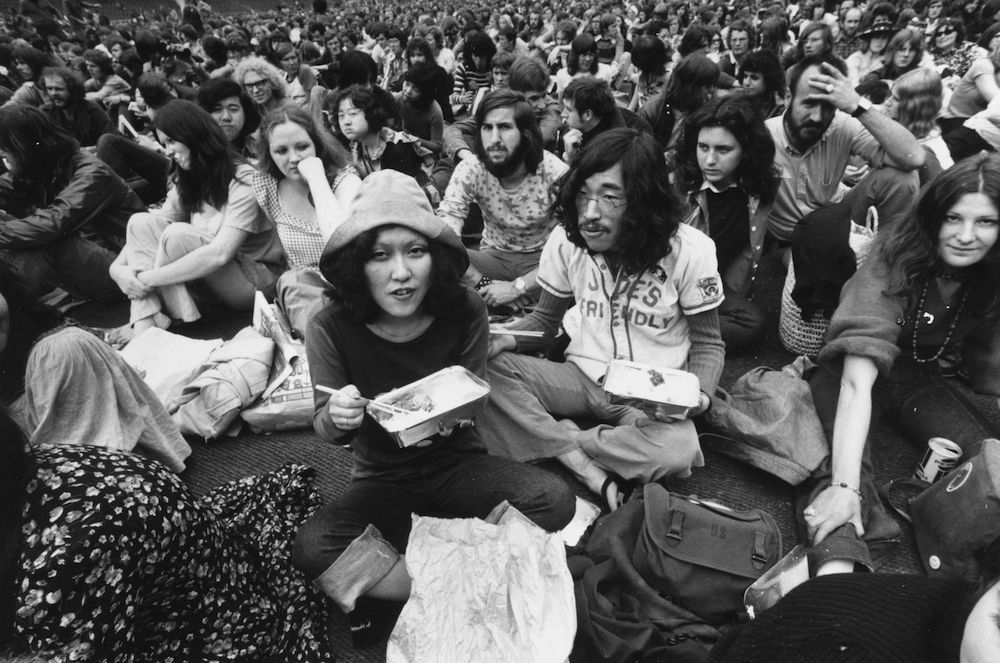

August 1972: Japanese hippies amongst the large crowd at the Rock ‘n’ Roll Festival at Wembley Stadium, London. Among them is Mei Wei.

Teddy Boys, hippies, Rockers and Hell’s Angels gathered at Wembley Stadium for a Rock ‘n’ Roll revival show, 5th August 1972.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.