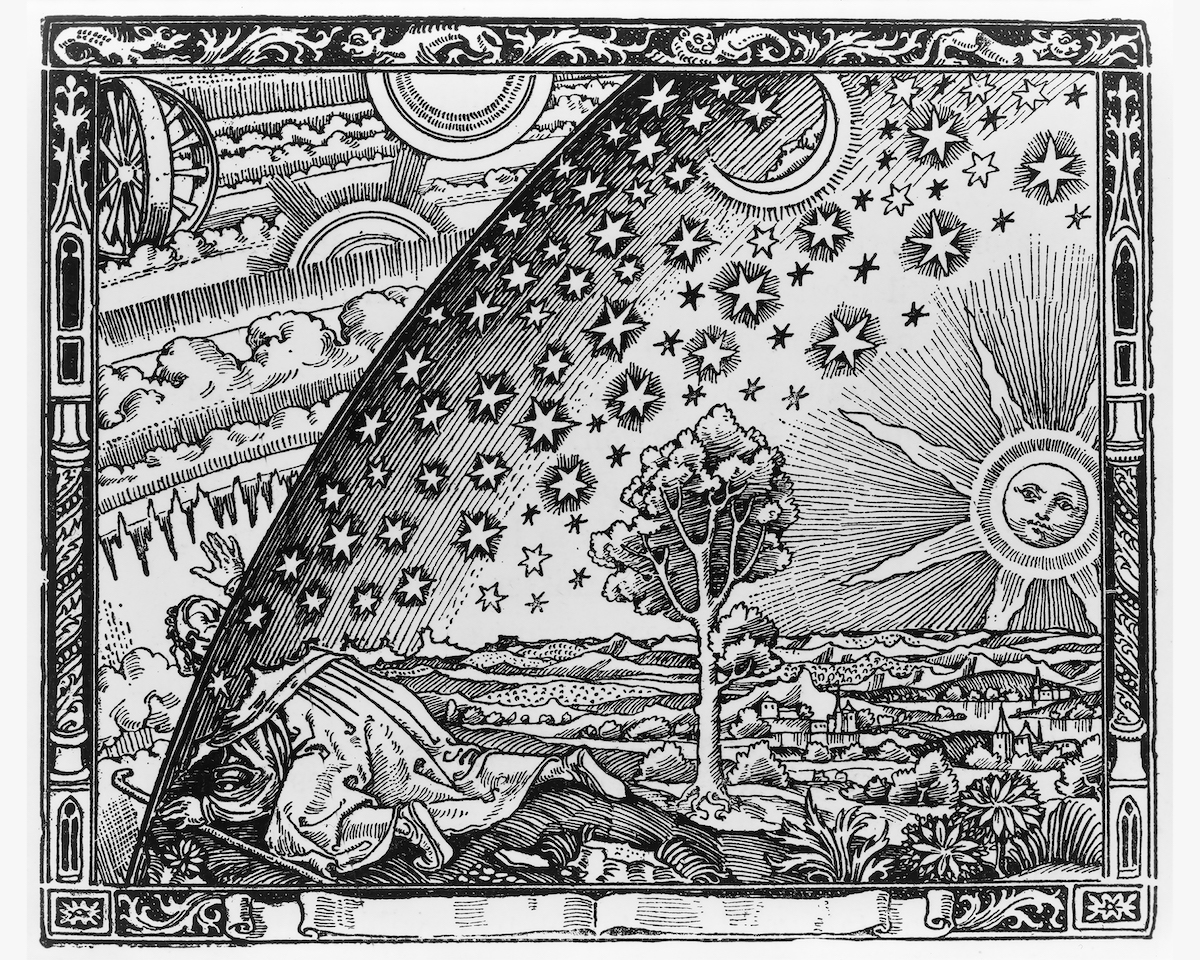

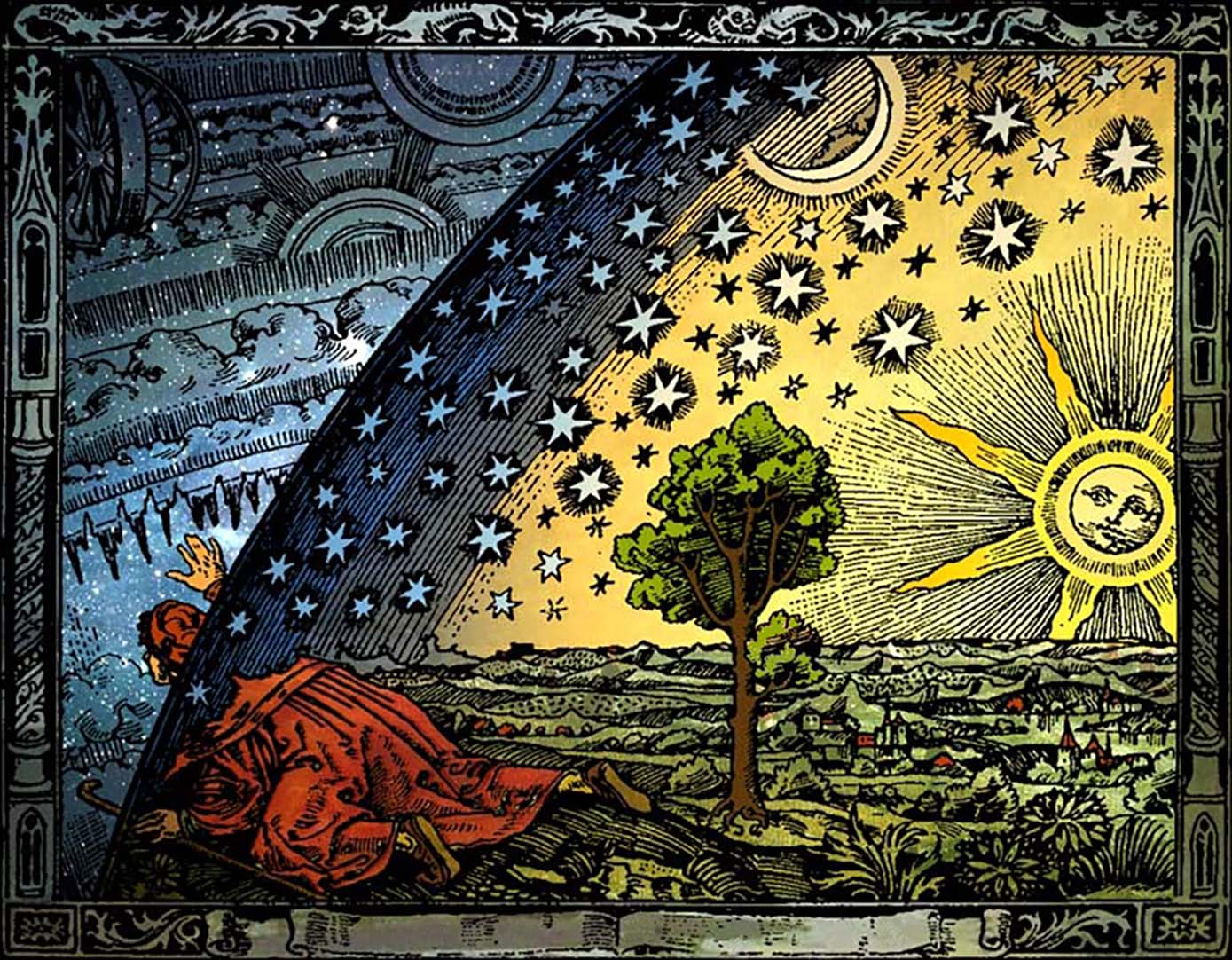

The so-called ‘Flammarion engraving’ is a wood engraving by an unknown artist that first appeared in French writer Camille Flammarion’s L’Atmosphère: Météorologie populaire (1888) in a chapter called ‘The Shape of the Sky’.

The image is of a man crawling under the edge of the sky, depicted as if it were a solid hemisphere beneath which all life is encased, to look at the mysterious Empyrean beyond (that medieval cosmology placed beyond the sphere of fixed stars).

Behind the sky, the pilgrim finds a marvellous realm of circling clouds, fires and suns. One of the elements of the cosmic machinery resembles traditional representations of the “wheel in the middle of a wheel” described in the visions of the Jewish prophet Ezekiel.

The caption underneath the engraving reads:

“Un missionaire du moyen âge raconte qu’il avait trouvé le point oû le ciel et la Terre touchent” (English: “A medieval missionary tells that he has found the point where heaven and Earth meet.”)

Opposite, the following text accompanies the image:

“What is there, then, in this blue sky, which certainly exists, and which veils the stars from us during the day?

Flying Sauers And Other Things

Hans Holbein the Younger, Ezekiel’s vision of God, the four living creatures, and a wheel within a wheel, published in Historiarum veteris instrumenti icones ad vivum expressae (1538).

When the engraving was created is uncertain. If it is a Medieval or Renaissance artwork surely it would have featured in earlier texts. So it’s more likely to be an illustration that borrows older artistic styles and themes.

Some authors, following art historian Erwin Panofsky, date it to the 16th century; others, following Ernst Gombrich, to the late 19th century.

Psychoanalyst Carl Jung, in his 1959 book Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies, says the image could be from a Rosicrucian engraving from the 17th century. He focuses on the ‘wheels of Ezekiel’, the interlocking double wheel in the top left corner of the image, toward which the pilgrim is pointing:

This 17th century engraving, possibly representing a Rosicrucian illumination, comes from a source unknown to me. On the right it shows the familiar world. The pilgrim, who is evidently on a pilgrimage, has broken through the star-strewn rim of his world and beholds another, supernatural universe filled with what look like layers of cloud or mountain ranges. In it appear the wheels of Ezekiel and rings or rainbow-like figures, obviously representing the “heavenly spheres.” In these symbols we have a prototype of the UFO vision, which is vouchsafed to the illuminati. They cannot be heavenly bodies belonging to our empirical world, but are projected “rotunda” from the inner, four-dimensional world.

We don’t know who recreated the Flammiron engraving or when. The other debate is around what it all means.

Searching For Synchronicity in the Flammarion Engraving

Bruno Weber and Joseph Ashbrook argued that the Flammarion engraving’s depiction of a heavenly vault separating a flat Earth from an outer realm may have been inspired by this woodcut from Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia of 1544.

Is the relationship between the events random or is some hidden force actively at work? It’s something Laurence Brown considers in his thesis The Flammarion Engraving and its Symbolic Potential, which appeared in Psychological Perspectives A Semiannual Journal of Jungian Thought in October 2021.

In 1952, during an interview with the religious historian Mircea Eliade, Jung described synchronicity as a “rupture of time” that “closely resembles numinous experiences in which space, time and causality are abolished”. It’s a coincidence in which the meaning is immediately apparent and differences between inner psychological states such as dreams, fantasies, or feelings and the outer or material world vanish, allowing the timeless to stream through.

As Brown writes, “Flammarion was also a great champion of the paranormal, which, unlike today, was not at all unusual for respected scientists. In 1900, he published a book titled L’inconnu (The Unknown), in which featured the superb story of M. de Fortgibu and the plum pudding. Jung quotes this story with great delight in his main essay on synchronicity, the term he coined for meaningful coincidences”:

A certain M. Deschamps, when a boy in Orleans, was once given a piece of plum pudding by a M. de Fortgibu. Ten years later he discovered another plum pudding in a Paris restaurant, and asked if he could have a piece. It turned out, however, that the plum-pudding was already ordered – by M. de Fortgibu. Many years afterwards M. Deschamps was invited to partake of a plum pudding as a special rarity. While he was eating it he remarked that the only thing lacking was M. de Fortgibu. At that moment the door opened and an old man in the last stages of deterioration walked in: M. de Fortgibu, who had got hold of the wrong address and burst in on the party by mistake.

Also in L’inconnu, Flammarion describes a personal coincidence that occurred to him as he was writing L’Atmosphère: Météorologie populaire. He was writing about “the strange doings of the wind” when a sudden gust blew his work off the table and out of the window, “carrying them off in a sort of whirlwind among the trees” . It started to rain, so Flammarion decided it would be a waste of time to go and look for them. A few days later, the printer delivered that exact chapter to Flammarion, without a page missing. In uncanny valley a porter from the printing office, who lived nearby and regularly worked on Flammarion’s publications, had spotted the papers. Thinking that he must have dropped them himself, the porter had picked them up and taken them to the printing office.

Away From Duality: The Sublime Harmony of All Things

.

Synchronistic occurrences mark the magical moment when the duality of soul and matter seems to be undone. “They are,” says Brown “therefore an empirical indication of an ultimate unity of all existence, which Jung, using the terminology of medieval natural philosophy, called the unus mundus. ”

Jung’s unus mundus (one world) centres on the unity of the world where mind and matter are not yet separated, forming the underlying condition of our existence. It was also his view that when synchronistic events occur, the unus mundus breaks through into the consciousness of the person experiencing it.

As Flammarion writes:

Whether the sky be clear or cloudy, it always seems to us to have the shape of an elliptic arch; far from having the form of a circular arch, it always seems flattened and depressed above our heads, and gradually to become farther removed toward the horizon. Our ancestors imagined that this blue vault was really what the eye would lead them to believe it to be; but, as Voltaire remarks, this is about as reasonable as if a silk-worm took his web for the limits of the universe. The Greek astronomers represented it as formed of a solid crystal substance; and so recently as Copernicus, a large number of astronomers thought it was as solid as plate-glass. The Latin poets placed the divinities of Olympus and the stately mythological court upon this vault, above the planets and the fixed stars. Previous to the knowledge that the earth was moving in space, and that space is everywhere, theologians had installed the Trinity in the empyrean, the glorified body of Jesus, that of the Virgin Mary, the angelic hierarchy, the saints, and all the heavenly host…. A naïve missionary of the Middle Ages even tells us that, in one of his voyages in search of the terrestrial paradise, he reached the horizon where the earth and the heavens met, and that he discovered a certain point where they were not joined together, and where, by stooping his shoulders, he passed under the roof of the heavens…

Touching Eternity

Marie-Louise von Franz (4 January 1915 – 17 February 1998), a Swiss Jungian psychologist and scholar, known for her psychological interpretations of fairy tales and of alchemical manuscripts, loved the image. In her work Number and Time: Reflections Leading toward a Unification of Depth Psychology and Physics, Flammarion’s engraving is a pictorial metaphor for synchronicity. She commends our attention to the symbolic significance of the open hole in the fabric of the known world and the functionally untenable double wheel.

Von Franz viewed “hole open to eternity” as rooted in medieval alchemy, in particular the work of 16th century alchemist Gerhard Dorn, who in his writings referred to the spiraculum aeternitatis. As von Franz explains: “Spiraculum is an air hole, through which eternity breathes into the temporal world”.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.