On the 20th anniversary of the Soviet Union’s collapse, historian Richard Sakwa wrote of “a triumphalist discourse” in the U.S. “which suggests that the Soviet demise was a deliberate act plotted and executed by president Ronald Reagan.” The parts of his ingenious master plan included “engineering lower oil prices… launching the Star Wars initiative” and “arming the mujahedeen in Afghanistan with Stinger rockets.”

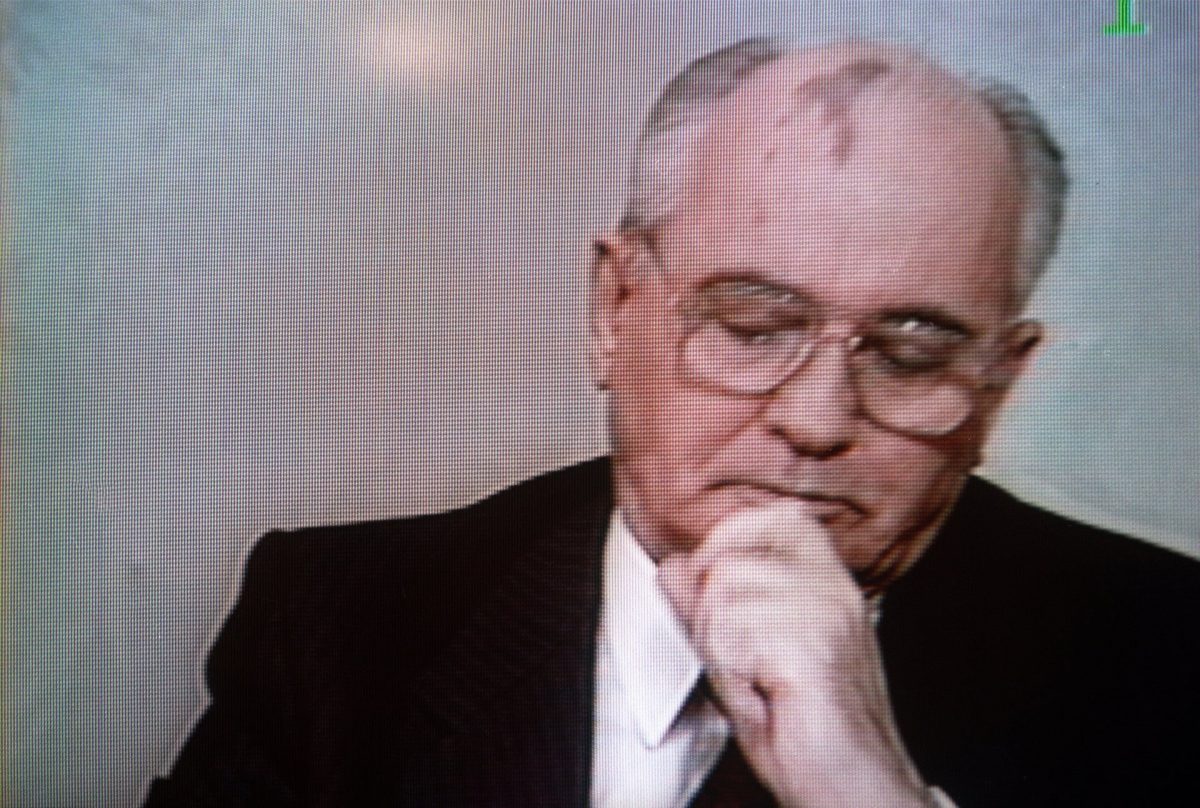

After nearly thirty years, this narrative has worn a little thin. Among other things, it fails to account for the degree to which the Soviet Union was dismantled from within, with little need for Western intervention, by its eighth leader Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, the last general secretary of the Communist Party, who was either, depending on one’s perspective, “a magnificent failure” or a “tragic success,” or both.

Appointed General Secretary in March of 1985, Gorbachev aimed to “carry out a root-and-branch reform of the Soviet system,” the University of Luxembourg notes, “the bureaucratic inertia of which constituted an obstacle to economic restructuring (“perestroika”), and, at the same time, to liberate the regime and introduce transparency (“glasnost”), i.e. a certain freedom of expression and information.”

These were not new ideas. “Stalin occasionally had used [the words] as had his successor,” Lewis Siegelbaum points out. “Both terms can be found in Gorbachev’s speeches and writings as early as the mid-1970s.” Their familiarity may explain why Gorbachev’s announcement of his program at the 27th party congress in 1986 (above) met with a comparatively anaemic response from Party leaders at first. They’d heard it all before.

It would take several more years, after restructuring introduced a market economy to the USSR with famously disastrous results for ordinary Soviets, before conservative Communist Party members formulated a response, organizing a conference in Leningrad in October, 1990 to draft a resolution expressing a “lack of confidence in the policies of the General Secretary.” By this time, a revolution was already underway, begun in 1989 with the fall of the Berlin wall and the successive demands from Soviet republics for sovereignty and independence.

Sakwa points out that “President George H. Bush sought to keep the Soviet Union together” at this point, fearing the chaos that would result from its collapse. That collapse came swiftly as the country began “reforming itself out of existence” by seeking to maintain the outward appearance of a Communist state while increasingly abandoning its commitments to communism.

Gorbachev had indicated his willingness to make “Faustian bargains” with Western leaders even before coming to power. In 1984, Soviet miners donated over a million dollars to their striking British counterparts. Berated by Margaret Thatcher, who wanted to crush the British miner’s union, Gorbachev denied all knowledge of the event, “though a month earlier he had personally signed the papers authorizing the transaction. In the end Gorbachev decided the cultivating the British government… was a price worth paying.” After their first meeting, Thatcher declared him a leader she “can do business” with.

Reforms instituted quickly, with little efficient planning, lead to “an extended bank run,” Sakwa writes, “in which the state was ‘stolen.’” Governance quickly disintegrated” as new forms of corruption set in. But the contradictions that led to what many historians call the USSR’s “suicide” had long been apparent. The USSR had attempted to create a “’modern’ society, defined as one characterized by industrialization, secularization, urbanization and rationalization,” while at the same positioning itself as the alternative to liberal Western modernity. Despite its “permanently revisionist stance in international affairs,” the state had become moribund. The revolution was over: “in practice the Soviet Union became in effect a status quo power,” as complicit in upholding the global state of affairs as the U.S.

A woman reaches into her bag, which rests on a fallen Soviet hammer-and-sickle on a Moscow street in 1991

A pro-democracy demonstrator fights with a Soviet soldier on top of a tank parked in front of the Russian Federation building on August 19, 1991, after a coup toppled Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev.

The actual practice of glasnost, rather than its invocation as an ideal, accelerated a total collapse of confidence in Soviet communism among the Soviet people, who could now read about the horrific abuses of past and present regimes and “who were no longer willing to endure sacrifices to support Soviet ‘internationalist’ ambitions abroad.” Gorbachev might have saved the Communist Party, and the Soviet State—or at least enabled them to limp on a while longer—had he been willing to use the repressive means at his disposal. The example of present-day China, Sakwa offers, is historically instructive.

The absence of sustained coercion in part derived from Gorbachev’s fundamental refusal to operate within the framework of Petr Stolypin’s well-known injunction that ‘in Russia liberal reforms can only be possible if the regime first clamps down, because for a Russian any relaxation in the system represents weakness.’ This, however, is an injunction which Vladimir Putin appears to have taken to heart.

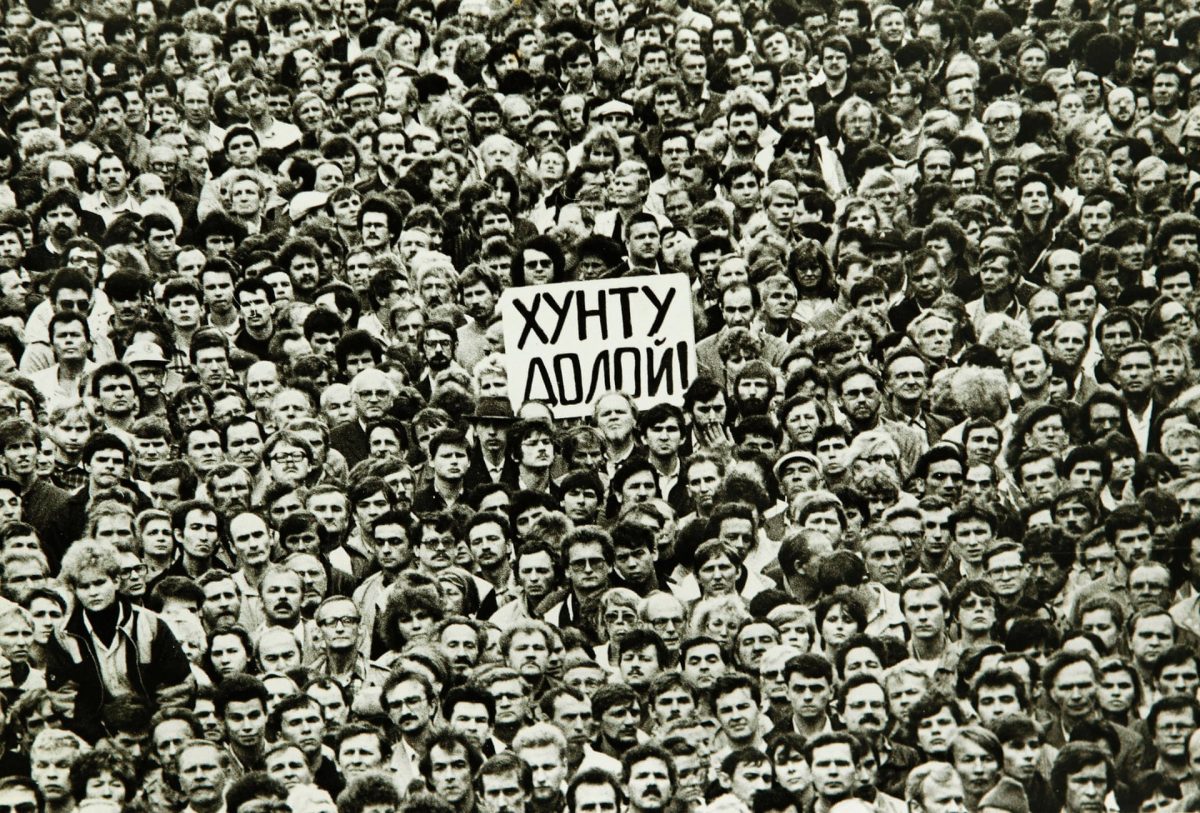

Still, it was clear, at the end, that the ideological supports for the system had crumbled, and not even the failed coup of August, 1991 could prop them up again, as Soviet citizens turned on the army and urged soldiers to abandon efforts to turn back the clock. As for all that has happened since, the nostalgia many Russians feel for the Soviet regime speaks not only to the rosy view all people tend to adopt when looking backward, but also to a sense that something deeply important to them was lost in 1991.

It’s also notable that Gorbachev is viewed quite favorably in former Soviet republics and formerly Communist countries in Central Europe. His “tragic success” broke the spine of an empire that starved, repressed, jailed, and displaced millions; it also helped assure that massive corruption and authoritarianism would continue to rule Russia three decades after the USSR’s dissolution.

via The Guardian

Part of a large crowd, outside the Russian Parliament building in Moscow, celebrates the news that the hardline Communist coup has failed, on August 22, 1991

Citizens of the Ukraine vote on a referendum for independence from the Soviet Union at the Ukraine Embassy in Moscow, on December 1, 1991

Vilnius, Lithuania – September 1, 1991

A Baku resident uses an axe to hack apart a placard showing a portrait of Russian Bolshevik revolutionary leader Vladimir Lenin, on September 21, 1991. Azerbaijan was proclaimed a Soviet Socialist Republic by Soviet Union in 1920. The Azeri National Council voted for its declaration of independence in 1991.

For one of the last times, the Soviet flag flies over the Kremlin at Red Square in Moscow, on Saturday night, December 21, 1991. The flag was replaced by the Russian flag on New Year’s

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.