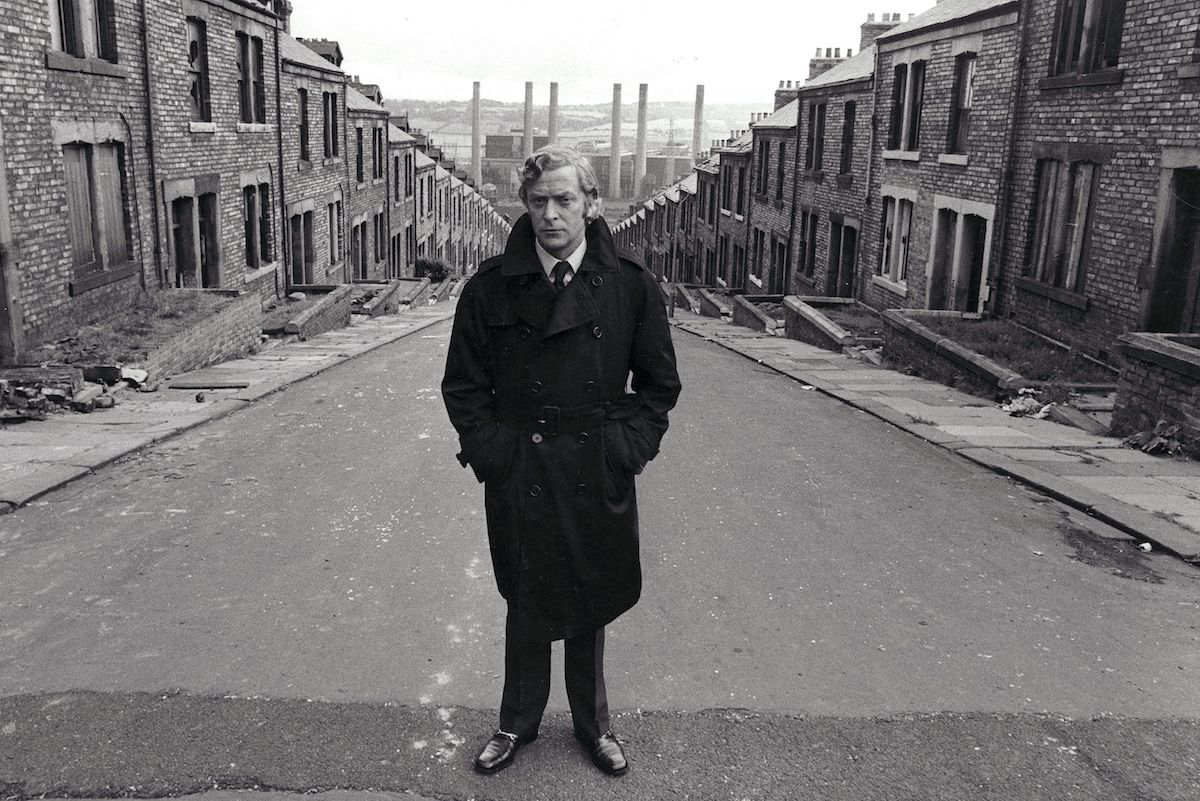

July 1970: Michael Caine & Ted Lewis on Frank Street in Benwell (now demolished) with the Dunston B Power Station in the distance (demolished in 1986).

Early in Ted Lewis’s novel Jack’s Return Home, published in 1970 and which was made into the film Get Carter the following year, Jack arrives at 48 Jackson Street – his dead brother’s house in Scunthorpe (un-named). It had once been Jack’s childhood home but inside it was all but unrecognisable. The wallpaper was ‘all light browns and pale greens’, the bannisters had been ‘hardboarded in’ and the light fitting above the stairs ‘was triple-stalked in some fake brassy material’. In the room described as the scullery there were ‘tongue and groove units’ each side of the chimney breast – on one side there was a neatly boxed in television with a little section for the TV Times and Radio Times, and on the other there were Jack’s brother’s paperback books and records.

Amongst the Stan Kenton, Mel Tormé and Frankie Laine LPs was the 1960 PYE recording This is Hancock. It was actually Tony Hancock who may have inspired the name of the original novel. On the album Pieces of Hancock, also released in 1960, there is a spoof melodrama entitled ‘Jack’s Return Home’ part of the East Cheam Drama Festival originally broadcast in 1958. Nick Triplow in Getting Carter: Ted Lewis and the Birth of Brit Noir suggests that the original title of Ted Lewis’s book could have been a small tribute to Hancock who had committed suicide in June 1968, not long before Lewis had started writing it.

Pan Books film tie-in paperback of Ted Lewis’s novel Jack’s Return Home – the movie at that stage was to be called just Carter.

The novel garnered the odd good review notably by Graham Lord in the Sunday Express where he described the book as ‘fast, earthy and violent, but also extremely well written’ and added that the cinematic style made ‘compulsive reading’. The Sunday Times joined in with the praise and said that ‘Ted Lewis can write tersely and well’. Although it was hardly a best-seller ‘Jack’s Return Home’ was not unnoticed in the US where the New York Times wrote: “The style is side-of-the-mouth American crime novel, but the milieu is the minor league British underworld: provincial gambling halls, sleazy pubs, blue movies. There is even a glossary of English cant – nice to know but hardly necessary. The words are exotic but the melody is familiar.” American Publishers Weekly also praised the book arguing the book ‘introduces us to a vivid parade of wildly vulgar and foul-mouthed people’.

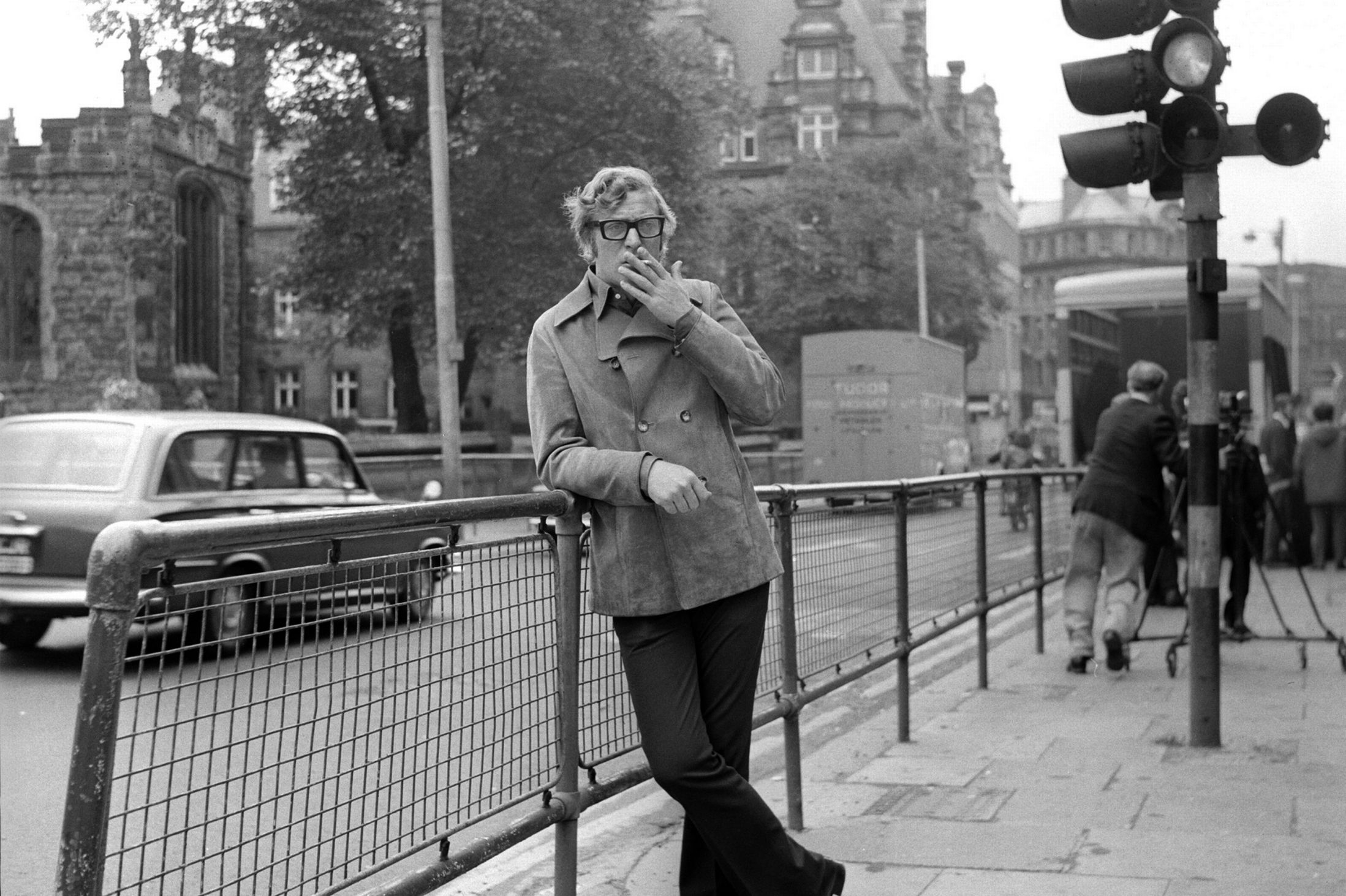

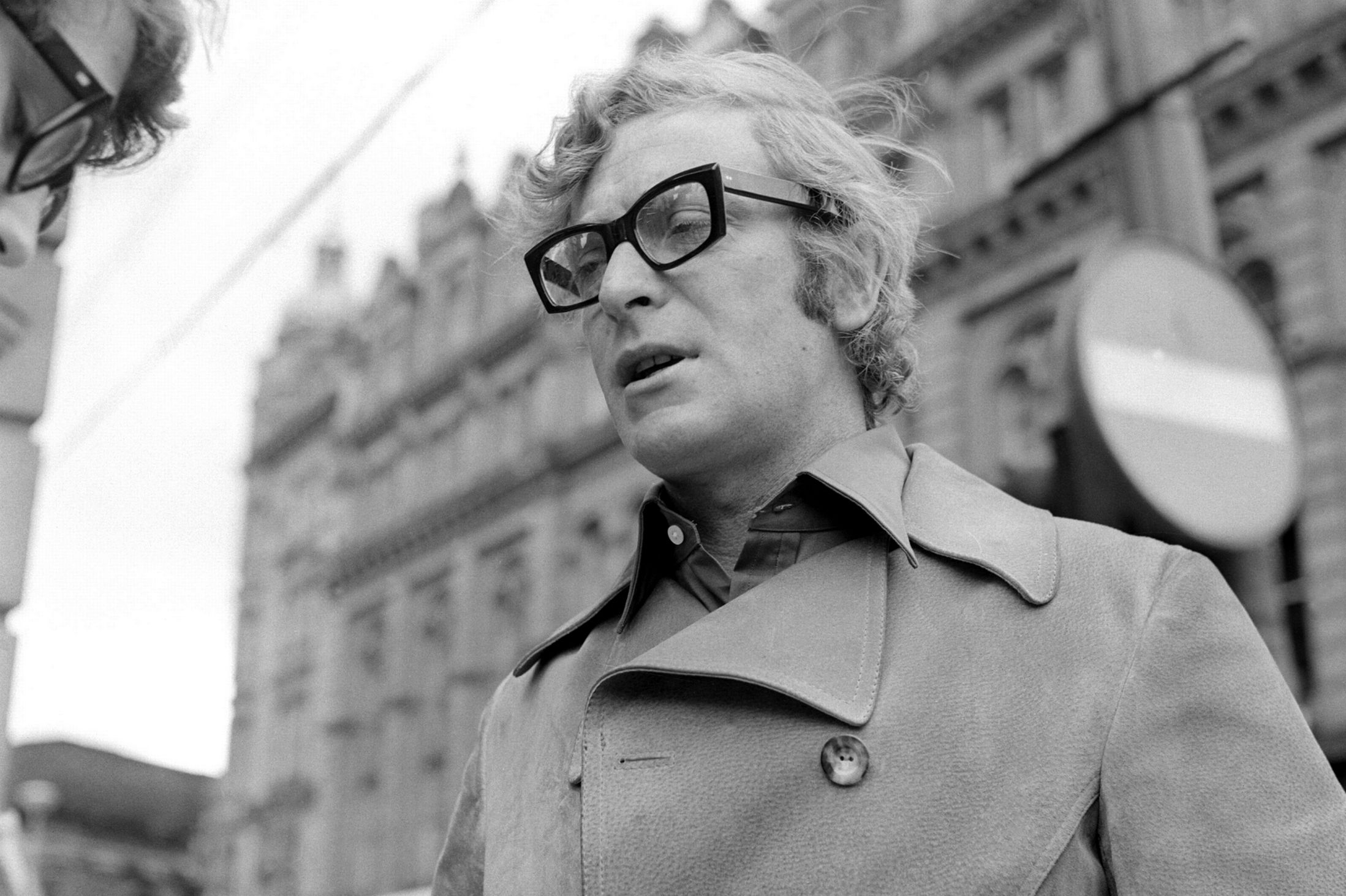

English actor Michael Caine stops for a chat during the filming of Mike Hodges’ gangster classic ‘Get Carter’, circa 1971. In the background, on the left, is playwright John Osborne, who also stars in the film. (Photo by Terry O’Neill/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Ted Lewis was born in Manchester in 1940 but his family moved to the Lincolnshire town of Barton-on-Humber two years after the Second World War. After school Lewis spent four years at Hull Art School where his experiences became his autobiographical first book, published in 1965, All the Way Home and All the Night Through. After art college, and not an untalented artist, Lewis became an animator. In the summer of 1967 he joined the production team working on the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine. It was a chaotic production and hard-work but at 2.00pm on Monday, 8 July 1968, and nine days before the world premiere, three of the Beatles arrived at a press-screening of the eagerly awaited animated movie. It was at the 102-seat cinema situated inside Bowater House in Knightsbridge, a massive post-war office block that was distinctly ‘carbuncular’ in appearance. It had been built a decade before in 1958 by the developer Harold Samuel for the Bowater-Scott Corporation the world’s largest newsprint company, and the building completely dominated the adjacent Scotch Corner junction. It had been a hot week and the screening cinema was chosen as one of the few in London to feature air-conditioning.

John Lennon was the Beatle missing at the film-screening, and he was almost certainly at home completely stoned, although Paul, George and Ringo jokingly posed for the photographers with a life-size cardboard cutout of John’s cartoon character. Harrison told reporters that because of the bad reviews of the Magical Mystery Tour the previous year, the Beatles from now on would only appear in animated form. He then tried to avoid answering a question about the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi but McCartney interrupted and said that the episode was just ‘a phase’ and that ‘we don’t go out with him anymore’.

After working as an animator and designer on a BBC children’s show called Zokko! (it seems odd now but the series was the first ever BBC TV show to air on a Saturday morning) Lewis started the first draft of his second novel. Early in 1970 Jack’s Return Home was eventually published by Michael Joseph who had paid the author a £6000 advance for the privilege.

Graham Lord was not alone to notice the ‘cinematic style’ of the novel and the film rights were quickly bought. Directed by Mike Hodges, a man in his late-thirties who at this point had only directed for television, the film quickly went into production, initially renamed ‘Carter’ and then ‘Get Carter’. Hodges wrote the screenplay himself, admitting later that he was initially inhibited by following the novel too closely, but the changes were all approved by Ted who made sure he was present at most of the filming. Hodges would later write in a forward of a later publication of the novel:

It arrived in the post, out of the blue, along with an offer to write and direct it as my first cinema film. Its literary style was as enigmatic as the manner of its arrival. Whilst set in England and written by an Englishman it was (aside from the rain) atypically English. More importantly it ripped off the rose-tinted glasses through which most people saw our mutual homeland. I suspect Ted never shared that Panglossian take on England.

Get Carter is now pretty well seen as a stone-cold British classic but although it was more popular than it’s parent novel the reviews were still mixed. The Guardian described it as a: ‘cold, sour film with scarcely a sympathetic character in sight.’ While Derek Malcolm, in the same newspaper, wrote that it was ‘a curiously distasteful affair.” Nigel Andrews in the Monthly Film Bulletin was particularly dismissive:

No amount of picturesque violence (bodies splayed across car windscreens or hurtling from high buildings) can redeem Get Carter’s perfunctory plot, its mechanical manipulation of characters or a vision of the British underworld that relies totally on cliché.

In the US, however, some of the reviews were more positive. Variety wrote:

One could easily lose count of the number of the slayings, and some of them are far from implied. However, a major value in the film is the genuinely artistic way in which the gore is handled: good taste may seem a strange way of describing it, but it’s true.

Favourable some of the reviews may have been but the movie sank without trace in America with almost no distribution.

Although Ted Lewis had written the source material for Get Carter he was almost forgotten. In 1971 Barry Norman, in an interview with the director Mike Hodges, dismissed the original source material as “someone else’s novel.’ Meanwhile Lewis’s wife was interviewed in the Daily Express:

Josephine Lewis is rather worried about her husband author Ted Lewis. Not that he isn’t an ideal husband and quiet-living family man devoted to his two young daughters. But the books he writes in their country cottage at Framlingham, Suffolk, are among the most vicious and blood-thirsty on the market.

Josephine, who is 28, says, “It never ceases to amaze me that such a gentle man can create characters who are so savage and vile. I can’t stop myself watching his every move to assure myself he isn’t adopting any of this characters’ faults.

Lewis published seven more novels including two that featured Jack Carter. He also scripted a few Z-Cars episodes. Lewis always enjoyed a drink a little too much and by the year his final novel GBH was published in 1980 he was an alcoholic. By now he had separated from his wife and family and was now living in Scunthorpe with his mother. Two years later, in 1982, he died of an alcohol-related illness. He was just forty-two.

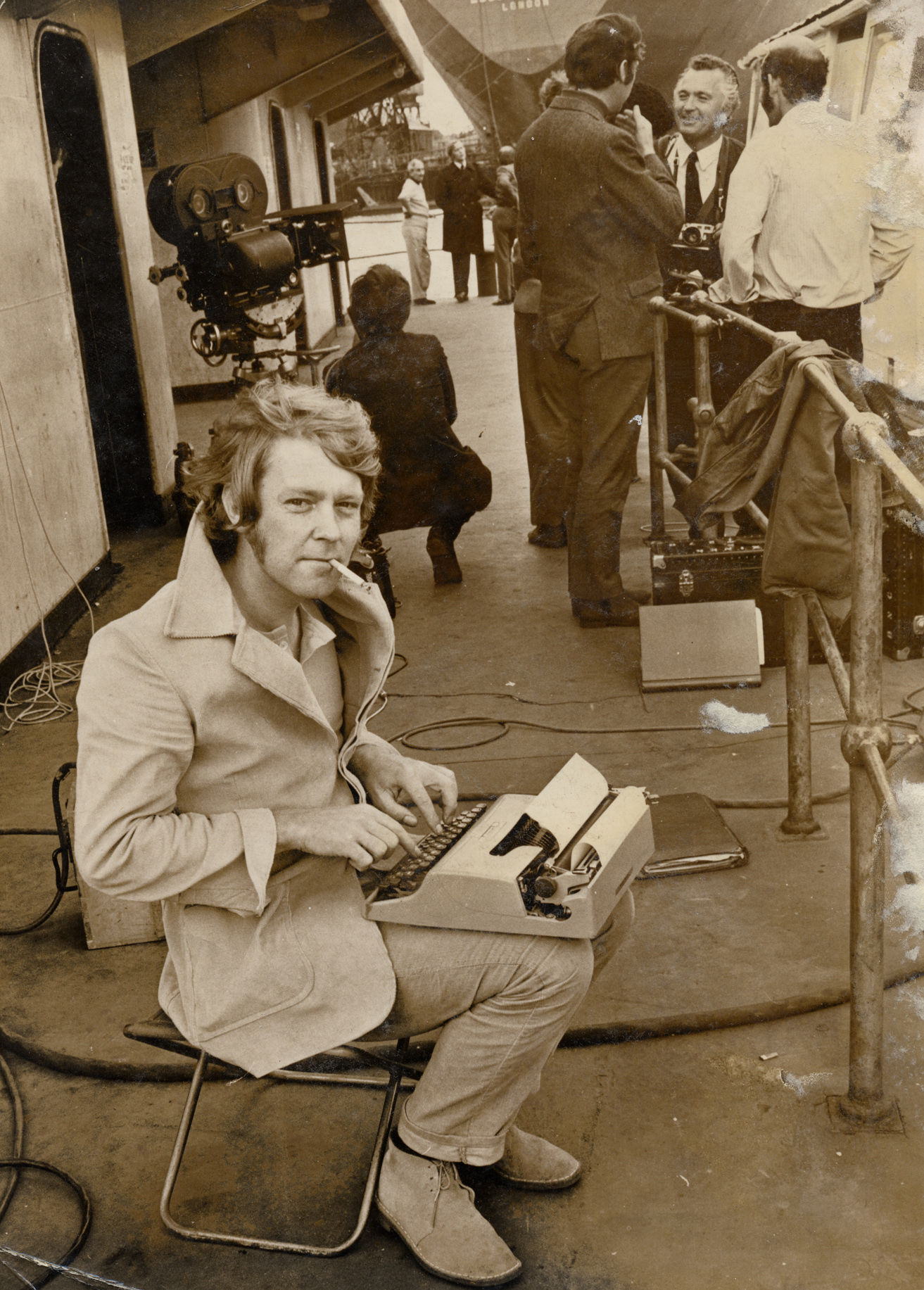

Ted Lewis – appeared in Scunthorpe Evening Telegraph dated Thursday, January 31, 1980 – story by Nick Cole. Pic taken Monday, January 28, 1980.

If you would like to read more about Ted Lewis and his novels and the film Get Carter buy Nick Triplow’s brilliant book Getting Carter: Ted Lewis and the Birth of Brit Noir

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.