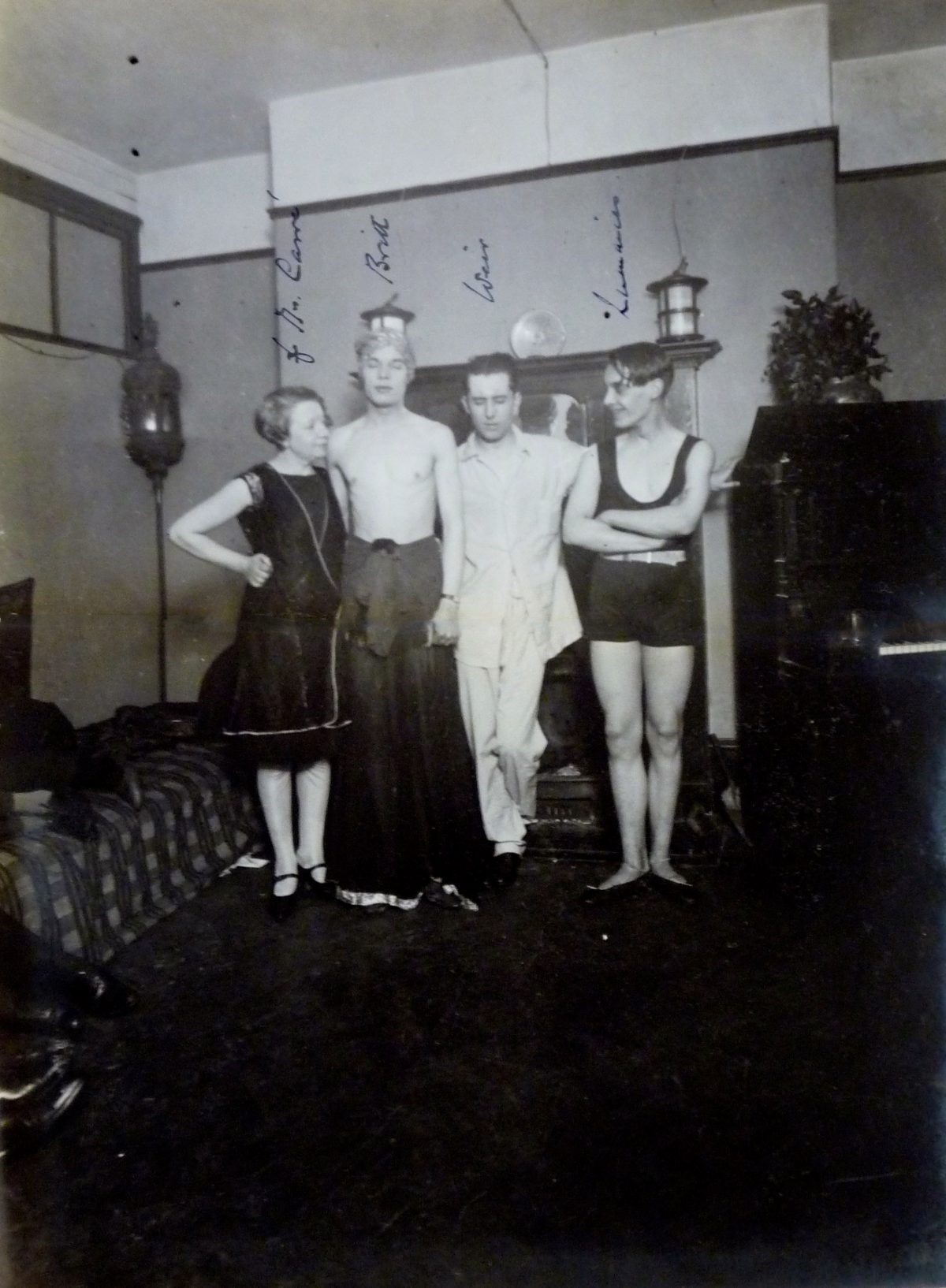

At one in the morning on 16 January 1927, Superintendent George Collins of the Metropolitan Police knocked on the door of the basement flat at 25 Fitzroy Square. A woman called Constance Carre answered and after being told they had a warrant to arrest the occupants, she responded: ‘But Mr Britt was going to give us a Salome dance!’

The superintendent and his fellow officers barged past her and quickly entered the flat. They came across a twenty-six-year-old man who was wearing, as a police report would later describe, ‘a thin black transparent skirt, with gilt trimming round the edge and a red sash … tied round his loins’. The same report added that ‘he wore ladys [sic] shoes and was naked from the loins upwards’.

The oddly attired man gave his name as Robert Britt and said:

I am employed in the chorus of ‘Lady Be Good!’. These are a few friends of mine. I was going to give an exhibition dance when you came in. I have been here for about eight months and pay two pounds five shillings weekly for the flat. Carre is my housekeeper. I was a Valet to a gentleman for about nine years who died last November. I did not like that sort of life, so as I’m considered good at fancy dancing I decided to go on stage … Some of the men I have known for a long time and they bring along any of their friends if they care to do so.

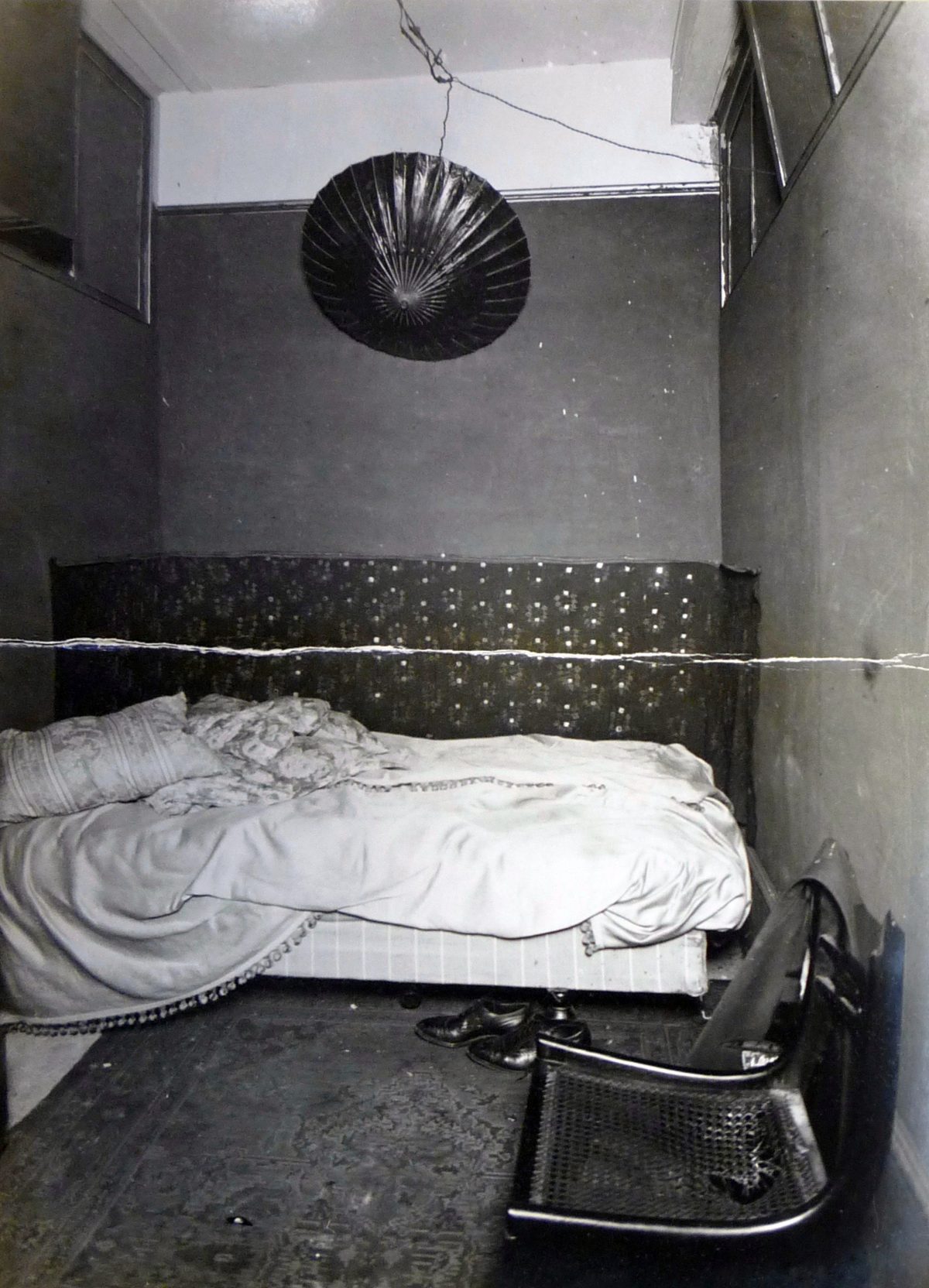

It would eventually come to light that the police had been staking out Britt’s flat for a month or so. Sergeant Spencer and Police Constable Gavin of D-Division had spent 16 and 17 December 1926 and 1 and 2 January 1927 essentially peering into the front and rear of the property noting any nefarious activities that were supposedly taking place. Police Sergeant Arthur Spencer wrote: ‘At 11.45 p.m. I saw two men, who I saw enter at 11.30 p.m., leave, they were undoubtedly men of the Nancy type. They walked cuddling one another to Tottenham Court Road, where they stood waiting for a bus. I stood close to them and saw their faces were powdered and painted and their appearance and manner strongly suggested them to be importuners of men.’ Police Constable Gavin also contributed to the report: ‘I saw from the roof into a bedroom in the basement, where two men entered the bedroom; they both undressed and got into bed and the light was put out. I heard them laugh and scream in very effeminate voices.’

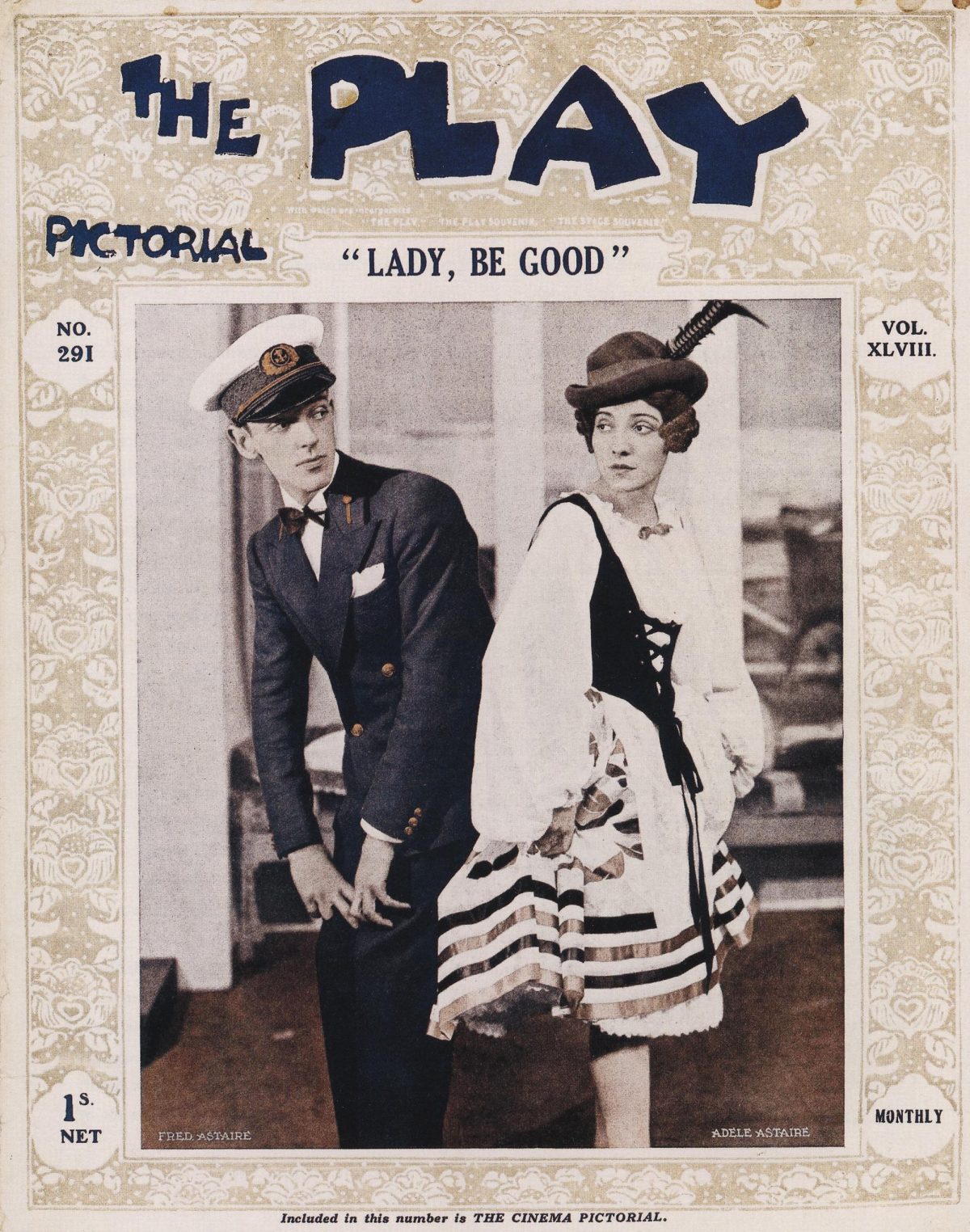

Londoner Bobby Britt, the youngest of four children, had been born in Camberwell at the turn of the century. As he mentioned to the police when they raided the flat, he was performing at the Empire Theatre in the dancing chorus of Lady Be Good! – the Gershwin brothers’ first Broadway musical and which starred the brother-and-sister team of Fred and Adele Astaire.

The musical had been a huge success in New York and on 14 April 1926, to perhaps even greater acclaim, Lady Be Good! opened at the Empire Theatre on Leicester Square. At the time of his arrest Bobby Britt was dancing in easily the hottest show in town.

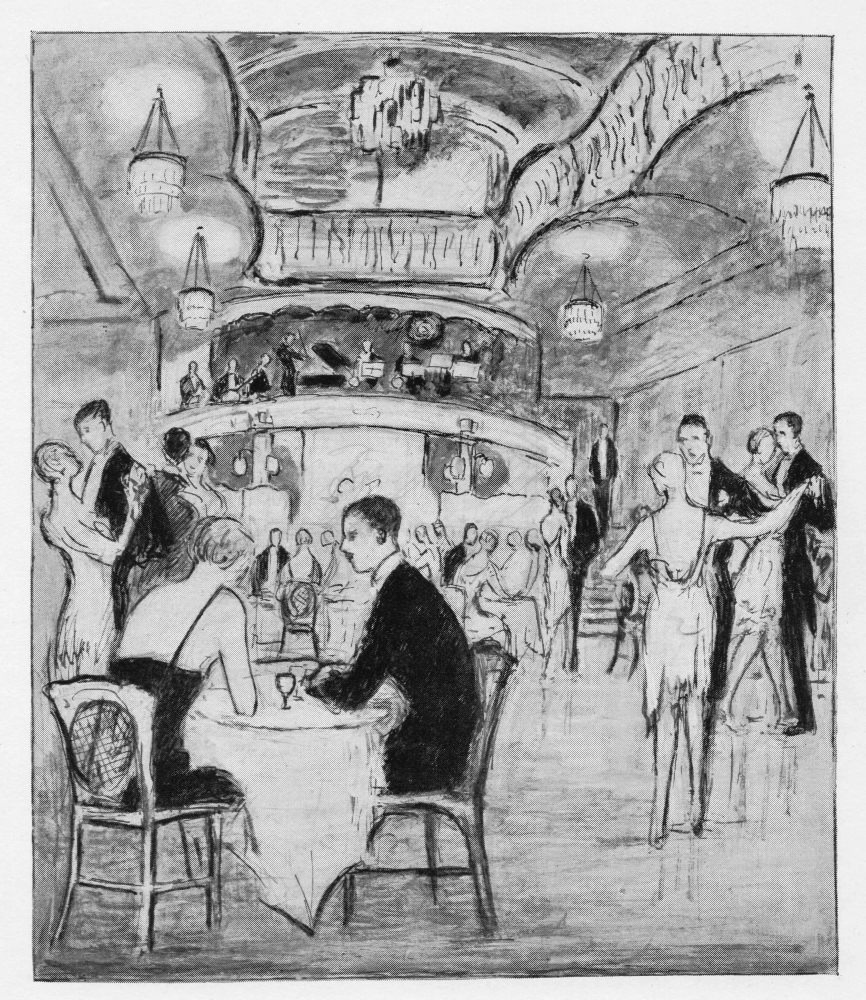

George Gershwin himself attended the opening night and huge crowds came to the theatre, just to stand outside. Later, accompanied by the Astaires, the composer partied at the fashionable Embassy Club on Old Bond Street, where he stayed until eight in the morning. The Embassy had opened in 1919 and after the Prince of Wales had become a regular (a couch was reserved specifically for his use) it had soon become the fashionable place to go . The music for the first-night party was provided by Ambrose and his Orchestra, who were back playing regularly at the nightclub after a lucrative period performing in New York. They had been persuaded back to London by a telegram from the Prince of Wales himself: ‘The Embassy needs you. Come back – Edward.’

The reviews for Lady Be Good! were on the whole good, especially as far as Fred and Adele were concerned. The Times enthusiastically wrote of them: ‘Columbus may have danced with joy at discovering America, but how he would have cavorted had he also discovered Fred and Adele Astaire!’

The Daily Mail thought Lady Be Good!, was ‘a particularly fine brand of musical comedy’, and singled out the sister: ‘Miss Adele Astaire is the live wire of the piece. She dances so well, she sings in a way to give point to some ordinary lyrics, she shows a true sense of comedy, she laughs and romps her way into everyone’s favour.’ The Astaires had been a successful vaudeville act since 1905, and in 1926, when they both travelled to London to appear in Lady Be Good!, Adele was actually the bigger star of the two – Fred at this stage of his career played almost a supporting role. Professionally, the siblings were completely different; Fred, a constant worrier, was never happy with his or his sister’s performance and usually arrived at the theatre two hours early to limber up and practise, while Adele, a much more relaxed individual, would generally turn up a few minutes before she was due on stage.

Adele enjoyed her new-found celebrity status on both sides of the Atlantic, and particularly appreciated the attention she had started to get from wealthy young aristocrats. In 1932 she retired from the stage and her professional relationship with her brother when she married Lord Charles Arthur Francis Cavendish and moved to Ireland, where they lived at Lismore Castle. She had been dancing most of her life, but Adele made no attempt to hide the fact that the theatrical life wasn’t really for her: ‘It was an acquired taste,’ she said, ‘like olives.’

Thirty years before Fred and Adele danced on the stage of the Empire to such acclaim, Oscar Wilde had his character Algernon Moncrieff mention the theatre in the first act of The Importance of Being Ernest:

Algernon. What shall we do after dinner? Go to a theatre? Jack. Oh no! I loathe listening.

Algernon. Well, let us go to the Club?

Jack. Oh, no! I hate talking

Algernon. Well, we might trot round to the Empire at ten? Jack. Oh, no! I can’t bear looking at things. It is so silly.

Oscar Wilde, who wrote his last and ultimately most successful play during August 1896 (fourteen years after the Empire Theatre had opened), knew the connotations most of the audience would glean from ‘the Empire’ reference. While Wilde had been writing the play, the Empire had been in the news for months due to the ‘purity campaign’ ran by the indomitable vice-campaigner Mrs Ormiston Chant. The Daily Telegraph in particular gave it huge coverage, worried about ‘the prudes on the prowl’. Laura Ormiston Chant had been persuaded to visit the Empire Theatre of Varieties after two of her American friends had had a particularly bad experience there while visiting in the hope of seeing coster songs sung by Albert Chevalier. They missed Chevalier but complained to Mrs Chant of ‘the character and the want of clothing in the ballet’ and, on the second-tier promenade, of being ‘continually accosted at night and solicited by women’.

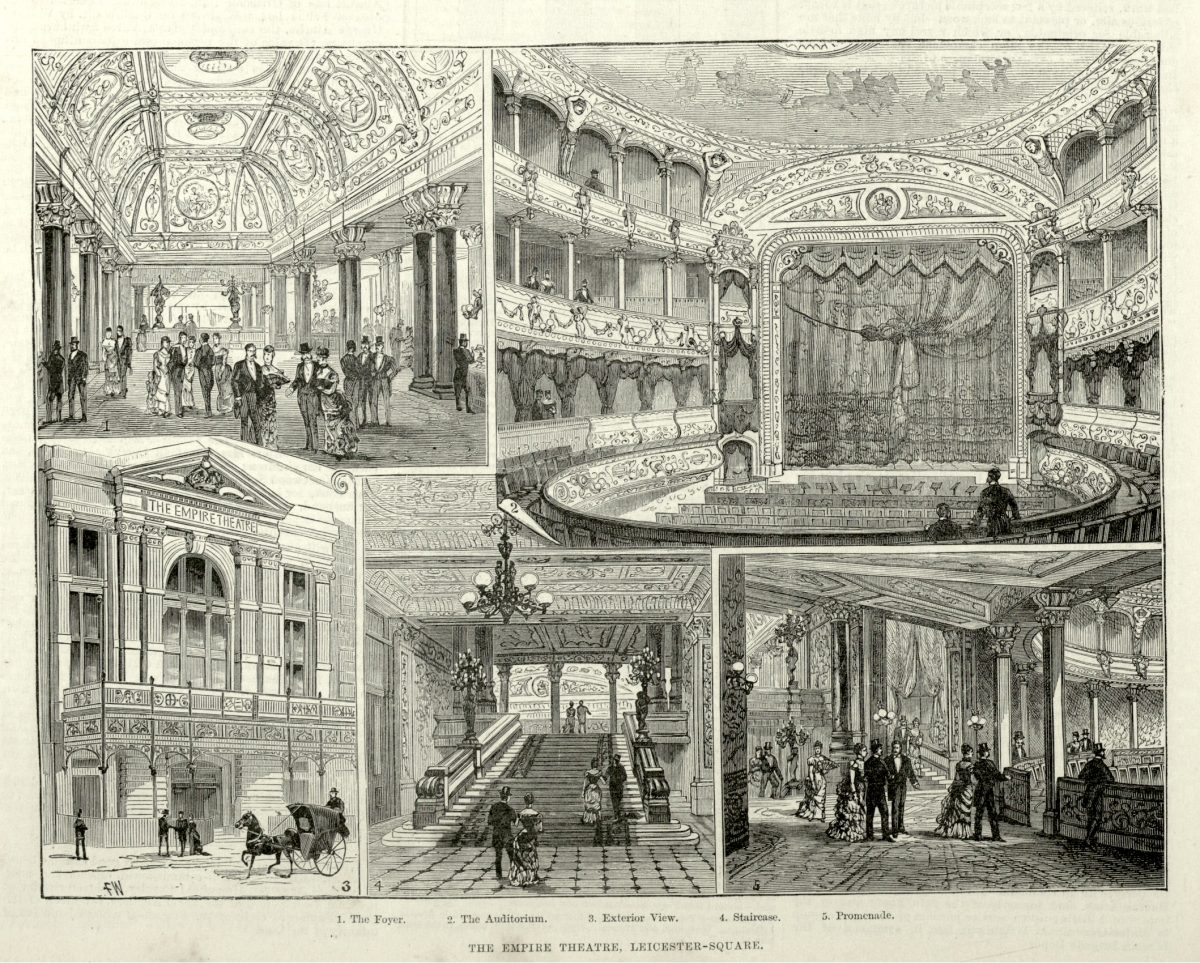

Prostitution and the theatre had, of course, always been pretty close bedfellows, so to speak. At Wilton’s music hall, for instance, it was flagrant: the gallery could only be entered through the brothel inside which the hall had been built. In the 1890s the Empire in Leicester Square was justly famous as a variety and musical hall theatre but in reality, the dominant attraction, and what Wilde was almost certainly referring to, was the Empire’s second-tier promenade. This was an area behind the dress circle where you could still see the stage if you wanted to, but which was essentially a place to pick up high-class prostitutes.

The theatre charged half a crown for a rover ticket that allowed you to wander around, but there were also comfortable seats and what was called an American bar serving one-shilling cocktails such as the Bosom Caresser and the Corpse Reviver. It was known to many as ‘The Cosmopolitan Club of the World’, and the essayist and caricaturist Max Beerbohm described it as ‘the reputed hub of all the wild gaiety in London – that Nirvana where gilded youth and painted beauty meet … in a glare of electric light’.

Enchanted Mrs Chant was not, and she was of the opinion that it was the risqué ‘abbreviated costumes’ on stage that encouraged and contributed to the indecent and indecorous air of the promenade. The women she observed who were ‘very much painted’ and ‘gorgeously dressed’ didn’t sit down but walked about the promenade on the lookout for men. When the theatre was darkened for the ‘living pictures’ their behaviour was ‘very objectionable indeed’. Mrs Chant eventually told the London County Council, who were responsible for the licensing of the Empire: ‘We have no right to sanction on the stage that which if it were done in the street would compel a policeman to lock the offender up … The whole question would be solved if men, and not women, were at stake. Men would refuse to exhibit their bodies nightly in this way.’

Mrs Chant’s efforts were not in vain, and she managed to persuade the LCC in October 1894 to instruct the Empire to build a barrier between the theatre itself and its infamous ‘haunt of vice’ promenade. Although, when the Empire Theatre management put up canvas screens to hide the auditorium from the promenade, a rioting audience quickly tore them down. The crowd was egged on by the young Sandhurst cadet Winston Churchill, who shouted: ‘Ladies of the Empire, I stand for Liberty!’ Churchill later wrote about what he had said that night: ‘“You have seen us tear down these barricades tonight; see that you pull down those who are responsible for them at the coming election.” These words were received with rapturous applause, and we all sallied out into the Square brandishing fragments of wood and canvas as trophies or symbols. It reminded me of the death of Julius Caesar.’ Four days after the incident, Churchill wrote to his brother: ‘Did you see the papers about the riot at the Empire last Saturday? It was I who led the rioters – and made a speech to the crowd.’

Mrs Ormiston Chant would have been even more shocked and horrifed had she known what was going on within the less prestigious and cheaper rst-tier promenade. Oscar Wilde, however, almost certainly did know, and his ‘Empire’ reference almost certainly had other connotations to a more select part of his play’s audience. At the cheaper price of only one shilling, the Empire Theatre’s first-tier promenade was said to be the gay pick-up location in the whole of London. A letter to the council dated 15 October 1894, just six weeks after Mrs Chant’s visit to the theatre, described the rough ejection of a man from the shilling promenade by Robert Ahern, the front-of-house manager. The letter writer described the man who was thrown out as a ‘‘sodomite’, as were perhaps half the occupants of that promenade, that it was the only venue for people of this kind, and that he ‘could lay his hands on 200 sods every night in the week if he liked’.

It’s not known whether Oscar Wilde ever went to ‘look at things’ in the first-tier promenade at the Empire Theatre but at that time it was exactly the kind of place he would have frequented. Just a few months after Mrs Ormiston Chant’s intervention at the Empire Theatre, and only two months after The Importance of Being Ernest premiered at the St James’ Theatre in February 1895, Wilde was charged with gross indecency after a failed libel case with the belligerent little Marquess of Queensbury. Wilde was convicted under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, and sentenced to two years’ hard labour. The judge, Mr Justice Wills, described the sentence, the maximum allowed at the time, as ‘totally inadequate for a case such as this’. Wilde’s response was ‘And I? May I say nothing, my Lord?’ but it was drowned out in cries of ‘Shame’ in the courtroom. Five years later, utterly broken, he was dead.

Lady Be Good! finished its long run at the Empire, on 22 January 1927. Bobby Britt was no longer in the chorus because exactly two weeks previously he had been formally charged with keeping a disorderly house. Or, to put it in slightly more legal detail, he was charged with permitting:

divers immoral lewd, and evil disposed persons, tippling whoring, using obscene language, indecently exposing their private naked parts, and behaving in a lewd, obscene and disorderly and riotous manner to the manifest corruption of the morals of His Majesty’s Liege Subjects, the evil example of others in the like case, offending and against the Peace of Our Lord the King, his Crown and Dignity.

After some legal arguments about exactly what a disorderly house actually meant, poor Bobby Britt was sentenced to fteen months’ hard labour for essentially being a ‘nancy boy’ and enjoying the occasional party. Four of his friends were sentenced to six months without hard labour. When Bobby was eventually released in 1928, let us assume that three years later he went out to see Oscar Wilde’s Salome, perhaps to compare dances. The play, forty years after it was written – it had been banned by the Lord Chamberlain on the basis that it was illegal to depict Biblical characters on stage – had its frst public performance at the Savoy Theatre in 1931.

After his time in prison Bobby Britt took the stage name Robert Linden and lived with his parents on Lansdowne Road in Stockwell. After the WW2 he went to live with his sister in Amhurst Road in Hackney. Bobby went on to dance in many shows both in the West End and on Broadway in New York, working with Cecil Beaton, Frederick Ashton and Noël Coward. He danced at the initial BBC television trials at Alexander Palace, and he performed for the royal family at Windsor Castle. Britt eventually moved to West Sussex and became a proficient painter in his eighties and he died at the age of 100 in the year 2000.

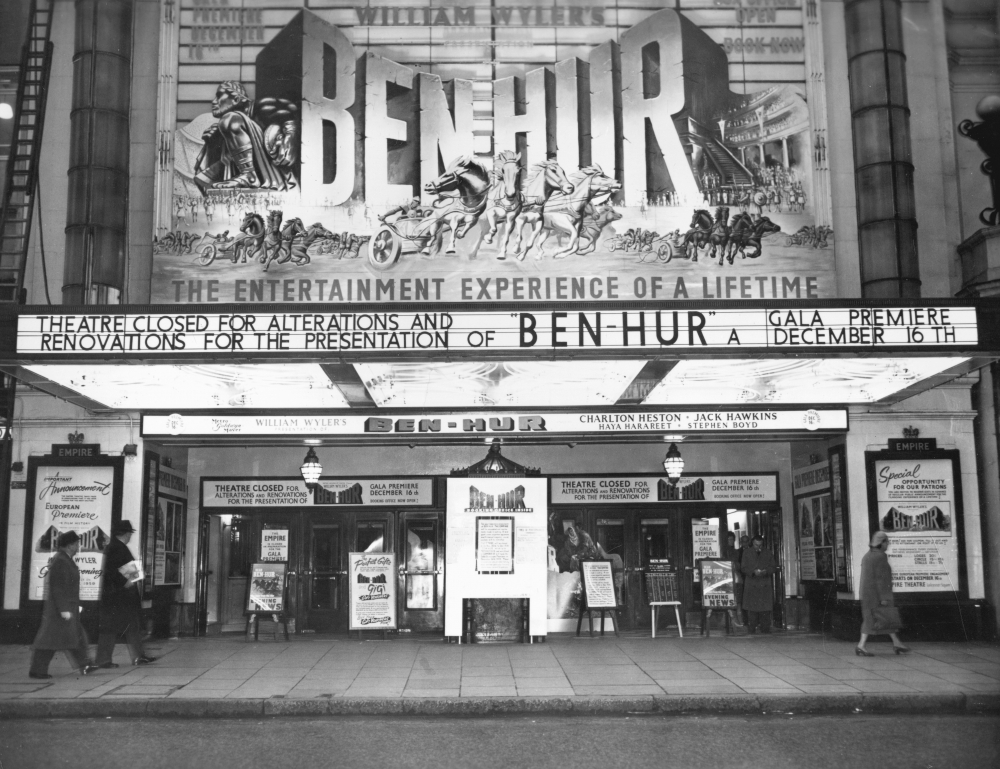

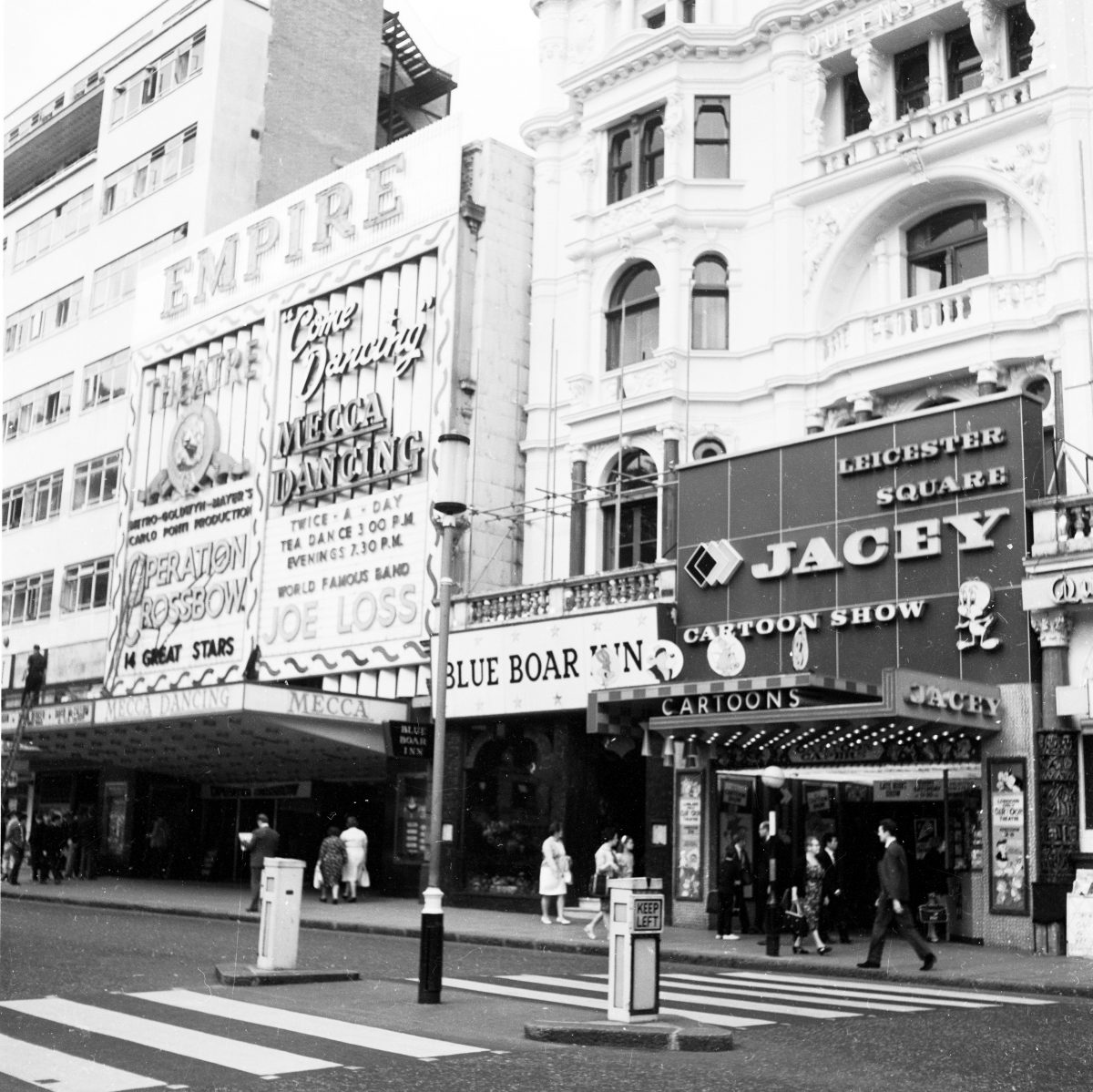

After Lady Be Good!’s run came to an end, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures, who had recently bought the Empire, promptly demolished most of the famous old theatre and built a large cinema in its place. A cinema was apt as the old Empire Theatre had been the venue, in March 1896, for the first ever commercial theatrical performances of a projected film to a British audience. The film programme, by Auguste and Louis Lumière, ran for eighteen months. The Empire Theatre cinema, in one form or another, still exists to this day.

Photograph by J Allan Cash of the Empire Theatre at Leicester Square, before the square was pedestrianised.. Image shot 1950.

This post is an excerpt from the book of London stories Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics by Rob Baker

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.