The 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire killed 146 workers, mostly immigrant women and girls trapped by fire, a collapsed fire escape, and locked doors, in a Greenwich Village garment factory. It marks a pivotal moment in 20th century history, at the nexus of concerns over labor exploitation, workplace safety, conditions of immigrant life, corruption in New York politics, and women’s emergence into the workforce.

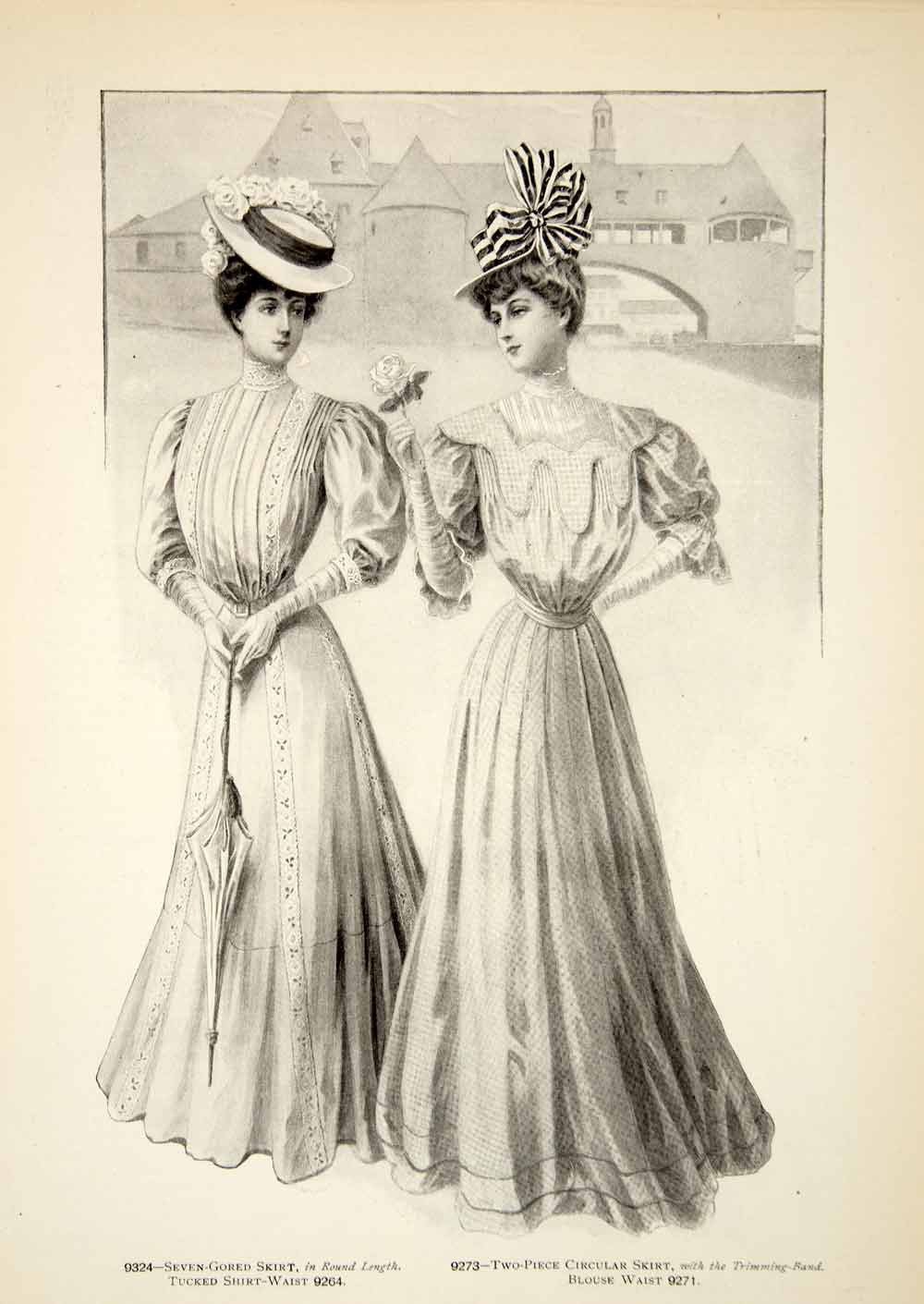

The history of the antiquated garment offers insight into a tragic irony of the fire. The shirtwaist—“a button-down blouse,” notes PBS, “originally modeled on menswear shirts”—represented far more than a fashion trend. At the turn of the century, shirtwaists came to symbolize women’s increasing economic and social independence and the progressivism associated with the suffrage movement.

With their own jobs and wages, women were no longer dependent on men and sought new privileges at home and at work. The figure of the working woman, wearing the shirtwaist blouse and free from domestic duties, was an iconic image for the women’s rights movement.

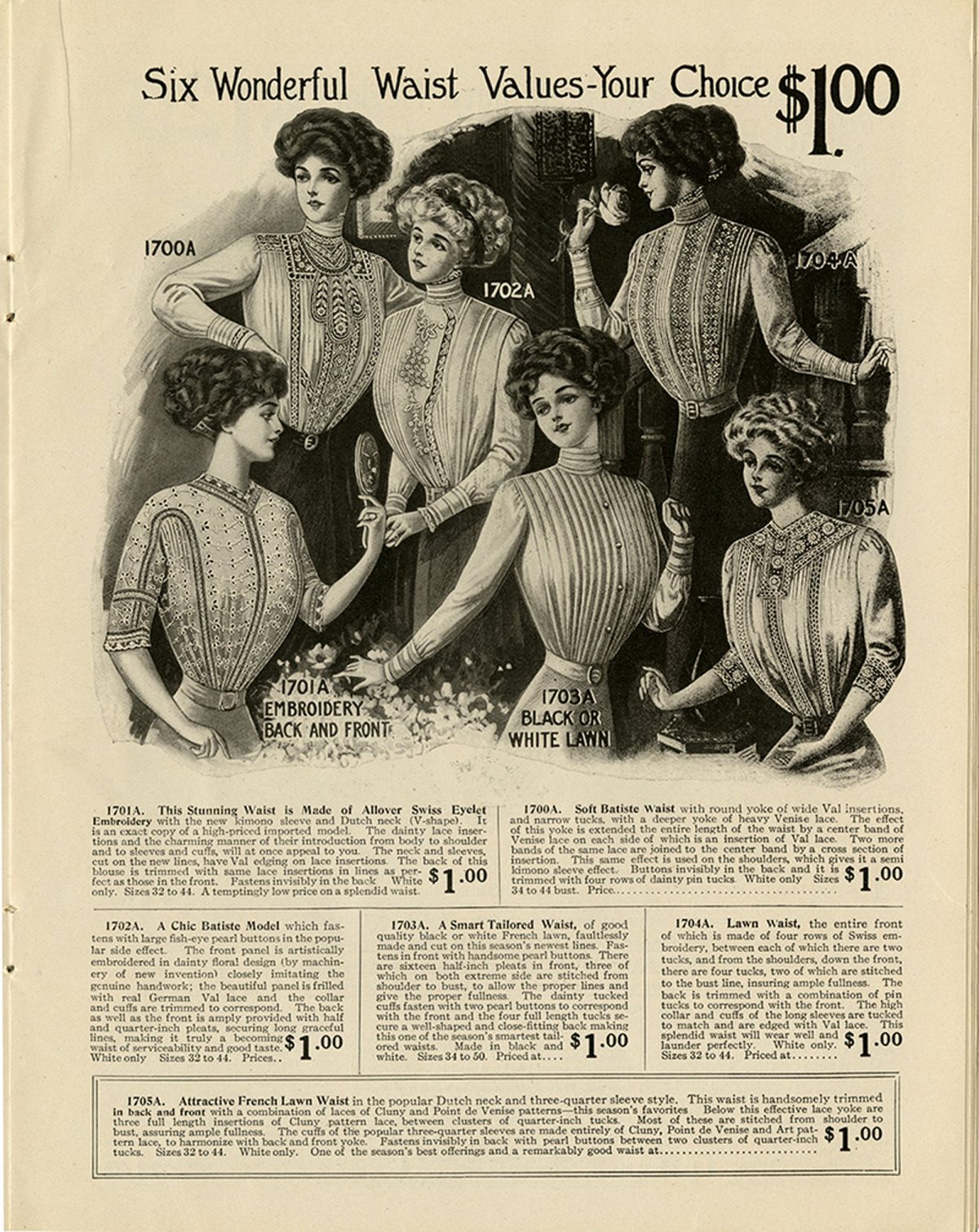

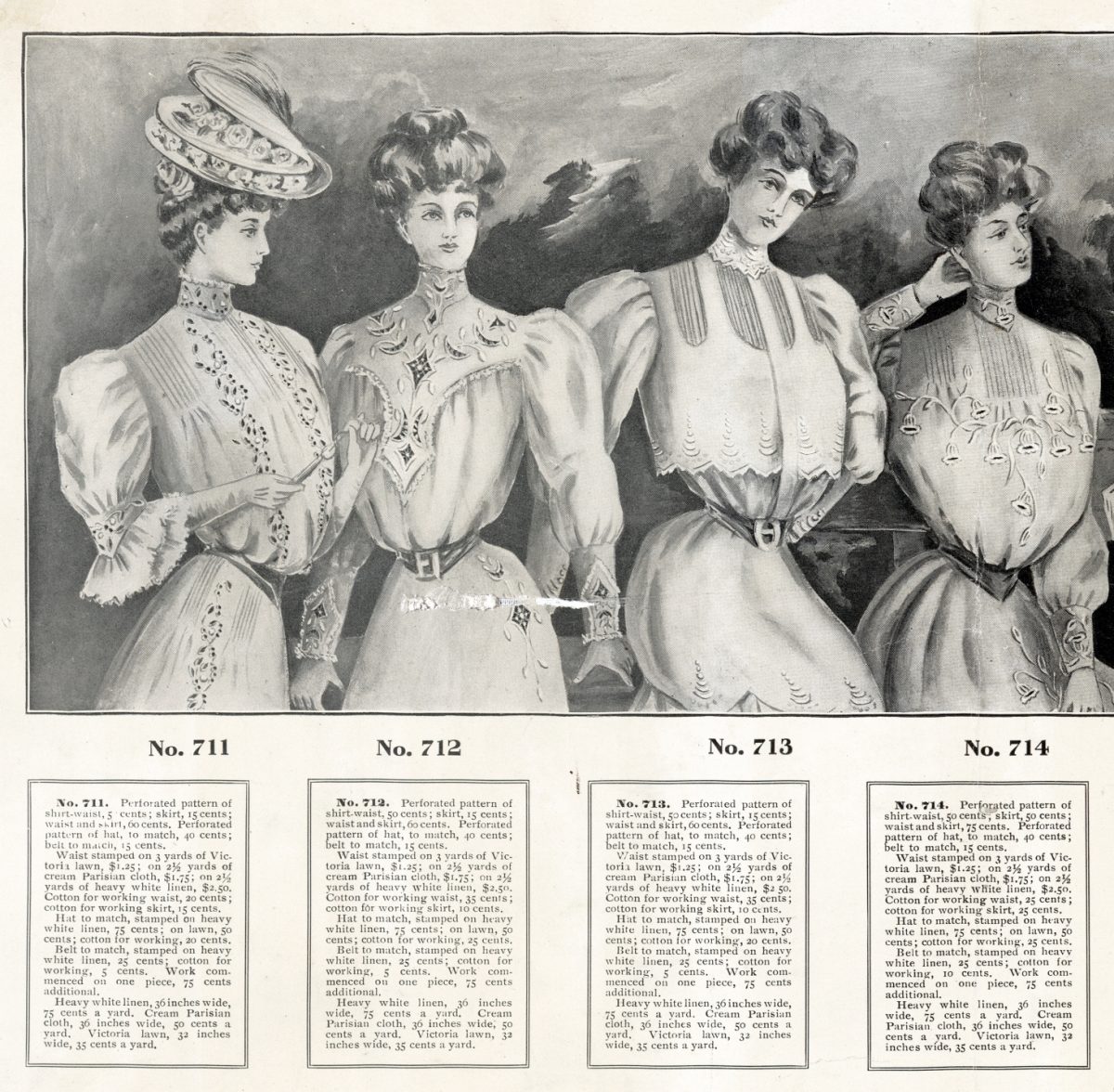

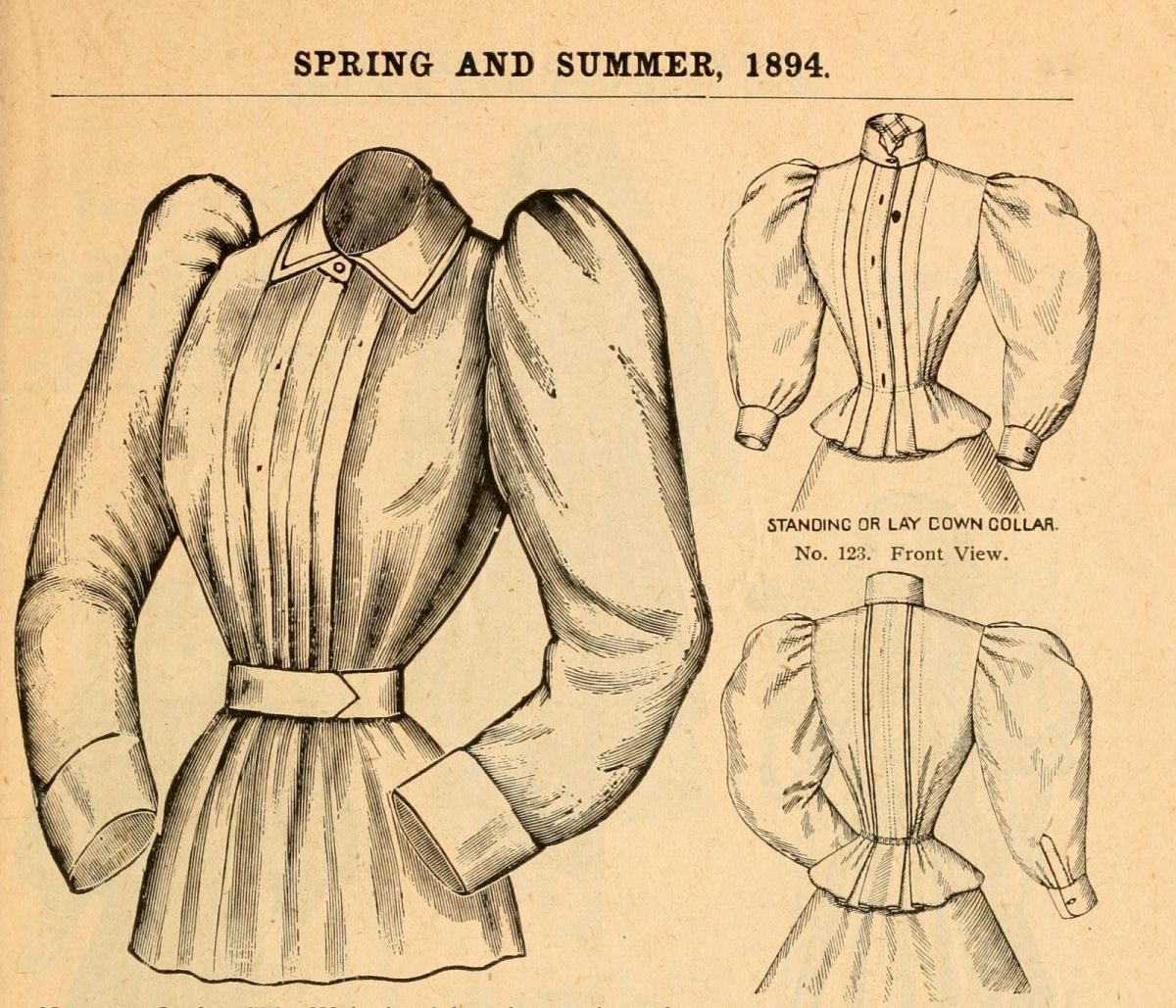

The shirtwaist, notes the Encyclopedia of Fashion, “was a liberating item of clothing. It took the place of the stiff, tight, high-collared bodices of the nineteenth century.” The garment proved so popular among hundreds of thousands of working women that its production became a hugely competitive industry. The push for sales drove the extreme “efficiency” measures responsible for the fire in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory.

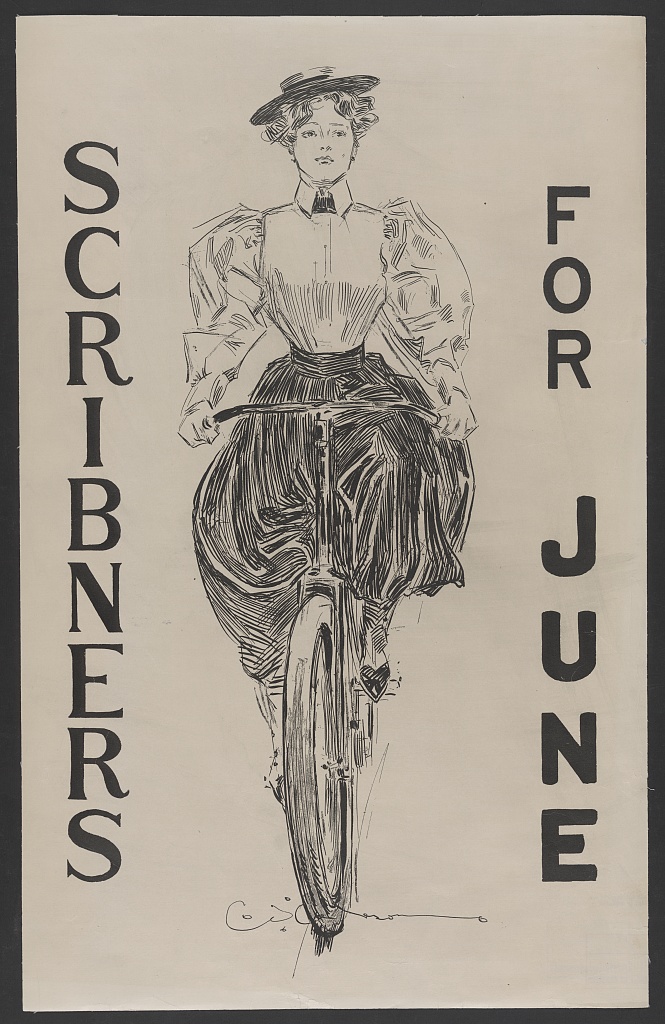

Popularization of the shirtwaist began as a middle-class phenomenon in the 1890s as “Gibson Girls,” fashionable women drawn by illustrator Charles Dana Gibson in the pages of books and magazines like Life, Scribner’s, and Collier’s, took off. Modeled on Gibson’s wife, Irene Langhorne, and her sister Nancy Astor, upper class Virginians, the Gibson Girl was a ubiquitous representation of the “new woman.” (Nancy became the first woman to serve as an MP in the British House of Commons.)

Gibson’s illustrations inspired dozens of imitators in the marketing of women’s fashions. As useful as the shirtwaist may have been in freeing women to bike, hike, and work in garment factories, its spread as a symbol of liberation had a great deal to do with advertising, the selling of new forms of individual agency that also concealed new forms of greed, as Women’s Wear Daily all but admitted in their reflections after the fire.

The lesson for the sewing trades to learn from the tragic fire at Washington place, New York, the terrible loss of life, seems to lie in the necessity of more discipline and less selfishness which is concealed under the guise of personal rights. We are individualists in this country, and yet there comes a time in every industry when the individual should consider and should be made to consider the rights of a community.

The tragic fire spurred politicians, journalists, and ordinary citizens to action, and led to the passage of workplace safety laws to “guard against the repetition of so terrible a holocaust.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.