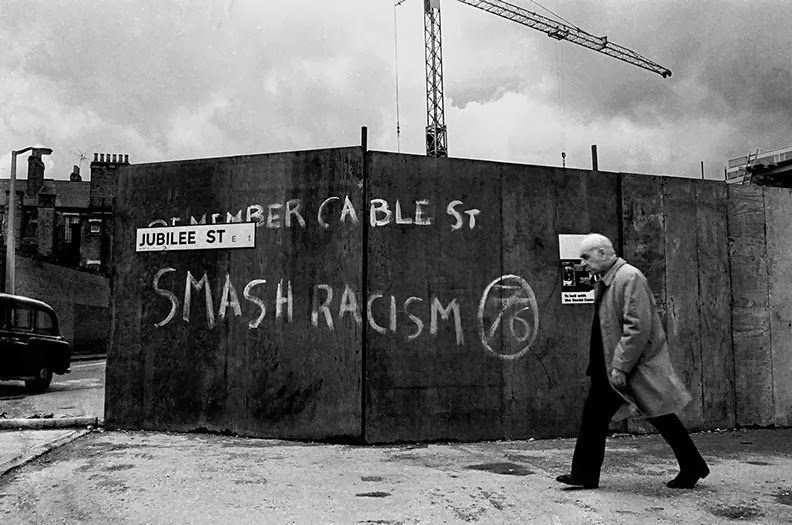

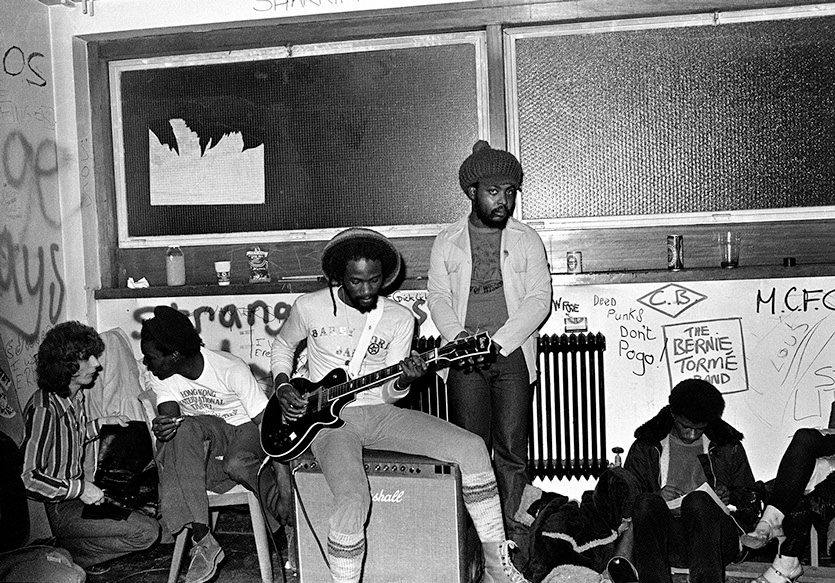

Syd Shelton’s pictures of Rock Against Racism (1976 – 1981) take us back to when the National Front marched with confidence and racism was rife. Shelton was one of many who hoped to defeat racism with music. Under the slogan ‘Love Music, Hate Racism’ acts with multicultural audiences like The Clash, Elvis Costello, Misty in Roots, Tom Robinson, Au Pairs and The Specials played for unity. Ska, punk and reggae bands shared the same stage. It was thrilling. And to some degree it worked.

Shelton recalls:

“In collaboration with UK reggae and punk bands, RAR members took on the orthodoxy through five carnivals and some 500 gigs throughout Britain. In those five years, the National Front went from a serious electoral threat into political oblivion.”

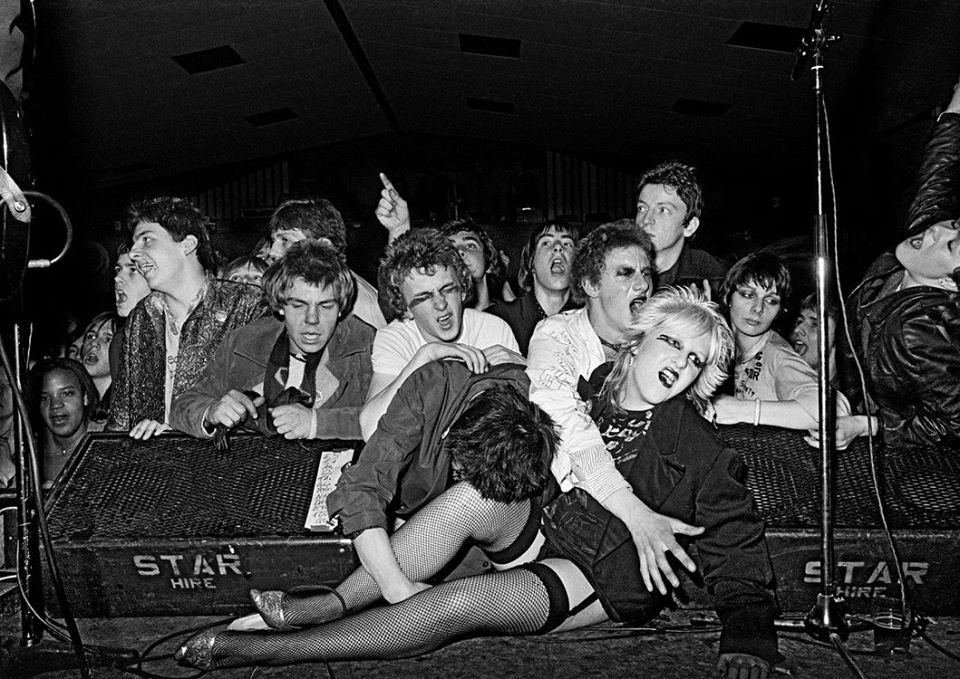

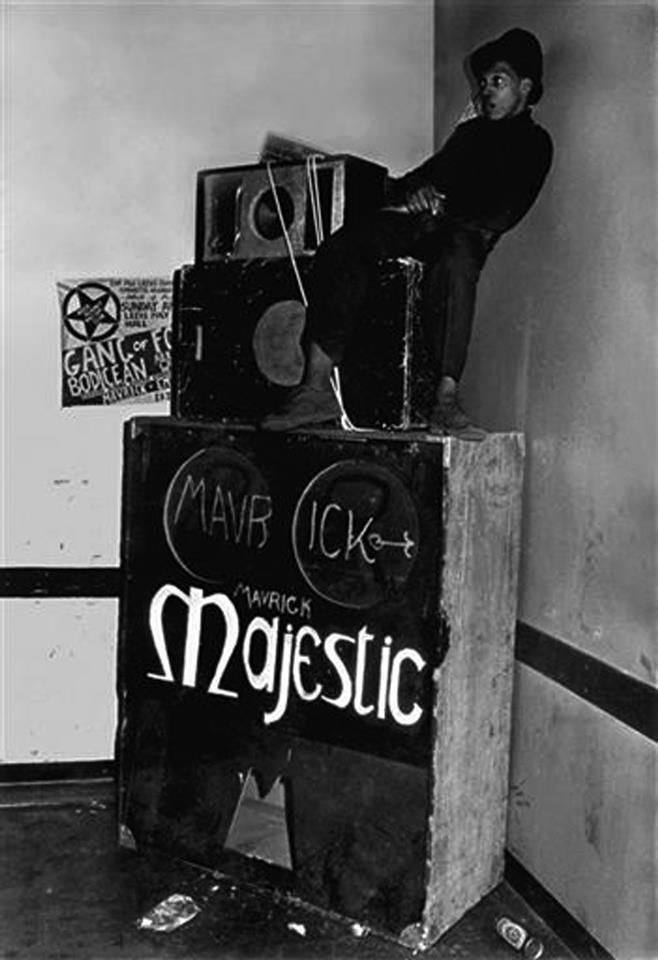

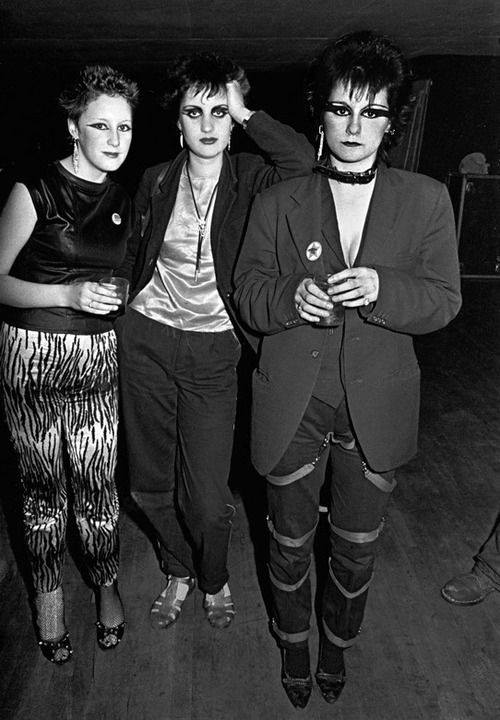

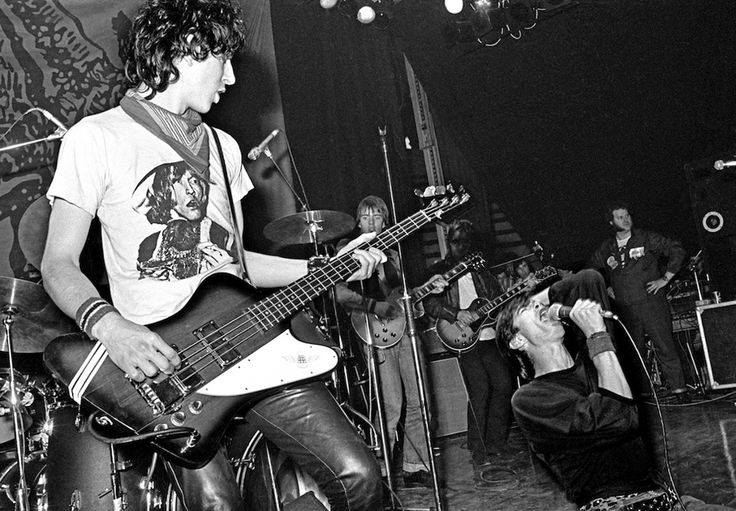

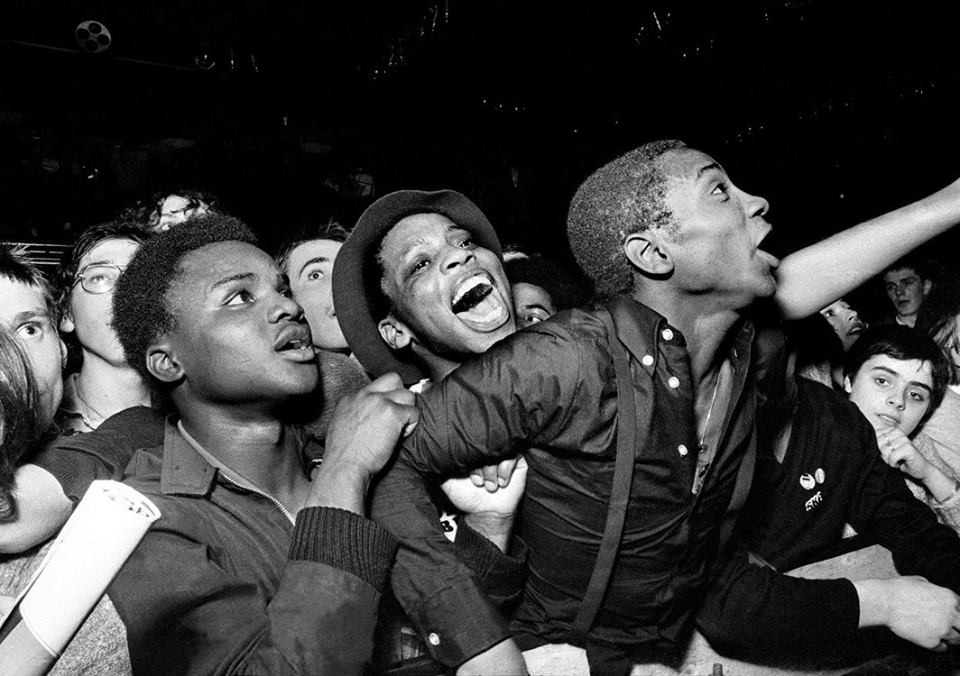

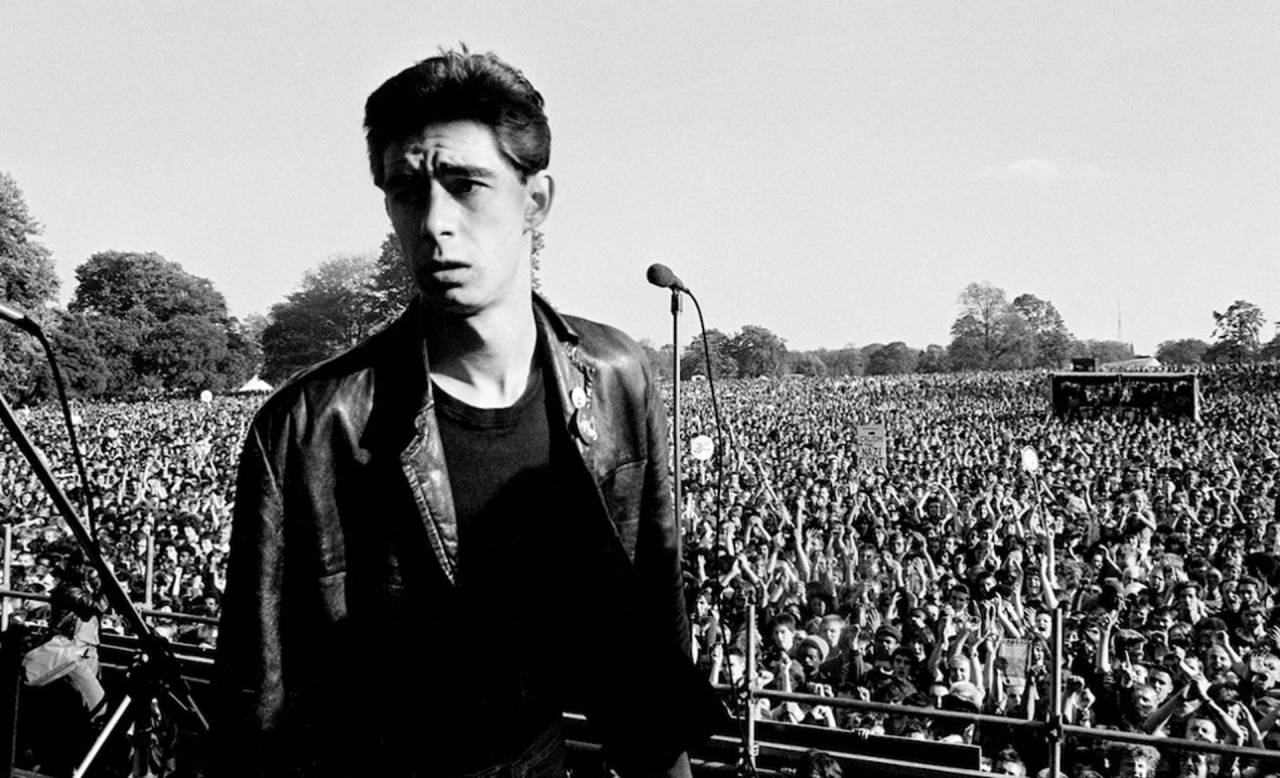

“The Rock Against Racism/Anti-Nazi League Carnival Against the Nazis was the last ever Specials gig before they split up and the shot is from the mosh pit.. I like its style narrative, which charts a journey from the rude boys via the skinheads back to the rude boys.” – Syd Shelton

Not every musician was onside. RAR was triggered by Eric Clapton, who on August 5 1976 told his audience at the Birmingham Odeon: “I think Enoch’s right … we should send them all back. Throw the wogs out! Keep Britain white!”

The Odeon in Birmingham was not too far from the Midland Hotel where in 1968 Tory MP Enoch Powell had made his infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. Many nodded in agreement. Some did far more:

The National Front had won 40 per cent of the votes in the spring elections in Blackburn. One month earlier an Asian teenager, Gurdip Singh Chaggar, had been murdered by a gang of white youths in Southall. ‘One down – a million to go’ was the response to the killing from John Kingsley Read of the National Front…

David Bowie, who three months earlier had been photographed apparently giving a Nazi salute in Victoria Station, told Cameron Crowe in the September 1976 edition of Playboy ‘… yes I believe very strongly in fascism. The only way we can speed up the sort of liberalism that’s hanging foul in the air… is a right-wing totally dictatorial tyranny…’ In that same interview Bowie claimed that ‘Adolf Hitler was one of the first rock stars.’

In September 1976 photographer Red Saunders wrote a reply. His letter was published in the pop music weeklies Sounds, NME and Melody Maker:

“When we read about Eric Clapton’s Birmingham concert when he urged support for Enoch Powell, we nearly puked. Come on Eric… you’ve been taking too much of the Daily Express stuff and you know you can’t handle it. Own up. Half your music is black. You’re rock music’s biggest colonist. You’re a good musician but where would you be without Blues and R&B? You’ve got to fight the racist poison otherwise you degenerate into the sewer with the rats and the money men who ripped off rock culture with their cheque books and plastic crap. We want to organise a rank and file movement against the racist poison music. We urge support for Rock Against Racism. Ps: Who shot the Sheriff, Eric? It sure as hell wasn’t you!”

A movement was born. In November 1976, Rock Against Racism held its first ever gig, featuring Carol Grimes, in the Princess Alice pub in east London.

RAR published Temporary Hoarding, a magazine that stated its aims in Issue 1 (via):

“We want Rebel music, street music. Music that breaks down people’s fear of one another. Crisis music. Now music. Music that knows who the real enemy is. Rock against Racism. Love Music Hate Racism.”

Darcus Howe:

“The atmosphere felt sharp. You knew you were making a stance. It was crucial: I lived in the area, I had got married there and my first daughter was born there, so I was part of the community. The National Front had come trying to terrorise us.

“The police put up barriers and cordoned us off so it ended up like a meeting in a park. The gathering was largely black people supported by young white activists. The slogan was ‘Don’t let them pass’.

“I was asked to speak right there on the spot. I was not on the list of speakers but [RAR campaigner] David Widgery said: ‘Give that man the megaphone.’ I always spoke in dulcet tones like a preacher from the pulpit. I said: ‘They haven’t come here to mobilise us to support them, they come here to terrorise.’ I delivered rhetoric about standing up, about the fact that black people in America were standing up and rhetoric about Africa.

“The major thing in my mind was, ‘Come what may, we are here to stay.’ Today it sounds ridiculous to say that but in those days it was the era of the campaign for repatriation and if the government weren’t going to do it, the National Front were going to do it. But in the end, they dropped their flags and ran away.”

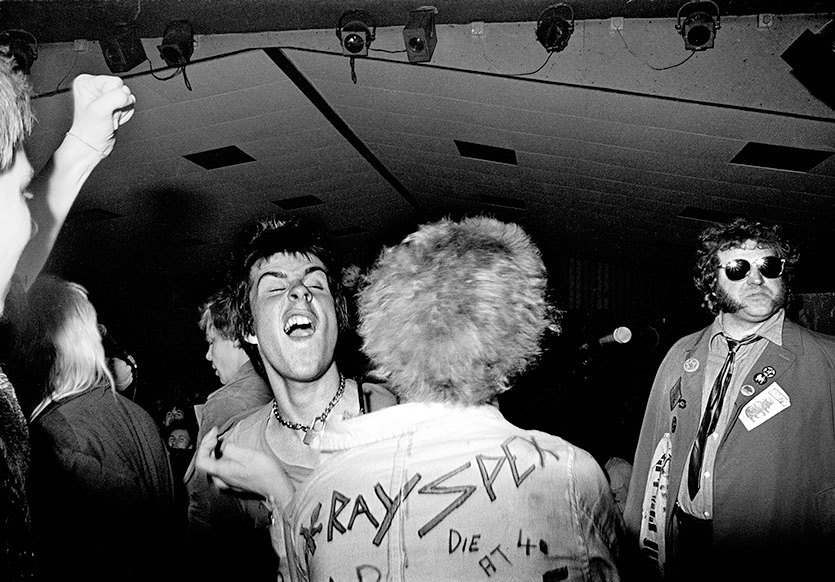

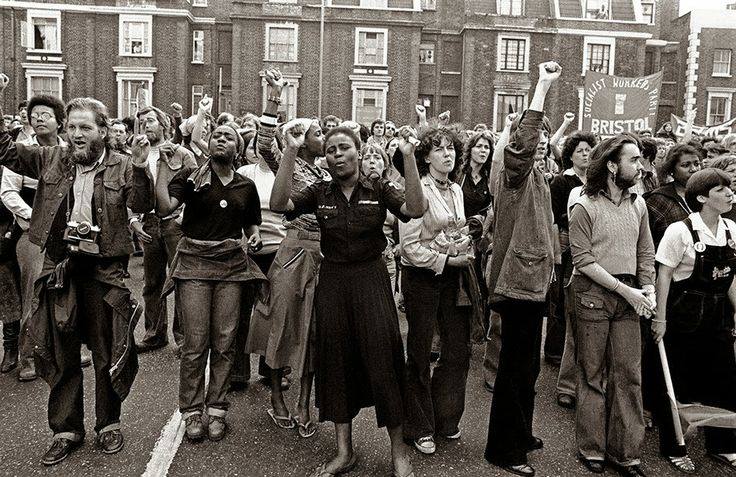

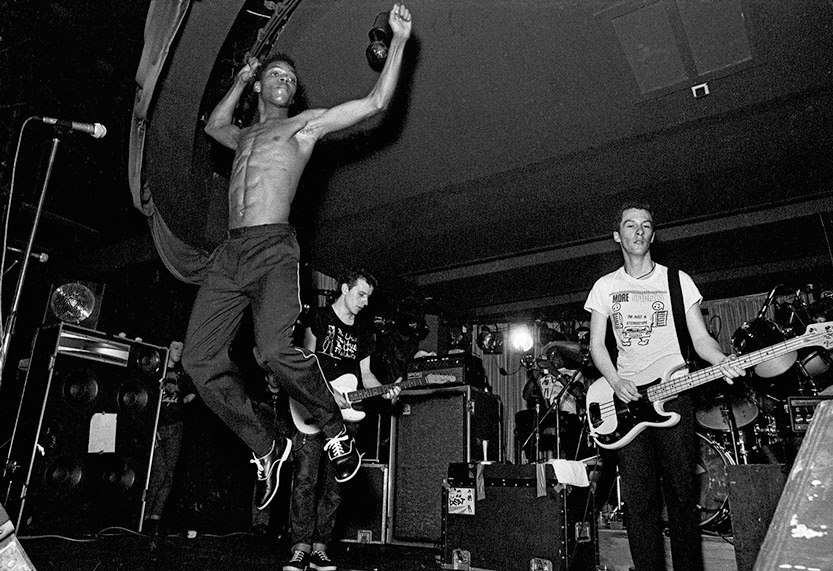

The apogee of this exciting movement came with a huge concert on 30 April 1978. Supporters were encouraged to convene at Trafalgar Square for a walk to Victoria Park in east London. The Clash, Steel Pulse, X-Ray Spex and the Tom Robinson Band were scheduled to play. Would anyone turn up, let alone walk seven miles from Westminster to an open-air concert in Hackney? “When I went down at 7am,” Shelton recalls, “there were already 10,000 people in the square.” By the time The Clash took the stage 80,000 were looking on. The place pulsated with energy.

Rock against Racism, smash it

Rock against Fascism, smash it

Rock against Nazism, me say smash it

I’ve come to the conclusion that

We’re gonna hunt yeh yeh yeh

The National Front – Yes we are,

We’re sonna kunt, yeh yeh yeh

The National Front

Cause they believe in apartheid

For that we gonna whop their hides

For all my people they cheated and lied

I won’t rest till I’m satisfiedThe National Front, Said we gonna hunt the National Front

Jah Pickney (Rock Against Racism) Steel Pulse

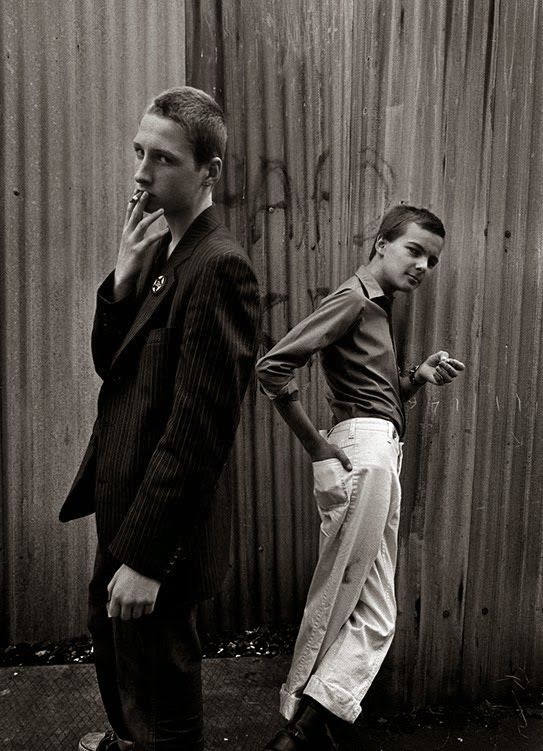

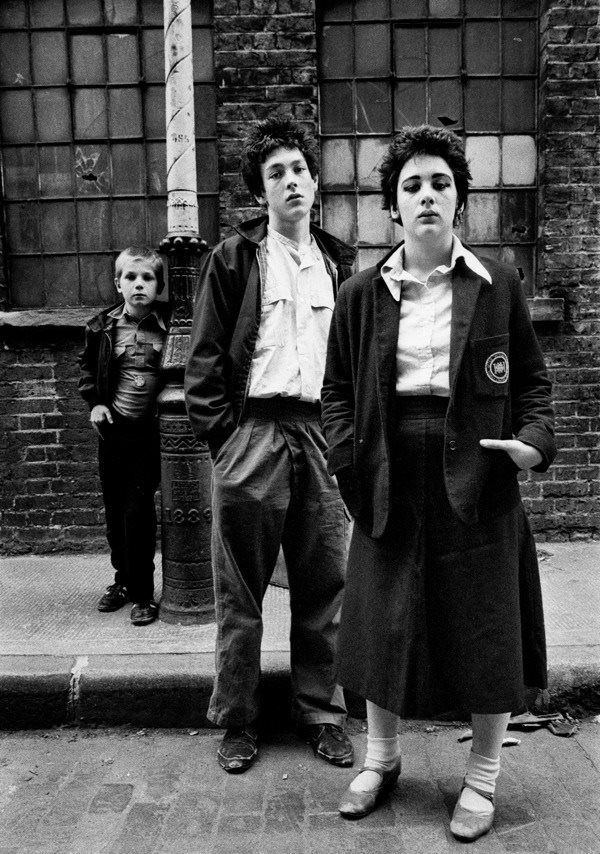

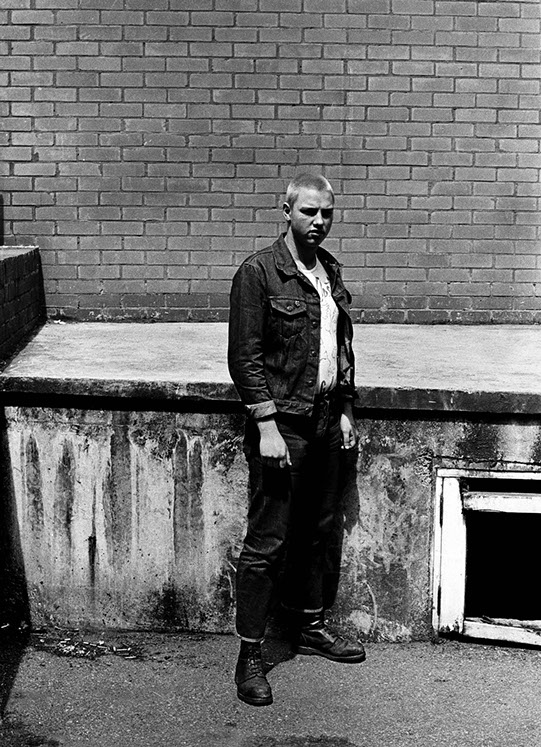

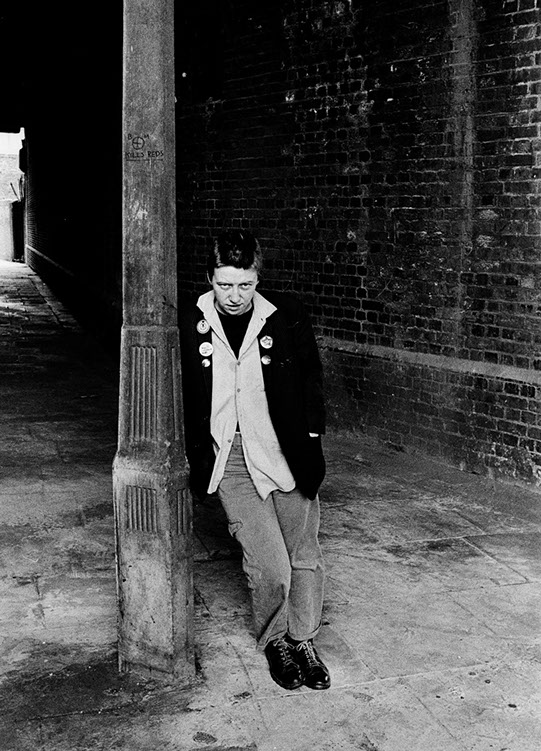

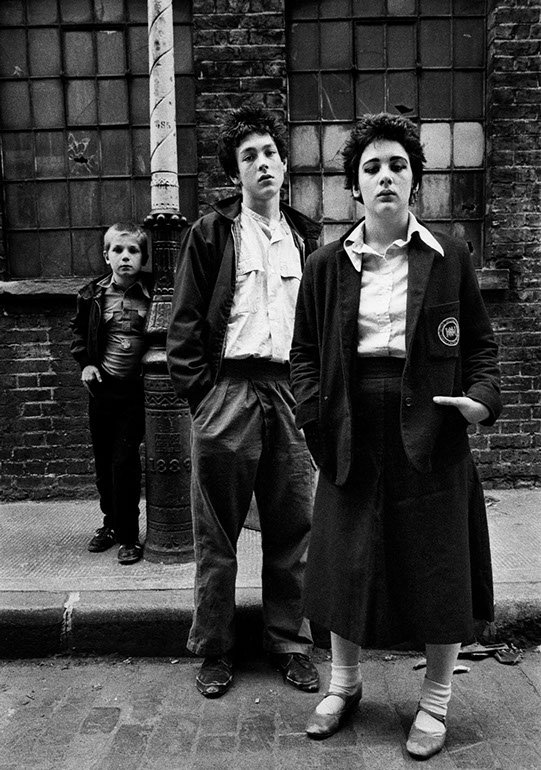

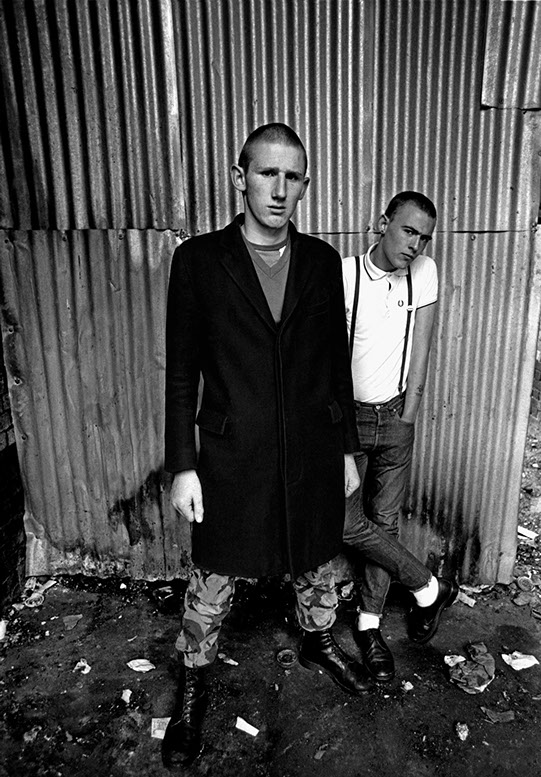

Skinheads, Petticoat Lane, East London, 1979: “I met these two guys at a shop called The Last Resort where they bought skinhead gear, Harrington jackets, Crombies, Doc Martens boots and Ben Sherman shirts. This was another slow shoot and it was only when I started to argue with them about racism that they started to give me some attitude. This was the last shot and they were getting really mad with me. I saw the guy at the front clenching his fists so I took the shot, said thanks and legged it as fast as I could.” – Syd Shelton=

All you punks and all you teds

National Front and natty dreads

Mods, rockers, hippies and skinheads

Keep on fighting till you’re dead.

– The Specials, Do the Dog

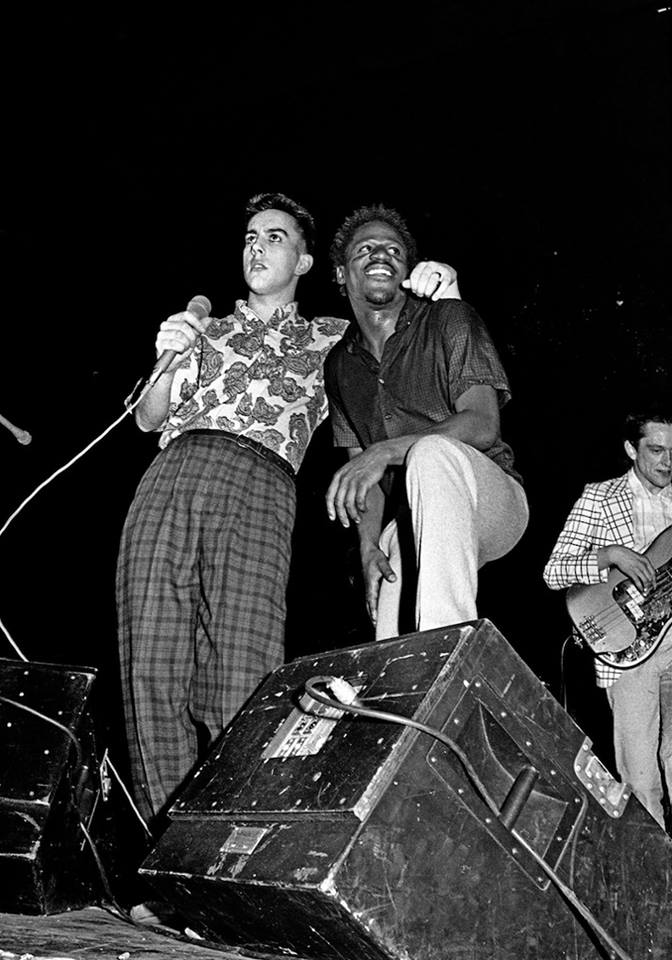

Terry Hall and Neville Staples of The Specials, Rock Against Racism and Anti-Nazi League Carnival, Potternewton Park, Leeds, 1981

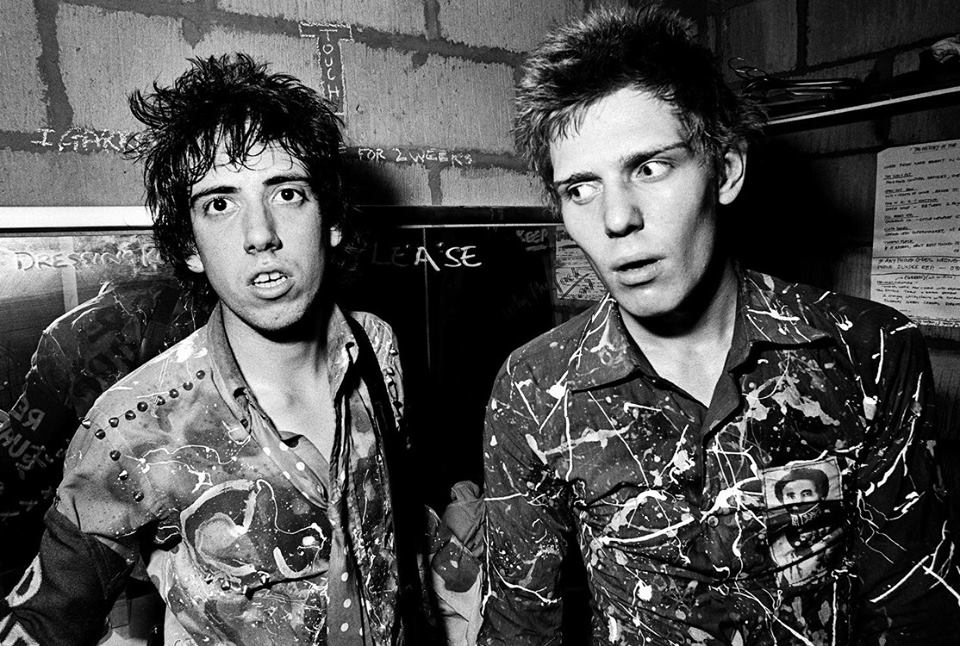

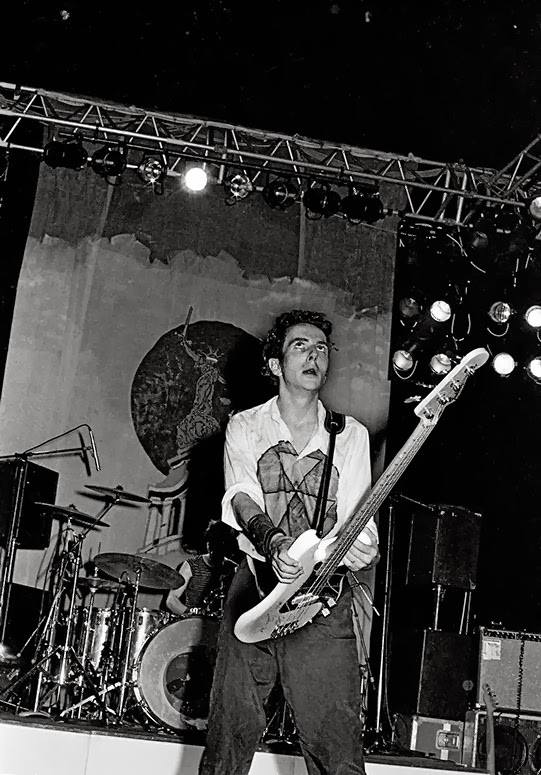

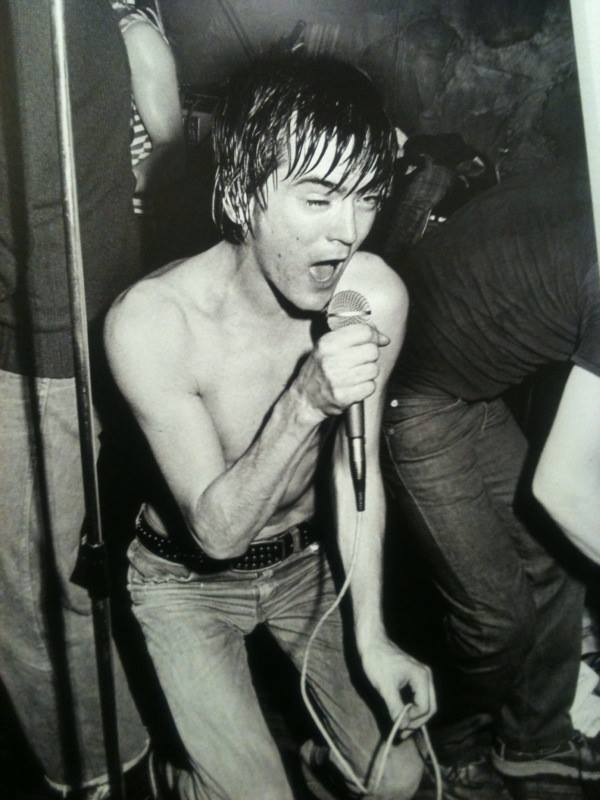

Carnival 2, Brockwell Park, Brixton, 24 September 1978: “Elvis Costello and the Attractions headlined the event. The rest of the line-up included Aswad, Misty in Roots and Stiff Little Fingers. Sham 69 were billed to play but due to death threats in reaction to their anti-racist stance, pulled out. Jimmy Percy, the lead singer, did appear and made a brave, passionate anti-racist speech to the Carnival crowd. I was on stage between Aswad and Elvis Costello’s sets and was reloading my cameras with film when Jimmy charged past me and grabbed the mike. I quickly sorted out my film and he turned away from the stage, his face stressed with emotion, and I hoped I had got the shot. I don’t see myself as a ‘decisive moment’ moment kind of photographer but this was one of those and I was itching to get into the darkroom to see if I had got it.” – Syd Shelton

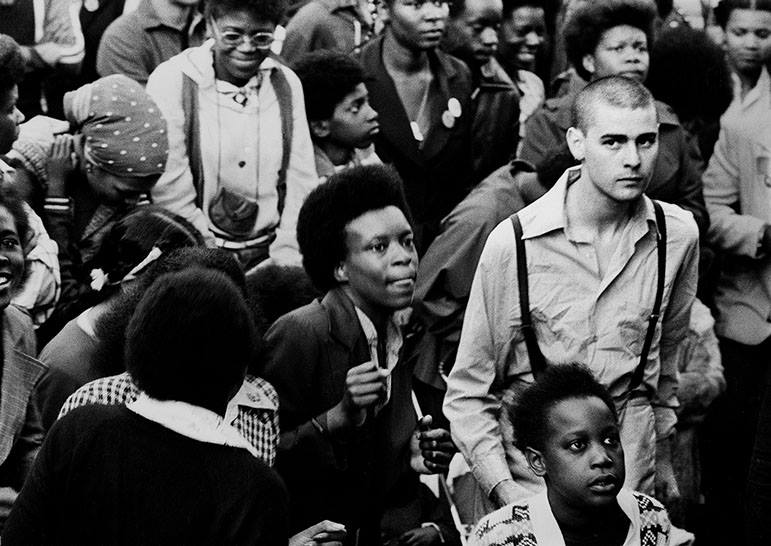

The crowd at the Rock Against Racism:Anti Nazi League Carnival 1, at London’s Victoria Park, 30 April 1978.

All pictures copyright of Syd Shelton

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.