A staple of dystopian sci-fi and space opera, the lawless city—teeming with refugees, runaways, smugglers, and all sorts of industrious types going about their business—has many real-life analogues. There are the anarchist pirate collectives of legend: Libertatia, most notably, a 17th-century Madagascar colony led by Captain Mission and featuring centrally in William S. Burroughs’ Cities of the Red Night and Ghost of Chance. Such places were said to be built on proto-communist principles. Fiercely anti-slavery, anti-monarchy, and anti-markets, the pirate colony “looks backward to the medieval commune and forward to the withering away of the state,” wrote A.L. Morton in The English Utopia.

Perhaps at the other end of the libertarian spectrum, there is Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong, torn down in the early ‘90s but for almost forty years a thriving experiment in unregulated, stateless free markets. In his mid-nineties Bridge Trilogy, William Gibson looked back to the just-demolished Kowloon Walled City—reconstructed in a virtual simulation—to see the future. It was “an outlaw place,” he writes in Idoru. “And more and more people crowded in; they built it up, higher. No rules, just building, just people living. Police wouldn’t go there. Drugs and whores and gambling. But people living too. Factories, restaurants. A city. No laws.”

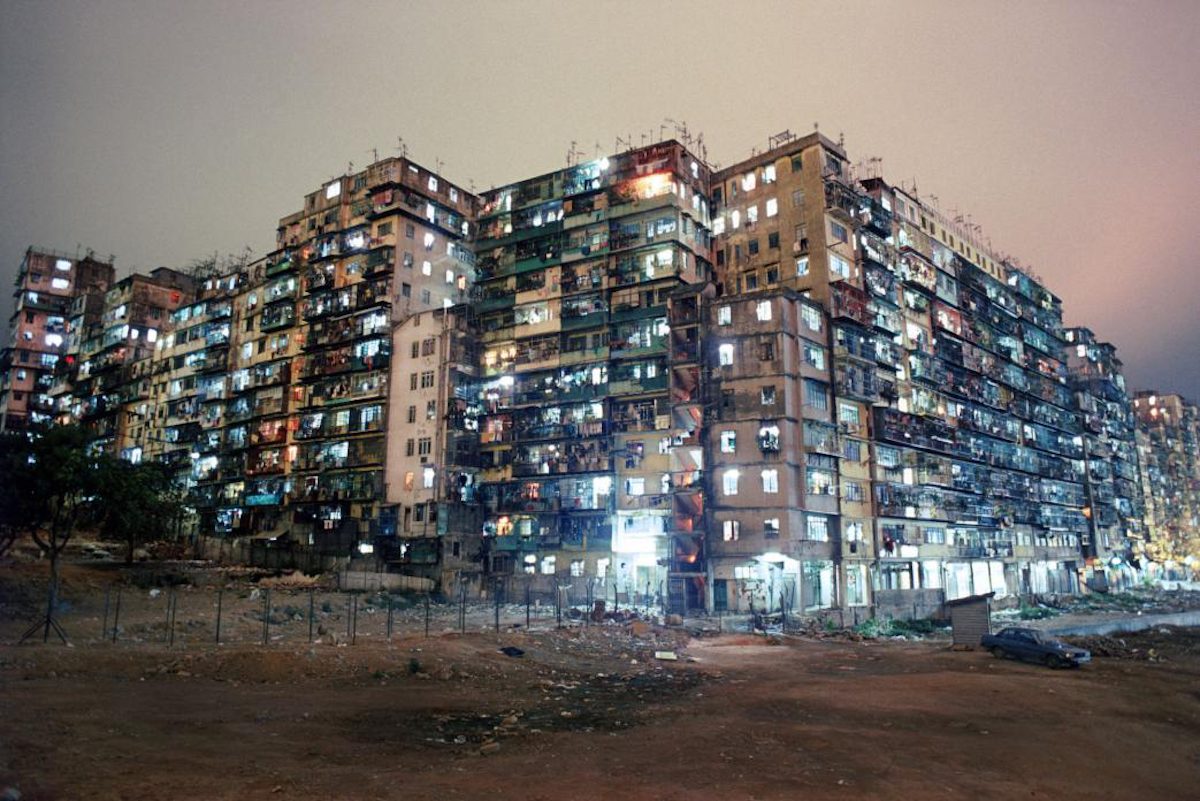

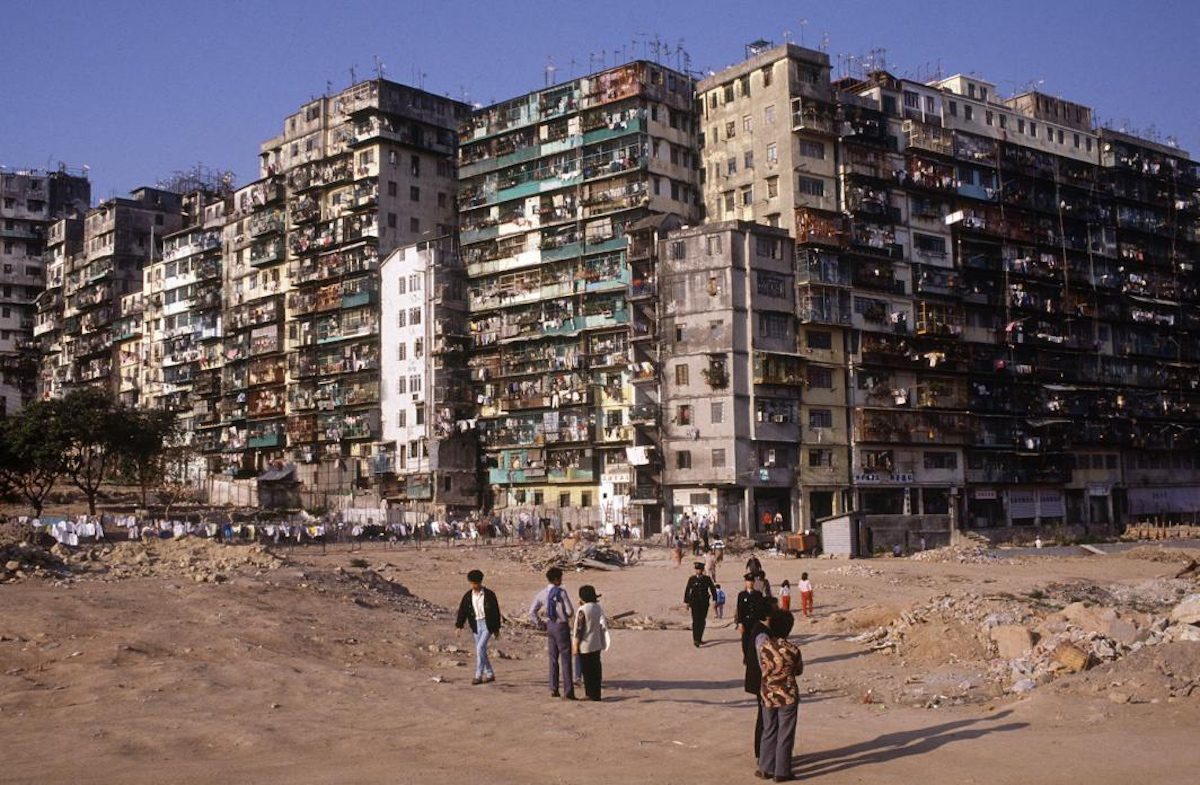

Kowloon Walled City “began as a Chinese military outpost,” writes Kelsey Campbell-Dollaghan at Gizmodo, “and emerged as a kind of no-man’s-land when England leased Hong Kong in 1898. The Japanese razed the site during World War II, and after the surrender, it became a magnet for refugees when neither England nor China wanted to deal with the burgeoning, ungoverned community.” From a steady stream of inhabitants pouring in during the late 1940s and 50s, a squatter village grew into a thriving 6.4-acre city with 33,000 residents, the most densely populated area in the world.

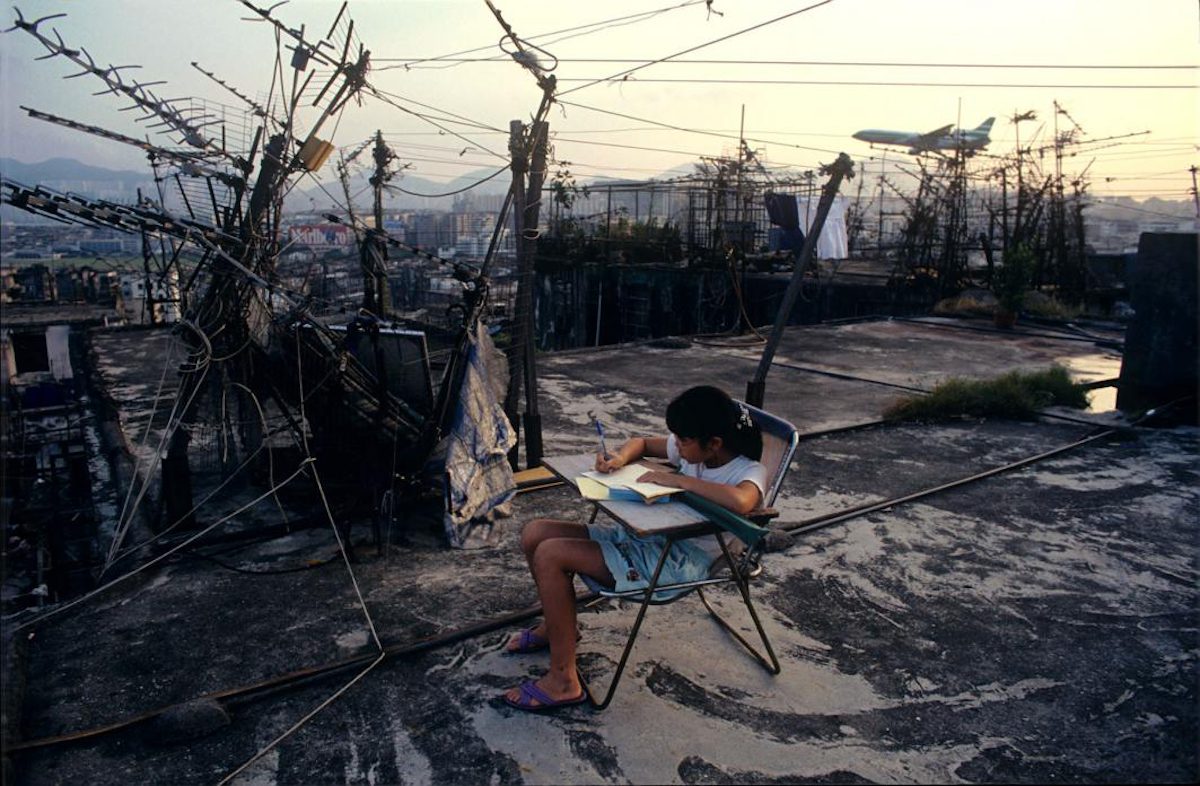

Having nowhere else to go, residents, built up, points out Atlas Obscura, in an excerpt from James Crawford’s Fallen Glory: The Lives and Deaths of History’s Greatest Buldings, constructing 350 towers, “almost all between 10 and 14 stories high,” the upper limit determined by the nearby airport.

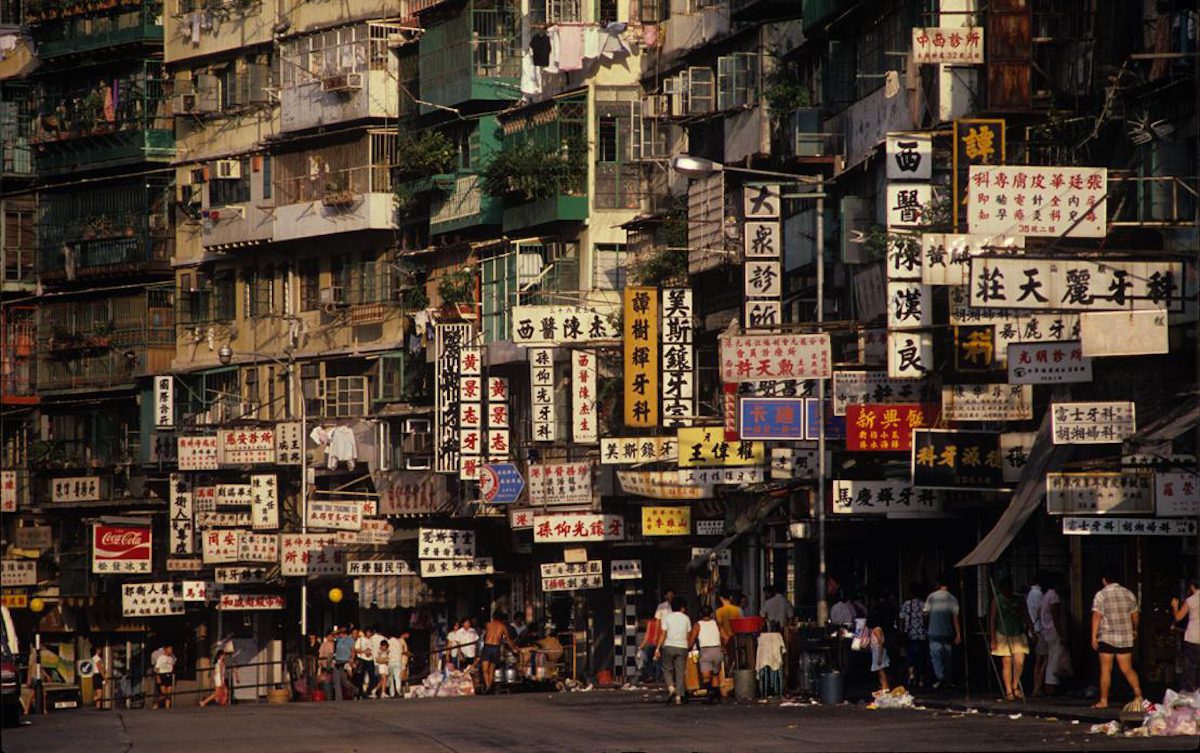

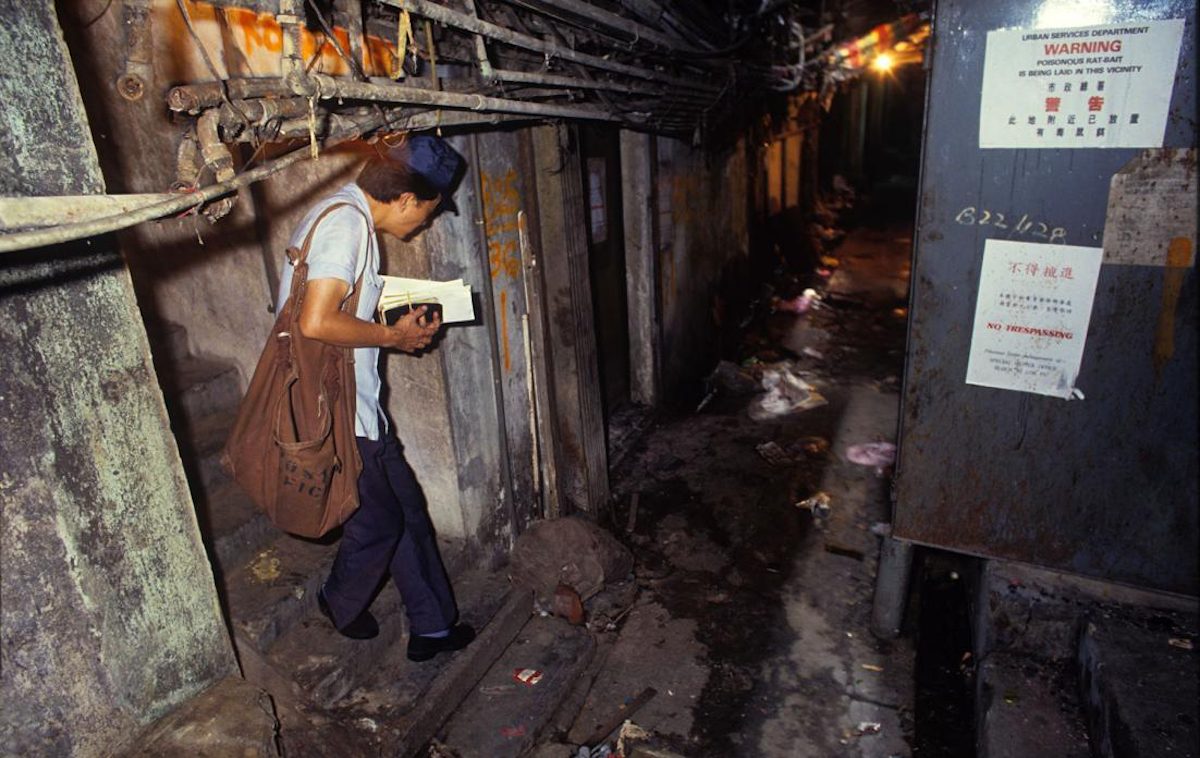

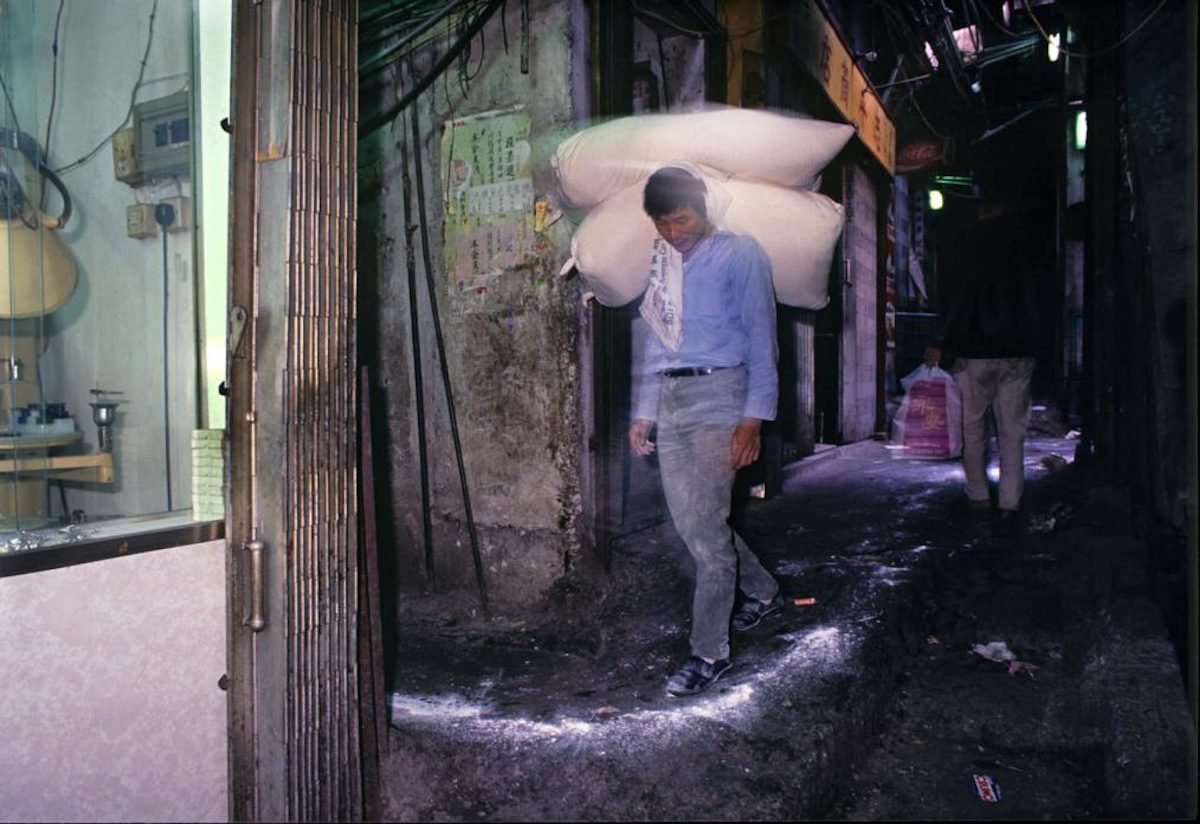

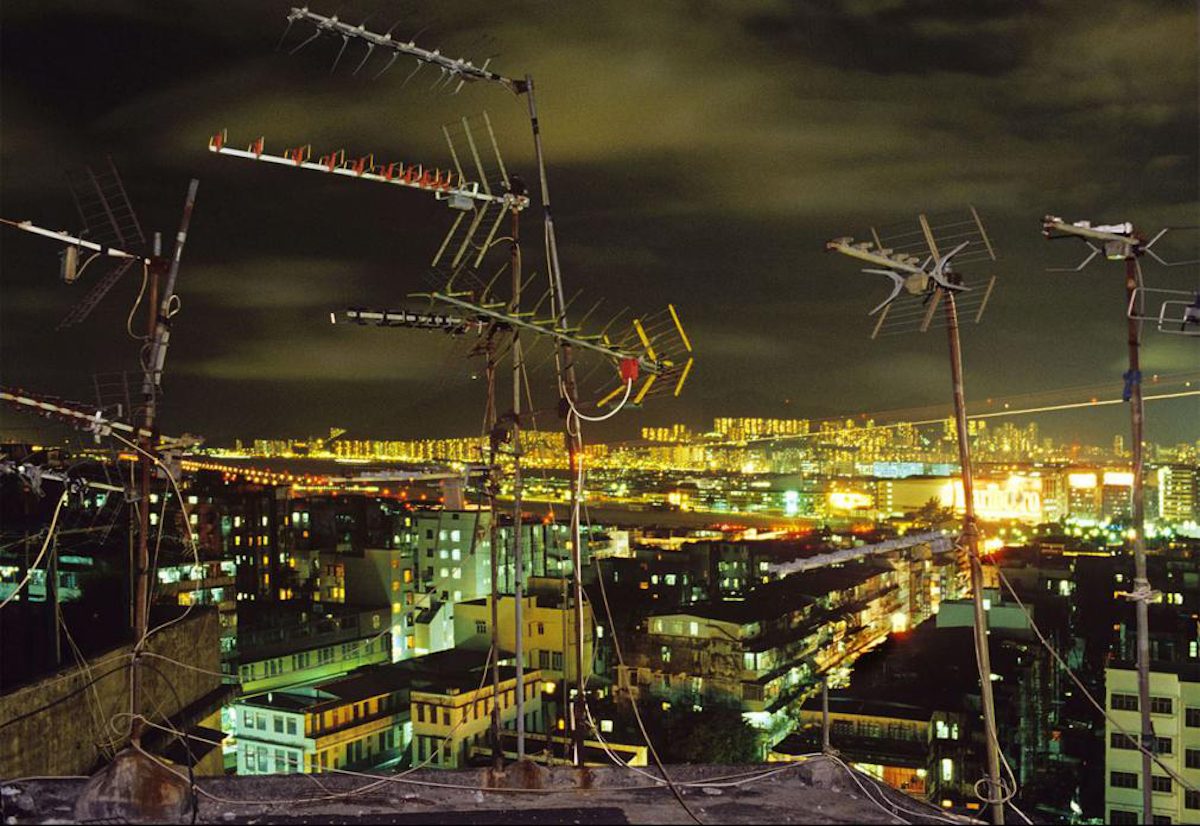

The city’s many tall, narrow tower blocks were packed tight against each other—so tight as to make the whole place seem like one massive structure: part architecture, part organism. There was little uniformity of shape, height, or building material. Cast-iron balconies lurched against brick annexes and concrete walls. Wiring and cables covered every surface: running vertically from ground level up to forests of rooftop television aerials, or stretching horizontally like innumerable rolls of dark twine that seemed almost to bind the buildings together. Entering the city meant leaving daylight behind. There were hundreds of alleyways, most just a few feet wide. Some routes cut below buildings, while other tunnels were formed by the accumulation of refuse tossed out of windows and onto wire netting strung between tower blocks. Thousands of metal and plastic water pipes ran along walls and ceilings, most of them leaking and corroded. As protection against the relentless drips that fell in the alleyways, a hat was standard issue for the city’s postman. Many residents chose to use umbrellas.

Triad-run opium dens, drug markets, and brothels thrived, but so too did dentists and butchers and a factory that made rubber plungers, founded and operated by just two men. The city was as famous for its noodle houses as its plentiful supply of canine cuisine, illegal elsewhere in Hong Kong. “This was an anarchist society, self-regulating and self-determining. It was a colony within a colony, a city within a city, a tiny block of territory at once contested and neglected. It was known as Kowloon Walled City. But locals called it something else. Hak Nam—the City of Darkness.”

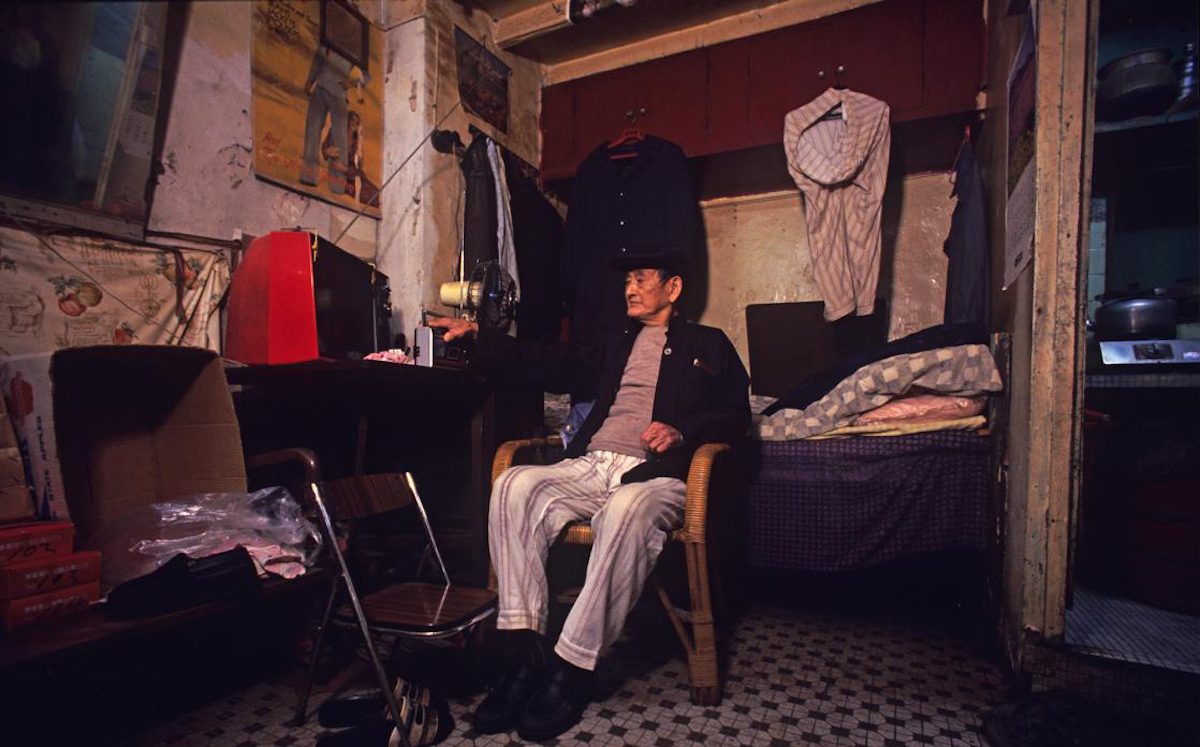

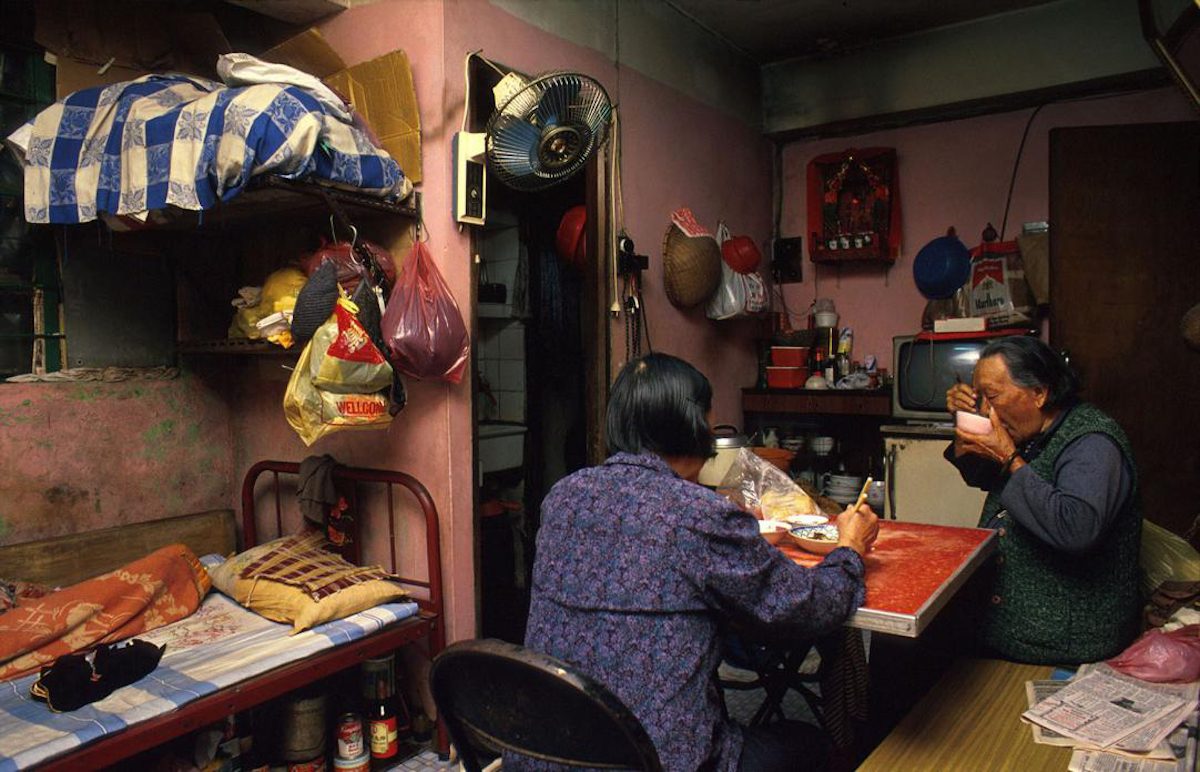

The labyrinthine streets, walkways, balconies, and alleyways beneath the mad jumble of buildings admitted no daylight. The only place to see the sun was on the rooftops. When Canadian photographer Greg Girard began exploring the city in 1987, the year it was first slated for demolition, it had become considerably safer than in years past. “The city normalized,” he says, “but the reputation stayed until the end. It was a place your parents told you to never go to.” Girard’s photos, published in photo book called City of Darkness Revisited with an essay by Ian Lambot, don’t shy away from the profound degrees of crime and grime. But they tell many other stories of Kowloon Walled City as well.

Though it is usually described by Westerners, writes Sharon Lam, “as ‘post-apocalyptic,’ ‘scary’ and ‘crazy,’” Kowloon was a place where thousands of families lived happily, despite squalid conditions. “The surprising liveliness and community of the Walled City shows that when free from law and liability things aren’t going to be that great, but they do not have to be an entire failure.” Girard’s documents of its final years show ordinary domestic scenes—and the daily routine of the city’s only postman—juxtaposed with what Jung Joon Lee describes as “drug dens, black market commerce, unlicensed medical practices, sweatshops, gang operations, and murders.”

In 1987, an administrative decision to demolish the city was made, undergoing a multiphase process to its completion in 1993. Tens of thousands of residents and workers in the Walled City were relocated and laid off, some with enough compensation to restart their lives but most without. With everybody gone and the structures razed—and the public’s attention now on the 1997 return of the former British colony to the People’s Republic of China—the city passed into the arena of reminiscence.

All that remains of Kowloon Walled City is a commemorative park. “It is not a well advertised or well heard of tourist attraction,” writes Lam, “nor is it a place of local pride.” This is not, however, due to “political embarrassment, but because it is culturally unremarkable.” While Westerners remember Kowloon as a dream, or nightmare, of dystopian anarchism, many former residents recall it as a “happier time,” and as the place to get the best noodles and fish balls in Hong Kong.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.