“The public life of liberal Hollywood comprises a kind of dictatorship of good intentions, a social contract in which actual and irreconcilable disagreement is as taboo as failure or bad teeth, a climate devoid of irony.” – Joan Didion

Hollywood has issues. It has issues with race, age, diversity and sex. Every year the same story of bigotry in Tinseltown rides high on the news cycle as Oscar season wafts in. Are we supposed to care? Hollywood celebrates and epitomises the ossification of taste at its televised AGM. The cool kids aren’t bothered. The smug moral correctness that pervades Hollywood produces self-aggrandising ‘Oscar-worthy’ films, washed with trite progressive messages – vanity movies in which the actors say the ‘challenging’ words on cue and gurn a sentiment but lack the concomitant brain function to make it authentic. Hollywood doesn’t go in for the hard stuff; it does cosy.

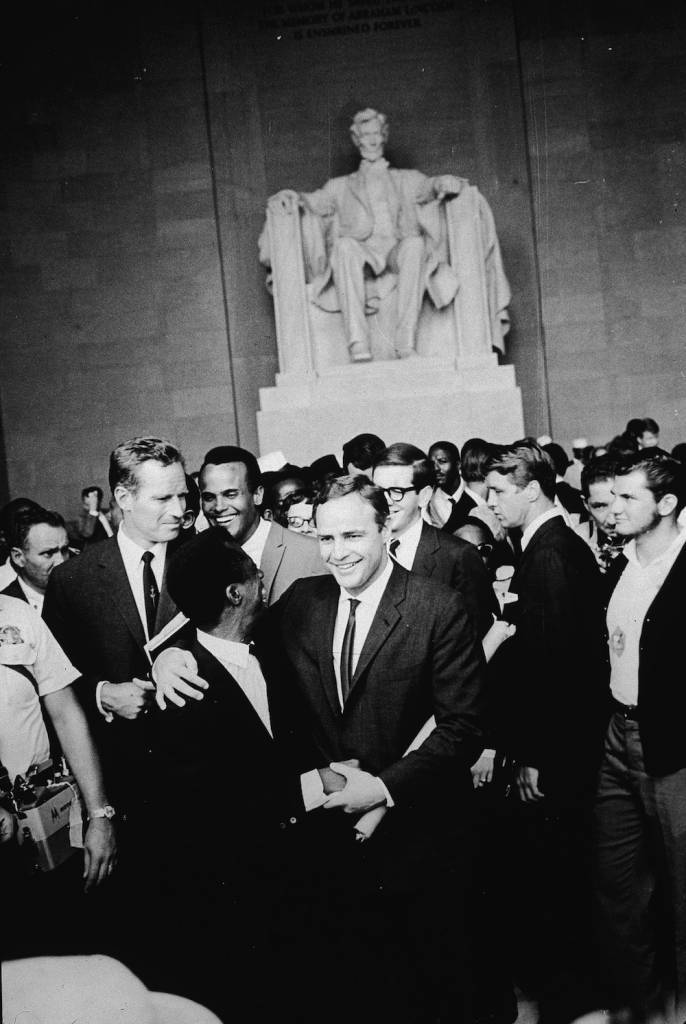

Actor Marlon Brando speaks to the writer James Baldwin at a civil rights rally August 28, 1963 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by National Archive/Newsmakers)

Joan Didion trained her incisive eye on Hollywood. Her words on Woody Allen’s late 1970s films resonate today. Woody’s works boast the “vacant fervour” Hollywood does so well. Didion wrote:

“People in Manhattan are constantly creating these real unnecessary neurotic problems for themselves that keep them from dealing with more terrifying unsolvable problems about the universe.”

For Manhattan, read Hollywood.

American actor Marlon Brando (1924 – 2004) stands with his arm around poet James Baldwin, surrounded by actors Charlton Heston (L), Harry Belafonte and others gathered at the Lincoln Memorial during the Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C., August 28, 1963. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In her essay Good Citizens (1968 – 1970), Didion writes on the “vanity of perceiving social life as a problem to be solved by the good will of individuals”:

Politics are not widely considered a legitimate source of amusement in Hollywood, where the borrowed rhetoric by which political ideas are reduced to choices between the good (equality is good) and the bad (genocide is bad) tends to make even the most casual political small talk resemble a rally…

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” someone said to me at dinner not long ago, and before we had finished our fraises des bois he had advised me as well that “no man is an island.” As a matter of fact I hear that no man is an island once or twice a week, quite often from people who think they are quoting Ernest Hemingway. “What a sacrifice on the altar of nationalism,” I heard an actor say about the death in a plane crash of the president of the Philippines. It is a way of talking that tends to preclude further discussion, which may well be its intention: the public life of liberal Hollywood comprises a kind of dictatorship of good intentions, a social contract in which actual and irreconcilable disagreement is as taboo as failure or bad teeth, a climate devoid of irony.

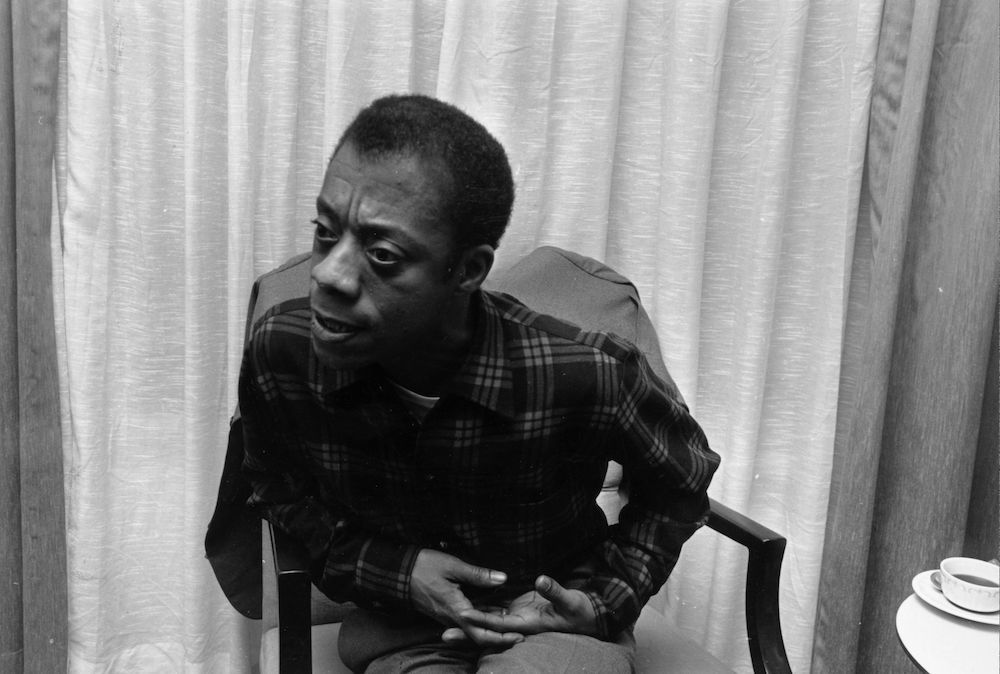

American writer and Civil Rights activist James Baldwin (1924 – 1987). (Photo by Townsend/Getty Images)

Christina McCausland adds:

Didion explores a particular form of impotent optimism that permeates California’s political and religious efforts. She explicitly criticizes this mindset in “Good Citizens,” where she characterizes these undertakings as possessing a sort of cinematic shallowness, and compares the Californians’ hopeful efforts to the myths of American popular and political culture. She also returns to her oft-explored theme of our attempts to impose widely-accepted narrative lines onto life’s events. She manages to capture the absurdity of the mindset and make her judgment clear without an overly harsh or sermonizing tone.

A group of men in the coal mining area of Scott’s Run, West Virginia. (Photo by Ben Shahn/Getty Images)

Didion searched for an example. She found the epitome in a 1968 debate staged at Eugene’s, Beverly Hills – a venue opened by supporters of Senator Eugene McCarthy; a place of Ben Shahn posters and The Family of Man sensibilities ). The talk revolved around moves to turn William Styron’s best-selling novel The Confessions of Nat Turner into a 20th Century Fox film. Amid protests the film was shelved.

The book is an account of an 1831 slave revolt in Southampton County, Va., narrated in Turner’s voice. At one point, black Nat expresses his love for a maiden every bit as white as Styron.

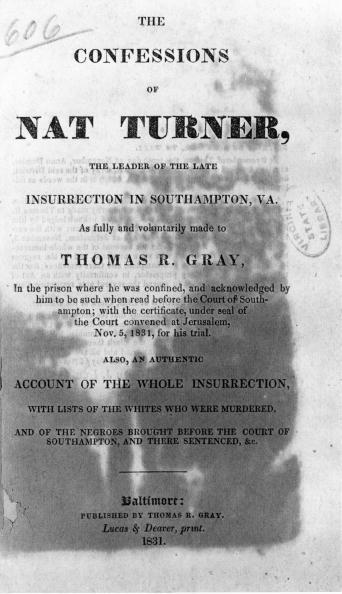

Document of the confessions of Nat Turner, the leader of the last insurrection in Southampton, Virginia USA November 5 1831.

American slave leader Nat Turner and his companions are shown in a wooded area, 1831. Turner led an uprising of slaves that resulted in the death of more than 50 white people. He was tried, convicted, and hanged in the state of Virginia.

Jess Row has more:

The Confessions of Nat Turner is based, very loosely, on a “confession” Turner gave to his court-appointed lawyer, Thomas Gray, shortly before his execution. Gray later published the confession. Styron wrote that the Turner he found in Gray’s text was a “dangerous religious lunatic… a psychopathic monster”; rather than expand on the historical record, he chose to write a meditation on history, giving him “dimensions of humanity that were almost totally absent in the documentary evidence.”

Members of the Kennedy family at the funeral of assassinated president John F. Kennedy at Washington DC. From left: Senator Edward Kennedy, Caroline Kennedy, (aged 6), Jackie Kennedy (1929 – 1994), Attorney General Robert Kennedy and John Kennedy (1960 – 1999) (aged 3). (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Styron debated his book’s worth with the actor Ossie Davis, who accused the text of inciting racism. Styron denied the charge. He would not falter. Here was the writer who worked beneath a quotation from Flaubert displayed on the wall of his study: “Be regular and orderly in your life like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work”. Creativity does not seek righteous compliance.

Styron’s friend James Baldwin, who had written the influential novel Another Country, acted as middleman. Is the Pulitzer Prize winning Confessions a “racist book”? You can hear the exchange hereunder. It’s worth noting that this occurred one week before Robert Kennedy’s death, when the Civil Rights movement was to the fore:

Didion reviewed the exchange: (via)

[The evening’s] curious vanity and irrelevance stay with me, if only because those qualities characterize so many of Hollywood’s best intentions. Social problems present themselves to many of these people in terms of a scenario, in which, once certain key scenes are licked (the confrontation on the courthouse steps, the revelation that the opposition leader has an anti-Semitic past, the presentation of the bill of participants to the President, a Henry Fonda cameo), the plot will proceed inexorably to an upbeat fade. Marlon Brando does not, in a well-plotted motion picture, picket San Quentin in vain: what we are talking about here is faith in a dramatic convention. Things “happen” in motion pictures. There is always a resolution, always a strong cause-effect dramatic line, and to perceive the world in those terms is to assume an ending for every social scenario… If the poor people march on Washington and camp out, there to receive bundles of clothes gathered on the Fox lot by Barbra Streisand, then some good must come of it (the script here has a great many dramatic staples, not the least of them in a sentimental notion of Washington as an open forum, (Mr. Deeds Goes to Washington), and doubts have no place in the story.

Like the literary fiction, the movie is a story. It is not real. Didion nails this confusing of fact with storytelling in her appraisal of the Women’s Liberation Movement:

“The idea that fiction has certain irreducible ambiguities seemed never to occur to these women, nor should it have, for fiction is in most ways hostile to ideology.”

The simple like it simple. After all, Hollywood films run for around two hours. They never do show the big picture.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.