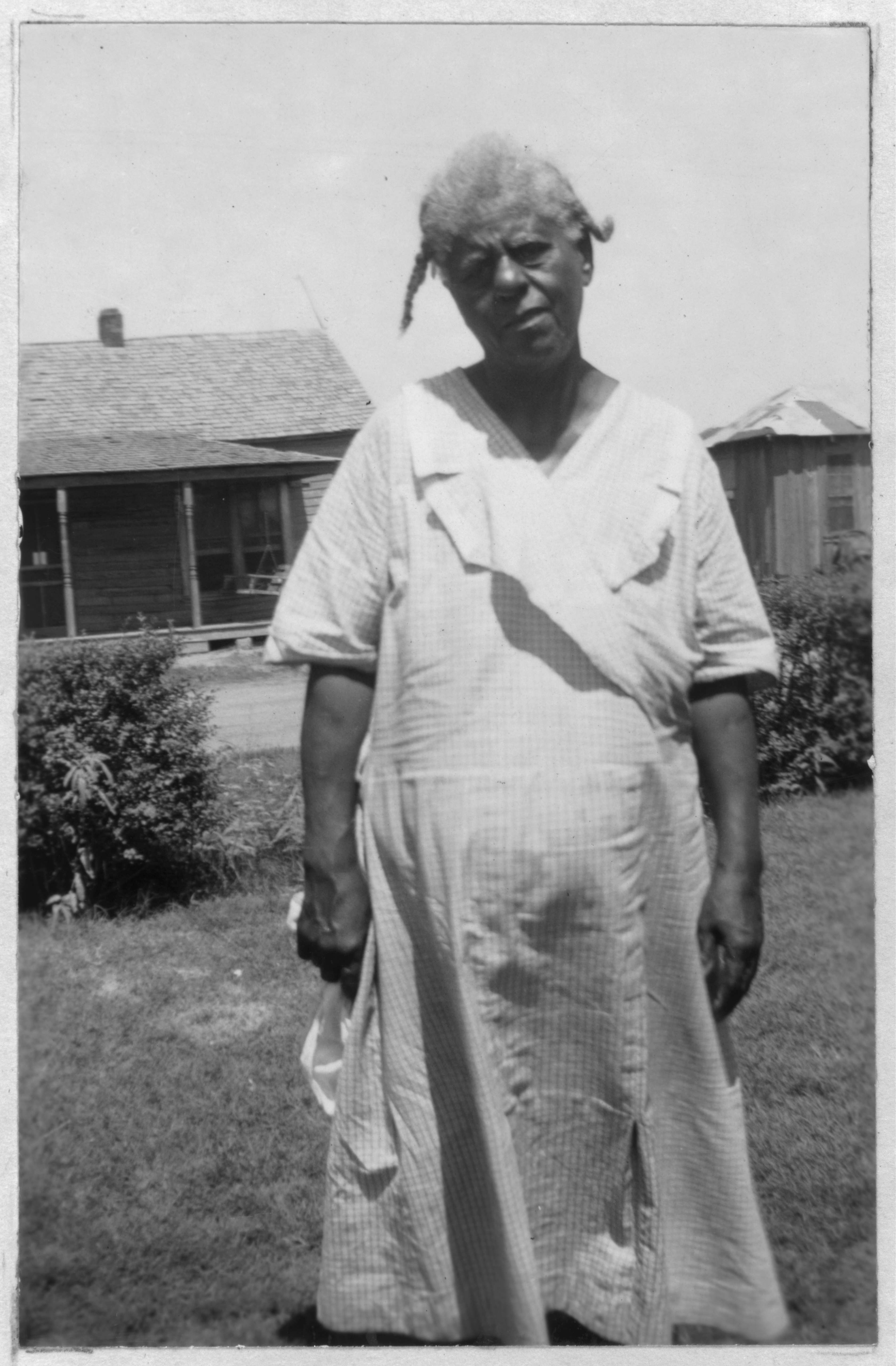

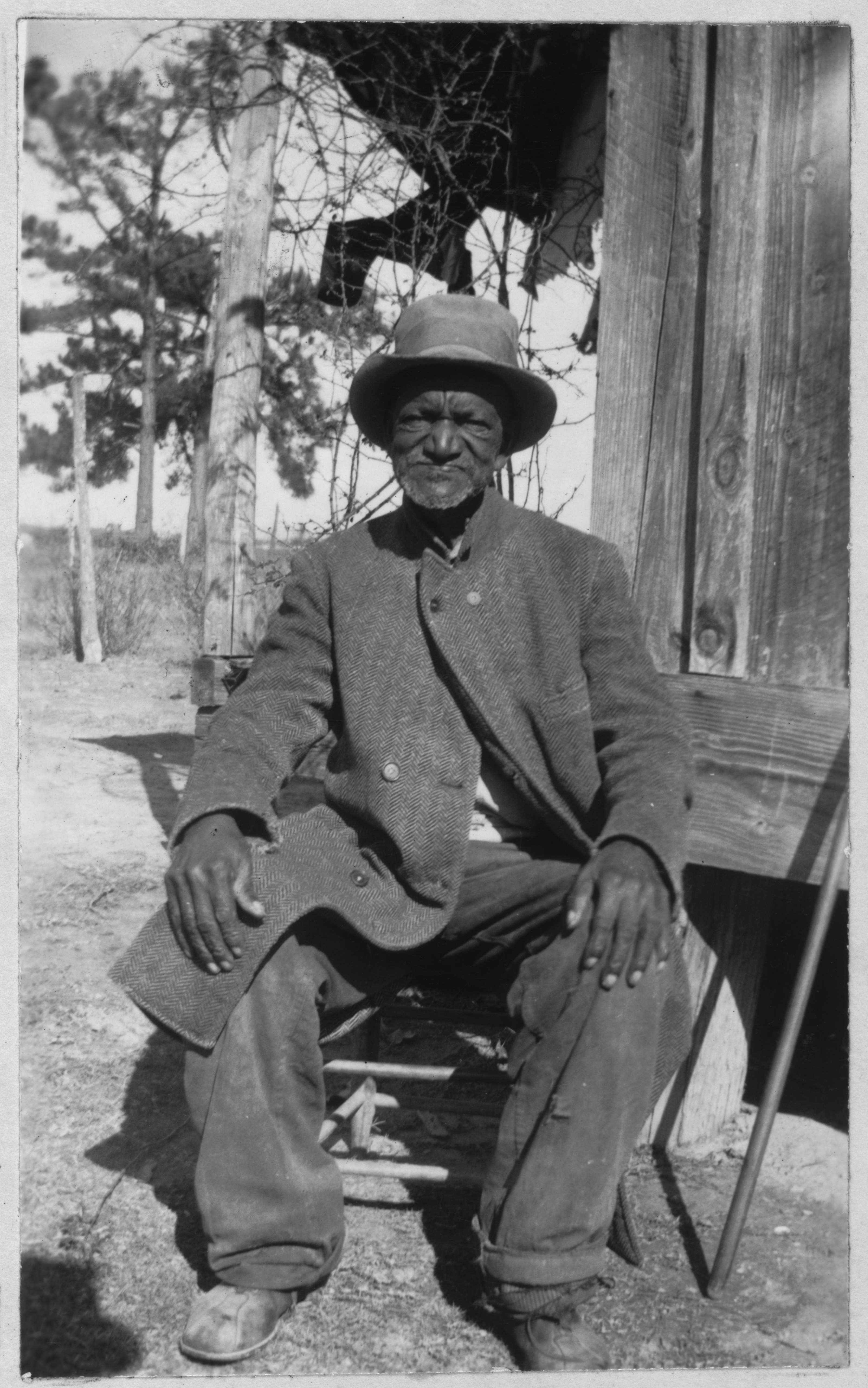

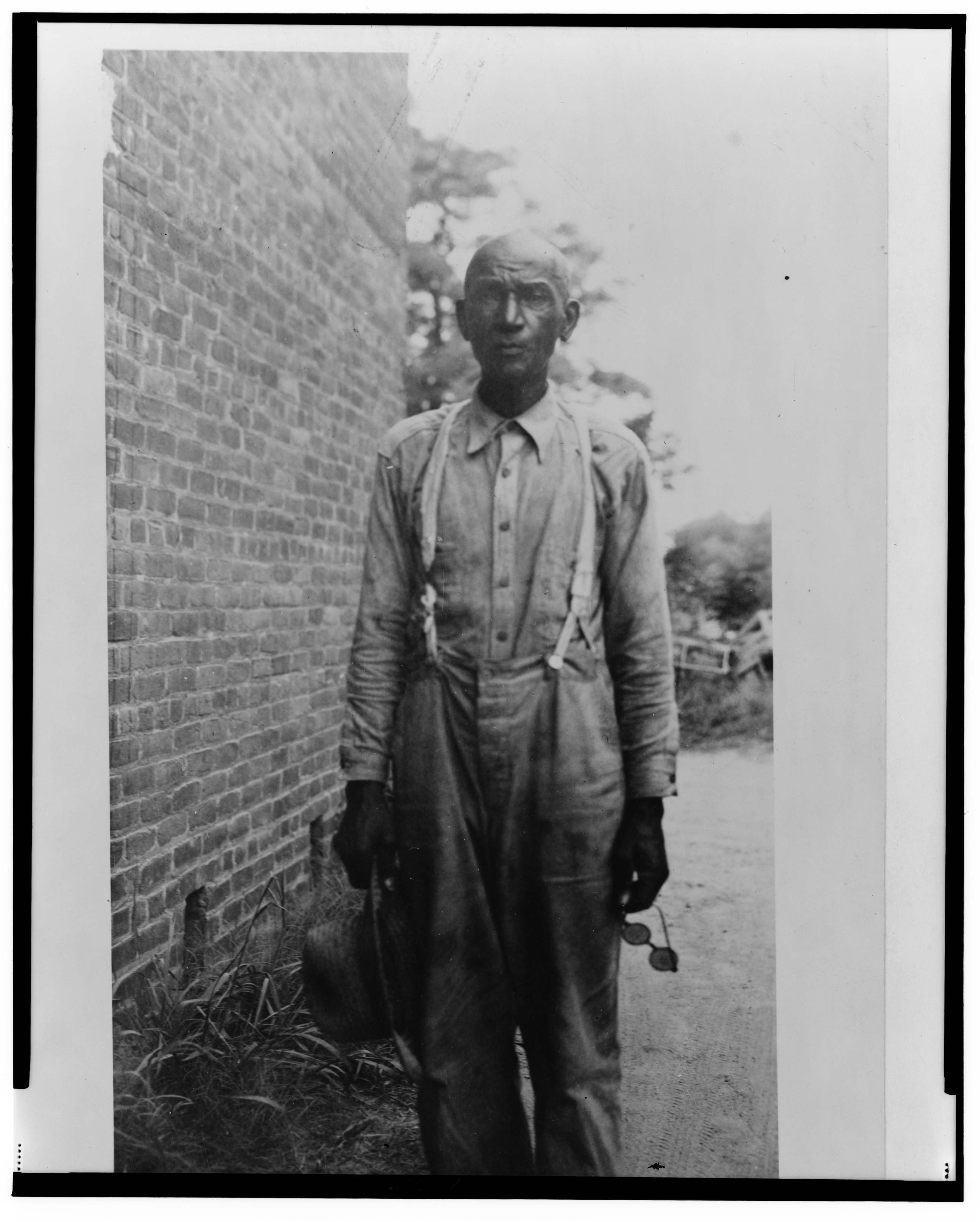

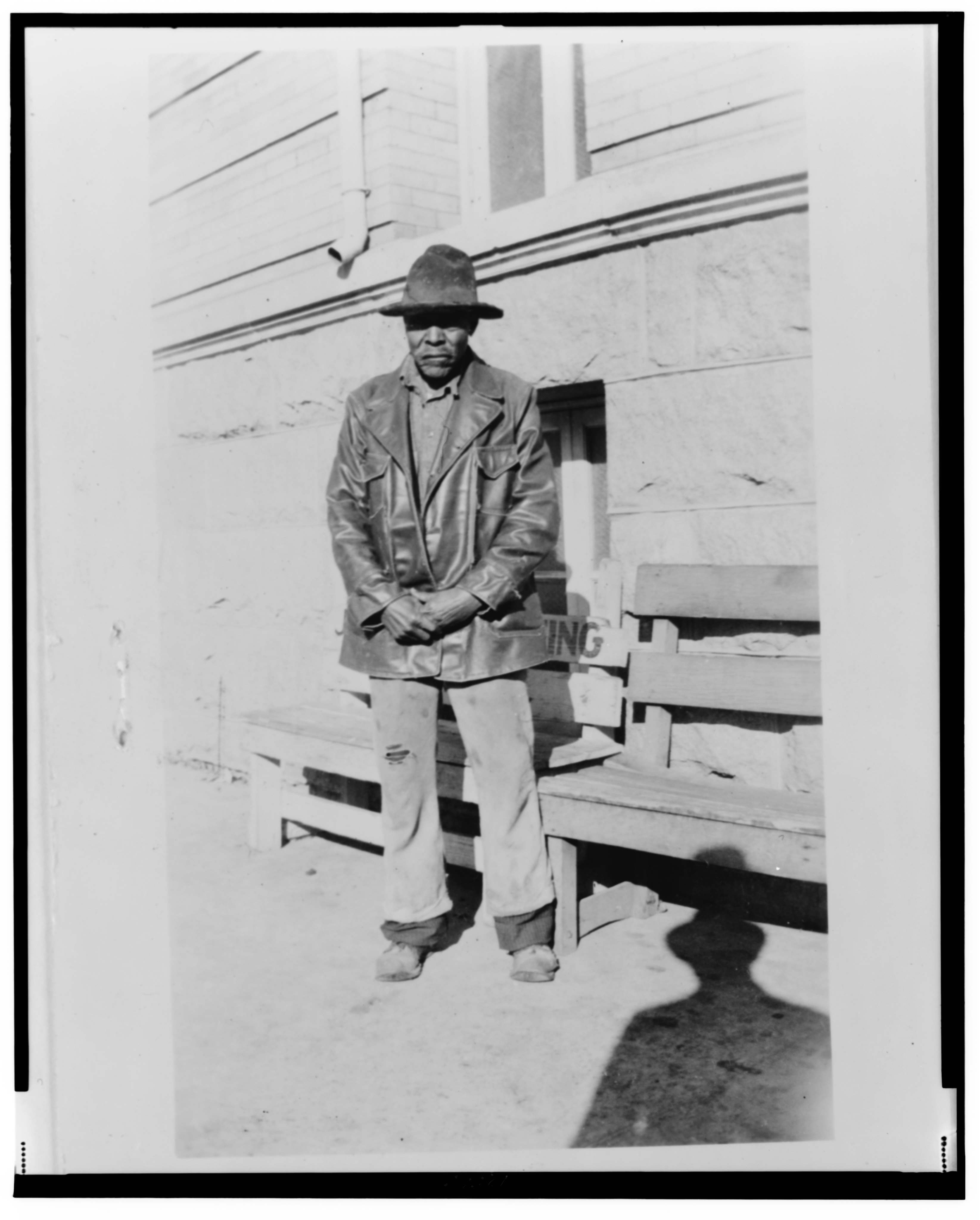

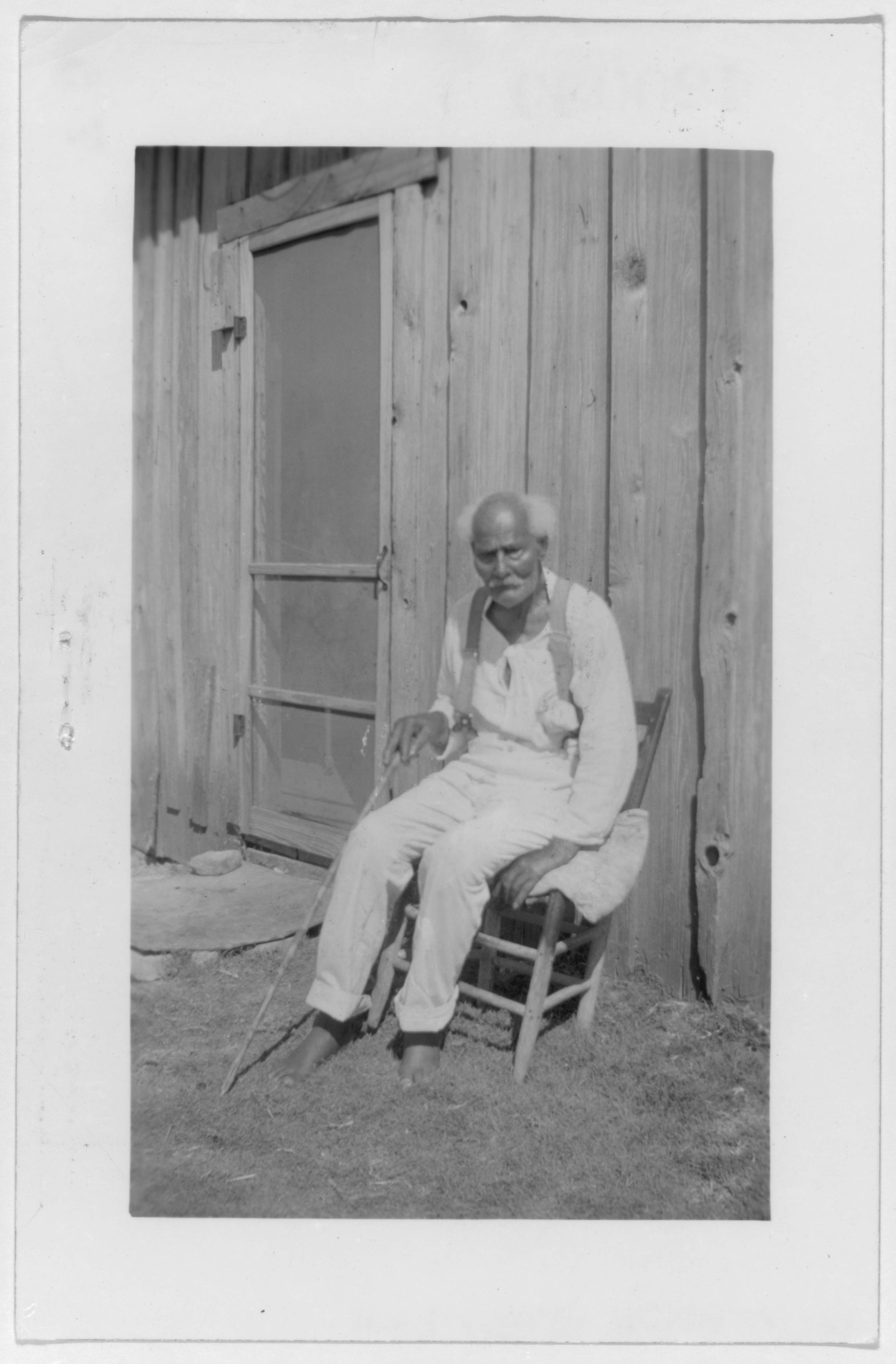

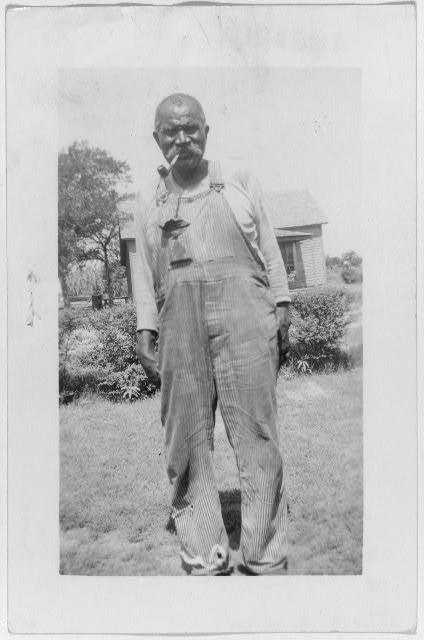

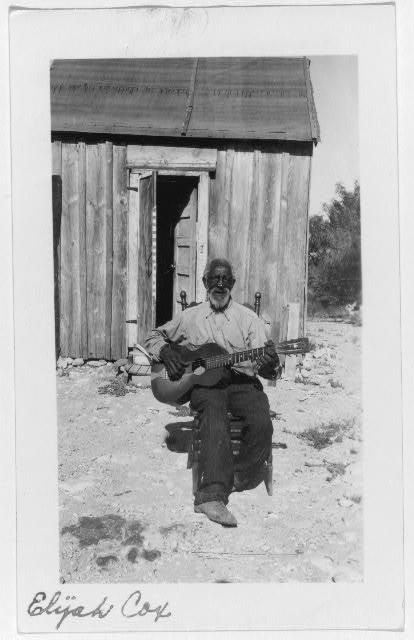

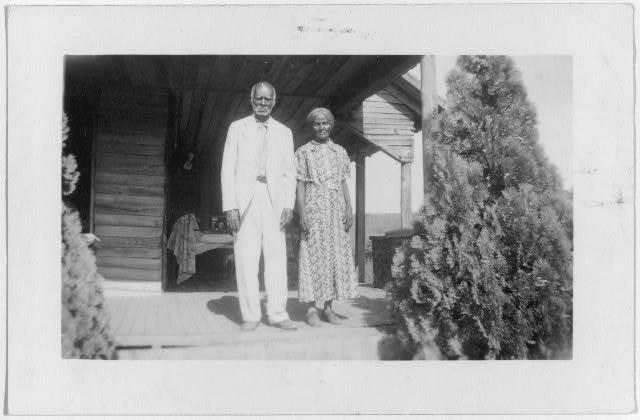

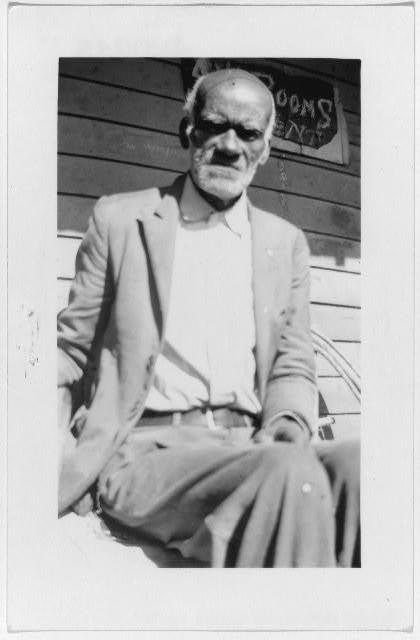

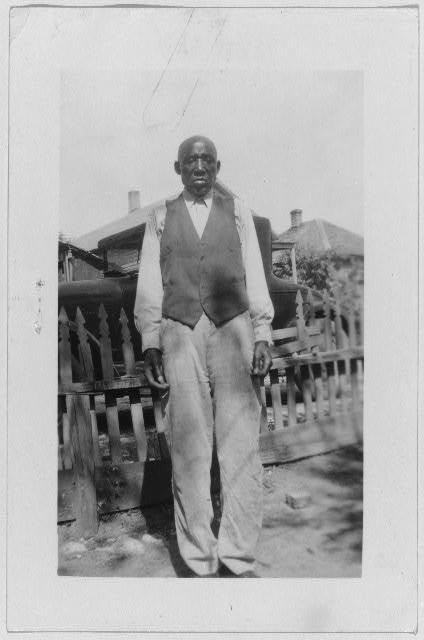

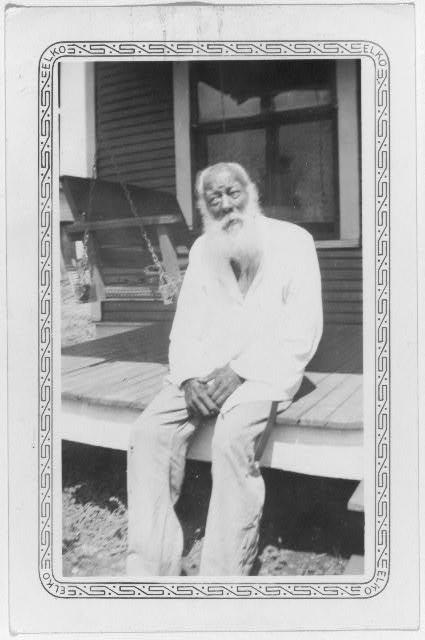

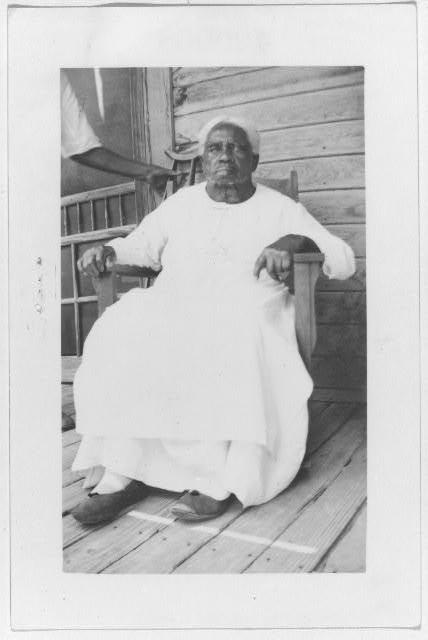

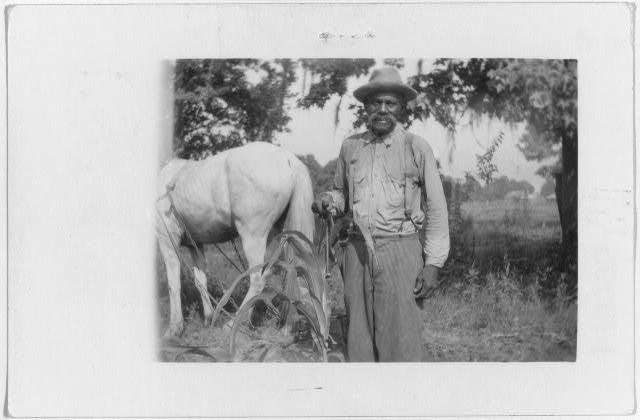

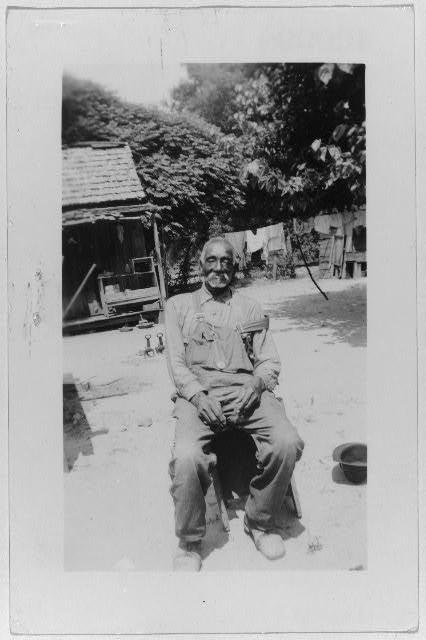

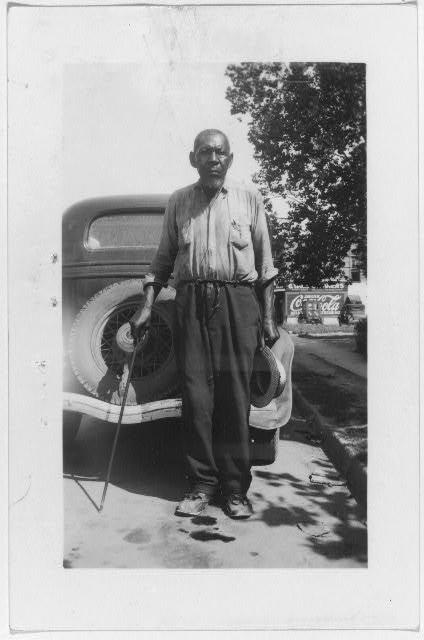

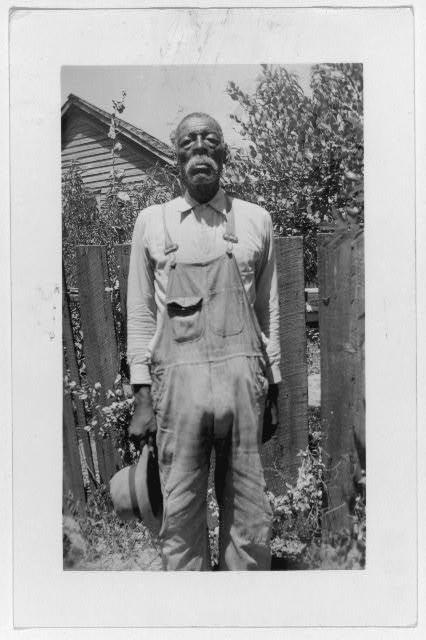

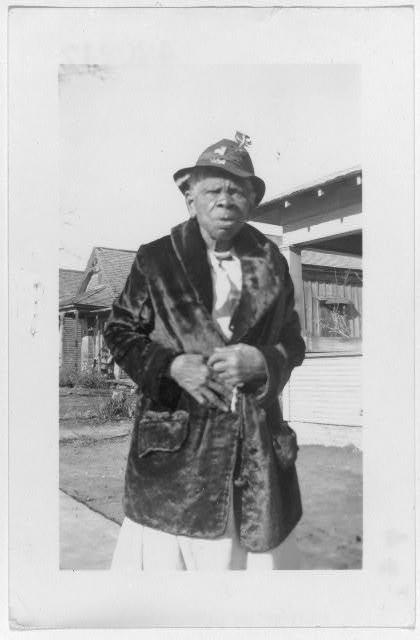

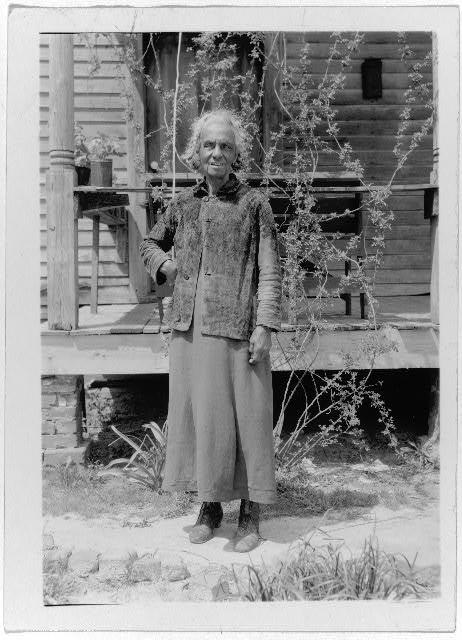

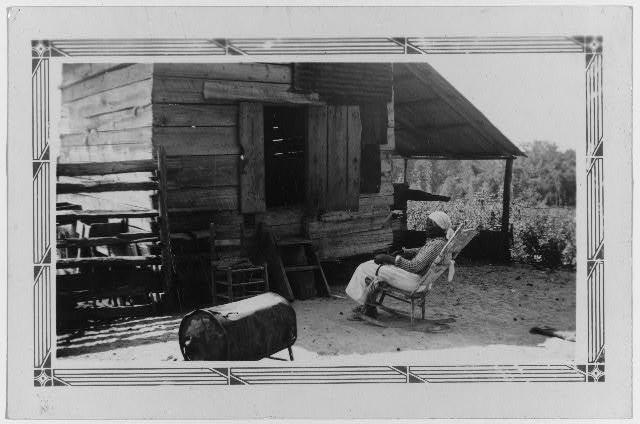

These are ‘Portraits of African American ex-slaves from the U.S. Works Progress Administration, Federal Writers Project slave narratives collections’ at the US Library of Congress. The collection is also labelled: ‘Born in slavery, slave narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938.’ The collection features photographs of emancipated black slaves and their stories.

The Government hired unemployed writers to travel the USA recording stories.

The Federal Writers’ Project was created in 1935 as part of the United States Work Progress Administration to provide employment for historians, teachers, writers, librarians, and other white-collar workers. Originally, the purpose of the project was to produce a series of sectional guide books under the name American Guide, focusing on the scenic, historical, cultural, and economic resources of the United States.

The pictures and stories below were published in 1941 as the seventeen-volume “Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves.”

The portraits are of men and women from locations in Texas, Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, and Rhode Island.

Why show them now?

On Jan. 31, 1865, slavery in the USA was abolished. At the second time of asking The House of Representatives passed the Thirteenth Amendment by a vote of 119 to 56.

Every face tells a story:

Interviewer: Pernella M. Anderson

Person interviewed: Rachel Hankins

El Dorado, Arkansas

Age: 88

“I was born in Alabama. My old mistress and master told me that I was born in 1850. Get that good—1850! That makes me about 88 but I can’t member the day and month. I was a girl about twelve or fourteen years old when the old darkies was set free. My old mistress and master did not call us niggers; they called us darkies. I can’t recollect much about slavery and I can recollect lots too at times. My mind goes and comes. I tell you children you all is living a white life nowdays. When I was coming up I was sold to a family in Alabama by the name of Columbus. They was poor people and they did not own but a few slaves and it was a large family of them and that made us have to work hard. We lived down in the field in a long house. We ladies and girls lived in a log cabin together. Our cabin had a stove room made on the back and it was made of clay and grass with a hearth made in it and we cooked on the hearth. We got our food from old mistress’s and master’s house. We raised plenty of grub such as peas, greens, potatoes. But our potatoes wasn’t like the potatoes is now. They was white and when you eat them they would choke you, especially if they was cold. And sorghum molasses was the only kind there was. I don’t know where all these different kinds of molasses come from.

“They issued our grub out to us to cook. They had cows and we got milk sometimes but no butter. They had chickens and eggs but we did not. We raised cotton, sold part and kept enough to make our clothes out of. Raised corn. And there wasn’t no grist mills then so we had a pounding rock to pound the corn on and we pound and pound until we got the corn fine enough to make meal, then we separated the husk from the meal and parched the husk real brown and we used it for coffee. We used brown sugar from sorghum molasses. We spun all our thread and wove it into cloth with a hand loom. The reason we called that cloth home-spun is because it was spun at home. Splitting rails and making rail fences was all the go. Wasn’t no wire fences. Nothing but rail fences. Bushing and clearing was our winter jobs. You see how rough my hands is? Lord have mercy! child, I have worked in my life.

“Master Columbus would call us niggers up on Sunday evening and read the Bible to us and tell us how to do and he taught us one song to sing and it was this ‘Keep Your Lamp Trimmed and Burning’ and he’d have us to sing it every Sunday evening and he told us that that song meant to do good and let each other see our good. When it rained we did not have meeting but when it was dry we always had meeting.

“I never went to school a day in my life. I learned to count money after I was grown and married.

“My feet never saw a shoe until I was fourteen. I went barefooted in ice and snow. They was tough. I did not feel the cold. I never had a cold when I was young. If we had ep-p-zu-dit we used different things to make tea out of, such as shucks, cow chips, hog hoofs, cow hoofs. Ep-p-zu-dit then is what people call flu now.

“When war broke out I was a girl just so big. All I can recollect is seeing the soldiers march and I recollect them having on blue and gray jackets. Some would ride and some would walk and when they all got lined up that was a pretty sight. They would keep step with the music. The Southern soldiers’ song was ‘Look Away Down in Dixie’ and the Northern soldiers’ song was ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy.’ So one day after coming in from the field old master called his slaves and told us we was free and told us we could go or stay. If we stayed he would pay us to work. We did not have nothing to go on so we stayed and he paid us. Every 19th of June he would let us clean off a place and fix a platform and have dancing and eating out there in the field. The 19th of June 1865 is the day we thought we was freed but they tell me now that we was freed in January 1865 but we did not know it until June 19, 1865. Never got a beating the whole time I was a slave.

“I came to north Arkansas forty years ago and I been in Union County a short while. My name is Rachel Hankins.”

Name of Interviewer: Irene Robertson

Subject: Spells—Voodoo—

Story—Information (If not enough space on this page add page)

I asked her if she believed anyone could harm her and she said not not unless they could get her to eat or drink something. Then they might. She said a Gypsy was feeling her and slipped a dollar and a quarter tied up in her handkerchief from her and she never did know when or how she got it. Said she never believed their tales or had her fortune told. She didn’t believe anyone could put anything under the door and because you walked over it you would get a “spell”. She said some people did. She didn’t know what they put under the doors. She never was conjured that she knew of and she doesn’t believe in it. Said she had to work too hard to tell tales to her children but she used to sing. She can’t remember the songs she sang. She can’t read or write.

The old woman is blind and gray, wears a cap. Her Mistress was Mrs. Mary and her Master was Mr. Hardy Sellers in Chesterfield County, South Carolina. Her husband died and left her with six children. Her brother came with a lot of other fellows to Arkansas. “Everybody was coming either here or to Texas”. Mr. David Gates at DeValls Bluff sent her a ticket to come to his farm. Her brother was working for Mr. Gates Wattensaw plantation and that is where she has been till a few years ago she moved to Hazen and lives with her son and his wife. She remembered when the Civil War soldiers took all their food, mules and hitched Mrs. Sellers driving horses to the surry and drove off. Her Mistress cried and cried. She said she had a hard time after she left Mr. and Mrs. Sellers, they was sure good to them and always had more than she had ever had since. She wanted to go back to South Carolina to see the ones she left but never did have the money. Said they lived on Mr. Dick Small’s place and he was so good to her and her children but he is dead too now.

This information given by: Hannah Hancock

Place of Residence: Hazen, Arkansas

Occupation: Work in the cotton field—Cook and wash.

Age: 90

She is blind. She gets $8.00 pension, she is proud to tell.

Interviewer: Miss Irene Robertson

Person interviewed: Lawrence Hampton

R.F.D., Forrest City, Arkansas

Age: 78

“I was born in Orangeburg, South Carolina. My parents’ names was Drucilla and Peter Hampton. She was the mother of twelve children. They both b’long to John D. Kidd and Texas Kidd. To my knowing they had no children. They was old to me being a child but I don’t reckon they be old folks. They had a plantation, some hilly and some bottom land. He had two or three hundred slaves. He was a good, good man. He was a good master. He had some white overseers and some black overseers. Grandpa Peter was one of his overseers. He was proud of his slaves. He was a proud man.

“We all had preaching clothes to wear. He had his slaves be somebody when they got out of the field. They went in washing at the fish pond, duck pond too. It was clear and sandy bottom. Wouldn’t be muddy when a lot of them got through washing (bathing). They was black but they didn’t stink sweaty. They wore starched clean ironed clothes. They cooked wheat flour and made clothes. When the War come on their clothes was ironed and clean but the wheat was scarce and the clothes got flimsy. John D. Kidd was loved by black and white. He was a good man. Grandpa George had a son sold over close to Memphis. They had twelve children last letter mama had from them. I’ve never seen any one of them.

“Grandpa Peter was a overseer. After he was made overseer he was paid. That was a honor for being good all his life. When freedom come on he had ten thousand dollars. He was pure African, black as ace of spades. He give papa and the other four boys five hundred dollars a piece to start them farms. Papa died when he was sixty-five and grandma was about a hundred. Mama was seventy-five when she died. Grandpa was eighty-five when he died. They didn’t know exactly but that was about their ages. It was a pretty big honor to be a carriage man. They had young men hostlers and blacksmiths.

“Freedom—The boys all stayed around and girls too. They bought places about. They never would charge John D. Kidd for work. They let the girls cook, milk, and set the fowls, long as the old couple lived. They never took no pay. They go in gangs and chop out his crop and big picnic dinners all they ever took from him. We all loved that old man.

“They done some whooping on the place but it was a shame. They got over it and went on dressed up soon as the task was done. Never heard much said about it. I never seen nobody whooped.

“My own folks whooped me. We was free then.

Interviewer: Miss Irene Robertson

Person interviewed: Linley Hadley

Madison, Arkansas

Age: 77

“I was born the very day the Civil War started, April 12, 1861. I was born in Monroe County close to Aberdeen, Mississippi. My papa was named Dave Collins. He was born far back as 1832. He was a carriage driver.

“Mama was born same year as papa. She was a field hand and a cook. She could plough good as any man. She was a guinea woman. She weighed ninety-five pounds. She had fourteen children. She did that. Had six or seven after freedom. She had one slave husband. Her owners was old Master Wylie Collins and Mistress Jane. We come ’way from their place in 1866.

“I can recollect old Master Collins calling up all the niggers to his house. He told them they was free. There was a crowd of them, all mixes. Why all this took place now I don’t know. Most of the niggers took what all they have on their heads and walked off. He told mama to move up in the loom house, if she go off he would kill her. We moved to the loom house till in 1866.

Interviewer: Miss Irene Robertson

Persons interviewed: William and Charlotte Guess

West Memphis, Arkansas

Ages: 68 and 66

William Guess

“I was born in Monroe County, Arkansas. Father come from Dallas, Texas when a young man before he married. Him and two other men was shipped in a box to Indian Bay. I’ve heard him and Ike Jimmerson laugh how they got bumped and bruised, hungry and thirsty in the box. I forgot the name of the other man in the box. They was sent on a boat and changed boats where they got tumbled up so bad. It was in slavery or war times one. White folks nailed them up and opened them up too I think. Father was born in Dallas, Texas. Mother was a small woman and come from Tennessee. Billy Boyce in Monroe County owned her. That is the most I ever heard my folks tell about the Civil War.”

Charlotte Guess

“Mother was born in Dallas, Texas. She was born into slavery. She was a field woman. She was sold there and brought to Mississippi at about the close of the Civil War. She was sold from her husband and two children. She never seen them. She farmed cotton and corn in Texas. Her husband whooped her, so she was glad to be sold. She married after the surrender to another man in Mississippi. No, he didn’t beat her. They had disputes. She was the mother of ten children. She lived to be 82 years old. She went from Arkansas back to Mississippi to die.”

INTERVIEWER’S NOTE

It would be interesting if I could find out more about why the Negroes were sent in the box. He seemed not to know all about it. This Negro man when young was a light mulatto. He is light for his age. He looks and acts white. Has a spot on one eye.

Interviewer: Samuel S. Taylor

Person interviewed: Wesley Graves

817 Hickory Street, North Little Rock, Arkansas

Age: 70

[Father Taught Night School]

“My father’s white folks were named Tal Graves. My mother was a McAdoo. Her white folks were McAdoos. Some of them are over the river now. He’s a great jewelryman now.

“I was born in Trenton, Tennessee. My father was born ’round in Humboldt, Tennessee. My mother was born in Paris, Tennessee and moved out in the country near Humboldt. He met my mother out there and married her just a little bit before the War. He was a slave and she was too.

“He didn’t go to the War; he went to the woods. He got to chasing ’round. His young mistress married. She married a Graves. That was the name we was freed under. She was a Shane.

“She educated my father. When she come from school, she would teach him and just carry him right on through the course that way. That was a good while before the War. Her father gave him to her when she married Graves. He was a little boy and she kept him and educated him. Graves ran a farm. I don’t know just what my father did when he was little. He was raised up as a house boy. Very little he ever done in the field. I don’t know what he did after he grew up and before freedom came. After peace was declared, he taught in night school. He preached too. His first farming was done a little after he come out here. I was about seven years old then. That was in the year 1873.

“My mother’s full name was Adeline McAdoo. Before freedom she did housework. She was a kind a pet with the white folks. She didn’t do much farming. My mother and father had six children—five boys and one girl. All born after freedom. There were three ahead of me. The oldest was born before the War, not afterward.

“In my country where I was raised the Negroes weren’t freed until 1865. My uncle, Jim Shane—that is the only name I ever knew him by—, he ran away and come to this country and made money enough to come back and buy his freedom. Just about time he got himself paid for, the War closed and he would have been freed anyway. The money wouldn’t have done him no good anyhow because it was all Confederate money, and when the War closed, that wasn’t no good.

“My father ran away when the War broke out. His master wanted to carry him to the army with him and he run off and stayed in the woods three years. He stayed until his little mistress wrote him a letter and told him she would set him free if he would come home. He stayed out till the War closed. He wouldn’t take no chances on it.

“The pateroles made my father do everything but quit. They got him about teaching night school. That was after slavery, but the pateroles still got after you. They didn’t want him teaching the Negroes right after the War. He had opened a night school, and he was doing well. They just kept him in the woods then.”

Ku Klux

“There was a bunch of Ku Klux that a colored man led. He was a fellow by the name of Fount Howard. They would come to his house and he would call himself showing them how to catch old people he didn’t like. He told them how to catch my old man. I have heard my mother tell about it time and time again. The funny part of it was there was a cornfield right back of the kitchen. Just about dusk dark, he got up and taken a big old horse pistol and shot out of it, and when he fired the last shot out of it, a white man said, ‘Bring that gun here.’ Believe me he cut a road through that field right now.

“They stayed ’round for a little while and tried to bully his people. But the old lady stood up to them, so they finally carried her and her children in the house and told her to tell him to come on back they wouldn’t hurt him. And they didn’t bother him no more.

“My mother’s master told my mother that she was free. He called all the slaves in and told them they were free as he was. I don’t think he give them anything when they were freed. He was a kind a poor fellow. Didn’t have but six or seven slaves. He offered to let them stay and make crops. My father had a better job than that. Did you ever know Bishop Lane out in Tennessee? My father and he were ordained at the same time in the some C. M. E. Church. Then he moved to Kentucky and joined the A. M. E. Church. My father died in 1875 and my mother in 1906.

“I have been married forty-seven years. I married on the twenty-sixth day of December in 1889. I heard my mother and father say that they married in slavery time and they just jumped over a broom. I don’t belong to no church. I am off on a pension. I got a good job doin’ nothing. My pension is paid by the Railroad.

“I put up forty-four years as a brakeman and five years on ditching trains before I went to braking. My old road master put me on the braking. A fellow got his fingers cut off and they turned his keys over to me and put me to braking and I went there and stayed.

“I have two children. Both of them are living—a girl and a boy. I have had a big bunch of young people ’round me ever since I married. Raised a couple of nephews. Then my two. All of them married. That is my daughter’s oldest child right there. (He pointed to a pretty brownskin girl—ed.)

“My father died when I was eight, and I was away from home railroading most of the time and didn’t hear much about old times from my mother. So that’s all I know.

“I have lived right here on this spot for forty-three years. About 1893 I bought this place and have lived here ever since. This was just a big woods and weed patch then. There weren’t more than about six houses out here this side of the Rock Island Railroad.

“I commenced voting in 1889. Cast my first ballot then. I never had any trouble about it.”

Interviewer: Mrs. Bernice Bowden

Person interviewed: Marthala Grant

2203 E. Barraque, Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Age: 77

“All I can remember is some men throwin’ us up in the air and ketchin’ us, me and my baby brother. Like to scared me to death. They had on funny clothes. Me and my brother was out in the yard playin’. They just grabbed us up and throwed us up and ketched us.

“My mother would tell us bout the war. She had on some old shoes—wooden shoes. Her white folks name was Hines. That was in North Carolina. I emigrated here when they was emigratin’ folks here. I was grown then.

“Durin’ the war I heered the shootin’ and the people clappin’ their hands.

“My mother said they was fightin’ to free the people but I didn’t know what freedom was. I member hearin’ em whoopin’ and hollerin’ when peace was ’clared and talkin’ bout it.

“Yes’m I went to school some—not much. I learned a right smart to read but not much writin’.

“We’d go up to the white folks house every Sunday evenin’ and old mistress would learn us our catechism. We’d have to comb our heads and clean up and go up every Sunday evenin’. She’d line us up and learn us our catechism.

“We stayed right on there after the war. They paid my mother. I picked cotton and nussed babies and washed dishes.

“I was married when I was twenty. Never been married but once and my husband been dead nigh bout twenty years.”

“When I come here this town wasn’t much—sure wasn’t much. Used to have old car pulled by mules and a colored man had that—old Wiley Jones. He’s dead now.

“I had eleven childen. All dead but five. My boy what’s up North went to that Spanish War. He stayed till peace was declared.

“After we come to Arkansas my husband voted every year and worked the county roads. I guess he voted Republican.

“I can’t tell you bout the younger generation. They so fast you can’t keep up with them. I really can’t tell you.”

Interviewer: Beulah Sherwood Hagg

Person interviewed: Mrs. Cora Gillam

1023 Arch Street, Little Rock, Arkansas

Age: 86

[Scratching Pacified Master.]

“I have never been entirely sure of my age. I have kept it since I was married and they called me fifteen. That was in ’66 or ’67. Anyhow, I’m about 86, and what difference does one year make, one way or another. I lived with master and mistress in Greenville, Mississippi. They didn’t have children and kept me in the house with them all the time. Master was always having a bad spell and take to his bed. It always made him sick to hear that freedom was coming closer. He just couldn’t stand to hear about that. I always remember the day he died. It was the fall of Vicksburg. When he took a spell, I had to stand by the bed and scratch his head for him, and fan him with the other hand. He said that scratching pacified him.

“No ma’am, oh no indeedy, my father was not a slave. Can’t you tell by me that he was white? My brother and one sister were free folks because their white father claimed them. Brother was in college in Cincinnati and sister was in Oberlin college. My father was Mr. McCarroll from Ohio. He came to Mississippi to be overseer on the plantation of the Warren family where my mother lived. My grandmother—on mother’s side, was full blood Cherokee. She came from North Carolina. In early days my mother and her brothers and sisters were stolen from their home in North Carolina and taken to Mississippi and sold for slaves. You know the Indians could follow trails better than other kind of folks, and she tracked her children down and stayed in the south. My mother was only part Negro; so was her brother, my uncle Tom. He seemed all Indian. You know, the Cherokees were peaceable Indians, until you got them mad. Then they was the fiercest fighters of any tribes.

“Wait a minute, lady. I want to tell you first why I didn’t get educated up north like my white brother and sister. Just about time for me to be born my papa went to see how they was getting along in school. He left my education money with mama. He sure did want all his children educated. I never saw my father. He died that trip. After awhile mama married a colored man name Lee. He took my school money and put me in the cotton patch. It was still during the war time when my white folks moved to Arkansas; it was Desha county where they settle. Now I want to tell you about my uncle Tom. Like I said, he was half Indian. But the Negro part didn’t show hardly any. There was something about uncle Tom that made both white and black be afraid of him. His master was young, like him. He was name Tom Johnson, too.

“You see, the Warrens, what own my mother, and the Johnsons, were all sort of one family. Mistress Warren and Mistress Johnson were sisters, and owned everything together. The Johnsons lived in Kentucky, but came to Arkansas to farm. Master Tom taught his slaves to read. They say uncle Tom was the best reader, white or black, for miles. That was what got him in trouble. Slaves was not allowed to read. They didn’t want them to know that freedom was coming. No ma’am! Any time a crowd of slaves gathered, overseers and bushwhackers come and chased them; broke up the crowd. That Indian in uncle Tom made him not scared of anybody. He had a newspaper with latest war news and gathered a crowd of slaves to read them when peace was coming. White men say it done to get uprising among slaves. A crowd of white gather and take uncle Tom to jail. Twenty of them say they would beat him, each man, till they so tired they can’t lay on one more lick. If he still alive, then they hang him. Wasn’t that awful? Hang a man just because he could read? They had him in jail overnight. His young master got wind of it, and went to save his man. The Indian in uncle Tom rose. Strength—big extra strength seemed to come to him. First man what opened that door, he leaped on him and laid him out. No white men could stand against him in that Indian fighting spirit. They was scared of him. He almost tore that jailhouse down, lady. Yes he did. His young master took him that night, but next day the white mob was after him and had him in jail. Then listen what happened. The Yankees took Helena, and opened up the jails. Everybody so scared they forgot all about hangings and things like that. Then uncle Tom join the Union army; was in the 54th Regiment, U. S. volunteers (colored) and went to Little Rock. My mama come up here. You see, so many white folks loaned their slaves to the cessioners (Cecessionists) to help build forts all over the state. Mama was needed to help cook. They was building forts to protect Little Rock. Steele was coming. The mistress was kind; she took care of me and my sister while mama was gone.

“It was while she was in Little Rock that mama married Lee. After peace they went back to Helena and stayed two years with old mistress. She let them have the use of the farm tools and mules; she put up the cotton and seed corn and food for us. She told us we could work on shares, half and half. You see, ma’am, when slaves got free, they didn’t have nothing but their two hands to start out with. I never heard of any master giving a slave money or land. Most went back to farming on shares. For many years all they got was their food. Some white folks was so mean. I know what they told us every time when crops would be put by. They said ‘Why didn’t you work harder? Look. When the seed is paid for, and all your food and everything, what food you had just squares the account.’ Then they take all the cotton we raise, all the hogs, corn, everything. We was just about where we was in slave days.

“When we see we never going to make anything share cropping, mother and I went picking. Yes ma’am, they paid pretty good; got $1.50 a hundred. So we saved enough to take us to Little Rock. Went on a boat, I remember, and it took a whole week to make the trip. Just think of that. A whole week between here and Helena. I was married by then. Gillam was a blacksmith by trade and had a good business. But in a little while he got into politics in Little Rock. Yes, lady. If you would look over the old records you would see where he was made the keeper of the jail. I don’t know how many times he was elected to city council. He was the only colored coroner Pulaski county ever had. He was in the legislature, too. I used to dress up and go out to hear him make speeches. Wait a minute and I will get my scrap book and show you all the things I cut from the papers printed about him in those days….

“Even after the colored folks got put out of public office, they still kept my husband for a policeman. It was during those days he bought this home. Sixty-seven years we been living right in this place—I guess—when did you say the war had its wind up? It was the only house in a big forest. All my nine children was born right in this house. No ma’am, I never have worked since I came here. My husband always made a good living. I had all I could do caring for those nine children. When the Democrats came in power, of course all colored men were let out of office. Then my husband went back to his blacksmith trade. He was always interested in breeding fine horses. Kept two fine stallions; one was named ‘Judge Hill’, the other ‘Pinchback’. White folks from Kentucky, even, used to come here to buy his colts. Race people in Texas took our colts as fast as they got born. Only recently we heard that stock from our stable was among the best in Texas.

“The Ku Kluxers never bothered us in the least. I think they worked mostly out in the country. We used to hear terrible tales of how they whipped and killed both white and black, for no reason at all. Everybody was afraid of them and scared to go out after dark. They were a strong organization, and secret. I’ll tell you, lady, if the rough element from the north had stayed out of the south the trouble of reconstruction would not happened. Yes ma’am, that’s right. You see, after great disasters like fires and earthquakes and such, always reckless criminal class people come in its wake to rob and pillage. It was like that in the war days. It was that bad element of the north what made the trouble. They tried to excite (incite) the colored against their white friends. The white folks was still kind to them what had been their slaves. They would have helped them get started. I know that. I always say that if the south could of been left to adjust itself, both white and colored would been better off.

“Now about this voting business. I guess you don’t find any colored folks what think they get a fair deal. I don’t, either. I don’t think it is right that any tax payer should be deprived of the right to vote. Why, lady, even my children that pay poll tax can’t vote. One of my daughters is a teacher in the public school. She tells me they send out notices that if teachers don’t pay a poll tax they may lose their place. But still they can’t use it and vote in the primary. My husband always believed in using your voting privilege. He has been dead over 30 years. He had been appointed on the Grand Jury; had bought a new suit of clothes for that. He died on the day he was to go, so we used his new suit to bury him in. I have been getting his soldier’s pension ever since. Yes ma’am, I have not had it hard like lots of ex-slaves.

“Before you go I’d like you to look at the bedspread I knit last year. My daughters was trying to learn to knit. This craze for knitting has got everybody, it looks like. I heard them fussing about they could not cast on the stitches. ‘For land’s sakes,’ I said, ‘hand me them needles.’ So I fussed around a little, and it all came back. What’s funny about it is, I had not knitted a stitch since I was about ten. Old mistress used to make me knit socks for the soldiers. I remember I knit ten pair out of coarse yarn, while she was doing a couple for the officer out of fine wool and silk mixed. I used to knit pulse warmers, and ‘half-handers’,—I bet you don’t know what they was. Yes, that’s right; gloves without any fingers, ’cepting a thumb and it didn’t have any end. I could even knit on four needles when I was little. We used to make our needles out of bones, wire, smooth, straight sticks,—anything that would slip the yarn. Well, let me get back to this spread. In a few minutes it all came back. I began knitting washrags. Got faster and faster. Didn’t need to look at the stitches. The girls are so scared something will happen to me, they won’t let me do any work. Now I had found something I could do. When they saw how fast I work, they say: ‘Mother, why don’t you make something worth while? Why make so many washrags?’ So I started the bedspread. I guess it took me six months, at odd times. I got it done in time to take to Ft. Worth to the big exhibit of the National Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. My daughter was the national president that year. If you’ll believe it, this spread took first prize. Look, here’s the blue ribbon pinned on yet. What they thought was so wonderful was that I knit every stitch of it without glasses. But that is not so funny, because I have never worn glasses in my life. I guess that is some more of my Indian blood telling.

“Sometimes I have to laugh at some of these young people. I call them young because I knew them when they were babies. But they are already all broken down old men and women. I still feel young inside. I feel that I have had a good life.”

Interviewer: Miss Irene Robertson

Person interviewed: Jennie Wormly Gibson

Biscoe, Arkansas

Age: 49

“Gran’ma was Phoebe West. Mama was Jennie West. Mama was a little girl when the Civil War come on. She told how scared her uncle was. He didn’t want to go to war. When they would be coming if he know it or get glimpse of the Yankee soldiers, he’d pick up my mama. She was a baby. He’d run for a quarter of a mile to a great big tree down in the field way back of the place off the road. He never had to go to war. Ma said she was little but she was scared at the sight of them clothes they wore. Mama’s and grandma’s owners lived at Vicksburg a lot of the time but where that was at Washington County, Mississippi. They had lots of slaves.

“Grandma was a midwife and doctored all the babies on the place. She said they had a big room where they was and a old woman kept them. They et milk for breakfast and buttermilk and clabber for supper. They always had bread. For dinner they had meat boiled and one other thing like cabbage, and the children got the pot-liquor. It was brought in a cart and poured in wooden troughs. They had gourds to dip it out with. They had gourds to drink their cool spring water with.

“Daylight would find the hands in the field at work. Grandma said they had meat and bread and coffee till the war come on. They had to have a regular meal to work on in the morning.

“Grandma said their something to eat got mighty slim in war times and kept getting slimmer and slimmer. They had plenty sorghum all the time. Them troughs was hewed out of a log and was washed and hung in the sun till next mealtime. They cooked in iron pots and skillets on the fire. Grandma worked where they put her but her main trade was seeing after the sick on that place.

“They had a fiddler on the place and had big dances now and then.

“This young generation won’t be advised no way you can fix it. I don’t know what in the world the folks is looking about. The folks ain’t good as they used to be. They shoots craps and drinks and does low-down things all the time. I ain’t got no time with the young generation. Times gone to pieces pretty bad if you axing me.”

Interviewer: Samuel S. Taylor

Person interviewed: Will Glass

715 W. Eighth Street, Little Rock, Arkansas

Age: 50

Occupation: All phases of paving work

[Bit Dog’s Foot Off]

“My grandfather was named Joe Glass. His master was named Glass. I forget the first name. My grandfather on my mother’s side was named Smith. His old master was named Smith. The grandfather Joe was born in Alabama. Grandfather Smith was born in North Carolina.”

Whippings

“There were good masters and mean masters. Both of my old grandfathers had good masters. I had an uncle, Anderson Fields, who had a tough master. He was so tough that Uncle Anderson had to run away. They’d whip him and do around, and he would run away. Then they would get the dogs after him and they would run him until he would climb a tree to get away from them. They would come and surround the tree and make him come down and they would whip him till the blood ran, and sometimes they would make the dogs bite him and he couldn’t do nothing about it. One time he bit a dog’s foot off. They asked him why he did that and he said the dog bit him and he bit him back. They whipped him again. They would take him home at night and put what they called the ball and chain on him and some of the others they called unruly to keep them from running away.

“They didn’t whip my grandfathers. Just one time they whipped Grandfather Joe. That was because he wouldn’t give his consent for them to whip his wife. He wouldn’t stand for it and they strapped him. He told them to strap him and leave her be. He was a good worker and they didn’t want to kill him, so they strapped him and let her be like he said.”

Picnics

“Both of my grandfathers said their masters used to give picnics. They would have a certain day and they would give them all a good time and let them enjoy themselves. They would kill a cow or some kids and hogs and have a barbecue. They kept that up after freedom. Every nineteenth of June, they would throw a big picnic until I got big enough to see and know for myself. But their masters gave them theirs in slavery times. They gave it to them once a year and it was on the nineteenth of June then.

“Grandfather Joe said when he wanted to marry Jennie, she was under her old master, the man that Anderson worked under. Old man Glass found that Grandfather Joe was slipping off to old man Field’s to see Grandma Jennie, who was on Field’s place, and old man Fields went over and told Glass that he would either have to sell Glass to him or buy Jennie from him. Old man Glass bought Jennie and Grandfather Joe got her.

“After old man Glass bought Jennie, he held up a broom and they would have to jump over it backwards and then old man Glass pronounced them man and wife.

“Grandfather Joe died when I was a boy ten years old. Grandfather Smith died in 1921. He was eighty years old when he died. Grandfather Joe was seventy-two years old when he died. He died somewhere along in 1898.”

Whitecaps

“I heard them speak of the Ku Klux often. But they didn’t call them Ku Klux; they called them whitecaps. The whitecaps used to go around at night and get hold of colored people that had been living disorderly and carry them out and whip them. I never heard them say that they whipped anybody for voting. If they did, it wasn’t done in our neighborhood.”

Worship

“Uncle Anderson said that old man Fields didn’t allow them to sing and pray and hold meetings, and they had to slip off and slip aside and hide around to pray. They knew what to do. People used to stick their heads under washpots to sing and pray. Some of them went out into the brush arbors where they could pray and shout without being disturbed.

“Grandfather Joe and Grandfather Smith both said that they had seen slaves have that trouble. Of course, it never happened on the plantations where they were brought up. Uncle Anderson said that they would sometimes go off and get under the washpot and sing and pray the best they could. When they prayed under the pot, they would make a little hole and set the pot over it. Then they would stick their heads under the pot and say and sing what they wanted.”

Slave Sales

“Grandfather Joe and Grandfather Smith used to say that when a child was born if it was a child that was fine blooded they would put it on the block and sell it away from its parents while it was little. Both of my grandfathers were sold away from their parents when they were small kids. They never knew who their parents were.

“When my oldest auntie was born, my mother said she was sold about two years before freedom. Aunt Emma was only two years old then when she was sold. Mother never met her until she was married and had a family. They would sell the children slaves of that sort at auction, and let them go to the highest bidder.”

Opinions

“My grandfather brought me up strictly. I don’t know what they thought about the young people of their day, but I know what I think. I will tell you. At first I searched myself. Kids in the time I came along had to go by a certain rule. They had to go by it.

“We don’t see to our children doing right as our parents saw to our doing. It would be good if we could get ourselves together and bring these young people back where they belong. What ruined the young folks is our lack of discipline. We send them to school but that is all, and that is not enough. We ought to take it on ourselves to see that they are learning as they ought to learn and what they ought to learn.

“I belong to Bethel A. M. E. Church. I married about 1919, November 16. I have just one kid and two grand kids.”

1937

Interviewer: Miss Irene Robertson

Person interviewed: Charlie Gadson

Brinkley, Arkansas

Age: 67

“I was born in Barnwell County, South Carolina. My parents’ name was Jane Gadson, Aaron Gadson. My mother master was Mr. Owens. That is all I ever knowed bout him. My father’s master was Rivers and Harley Gadson.

“They said they was to get something but they moved on. At the ending of that war the President of the United States got killed. They wouldn’t knowed they was free if they hadn’t made some change. I don’t know what made them think they would get something at freedom less somebody told them they would.

“I work at the oil mill and at sawmilling. I been farmin’ mostly since I been here. I got kidney trouble and rheumatism till I ain’t no count. I own a house and lot in Brinkley.”

Interviewer: Thomas Elmore Lucy

Person interviewed: George Govan

Russellville, Arkansas

Age: 52

“George Govan is my name, and I was born in Conway County somewheres in December 1886—I guess it was about de seventeenth of December. We lived there till 1911, when I come to Pope County. Both my parents was slaves on de plantation of a Mr. Govan near Charleston, South Carolina. Dat’s where we got our name. Folks come to Arkansas after dey was freed. No sir, I ain’t edicated—never had de chance. Parents been dead a good many years.

“Yas suh, my folks used to talk a heap and tell me lots of tales of slavery days, and how de patrollers used to whip em when dey wanted to go some place and didn’t have de demit to go. Yas suh, dey had to have a demit to go any place outside work hours. Dey whipped my mother and father both sometimes, and dey sure was afraid of dem patrollers. Used to say, ‘If you don’t watch out de patrollers’ll git you.’ Dey’d catch de slaves and tie em up to a tree or a pos’ and whip em wid buggy whips and rawhides.

“Some of de slaves was promised land and other things when dey was freed, and some wasn’t promised nothin’. Some got land and a span of mules, and some didn’t get nothin’. No suh, my daddy didn’t farm none at first after he was freed because he didn’t have no money to buy land, but he done odd jobs here and there till he come to Arkansas seven or eight years after the War.

“Yes, I owns my own home; been livin’ in it for ten years, since I’ve been workin’ as janitor at dis Central Presbyterian Church. I belongs to de Missionary Baptis’ Church, but my parents were both Methodists.

“Sure did have lots of good songs in de old days, like ‘Old Ship of Zion’ and ‘On Jordan’s Stormy Banks.’ Used to have one that begins ‘Those that ’fuse to sing never knew my God.’ It was a purty piece; and then there was another one about a ‘Rough, rocky road.’

“De young people today has much better opportunities than when I was a child, and much better than dey had in slavery days, because dar ain’t no patrollers to whip em. Most of em dese days has purty good behavior, and I think dey’re better than in de old days.

“I has always voted regularly since I come of age—votes de Republican ticket. Can’t read but a little, but I never had any trouble about votin’.”

NOTE: George Govan is an intelligent Negro, fairly neat in his dress, very tall and erect in stature. Brogue quite noticeable, and occasional idioms that make his interview interesting and personal.

Interviewer: Samuel S. Taylor

Person interviewed: Dr. D. B. Gaines

1720 Izard Street, Little Rock, Arkansas

Age: 75

“I was born in 1863 and am now seventy-five years old. You see, therefore, that I know nothing experimentally and practically about slavery.

“I was born in South Carolina in Lawrence County, and my father moved away from the old place before I had any recollection. I remember nothing about it. My father said his master’s name was Matthew Hunter.

“I was named for my father’s master’s brother, Dr. Bluford Gaines. My name is Doctor Bluford Gaines. Of course, I am a doctor but my name is Doctor.

“My father’s family moved to Arkansas, in 1882. Settled near Morrilton, Arkansas. I myself come to Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1885, October eighth. Worked in the homes of white families for my board and entered Philander Smith College October 8, 1885. Continued to work with Judge Smith of the Arkansas Supreme Court until I graduated from Philander Smith College. After graduating I taught school and was elected Assistant Principal of the Little Rock Negro High School in 1891. Served three years. Accumulated sufficient money and went to Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tennessee. Graduated there in 1896. Practiced for five years in the city of Little Rock. Entered permanently upon the ministry in 1900. Was called to the Mount Pleasant Baptist Church where I have been pastoring for thirty-nine years the first Sunday in next May.

“The first real thing that made me switch from the medicine to the ministry was the deep call of the ministry gave me more interest in the Gospel than the profession of medicine furnished to me. In other words, I discovered that I was a real preacher and not a real doctor.

“Touching slavery, the white people to whom my parents belonged were tolerant and did not allow their slaves to be abused by patrollers and outsiders.

“My mother’s people, however, were sold from her in very early life and sent to Alabama. My mother’s maiden name was Harriet Smith. She came from South Carolina too. Her old master was a Smith. My mother and father lived on adjoining plantations and by permission of both overseers, my father was permitted to visit her and to marry her even before freedom. Out of regard for my father, his master bought my mother from her master. I think my father told me that the old master called them all together and announced that they were free at the close of the War. Right after freedom, the first year, he remained on the farm with the old master. After that he moved away to Greenville County, South Carolina, and settled on a farm, with the brother-in-law of his old master, a man named Squire Bennett. He didn’t go to war.

“There was an exodus of colored people from South Carolina beginning about 1880, largely due to the Ku Klux or Red Shirts. They created a reign of terror for colored people in that state. He joined the exodus in 1882 and came to Arkansas where from reports, the outlook seemed better for him and his family. He had no trouble with the Ku Klux in Arkansas. He maintained himself here by farming.”

Opinions

“It is my opinion that from a racial standpoint, the lines are being drawn tighter due to the advancement of the Negro people and to the increased prejudice of the dominant race. These lines will continue to tighten until they somehow under God are broken. We believe that the Christian church is slowly but surely creating a helpful sentiment that will in time prevail among all men.

“It appears from a governmental standpoint that the nation is doomed sooner or later to crash. Possibly a changed form of government is not far ahead. This is due to two reasons: (1) greed, avarice, and dishonesty on the part of public people; (2) race prejudice. We believe that the heads of the national government have a far vision. The policies had they been carried out in keeping with the mind of the President, would have worked wonders in behalf of humanity generally. But dishonesty and greed of those who had the carrying out of these policies has destroyed their good effect and the fine intentions of the President who created them. It looks clear that neither the Democratic nor the Republican party will ever become sufficiently morally righteous to establish and maintain a first-class humanitarian and unselfish government.

“It is my opinion that the younger generation is headed in the wrong direction both morally and spiritually. This applies to all races. And this fact must work to the undoing of the government that must soon fall into their hands, for no government can well exist founded upon graft, greed, and dishonesty. It seems that the younger group are more demoralized than the younger group were two generations ago. Thus the danger both to church and state. Unless the church can catch a firmer grip upon the younger group than it has, the outlook is indeed gloomy.

“We are so far away from the situation of trouble in Germany, that it is difficult to know what it is or should be. But one thing must be observed—that any wholesale persecution of a whole group of people must react upon the persecutors. There could no cause arise which would justify a governmental power to make a wholesale sweep of any great group of people that were weak and had no alternative. That government which settles its affairs by force and abuse shows more weakness than the weak people which it abuses.

“We need not think that we are through with the job when we kill the weaker man. No cause is sufficient for the destruction of seven hundred thousand people, and no persecutor is safe from the effects of his own persecution.”

Interviewer’s Comment

The house at 1720 Izard is the last house in what would otherwise be termed a “white” block. There appears to be no friction over the matter.

Note that if you were calling Dr. Gaines by his professional title and his first name at the same time, you would say Dr. Doctor Bluford Gaines. He has attained proficiency in three professions—teaching, medicine, and the ministry.

Dr. Gaines is poised in his bearing and has cultured tastes and surroundings—neat cottage, and simple but attractive furnishings.

He selects his ideas and words carefully, but dictates fluently. He knows what he wants to say, and what he omits is as significant as what he states.

He is the leader type—big of body, alert of mind, and dominant. It is said that he with two other men dominated Negro affairs in Arkansas for a considerable period of time in the past. He does not give the impression of weakness now.

Despite his education, contacts, and comparative affluence, however, his interview resembles the type in a number of respects—the type as I have found it.

Interviewer: Miss Irene Robertson

Person interviewed: Mary Gaines

Brinkley, Arkansas

Age: Born 1872

“I was born in Courtland, Alabama. Mother was twelve years old at the first of the surrender.

“Grandfather was a South Carolinian. Master Harris bought him, two more, his brothers and two sisters and his mother at one time. He was real African. Grandma on mother’s side was dark Indian. She had white hair nearly straight. I have some of it now. Mother was lighter. That is where I gets my light color.

“Master Harris sold mother and grandma. Mother said she was fat, tall strong looking girl. Master Harris let a Negro trader have grandma, mother and her three brothers. They left grandpa. Master Harris told the nigger traders not divide grandma from her children. He didn’t believe in that. He was letting them go from their father. That was enough sorrow for them to bear. That was in Alabama they was auctioned off. Master Harris lived in Georgia. The auctioneerer held mother’s arms up, turned her all around, made her kick, run, jump about to see how nimble and quick she was. He said this old woman can cook. She has been a good worker in the field. She’s a good cook. They sold her off cheap. Mother brought a big price. They caught on to that. The man nor woman wasn’t good to them. I forgot their names what bought them. The nigger traders run her three brothers on to Mississippi. The youngest one died in Mississippi. They never seen the other two or heard of them till after freedom. They went back to Georgia. All of them went back to their old home place.

“In Alabama at this new master’s home mother was nursing. Grandma and another old woman was the cooks. Mother went to their little house and told them real low she had the baby and a strange man in the house said, ‘Is that the one you goiner let me have?’ The man said, ‘Yes, he’s goiner leave in the morning b’fore times.’

“The new master come stand around to see when they went to sleep. That night he stood in the chimney corner. There was a little window; the moon throwed his shadow in the room. They said, ‘I sure do like my new master.’ Another said, ‘I sure do.’ The other one said, ‘This is the best place I ever been they so good to us.’ Then they sung a verse and prayed and got quiet. They heard him leave, seen his shadow go way. Heard his house door squeak when he shut his door. Then they got up easy and dressed, took all the clothes they had and slipped out. They walked nearly in a run all night and two more days. They couldn’t carry much but they had some meat and meal they took along. Their grub nearly give out when they come to some camps. Somebody told them, ‘This is Yankee camps.’ They give them something to eat. They worked there a while. One day they took a notion to look about and they hadn’t gone far ’fore Grandpa Harris grabbed grandma, then mama. They got to stay a while but the Yankees took them to town and Master Harris come got them and took them back. Their new master come too but he said his wife said bring the girl back but let that old woman go. Master Harris took them both back till freedom.

“When freedom come folks shout and knock down things so glad they was free. Grandpa come back. Master Harris said, ‘You can have land if you can get anything to work.’ Grandpa took his bounty he got when he left the army and bought a pair of mules. He had to pay rent the third year but till then he got what they called giving all that stayed a start.

“Grandma was Mariah and grandpa was Ned Harris. The two boys come back said the baby boy died at Selma, Alabama.

“Grandpa talked about the War when I was a child. He said he was in the Battle of Corinth, Mississippi. He said blood run shoe mouth deep in places. He didn’t see how he ever got out alive. Grandma and mama said they was glad to get away from the camps. They looked to be shot several times. Colored folks is peace loving by nature. They don’t love war. Grandpa said war was awful. My mother was named Lottie.

“One reason mother said she wanted to get away from their new master, he have a hole dug out with a hoe and put pregnant women on their stomach. The overseers beat their back with cowhide and them strapped down. She said ’cause they didn’t keep up work in the field or they didn’t want to work. She didn’t know why. They didn’t stay there very long. She didn’t want to go back there.

“My life has never been a hard one. I have always worked. Me and my husband run a cafe till he got drowned. Since then I have to work harder. I wash and iron, cook wherever some one comes for me. When I was a girl I was so much like mother—a fast, strong hand in the field, I always had work.

“Mother said, ‘Eat the beans and greens, pot-liquor and sweet milk, make you fat and lazy.’ That was what they put in the children’s wooden trays in slavery. They give the men and women meat and the children the broth and dumplings, plenty molasses. Sunday mother could cook at home in slavery if she’d ’tend to the baby too. All the hands on Harrises place et dinner with their family on Sunday. He was fair with his slaves.

“For the life of me I can’t see nothing wrong with the times. Only thing I see, you can’t get credit to run crops and folks all trying to shun farming. When I was on a farm I dearly loved it. It the place to raise young black and white both. Town and cars ruined the country.”

Interviewer’s Comment

Owns two houses in among white people.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.