“Education cannot prosper in any community unless…the best and most cultivated talents of that community can be brought in to exercise the way.”

– Emma Hart Willard

Emma Willard (February 23, 1787 – April 15, 1870) was a trailblazing American educator who founded the first school for women’s higher education in the United States, the Troy Female Seminary in Troy, New York. With the success of her school, Willard was able to travel across the country and abroad to promote education for women. The seminary was renamed the Emma Willard School in 1895 in her honour.

And to promote education Willard understood the power of visualising data, presenting facts and stories in the form of graphics and charts – much like WB Du Bois’s work with population and race, and how Florence Nightingale used visual data to save lives.

From the 1820s through to the US Civil War, Willard’s textbooks made data visual. She believed that we understand the visual before the verbal – eyes before ears – so information presented in text books, especially the dense text in history and geography books, needed to be reformed. And maps did a great job of presenting a clear and engaging view of all things.

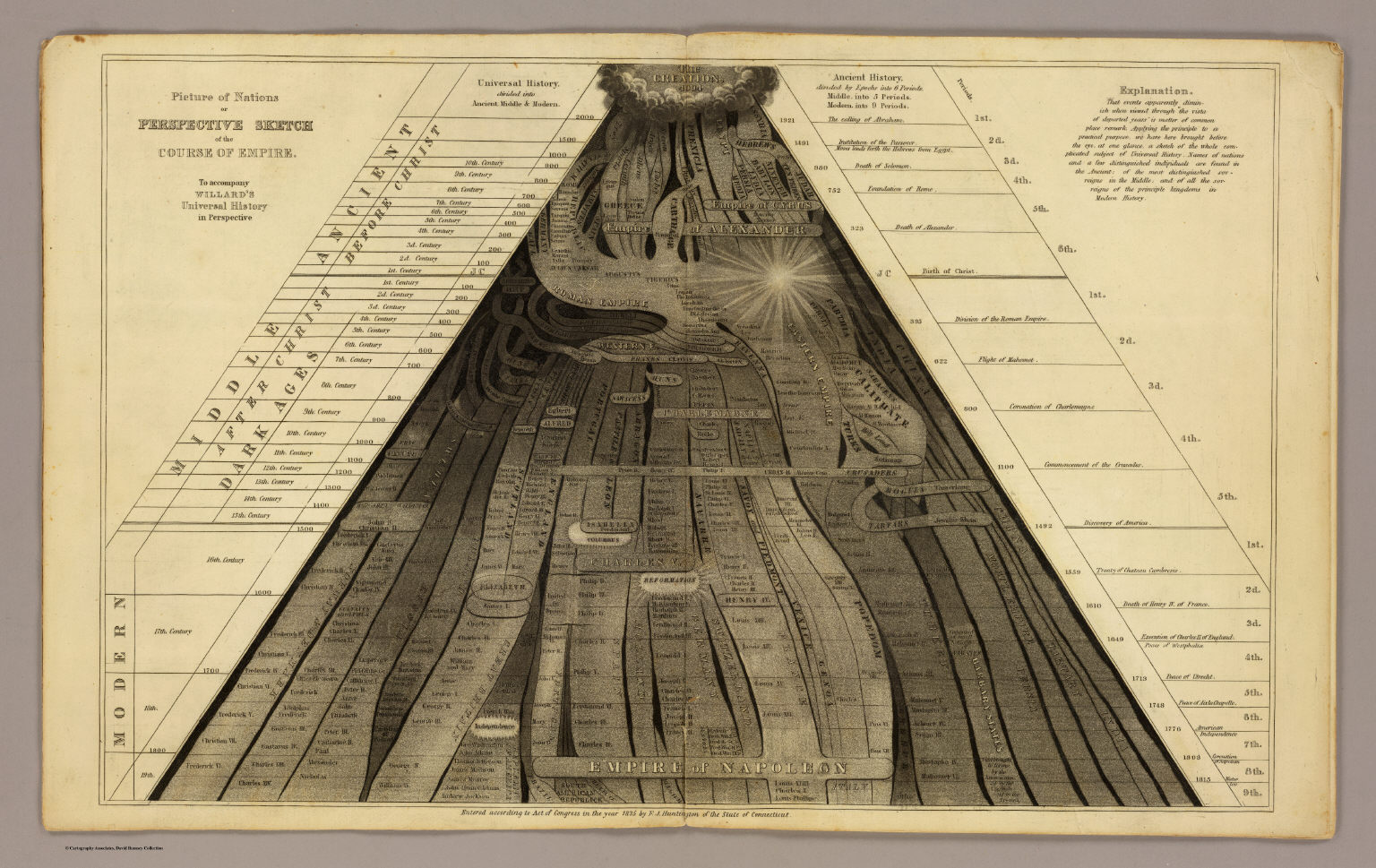

Emma Willard – Picture of the Nations

Willard published her first perspective time chart, Pictures of Nations or Perspective Sketch of the Course of Empire, in the Atlas to Accompany a System of Universal History (1836). She explained her vision:

Mere straight lines not wrought into a picture, and presenting no form of comeliness to the eye, are unattractive. The young (and the old too) do not feel any wish to look at them, and thus they carry away no distinct impression. They are like a succession of monotonous sounds, which no one remembers; while the arrangement of sounds in tunes, or lines in pictures, are attended to with pleasure, and easily remembered.

More cartography and books followed. Willard cowrote The Woodbridge and Willard Geographies and Atlases (1823) with American geographer William Channing Woodbridge. She co-authored with him A System of Universal Geography on the Principles of Comparison and Classification. Willard and Woodbridge created the first widely used historical atlas of the US. The maps, graphs, and pictures integrated details of the nation’s geography into the broad popular image of the country as a large, powerful complex nation.

Mapping Time

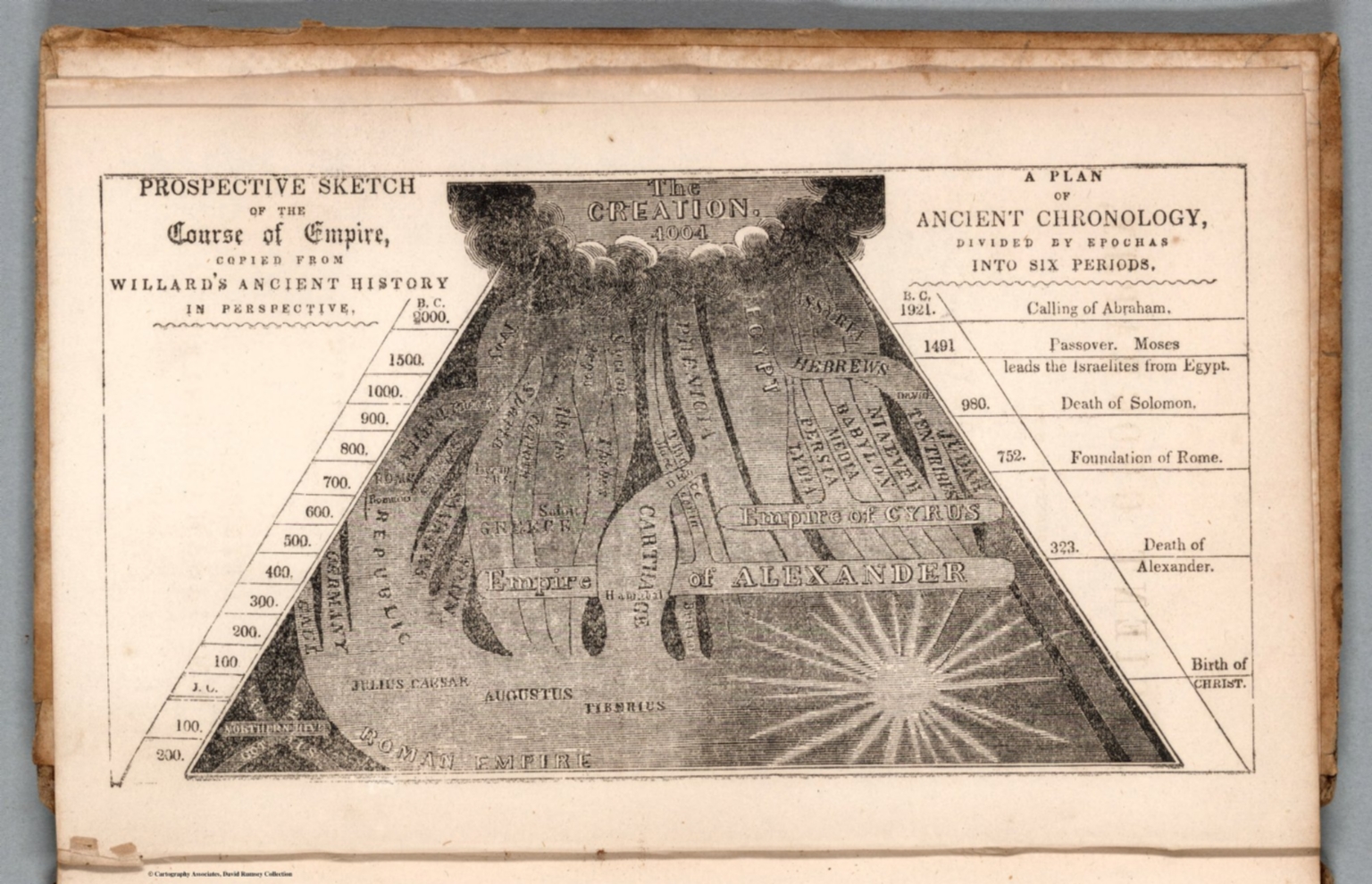

Prospective Sketch of the Course of Empire…A Plan of Ancient Chronology

Susan Schulten, Professor of History at the University of Denver, noted how Willard uses all aspects of visual design to convey meaning:

Emma Willard sought to invest chronology with a sense of perspective, presenting the biblical Creation as the apex of a triangle that then flowed forward in time and space toward the viewer. Commenting on her visual framework in 1835, Willard noted that individuals experience the past relative to their own lives, for “events apparently diminish when viewed through the vista of departed years.”

In “Perspective Sketch of the Course of Empire”, she found striking ways to represent this dimensionality of time. The birth of Christ, for example, is marked with a bright light, marking the end of the first third of human history. The discovery of America separated the second (middle) from the third (modern) stage. Each “civilization” is situated not according to its geography, as on a traditional map, but according to its connection and relation to other civilizations. Some of these societies are permeable, flowing into others, while others, such as China, are firmly demarcated to denote their isolation. By studying this map, students were encouraged to see human history as a rise and fall of civilizations — an “ancestry of nations”.

Moreover, as time flows forward the stream widens, demonstrating that history became more relevant as it unfolds and approaches the student’s own life. Historical time is not uniform but dimensional. On the one hand, this reflected her sense that time itself had accelerated through the advent of steam and rail. Traditional timelines, she found, were only partially capable of representing change in an era of rapid technological progress. Time was not absolute, but relative. On the other hand, Willard’s approach reflected her own deep nationalism, for it asked students to recognize the emergence of the United States as the culmination of human history and progress.

Willard aggressively marketed her “Perspective Sketch” to American educators, believing it to be a crucial break with other materials on the market. As she confidently expressed to a friend in 1844, “In history I have invented the map”.3 She also advocated for her “map of time” as a teaching device because she strongly believed the visual preceded the verbal — that information presented to students in graphic terms would facilitate memorization, attaching images to the mind through the eyes.

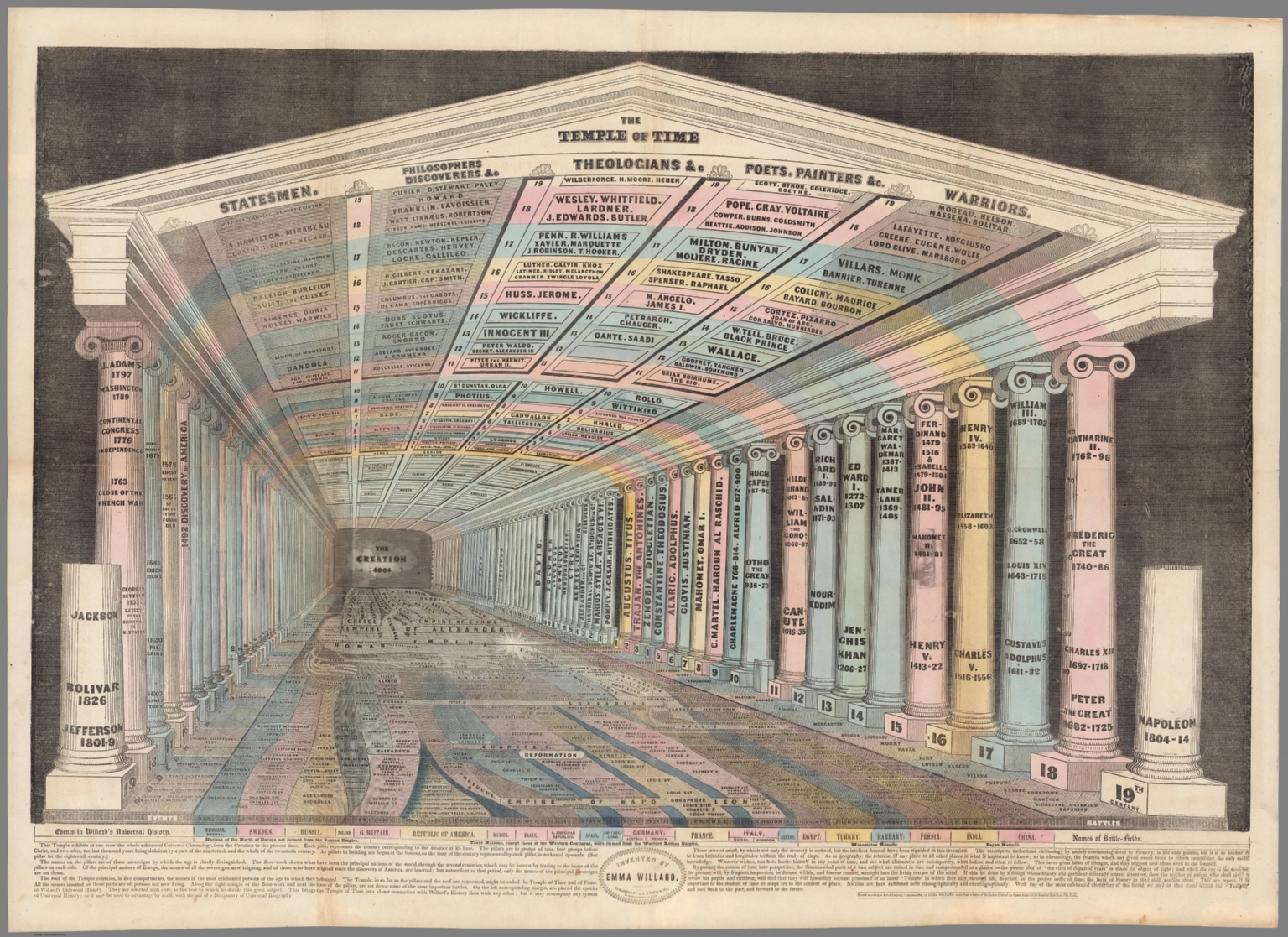

The Temple of Time

In the 1840s, Willard published arguably her best work, the Temple of Time, a chart that showed chronology as geography. This would serve as a memory place, to which all events could be added.

“…the stream of time she had charted in the previous decade now occupied the floor of the temple, whose architecture she used to magnify perspective through a visual convention. Centuries — represented by pillars printed with the names of the era’s most prominent statesmen, poets, and warriors —diminished in size as they receded in time, turning the viewer’s attention toward recent history, as in the “Course of Empire”. But in the Temple of Time, the one-point perspective also invited students in to inhabit the past, laying out information in a kind of memory palace that would help them form a larger, coherent picture of world history. Readers, in other words, were invited into the palace, so they too could stand at moments in world history.”

Willard said of her Temple of Time:

In a map, great countries made up of plains, mountains, seas, and rivers, are represented by what is altogether unlike them; viz., lines, shades, and letters, on a flat piece of paper; but the divisions of the map enable the mind to comprehend, by proportional space and distance, what is the comparative size of each, and how countries are situated with respect to each other. So this picture made on paper, called a Temple of Time, though unlike duration, represents it by proportional space. It is as scientific and intelligible, to represent time by space, as it is to represent space by space.

A map, in other words, is an arrangement of symbols into a system of meaning — and we use maps because we understand the language of signs that undergirds them. If the mapping of space was a human invention, she explained, one could also invent a means of mapping time.

Learning by rote was limiting and dull, he reasoned. Investigating the world through art and design was better. She continued

“The attempt to understand chronology by merely committing dates to memory, is not only painful, but it is as useless as to learn latitudes and longitudes, without the study of maps. As in geography, the relation of any place to all other places is what is important to know; so in chronology, the relation which any given event bears to others constitutes the only useful knowledge….

“By putting the course of time into perspective, the disconnected parts of a vast subject are united into one, and comprehended at a glance;–the poetic idea of “the vista of departed years” is made an object of sight; and when the eye is the medium, the picture will, by frequent inspection, be formed within, and forever remain, wrought into the living texture of the mind. If this be done by a design whose beauty and grandeur naturally attract attention, then the teacher or parent who shall place it before his pupils and children will find that they will insensibly become possesses of an inner “Temple” in which they may, through life, deposite[sic], in the proper order of time, the facts of history as they shall acquire them. This we repeat is as important to the student of time as maps are to the student of place.”

Willard’s 1846 chart Temple of Time won a medal at the 1851 World’s Fair in London and earned the praise of Prince Albert.

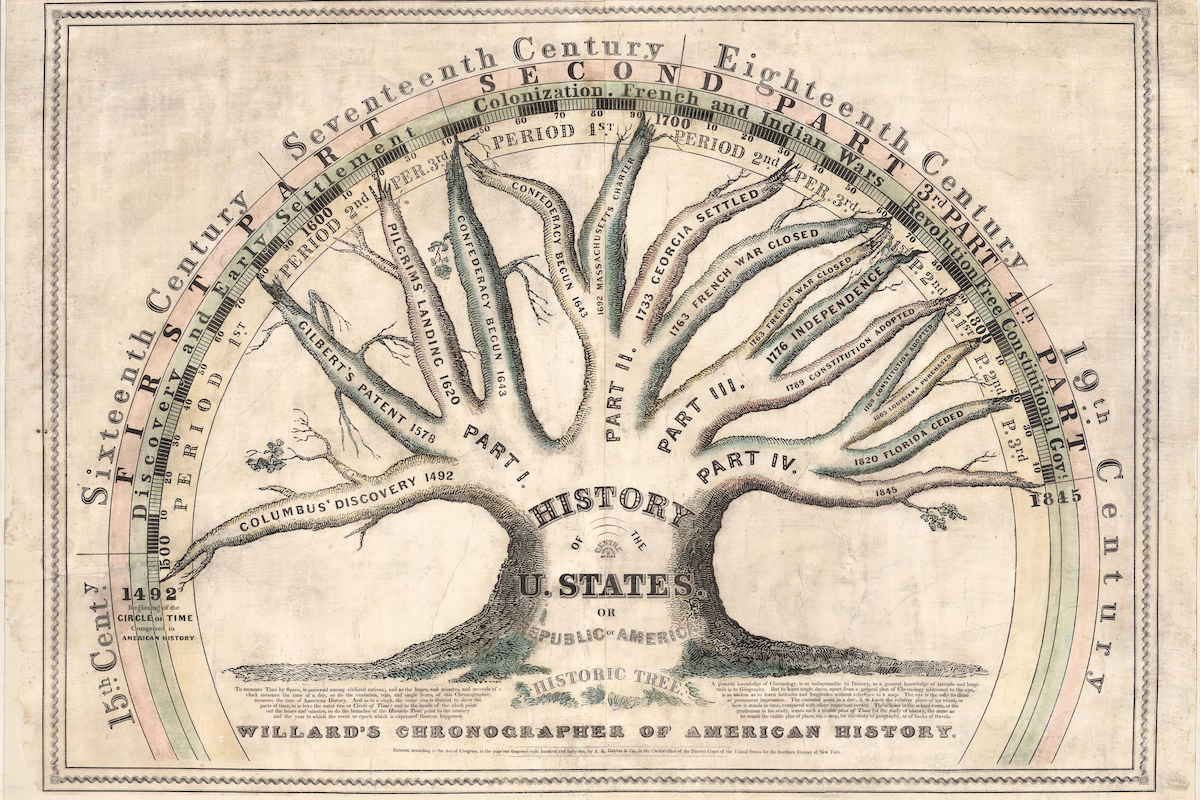

The Tree of Time (1845)

Willard’s Tree of Time presented American history in its entirety, extending to 1492 – all things linked and inter-reliant on their existence and growth. The Tree of Time is full of meaning, purpose and direction. She used it to introduce all subsequent editions of her popular textbook History of the United States and even issued it on a much larger scale to be hung in classrooms.

Ironically, it was the cataclysms of the Civil War that challenged Willard’s harmonious picture of history in the Tree of Time. In the 1844 edition of the Tree, President Harrison’s death marched the last branch of history. Twenty years later, Willard added a new branch marking the end of the US war against Mexico and the subsequent Compromise of 1850, seismic events which both raised and temporarily settled the sectional divisions over slavery. Even though the Civil War was well underway by the time she issued her last edition of tree, she marked the last branch as “1860”, with no mention of the bloody conflict that had engulfed the entire nation. Her accompanying narrative in Republic of America brought American history to the brink of war, but no further. Willard had come up against history itself.

Emma Willard

The sixteenth of seventeen children, Willard grew up in an era when girls were barred from formal education beyond primary school. In her long life, far exceeding her generation’s life expectancy, she went on to become a pioneering educator, founding the first women’s higher education institution in the United States when she was still in her thirties. Willard understood that improving the future requires a robust understanding of the past, so that one may become an informed, engaged, and effective agent of change in the present. In her early forties, she set about composing and publishing a series of history textbooks that raised the standards and sensibilities of scholarship. In 1828, having just turned forty, she authored what would become the country’s most widely read history textbook: History of the United States, or, Republic of America….

By the age of 13, she taught herself geometry and had enrolled in the Berlin Academy in Connecticut, where she attended for two years before becoming an instructor there. At the age of 19, she was offered a summer teaching job at a girls’ school in Middlebury, Vermont.

However, her experience at these “finishing schools” for young women—focused so intently on preparing them for the roles and responsibilities society imposed on them at the time—inspired her to chart a new course. In 1814, just 26 years old and bearing a financial burden from her father’s passing and outstanding debts, Emma Willard opened a new kind of boarding school for intellectually curious women out of her home in Middlebury. This “Middlebury Female Seminary” operated out of Madame Willard’s living room for five years, a fledgling foundation for what would become a transformational educational institution.

Writing 100 years before American women earned the right to vote and thus to steer the course of their country, she appealed to the patriotic spirit by framing the advancement and empowerment of women as a pathway to progress and a means to attaining “unparalleled glory” for the nation:

Ages have rolled away; — barbarians have trodden the weaker sex beneath their feet; — tyrants have robbed us of the present light of heaven, and fain would take its future. Nations, calling themselves polite, have made us the fancied idols of a ridiculous worship, and we have repaid them with ruin for their folly. But where is that wise and heroic country, which has considered, that our rights are sacred, though we cannot defend them? that… we are an essential part of the body politic, whose corruption or improvement must affect the whole?

See more stories about visualising data here.

Via: Public Domain Review, David Rumsey, Nightingale

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.