I must say that one single thing struck me, that a single thing sticks in my memory: I see myself, from the start of the Tour de France, like a bull pierced by banderillas, who pulls the banderillas with him, never able to rid himself of them.

— Maurice Garin, winner of the first Tour de France

The Tour de France has come and gone, delayed but not defeated by the coronavirus. In a joyous statement, 2020 winner Tadej Pogacar drives home how much cycling’s most high-profile professional event has changed since its rough-and-tumble origins in the early years of the 20th century. “It was not me racing today,” says Pogacar of his final stage to victory. “It’s the fruit of teamwork from the day we reckoned the course. I knew every corner. I knew where to accelerate. After the great job of my staff and teammates, I just had to push on the pedals.”

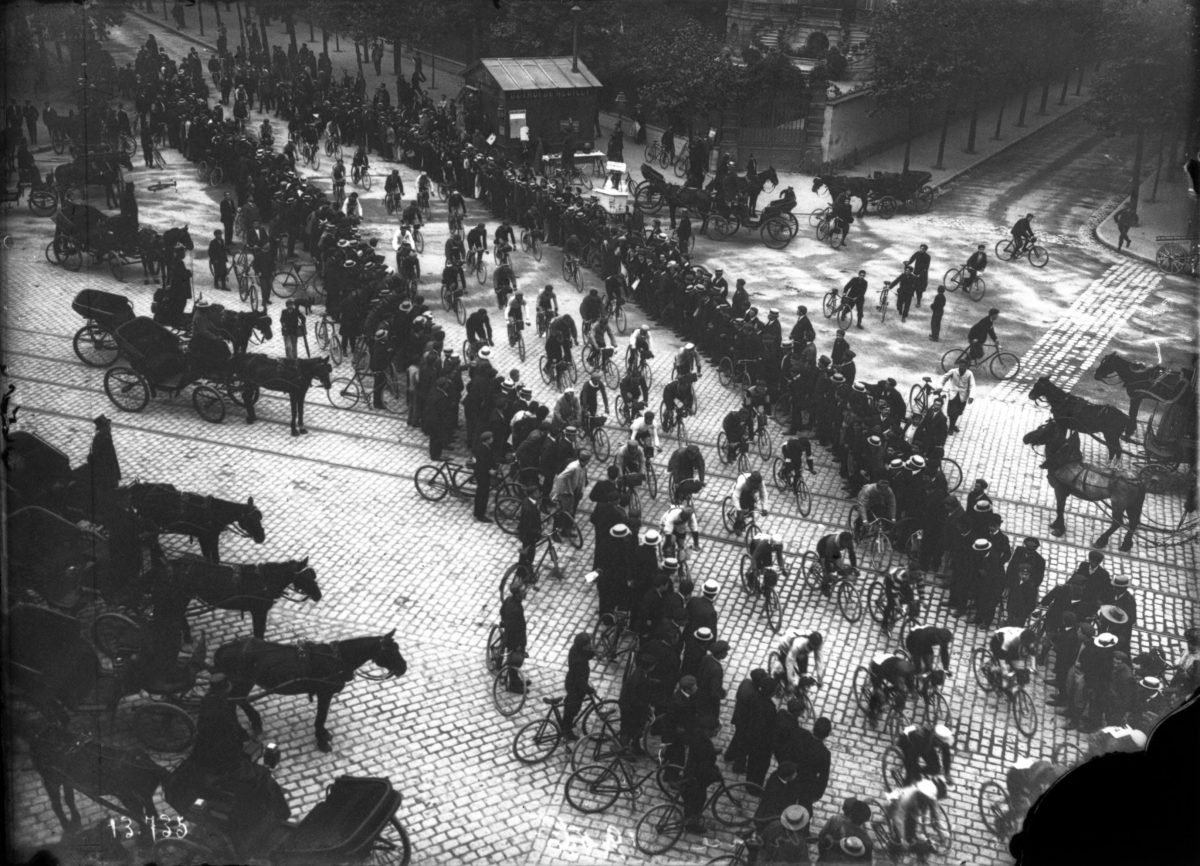

In the first Tour de France – the very first multi-stage cycling race of its kind – no teams were allowed. Moreover, the first tour’s competitors “rode into unexplored territory” in 1903, the year of the first race, EF Pro Cycling explains. Racers had no idea what to expect. “Most people in France never travelled very far from where they were born” since “one could only get from place to place by horse-drawn carriage or foot, or by bike, though bicycles were still a fairly recent and expensive invention.” They were not vehicles made for a 2,428 km race around the country.

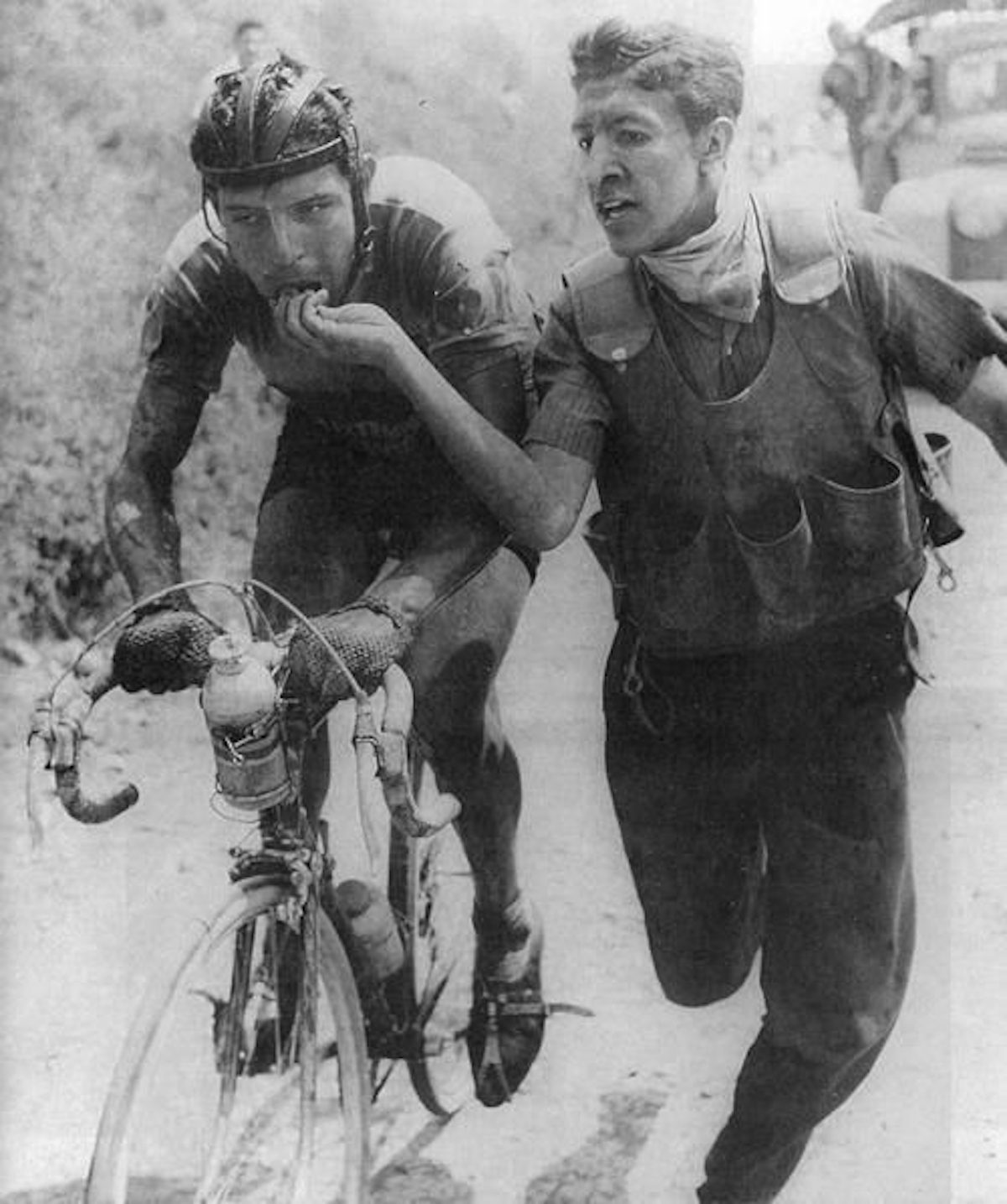

The first tours were more like what is now called adventure or endurance racing than the smooth, calculated road races we’re used to seeing on TV. They were undertaken on unpaved “gravel or cobbled roads with single-speed bikes in the summer heat” – heavy, cumbersome bikes with unreliable brakes and easily punctured tires – bikes designed for local deliveries and Sunday outings, that is. (Contrast the first winning bike with the last, just for fun).

But the race was no less competitive for its less-than-ideal equipment. Most of the 60 original competitors were amateurs, fighting for a grand prize worth six times the average yearly salary. The fledgling sport evolved slowly into a professional. It took quite some time for bike technology to improve as well. For several years, no gears were allowed, and riders were forced to use wooden rims rather than lighter, faster, and far more reliable aluminum.

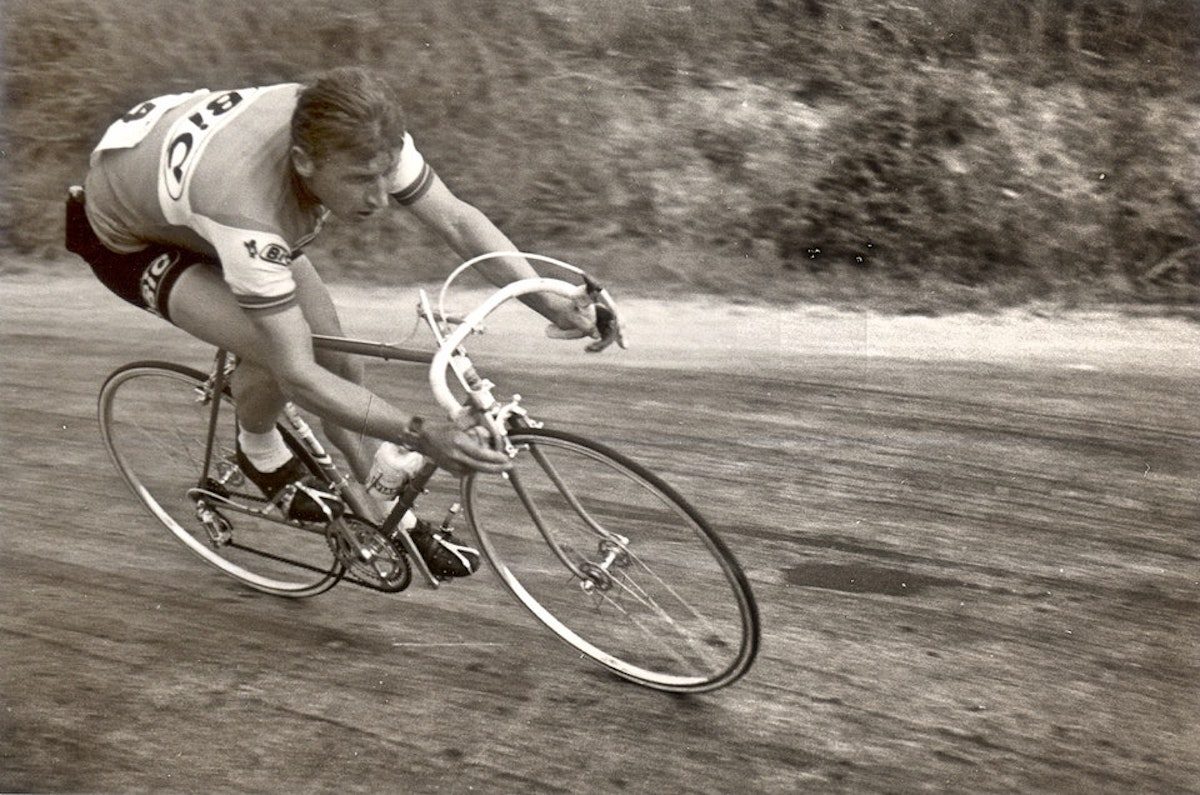

Jacques Anquetil, the last rider to win the Tour de France using the “clanger” derailleur, in 1957

Their heavy bikes were weighted down even further by tools. “It was not uncommon,” writes Road Cycling UK, “for riders to attach saddlebags and pumps to their bikes given at the time it was against Tour rules to receive external mechanical help – a far cry from today.” Over time, manual gear changes, then rod-actuated derailleurs, or “clangers,” became standard, as well as aluminum rims and other features of the racing bike that stuck around until strong, lightweight carbon, indexed cable-shifting, and huge, well-supplied support crews took over.

These days, international teams drawn from all over the cycling world compete for glory. In its early years, cycling was an extreme sport dominated by rugged individuals from all possible walks of life. Some things, however, haven’t changed much. From its beginnings, the world’s greatest cycling race was a promotional spectacle, first started by journalist and cyclist Henri Desgrange to increase sales of his newspaper L’Auto. By the time the final 21 racers to make it to the end crossed the finish line, “they were national heroes,” EF Pro Cycling writes. “The journalist’s publicity stunt had paid off. L’Auto’s readership had risen from 25,000 per day to over 130,000 during the Tour.”

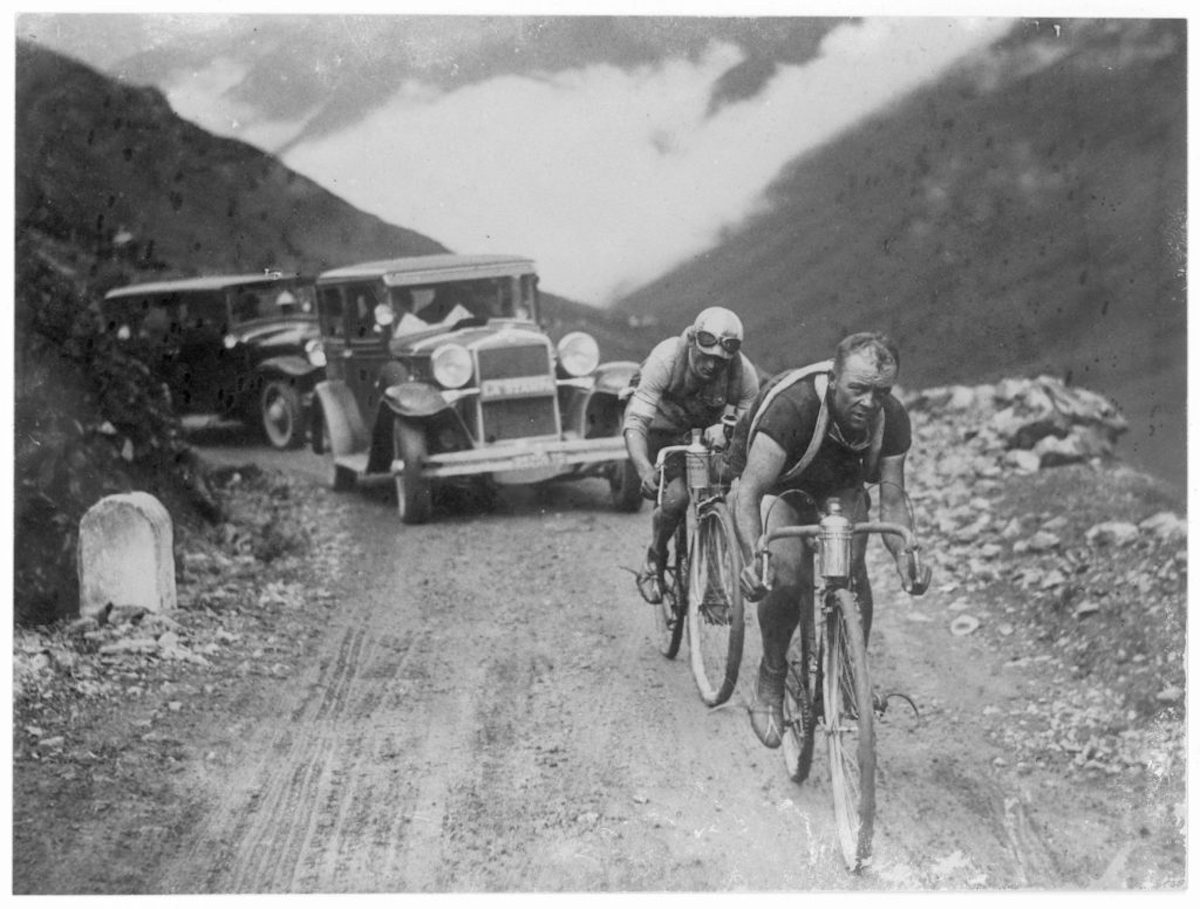

Roger Lapebie (pictured right) achieved the overall victory in the 1937 edition of Tour de France. Lapebie managed to pass a set of railroad tracks here while his pursuers did not.

And just as doping scandals have dogged the sport, bringing down heroic Lance Armstrong in the process, since at least the 1960s, various forms cheating were endemic to the Tour from the start, surrounded, as James Stout writes, by an “omerta.” Historian Peter Cossins describes in The First Tour de France how first winner Maurice Garin supposedly formed a team, against the rules, and turned them into his domestiques. After goading one of his “teammates” into pushing another rider to the ground, Garin then stomped the competitor’s bike to pieces. Officials overlooked the offense, though he was disqualified the following year for similarly aggressive antics.

So there you have it: placing asterisks next to certain winners’ names is as traditional as cycling’s racism and the combative tactics riders have always used to get ahead – all part and parcel of the longest, most grueling, and most renowned bicycle race in the world.

Léon Despontin, Stage 2 of the 1925 Tour de France

One of the competitors cycles in Romilly-sur-Seine (1936)

Raphael Geminiani descends the Col du Tourmalet in the French Pyrenees during the 18th stage of the Tour de France, 1952.

Eddy Mercx conquering the Mount Ventoux in 1969

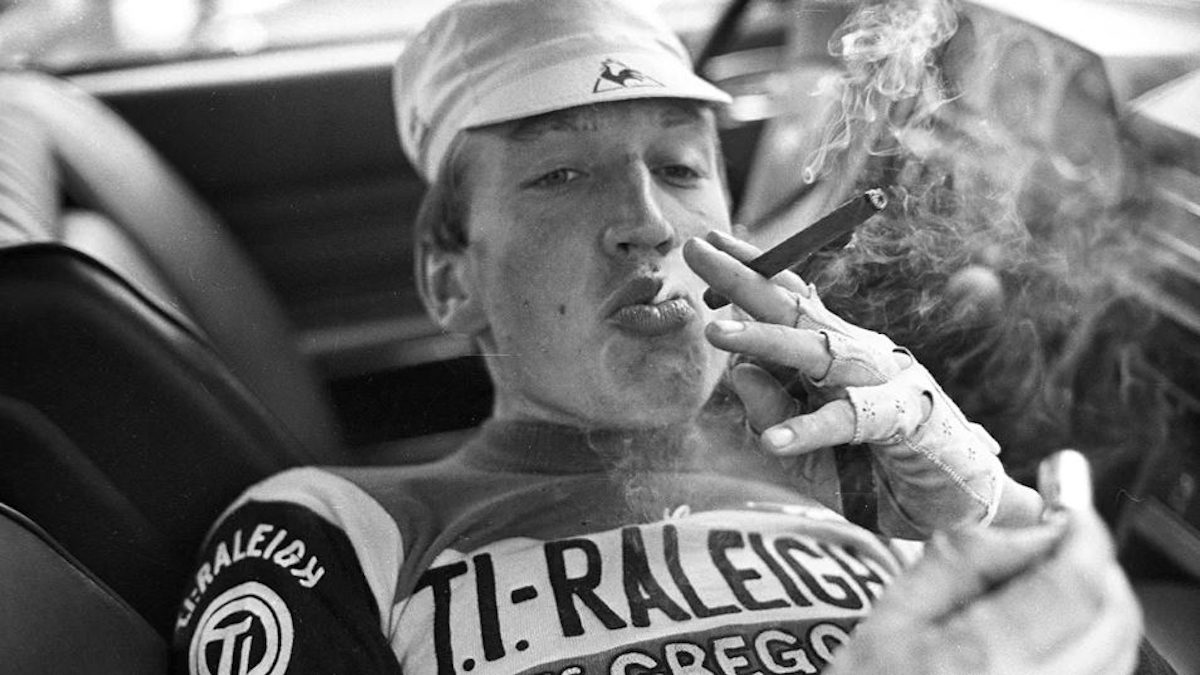

Aad Van den Hoek during a smoking break (1978)

Riders take a break in 1960

Cooling down in 1960

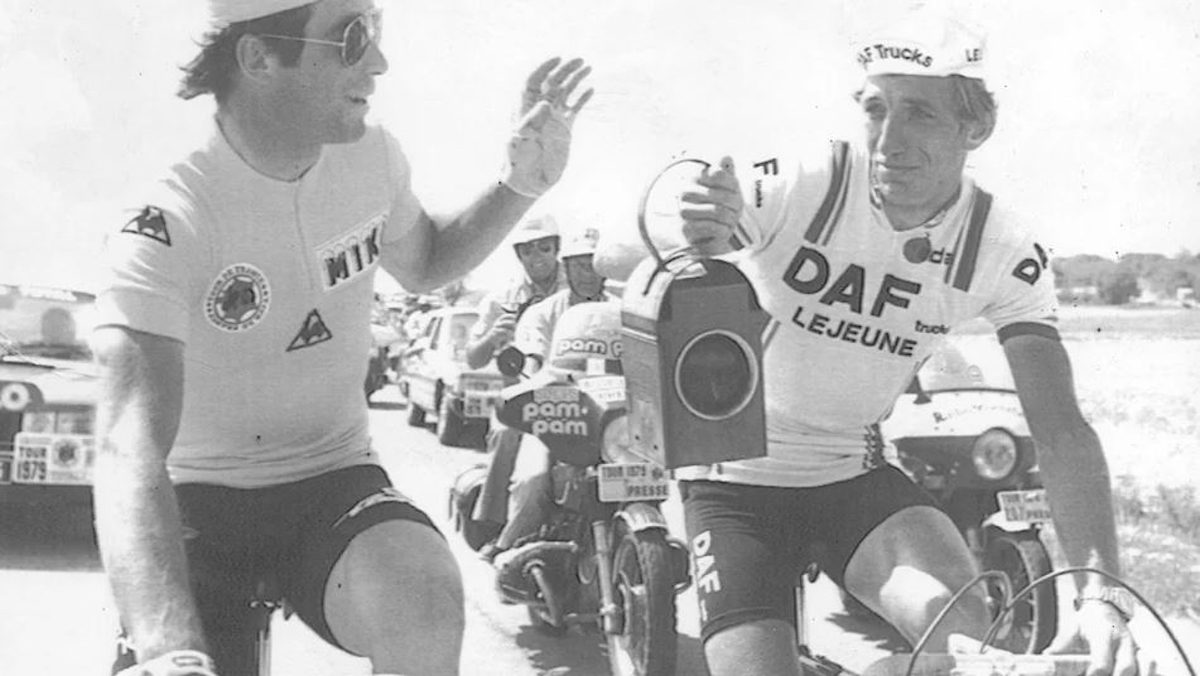

Bernard Hinault gives Gerhard Schönbacher a red lantern for taking last place (1979).

Fueling up in 1936

Refreshments (1964)

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.