“Man, I’ll play anywhere they’ll listen,” he said, “I’ll blow anywhere. The horn don’t dig those race troubles”

– Louis Armstrong

Let’s start this story, a story about resonant old songs and old prejudices, of dynamite and jazz, of segregation and schools, where so many of these kinds of stories start, so many stories of American racism, in a small town, with white men carrying guns.

Chilhowee, on a bend in the Little Tennessee River beneath Chilhowee Mountain, was a Cherokee town. Its people sang love songs and war songs, composed or improvised. They sang of violence and memory. In late 1781, as the newly United States were set to win the Revolutionary War, Thomas Jefferson, then governor of Virginia, sent men to the lands around Chilhowee. On Christmas Day, they burned the village to the ground. According to a letter that the commanding officer wrote to Jefferson, the soldiers destroyed eleven “principal towns,” “besides some small ones, and several scattered settlements… all of which were committed to the flames.” “The undertaking had something singular in it,” the commander wrote, “and may lead to important consequences.”

Seven years later, after Chilhowee had been rebuilt, white men came again. This time, the white men carried white flags as they entered the village, as if they came in peace. Chief Oskuah, known to the white men as Old Abraham, came out with his own white flag. The Maryland Gazette called it “a flag of truce, a protection inviolable even amongst the most barbarous people, in the character of ambassadors.”

The white men’s flag was a trick. They killed Old Abraham and eight others, scalped them with tomahawks, “brained.” The killings, the papers said, were carried out with “all the malice, horror and implacable hatred imaginable.”

The stories of the murders circulated for generations. The names passed into folklore.

For miles around, places were named for Old Abraham, and the once lost Chilhowee.

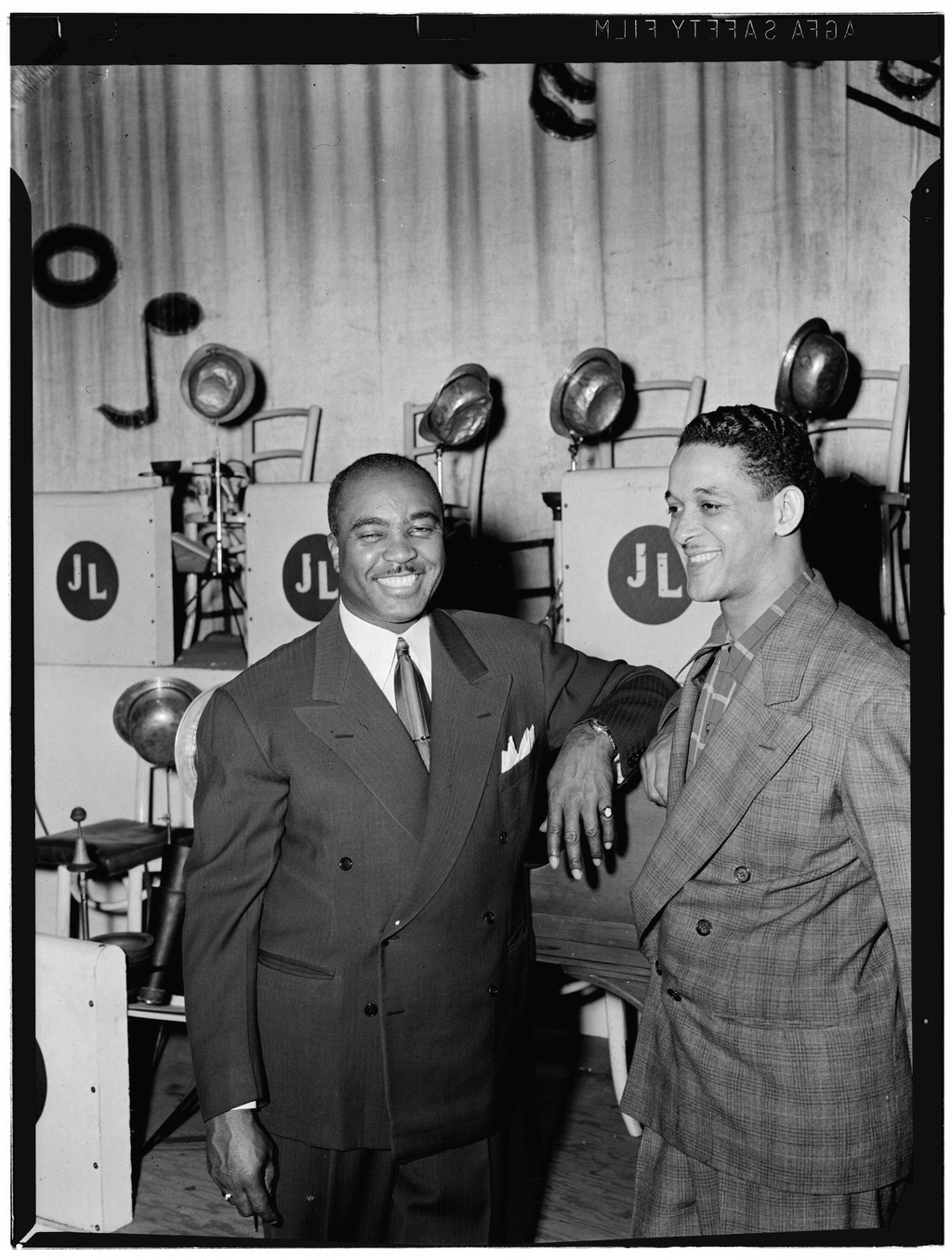

Louis Armstrong And His All-Stars at the Jacob Building, Knoxville, February 1957

When Louis Armstrong played at Chilhowee Park, in Knoxville, Tennessee, in February 1957, the stories of Old Abraham’s village were still being told, and were freshly relevant. South of the city, the Chilhowee Dam was nearing completion, damming the river and covering the site where the village had been, to generate electricity for the nearby aluminium plant, and for radios and record players across Tennessee. Archaeologists tried to save what remnants of Chilhowee they could find.

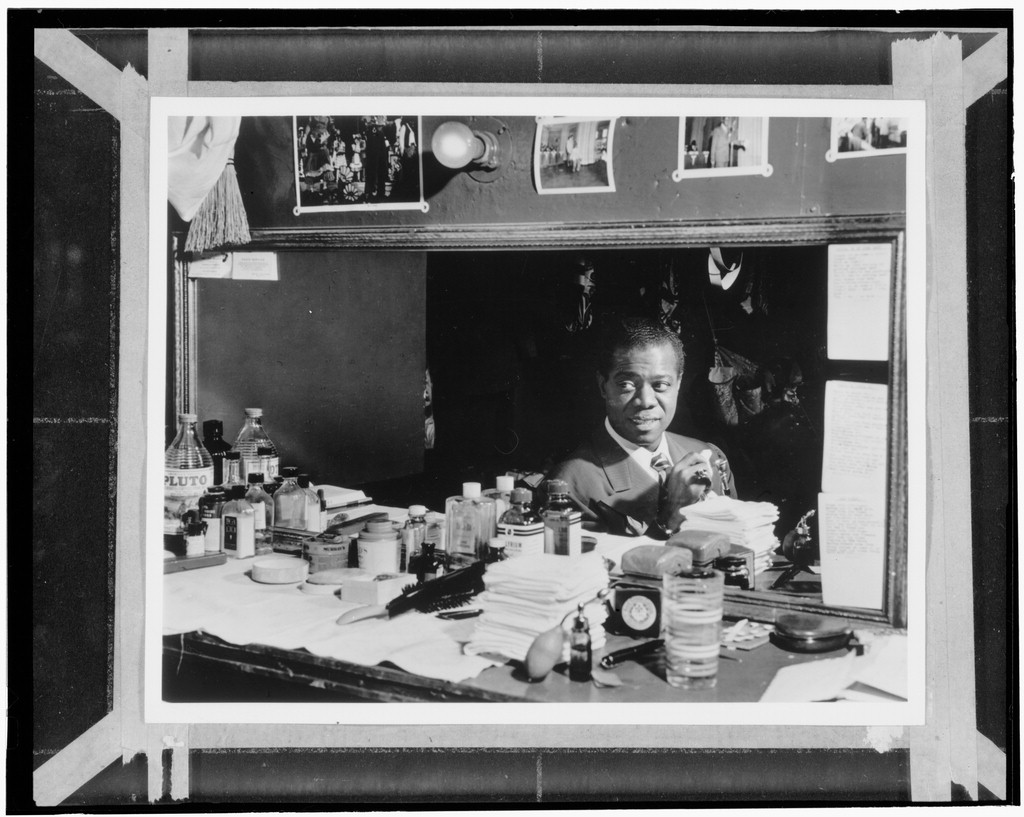

This was a long tour for Armstrong, with sixty-one dates across the South. The band played the first half of their set uneventfully, inside a grand building built on a hill over the lake in the park. There were a thousand black people in the audience, maybe a couple of thousand, on the floor beneath the stage. Looking down from the balconies, eight hundred, perhaps a thousand, white people hung above them. White women seemed to hover behind Armstrong, their coats draped on the rails, with the white men in ties. From time to time, at gigs here, a whisky bottle would smash around the black dancers, thrown from above.

Chilhowee Park had long brought prestige to Knoxville. Laid out in the nineteenth century on farmland owned by a Confederate general, its lawns and lakes, its places for theatre and dancing, drew visitors and their money. There were “National Conservation Exhibitions” commemorating the South’s industry and history. Presidents came to admire the displays, and the separate “exhibits of the handiwork of the colored race.”

When the original exhibition building burned down in the nineteen thirties, it was replaced by something with the same outline, with broad steps up to the square front, and long wings at either side, with impressive pillars and columns. They called it the Jacob Building, named for Dr Moses Jacob, then President of the Tennessee Valley Agricultural and Industrial Fair Association, who held fairs in the park, and still do.

Locals were proud of what the park had to offer. According to a 1954 advertisement in the Pittsburgh Courier, placed by Knoxville businessmen and union leaders targeting its northern black readership, “all the excitement of a fairyland lures old and young to Chilhowee Park, which is operated on a non-segregated basis. Children of all races, creeds and colors enjoy the amusement and recreational facilities of the park. Racial harmony is at its best here.”

In time, the park became well-known as a music venue. Louis Armstrong first played at the Jacob Building when it was still new, at Emancipation Day celebrations in 1937. By the nineteen fifties, gigs for white fans nestled next to gigs for black fans: one night the Cherokee Indian Square Dancers, the next Louis Price; sock hops arranged by a local r’n’b radio disc jockey, then the “Hillbilly Homecoming.” Gigs intended to appeal to both black and white audiences, like Armstrong’s return in 1957, were strictly segregated.

This then forms the setting for this story, a very American setting for a very American story: a park named to evoke a massacre, built on Confederate land, a site commemorating white history and black music, a place riddled with old ghosts, place of racial harmony and of segregation.

After a short intermission, at about twenty to eleven, Armstrong’s band began playing ‘Back O’ Town Blues’. The song was a crowd favourite, full of well-honed asides where the band would call out to Armstrong, commenting on the lyrics – “that’s just like you, Pops” – and he would respond, laughing. Some nights he would introduce it as “a good ol’ good one I wrote,” or say that the song would “take you down to New Orleans, folks.”

Armstrong wrote the song back in 1923, shortly after he made his first recordings with King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. At first, he didn’t intend to perform it himself. Published under the pseudonym “Herbie Herbedeaux,” he wrote it to sell to white performers during the blues boom of the early twenties. The French-sounding pseudonym, with its playful drug references, was designed to appeal to white fans who wanted apparently authentic “Creole” jazz.

Like ‘Canal Street Blues’, which Armstrong had just recorded with King Oliver, and ‘Rampart Street Blues’, which was also written in 1923 and credited to “Herbie Herbedeaux,” Armstrong based the song on an area of New Orleans: the Back O’ Town neighbourhood where he spent his earliest years. He gave the song a subtitle for the sheet music, which seems never to have been taken up: ‘A New Orleans Blues’. Despite hiding behind a pseudonym, and aiming for a generic blues market, he pinned the song to the specifics of his hometown memories.

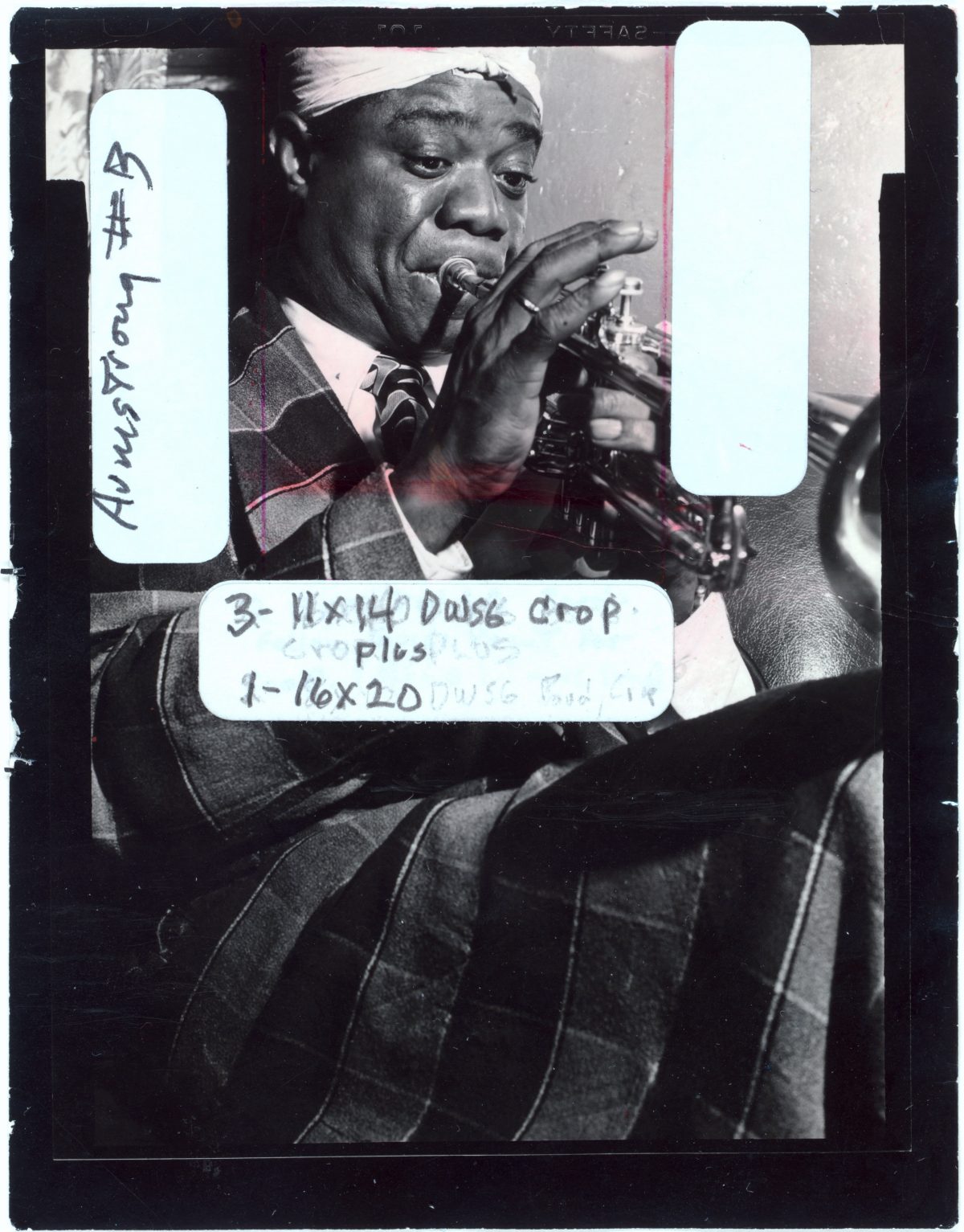

Portrait of Louis Armstrong, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., ca. July 1946

Despite its specificity, the white bands who first recorded ‘Back O’ Town Blues’ traded under names that conjured an imagined, appropriated black South: The Memphis Five; The Original Indiana Five; The Black Dominoes; The Cotton Pickers, who issued ‘Back O’ Town Blues’ backing ‘Rampart Street Blues’. One widely-circulated review of The Cotton Pickers’ version suggested it took the listener “straight back to New Orleans, to the land where the sweet, sweet mammas grow.” Some heard the song as a novelty. One advertisement commented on its “weird and amusing sounds” and “rollicking peppy syncopated tempo, which keeps the feet a-going.” This was, the advertisement suggested approvingly, “not jazz music.” Even this early in his career, Armstrong’s real life became the stuff of pastiche.

Armstrong didn’t record the song himself until the mid-forties. By then, it was a revivalist tune, marking his shift away from big bands back to small groups. Reviewers noted its nostalgia: “Armstrong, on this disc, is again the Armstrong who made ‘West End Blues’ and ‘Mahogany Hall Stomp’; “his trumpet shows up in something of the old manner, and his vocalizing is humorous and not over-powering”; “the master’s voice and trumpet are heard.”

Barrett Deems performs with Louis Armstrong band and Velma Middleton in Oslo, Norway in 1955.

In 1955, Armstrong released a new recording of the song, as the b-side to his hit version of ‘Mack The Knife’. It was a live regular by then, what the press called “his old standby.” The surviving live versions from this era show the song changing over time. Sometimes, it would be played slow and proud, parade style, or like the blues that Armstrong dreamed of playing as a boy, sat on the laps of the prostitutes and dancers who lived in Back O’ Town. Sometimes it would swing more, harking back to the big band arrangements he recorded in the forties. Sometimes, for a few bars, the song would lift, and leap to a newer style, drums and bass to the fore, a nineteen fifties style, more rhythm and blues than rhythmic blues. Sometimes there were shifts of rhythm, with drums hit hard by Barrett Deems, Armstrong’s white drummer, and percussive trombone played by Trummy Young. As first, the wandering bass was played by Arvell Shaw but, by the time of the Knoxville show, Armstrong had recruited a white bassist, Squire Gersh. The band would play loud and heavy. Armstrong would smile and laugh, and he’d mutter at the end, as if to himself, “that ain’t no stage joke either, daddy.”

What did Armstrong think as he played it in Knoxville? Although some in the audience undoubtedly thought the song was about a generic downtown, it’s hard not to imagine Armstrong thinking of the real Back O’ Town as he played it. What about the woman that he sang about, night after night? Was she someone specific too, this woman who “treated me right, never let me down”? Was this a real memory that Armstrong recalled, just as Back O’ Town was a real place?

Even if she was merely a generic woman of the blues, there was certainly a real woman who lived in Back O’ Town that “treated me right.” It’s hard not to imagine Armstrong thinking of her as he sang before the segregated audience in Knoxville. Unlike other possible candidates, his first wife Lucy, say, or his mother Mary, this woman actually lived in the neighbourhood, with Armstrong himself.

Josephine, Armstrong’s grandmother, loomed large for Armstrong. She raised him in his earliest years, and her stories helped form him.He wrote in his autobiography, of her stories about her days as a slave, “sold on the hoof like cattle,” of dancing the bamboula or conjaie in Congo Square. Perhaps ‘Back O’ Town Blues’, a crowd favourite for decades, easy to laugh along to, a fun song, slow and then forceful, played at a venue where he had celebrated Emancipation Day long ago, was a song for a former slave with a long memory.

Whatever the song meant to Armstrong or the audience in Chilhowee Park, it became this story’s soundtrack. It was the music playing when the explosion happened.

The noise from the dynamite reverberated around the Jacob Building, echoing under the balconies and the barrelled ceiling. A woman half a mile away heard it. A police sergeant in his car heard it, two miles away. Some said they heard it further away, five miles or so. As it resonated, Armstrong’s band continued playing that viscous, old, nostalgic blues.

Some of the audience below the band turned in the direction of the explosion. So did some of the those up in the balcony. A few left the building — half a dozen or so, Armstrong saw — but most stayed.

Someone ran onstage. A bomb had gone off, they said. Armstrong asked where. “Next door,” they said, as Barrett Deems remembered in the documentary Satchmo. “You can put your bus in the hole.”

“That’s all right, folks,” Armstrong told the crowd. “That sounded like a drunk falling out of the balcony,” he said, jokingly, and blew his trumpet like he blew his trumpet every night.

When the show finished, twenty minutes later, the remaining fans left the Jacob Building. They saw a hole outside, not big enough to consume Armstrong’s tour bus as Armstrong had heard, but four or five feet across, a foot and a half deep. Police officers peered in with torches. Mud covered the cars parked around the crater. Someone had seen a Chevrolet drive past with its lights out, and a stick of dynamite lobbed from the window.

Reporters asked Armstrong his views. He tried to play things down. “I feel like I could go right to Birmingham and play,” he said, thinking of the city where Nat King Cole had been assaulted onstage by a white supremacist the year before, “I don’t believe we’d have any trouble.”

“Man, I’ll play anywhere they’ll listen,” he said, “I’ll blow anywhere.”

“The horn don’t dig those race troubles.”

The next day, the newspapers focused more on Armstrong’s remarks than the bombing itself. He had carried on playing, they emphasised, ignoring the explosion, dismissing it. His comments were reprinted in newspapers in towns and cities across the country, across the world. Sometimes, they were printed with no further story, highlighting the quote, his humour and savoir faire presented as the most notable part of a terrorist attack.

Armstrong continued his tour, heading to Columbia, South Carolina. He was asked more questions.

He was “tuckered out,” he said, after the bus ride. “Man, I had no idea that thing caused so much static.”

“All I want to do is blow the horn. I’m from New Orleans, a Southern boy, I shouldn’t be afraid of anything, or excited. I mean the people all seemed to enjoy our music from the first note on.”

Armstrong knew this old racist mentality well, of course. In his autobiography, he remembered white men in his youth going “Nigger Hunting,” spurred on by “that bad whiskey the poor white trash were guzzling down like water.” He knew the racism of Tennessee, too: in 1931, he was arrested in Memphis, for sitting next to his manager’s wife, a white woman, on his tour bus.

Despite his experiences, and frequent criticism from fellow jazz musicians, he spoke about racism only rarely, and was often elusive when he did. “Somehow I have always been a greater attraction among whites than my own people, a thing which has always disturbed me,” he told the press, the summer before the show in Knoxville. “I have to love them and what they stand for to love myself. After all, it’s no secret what I am. I have my own ideas about racial segregation and have spent half my life breaking down barriers through positive action and not a lot of words… Certainly, I am concerned about what happens to my people, but I am trying to do something about it and not talk for headlines.”

Nevertheless, the increasing coverage of this kind of violence and discrimination made it harder for Armstrong to avoid comment. In his semi-official role as an “ambassador” for the State Department, Armstrong was frequently asked for his views. In London, in 1956, he told a BBC interviewer that “bad whisky” explained the “race violence” in the United States. The press called him a “happy ambassador of the United States,” a “very rare thing among musicians — a conservative who’s also fashionable,” though he was still a “back alley boy from New Orleans.”

When New Orleans passed a law in summer 1956, banning integrated bands in the city, Armstrong was again asked to comment. This was something he couldn’t play down. As J. Mark Souther details in New Orleans on Parade, trumpeter Ernest “Punch” Miller and five others were arrested in January 1957, weeks before Armstrong’s Knoxville show, for apparently “disturbing the peace” by playing in an integrated band. Armstrong’s response was firm. He refused to play the city of his birth without his white musicians.

“They treat me better all over the world than they do in my own hometown,” he said.

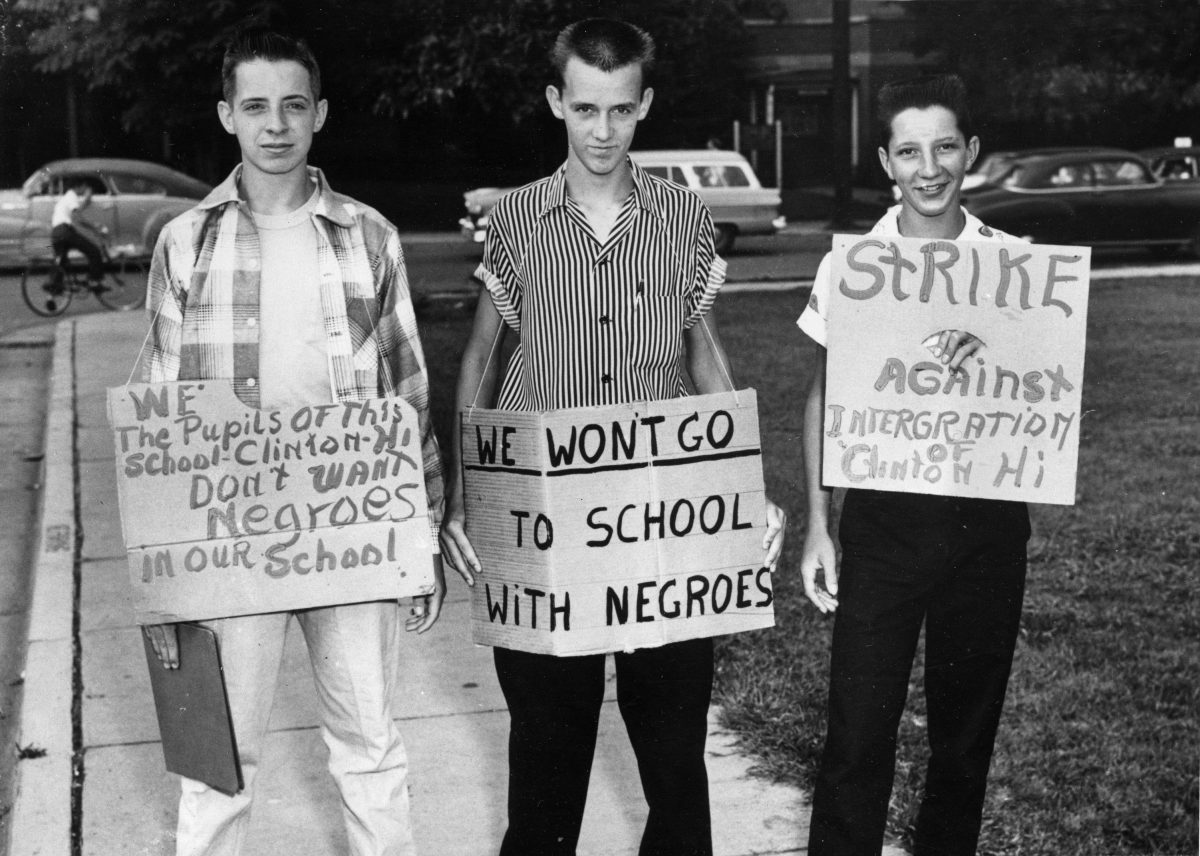

Three students at Clinton High School picket their school as it became the first state-supported school in Tennessee to integrate. The boys are, from left, Buddy Trammell, Max Stiles and Tommy Sanders. Trammell and Sanders later discarded the pro-segregation signs and reported to classes. Date: 27/08/1956

Segregationist protestors surround Elizabeth Eckford, one of nine black students to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1957. Reflecting on the experience decades later, Ms. Eckford observed, “True reconciliation can occur only when we honestly acknowledge our painful, but shared, past.” (Will Counts Collection: Indiana University Archives)

Students at the University of Alabama burn desegregation literature in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, on February 6, 1956, in response to the enrollment of Autherine Lucy. (Library of Congress/AP)

In late January 1957, mimeographed bulletins were attached to parked cars in Knoxville, decrying the “vulgar animalism that is displayed by the native performers at the Chilhowee Park ‘rock n roll’ sessions for the benefit of our youth.” “These jungle dances,” the bulletin said, were “the road to race suicide.” The note was signed by the “Tennessee White Citizens Council.”

The Tennesee White Citizens Council was led by John Kasper. He had come to the area in 1956, to protest the integration of Clinton High School, north of Knoxville, bringing with him the idea of White Citizens Councils, a national network of racist organisations, sometimes affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan.

In the early fifties, Kasper was part of the Greenwich Village bohemian set and ran a bookshop in the city. After starting regular correspondence with Ezra Pound, who was then detained in a hospital, unfit to stand trial for treason, Kasper moved to Washington D.C., where he formed his first White Citizens Council. He had long combined his protests against integration and popular music. Just as black people could not understand white history, he wrote, and so should be educated separately, white people could not understand “the joy a Nigra experiences in jumping around a campfire all night making weird sounds he calls music.” “We believe it’s Negro music and we don’t want our young White people to look up to Negro entertainers,” he told reporters. “We think Rock and Roll is an instrument of the NAACP to destroy racial identity.”

This was more than just rhetoric. Kasper, and others in the White Citizens Councils, both proclaimed and practised violence. It was Asa Carter, an associate of Kasper’s and fellow White Citizens Council leader, who had assaulted Nat King Cole onstage in Birmingham. Since Kasper arrived in Tennessee, there had been at least seven previous dynamite explosions connected to the high school protests, including an apparently accidental explosion outside offices rented by him for the White Citizens Council.

Just days before the explosion at Chilhowee Park, more dynamite exploded in Clinton. This time, the dynamite was hidden in a suitcase, outside a fast food restaurant in a black area of the town, close to the house where a black Clinton High School student lived. Thirty homes were damaged by the blast. A woman and an eleven month old baby were injured. “It has got to be a pressure down here which is more or less like a stick of dynamite,” Kasper said shortly beforehand, “and you throw it in their laps and let them catch it.”

Around the same time, Kasper began publishing a newspaper in Knoxville to spread his ideas, the Clinton-Knox County Stars and Bars. On the front page, Kasper identified fifteen Knoxville residents who he called “race mongrelizers.” He called for the city’s mayor, Jack Dance, to resign for what other newspapers called “his policy of permitting whites and Negroes to perform together before segregated audiences.”

There was a picture of a black saxophone player, surrounded by white teenagers, cheering. It was captioned “Chilhowee Park: 1957.”

After the explosion at the park, the story the press told wasn’t one of bombs and terrorism, or of centuries of violence. Their version of the story was of a good-humoured musician, where racial harmony was the norm, where explosions were an aberration.

Beneath a masthead proclaiming it “for 89 Years The South’s Standard Newspaper,” The Atlanta Constitution argued that “the tosser of dynamite was not upholding tradition.” The segregated audience at Knoxville, they said, was something that had been normal across the South, for decades. The Indianapolis Star, describing Armstrong as “black as the ace of spades,” praised him for not calling “the folks who threw the dynamite stinkers, which they deserved to be called. He didn’t rant and rave against prejudice and bigotry.” “Ol’ Satch’s trumpet has done more to bring down those bitter walls of Jericho that represent racial discrimination than two dozen sober-sided national conferences would have done,” the paper suggested. “With a couple of wisecracks the old Prophet of the Blues has shown up violence and discrimination for what they are, the work of the ignorant, the dull and cowardly.” The Statesman Journal suggested that “his brand of dynamite — popular music — has done much to bring status to Negro musicians.”

Like many papers, the Tennessean drew links with the earlier “dynamitings” in Clinton, “brought on by unrest over the integrated school there.” They reported on a Bill introduced in the State House of Representatives “aimed at curbing trafficking in dynamite by persons unauthorized to use it” to stop “the increasing use of dynamite as a weapon of destruction, intimidation and reprisal in this state.” The headline suggested it was “Time To Curb This Dynamiting Terror.”

Not all of the coverage was sympathetic. George E. Pitts, writing in the Pittsburgh Courier, found Armstrong’s joking dismissals of the incident “sickening. They make me think some Negro stars are so ‘hungry’ for the dollar that segregation is made a secondary issue. It makes me think that people like these have lost their self-respect and pride. When a Negro loses these he has nothing.” “It’s about time high-salaried Negro entertainers started doing something about being forced to play before segregated audiences in the South,” he wrote. “The Negro performers who carry through these un-American practices are responsible, too.”

Other papers hedged their bets. The Indianapolis Recorder, an historically black newspaper, carried a headline suggesting both that “Satch Outblasts Hate Blast,” and that “Satchmo ‘Fiddles While Dixie Rome Burns’.”

Inevitably, segregationists attempted to capitalise on the publicity. A few days after the explosion, the Knox County White Citizens Council tried to hire the Jacob Building for a rally. According to its “director of public information,” they were told it “is not available to use at any price.” “We have also been denied the use of any of the city school auditoriums,” he told the press. He complained, in that familiar way of racists, that freedom of speech was being “suppressed,” that “it seems we have no civil rights at all in Knoxville.”

Still on tour, Armstrong was asked about the bombings in Clinton.

“What’s Clinton?” he said.

The bombings continued.

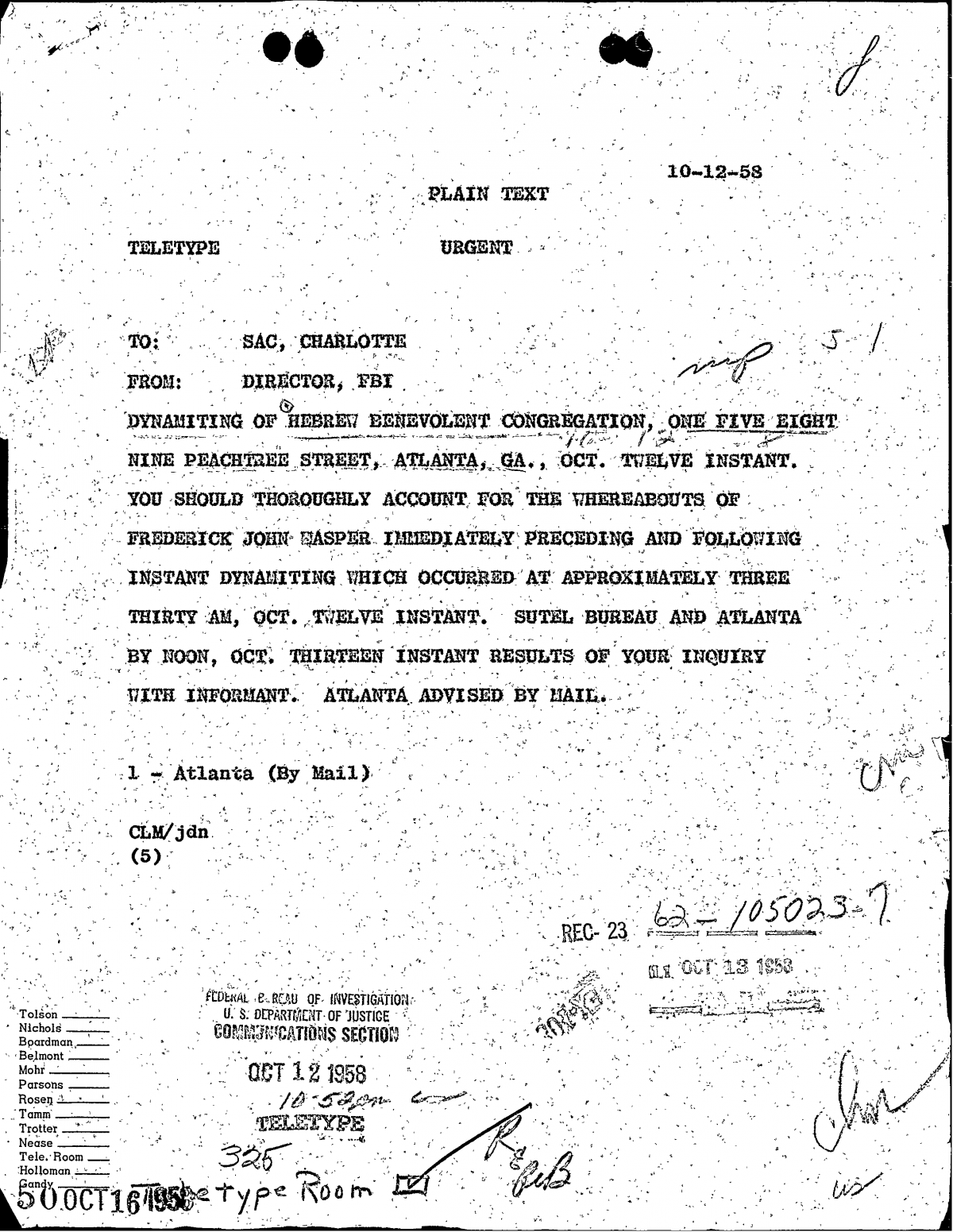

FBI teletype sent immediately after the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation Temple bombing, instructing agents to “thoroughly account for the whereabouts of Frederick John Kasper” before and after the time of the explosion

John Kasper speaking to a crowd, Nashville, TN, September 1957 – Nashville Public Library.

According to a report compiled by the FBI at the time, between January 1957 and October 1958 there were “93 known bombings and attempted bombings” across the country, a national wave of terrorism rarely seen before or since. The bombing at Chilhowee Park became just one of a long list: Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s house in Montgomery, Alabama; a juke joint in Jacksonville, Florida; synagogues and Baptist churches, in Georgia and Texas; a dance hall in Illinois; the home of children attending an integrated school in Maryland; houses bought by black families in white neighbourhoods in Michigan and Missouri and Oklahoma; a drive-in theatre in Charlotte, North Carolina; the home of a black farmer in Gaffney, South Carolina, who had employed a white woman to pick cotton.

In Tennessee alone, there were twenty incidents noted in the report: fifteen pounds of loose dynamite in front of the home of a Clinton High School student a few weeks after the explosion at Knoxville, and schools bombed in Chattanooga and Nashville, and a Jewish Community Centre, a church in Memphis, homes across the state. In October 1958, Clinton High School itself was destroyed by three dynamite explosions.

John Kasper featured prominently in the FBI report, and was a suspect in a number of the bombings. The FBI monitored his movements and his speeches, just as they did with Armstrong. Despite widespread speculation, no arrests were made after the Knoxville explosion. “Police said they had no idea where to begin looking for the person who planted the explosive,” the newspapers said. Shortly afterwards, Kasper was convicted of contempt of court, for his refusal to follow a court order to stop protesting at Clinton.

The press coverage seemed to have an effect on Armstrong. Despite initially playing it down, by September 1957, when the violence and protests against integration had spread to the high school in Little Rock, Arkansas, he told a reporter that “the way they are treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell.”

This was even worse than before, he thought. “My parents and family suffered through all of that old South and things are new now,” he said. “It’s getting so bad a colored man hasn’t got any country.”

![Louis Armstrong drawing a trumpet and autographing the side of a young man's head in Nice, France]](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Louis-Armstrong-drawing-a-trumpet-and-autographing-the-side-of-a-young-mans-head-in-Nice-France.png)

Louis Armstrong drawing a trumpet and autographing the side of a young man’s head in Nice, France – 1961

That, of course, is not the end of the story, the long story that went back to Old Abraham and beyond. The story of Chilhowee Park is barely old enough to be history. The teenagers in the segregated audience that night in Knoxville, or those at Clinton High School or those who protested with John Kasper, are now in their seventies. They now vote, and still listen to the radio.

They hear of Donald Trump, and the far right rising again, of the attack on the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, and the Route 91 Harvest festival in Las Vegas, of violence in Charlottesville and Ferguson and Standing Rock, of “very fine people on both sides.”

They listen to old songs, and some new songs. Music still brings us together and still separates us out. They choose their stations carefully.

Armstrong plays.

The story goes on.

– By JP Robinson, read him on Medium

Lead image: Portrait of Louis Armstrong, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., ca. July 1946 by William P. Gottlieb.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.