Dondi, Children of the Grave Again, by Martha Cooper

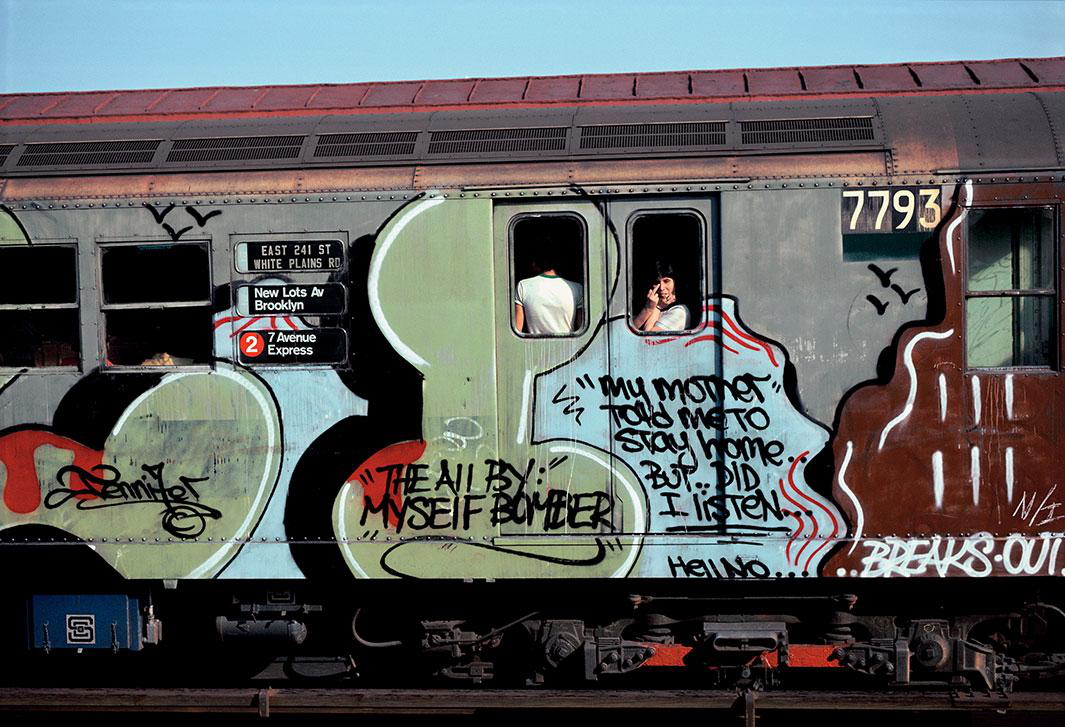

The origins of hip hop’s graffiti scene in the crumbling, decaying boroughs of NYC in the 1970s have by now become the stuff of legend, subject of countless documentaries, fictionalized series, academic studies, and popular books. But when photographers Henry Chalfant and Martha Cooper first published Subway Art, their seminal photo-journalistic document of the emerging art form, in 1984, the book attracted little notice. “After many rejections, and later poor sales when it finally did get published,” writes Christopher Lee Inoa at Curbed, “Cooper then thought that part of her life was over.” Little did the two photographers realize how influential their work would become, reprinted and exhibited all over the world.

Cooper – who was a member of the Peace Corps, had traversed Southeast Asia by motorcycle, and become the first female staff photographer for the New York Post before entering the train tunnels—focused her lens on other subjects until the publication of 2004’s Hip Hop Files brought her “back on the scene.” Chalfant continued to document graffiti scenes worldwide, publishing Spraycan Art in 1987 and, later, Training Days in 2015. Both photographers’ work now regularly appears in retrospectives around the globe, such as the Bridges of Graffiti exhibit at the 2015 Venice Biennale. They’ve gained respect not only for realizing the creative potential of an art form thought of as a criminal public nuisance, but also for the methods they developed especially for this work.

Freshly Painted Wild Style Wall in Riverside Park, by Martha Cooper

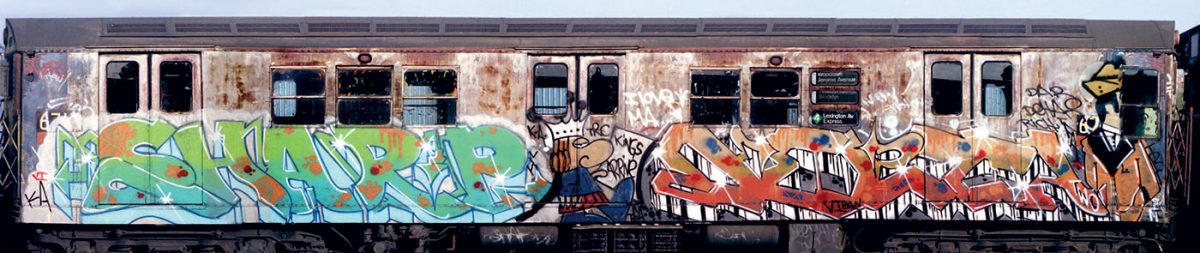

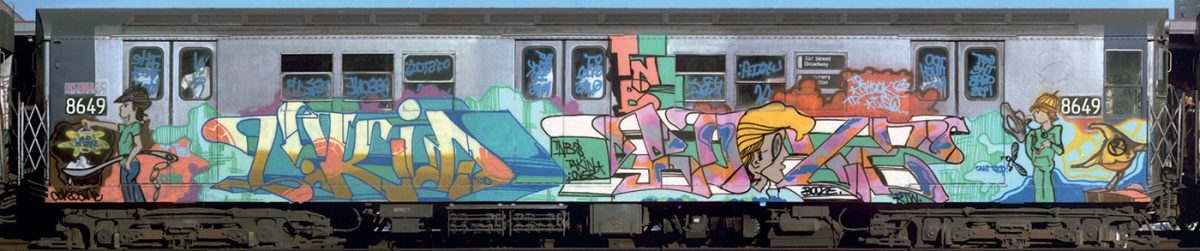

Decades before camera phones put panoramic photography in everyone’s hands, Chalfant “created a technique of shooting exposures in continuous, rapid succession on a 35mm camera,” notes Untapped New York, “so that he could document the entire train by stitching the overlapping images together. His body of work helps retain artwork that, by its nature, has disappeared, and a form that is rarely see, following the efforts of NYC Transit to clean trains shortly after they are tagged.” What Chalfant and Cooper captured went far beyond “tagging,” though that term accurately describes the early genesis of graffiti culture in the late 1960s.

Sharp, Delta, by Henry Chalfant

What began as a way for young people in neglected urban areas to achieve some measure of fame and recognition became “a democratic art form that revels in the American Dream,” says sociologist Gregory Snyder, author of Graffiti Lives: Beyond the Tag in New York’s Urban Underground. John Matos, a graffiti artist known as Crash, puts it a little differently:

What we were doing was using a language among ourselves and talking to each other. Henry brought an intellectual eye to it, and I guess that was needed. He was able to manifest our language to the public so they could see it differently. He brought a clandestine thing out into the open.

Graffiti art’s explosion into the mainstream brought new levels of fame and financial opportunity – first with the success of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring and later with the major art world appreciation for artists like Dondi, Lady Pink, Futura, Kaws, and, of course, Banksy.

T-Kid, Booze, by Henry Chalfant

Some graffiti writers might have preferred that the scene stayed closed to outsiders, and that the work stayed on train cars, bridges, and buildings instead of gallery walls. But socioeconomic and political changes would force artists to change and adapt in any case. The photography of Cooper and Chalfant not only preserved the heady early years of the scene, before the city transformed and gentrified the neighborhoods that fostered it, but they also helped provide publicity—and global recognition—for art that might have otherwise been lost to history. See more of their photographs from this period at the Bridges of Graffiti online exhibit.

Kell, Crash, by Henry Chalfant

Future, Break piece, by Martha Cooper

Ban 2, Deli, by Martha Cooper

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.