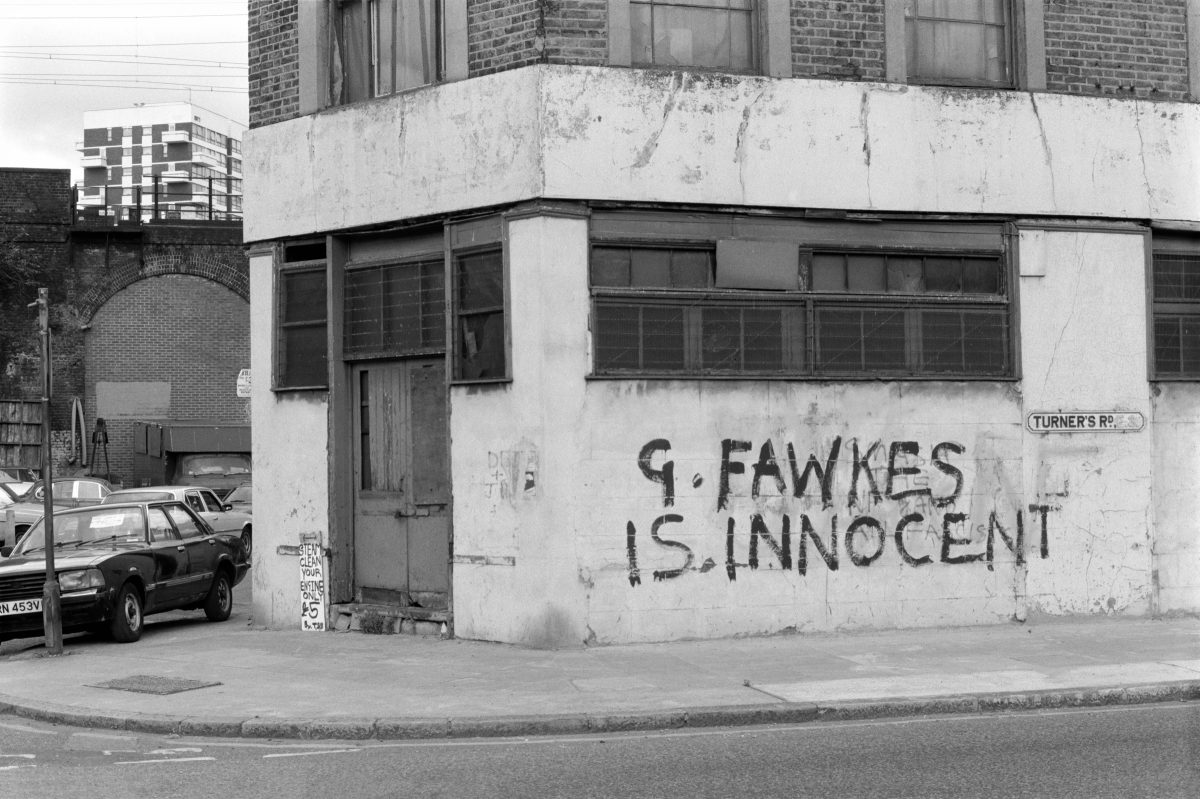

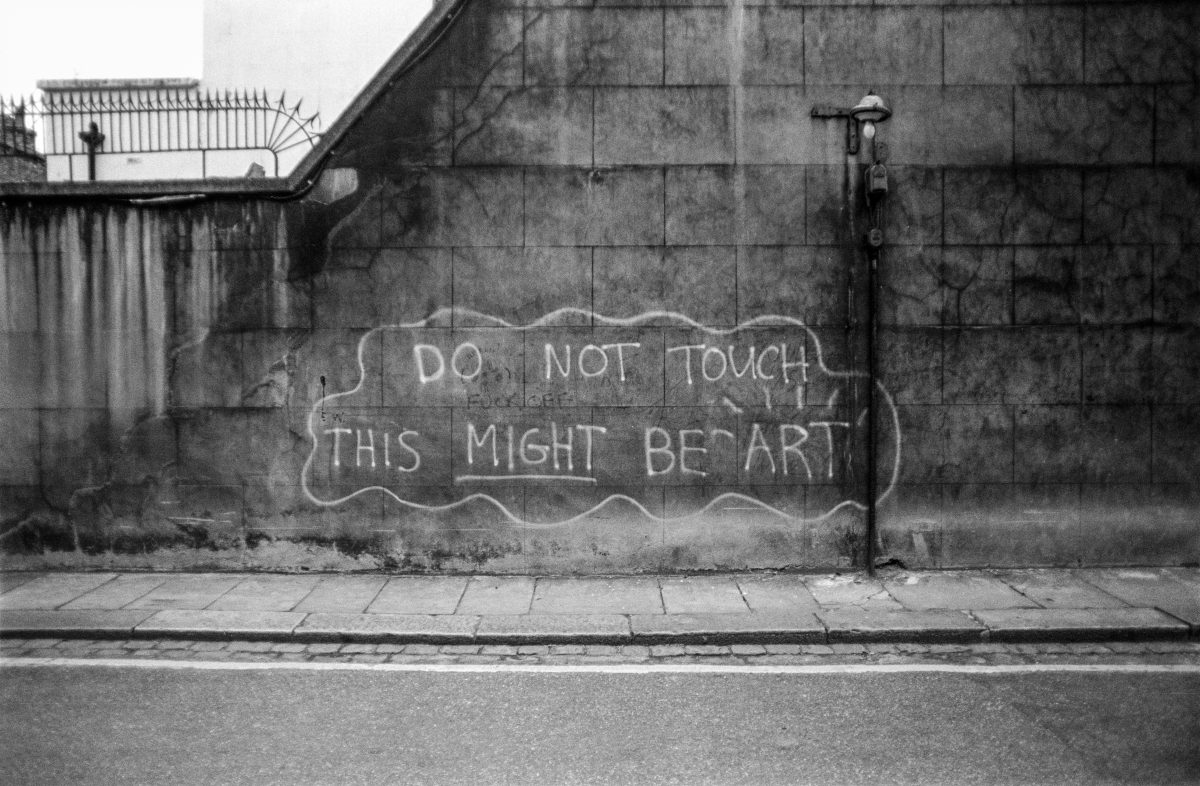

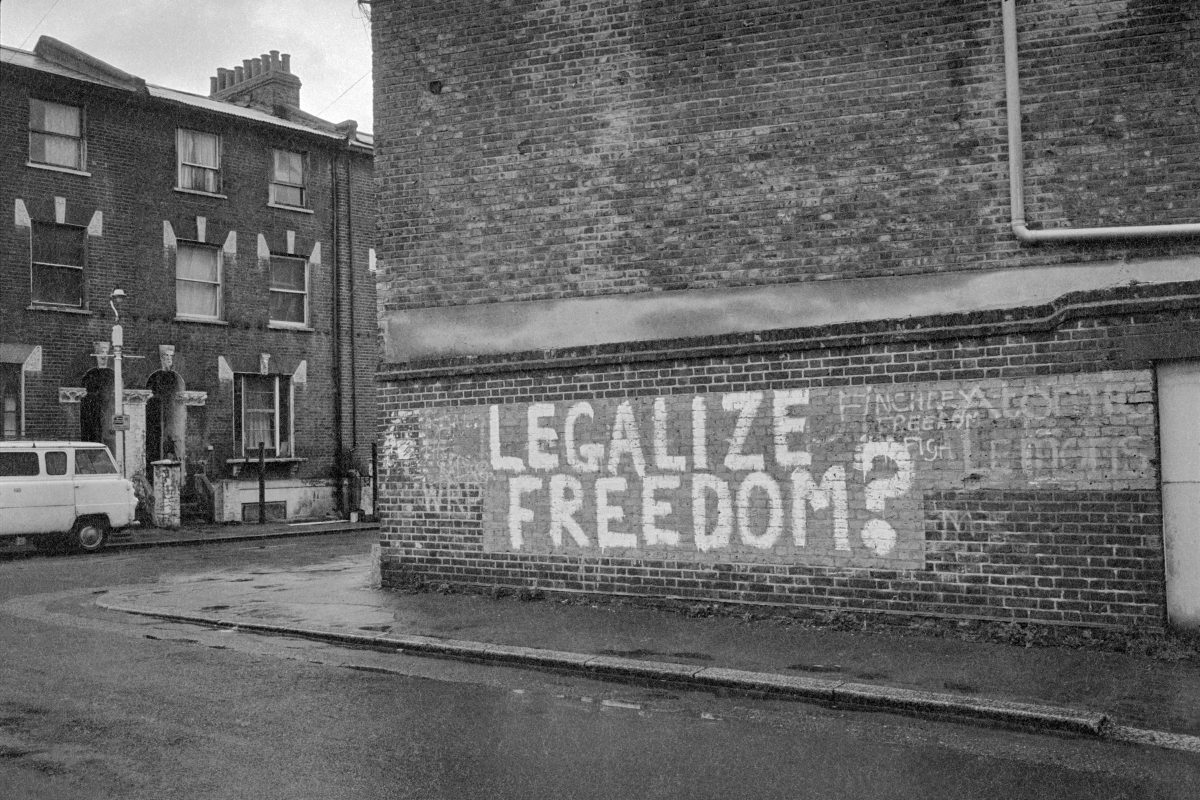

We feel when it’s gone. Sometimes we miss it. Not all of us take the time to walk about taking photographs of the everyday things we see but don’t notice. Peter Marshall did. His photographs of London in the 1980s show us a different time, before chain coffee bars, the ubiquitous world wide web, gentrification, gastropubs and a nation united under CCTV. They were no halcyon days to be sentimentalised, just different. Poverty then and poverty now. Racism was extrovert and confident. Things weren’t all that sophisticated then and they still aren’t. There were less vegans and skunk, and more bone-white dog poo. But London remains a city split by a river and ranked by class.

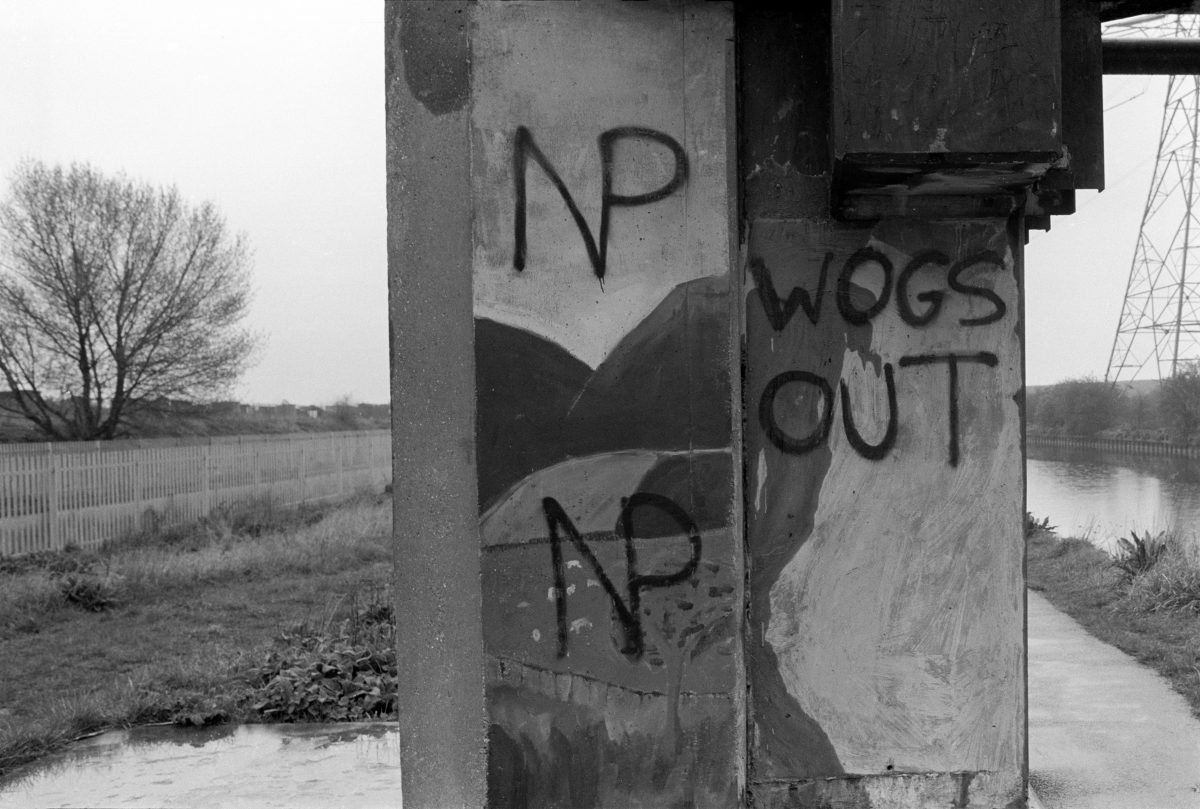

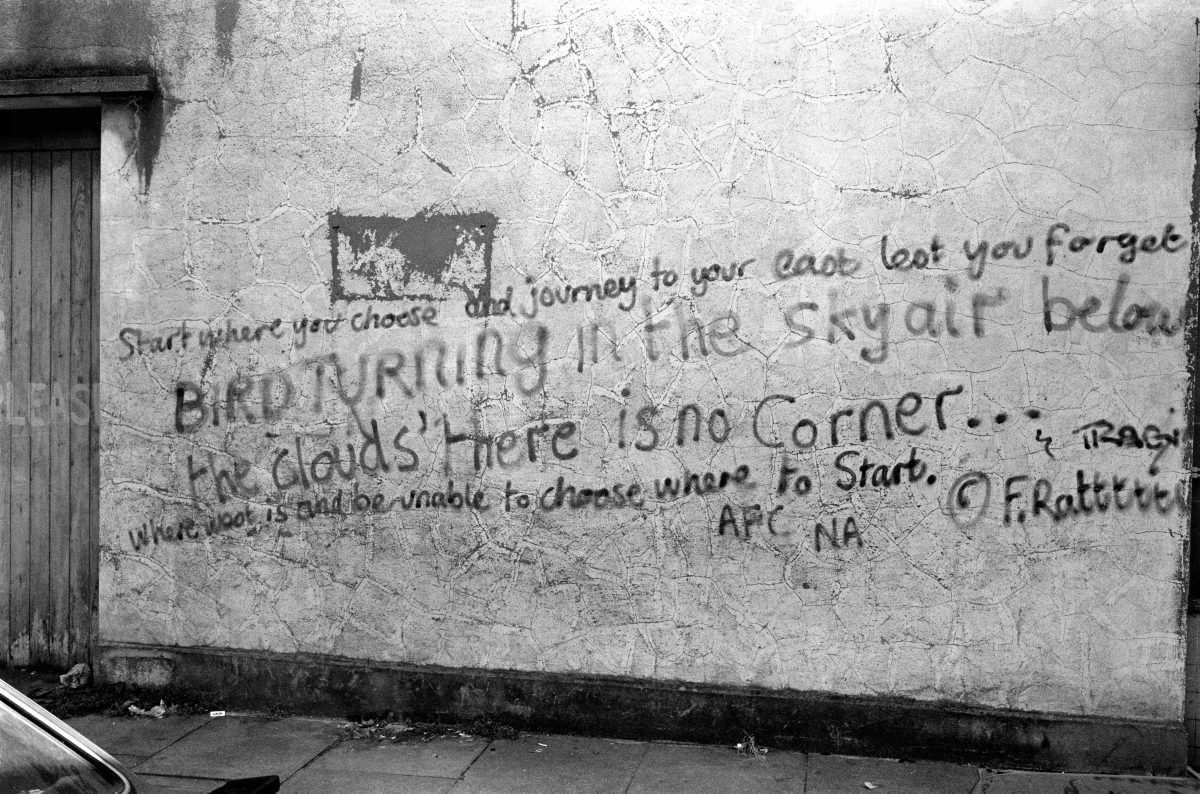

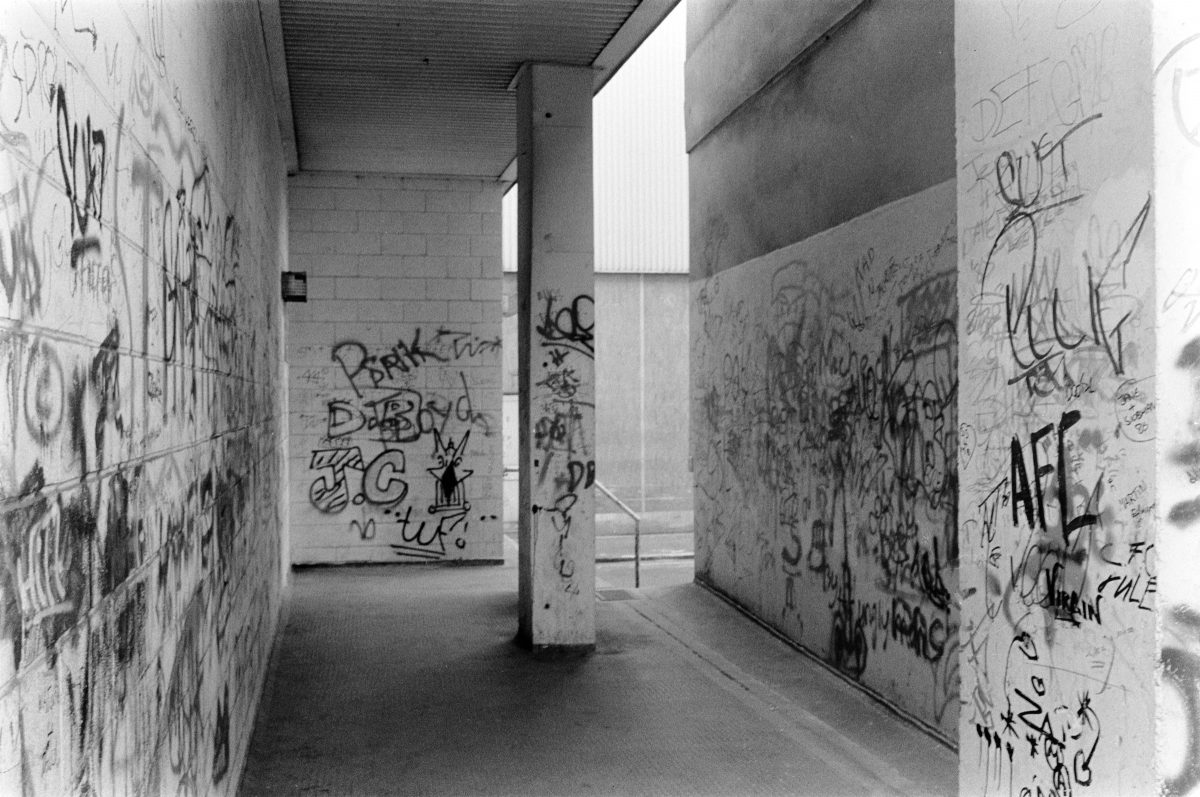

Peter took pictures of the buildings and streets in areas where Londoners actually lived, not the day trip hot spots and tourist mainstays. When people spoke, Peter saw their messages daubed on walls. We can see the graffiti for the far right National Front, that conjoined ‘NF’ that used to be pretty much everywhere and anywhere; poems on high rise experiments and neglected low-risers; orders and wit painted on walls that wasn’t removed because unless Her Majesty was in the area to open a little curtain and reveal a plaque stuck to a freshly painted wall no ‘VIP’ would ever see it and no craven local councillor wanting to impress the knob or knobesse would be bothered get it tarted up.

Peter’s London is authentic. This is what we saw.

Graffiti on container, King George V Dock, Newham, 1984

Intense congestion around the Royal Docks in the 1920s led to a new five part road scheme in the area which included both the Silvertown Way, a three-quarter mile long wide viaduct crossing a railway line and the entrance to the Tidal Basin high enough for shipping to pass below which opened in 1934, and the Silvertown By-pass, around one third of a mile of an elevated section with short bridges over several roads and a 109ft skewed bowstring arch crossing the railway to the Connaught Road Swing bridge, the cutting into the railway tunnel and Connaught Road itself.

The by-pass was opened without ceremony in 1935, closed in 1991 and demolished in 1995. I’m not clear why it was demolished, but possibly to facilitate either the construction of the DLR extension to London City Airport or the airport itself.

In the background is the CWS Flour Mill on Royal Victoria Dock.

– Peer Marshall

Webber St is a longish street that curves around from next to the Old Vic on The Cut to Great Suffolk St, and Hope Mission is still there, just a few yards to the east of the crossroads with Blackfriars Rd, its ground floor now rather different but still recognisable as Cafe DeNiro.

I suspect I took this picture on my way to buy photographic materials at Silverprint, which for some years was just a short walk away on the other side of Blackfriars Rd in Valentine Place.

Even closer and of photographic interest, next door on the right is a block of flats called ‘The Priory’ which now sports a blue plaque marking it as where Bert Hardy, (1913 – 1995), Picture Post’s best-known photographer, was born and grew up. A few years ago, walking behind a dragon on St Georges Day (as you do), I was able to point this out to the Mayor of Southwark and tell her something of the story of one of Southwark’s most famous sons – who she had never heard of.

The plaque was only put there in 2008, and although I knew he came from the area I wasn’t aware of the actual location when I made this picture. What attracted me was clearly the juxtaposition of the name ‘HOPE’ on the Mission and the National Front graffiti below and to the left on the Blackfriars Foundry wall, to which someone has added ‘= NAZI FILTH’ with a nicely dotted second I.

– Peter Marshall

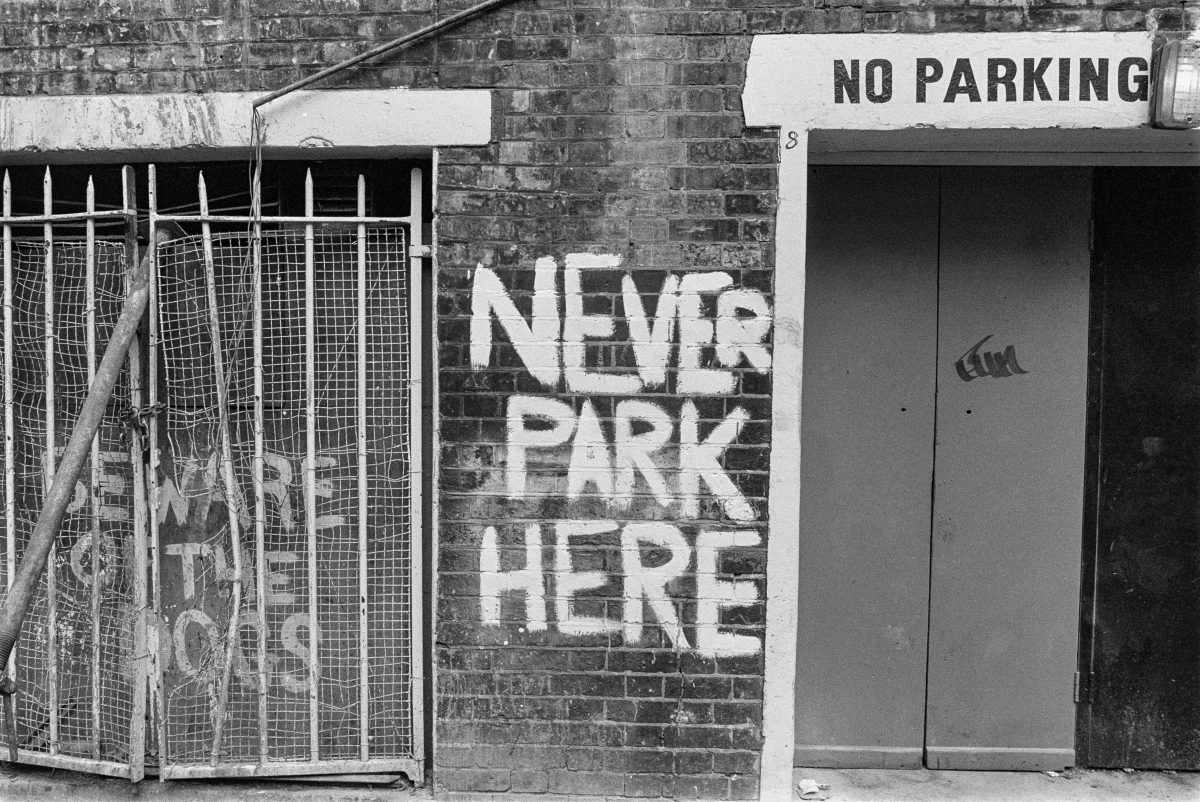

Never Park Here, Falconberg Mews, Soho, Westminster, 1987 87

Freedom Alley, Whitechapel High St, Aldgate, Tower Hamlets. 1980

Angel Alley or Freedom Alley is hard to find, an insignificant entrance between two shops on Whitechapel High St, immediately to the west of the Whitechapel gallery at the left of KFC.

Opposite the corner of the yard shown here is Freedom Bookshop, London and one of the world’s oldest anarchist publisher and bookshop, founded in 1886. It’s address is given as 84b Whitechapel High Street.

The shop has been attacked by right-wing arsonists on several occasions during its life, most recently in 2013, but remains open, and still selling, among many others, the works of Peter Kropotkin, 1842-1921, a Russian prince and geographer who gave up wealth and a privileged lifestyle to become the father of Russian anarchism.

– Peter Marshall

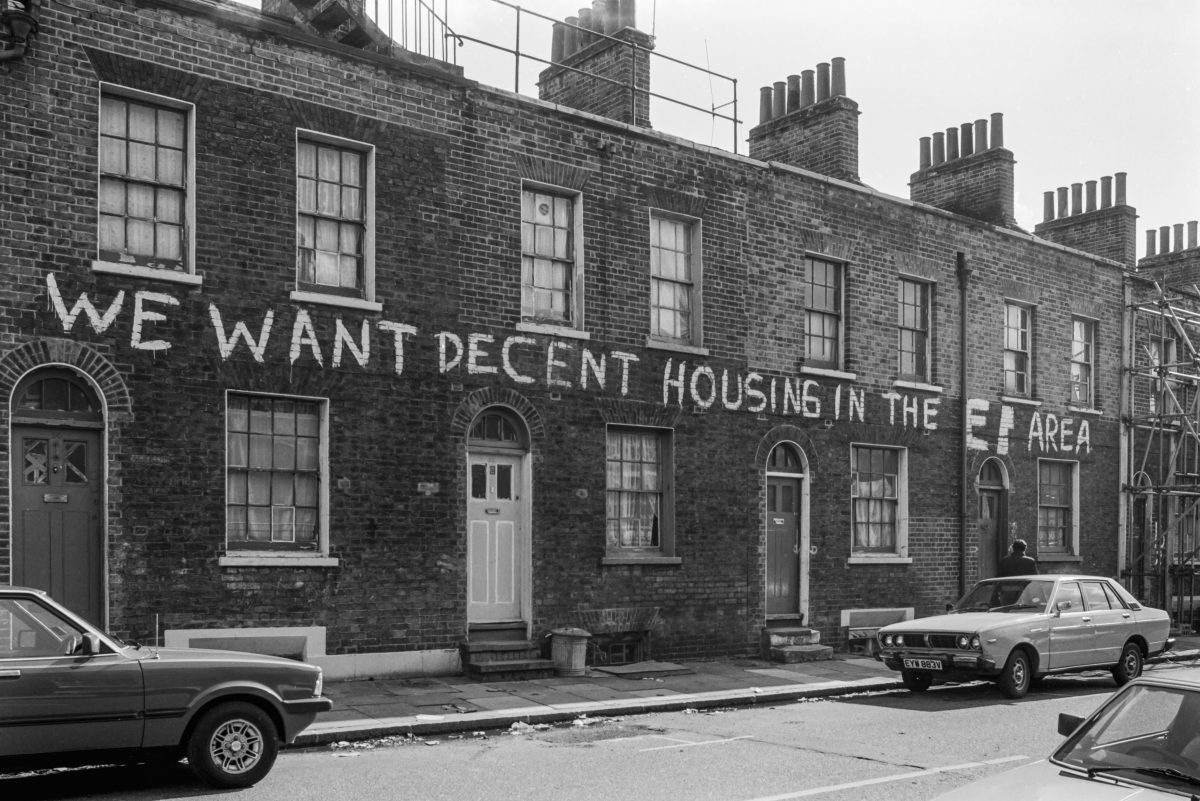

Varden St, Whitechapel, Tower Hamlets 1986

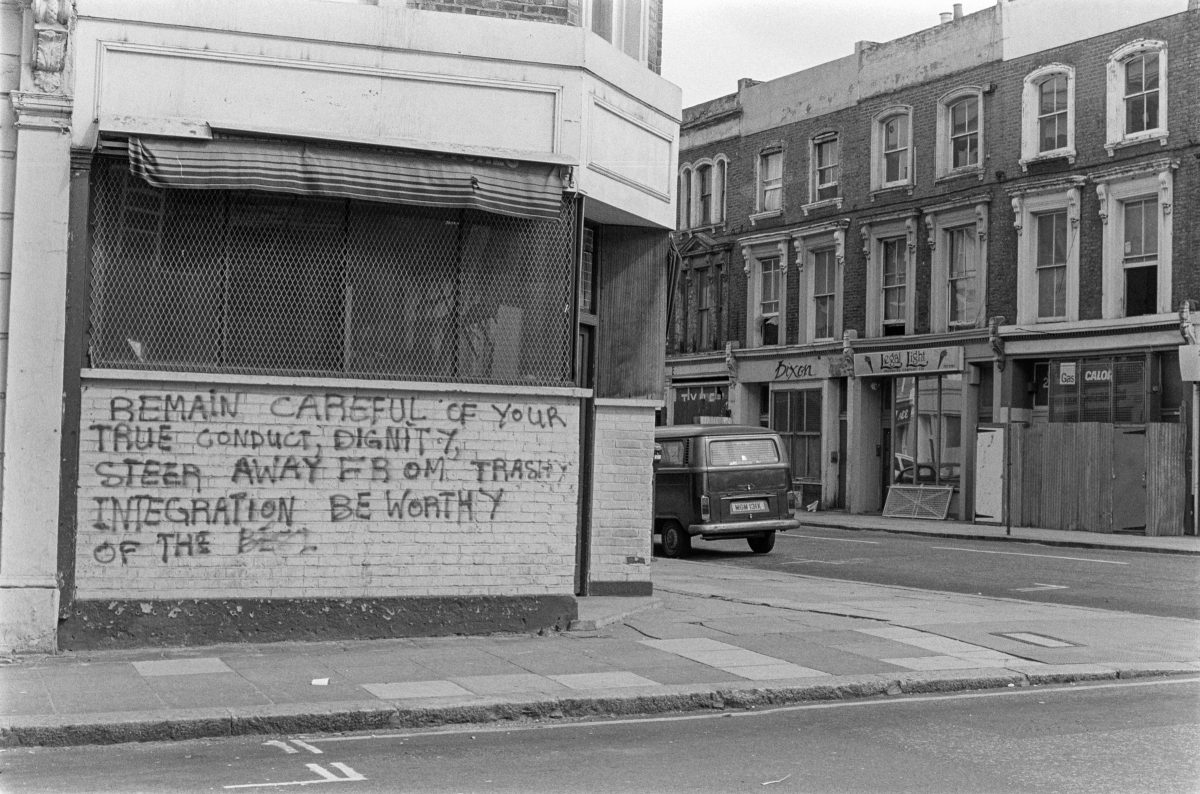

All Saints Rd, Notting Hill, Kensington & Chelsea, London – 1987

“REMAIN CAREFUL OF YOUR TRUE CONDUCT, DIGNITY, STEER AWAY FROM TRASHY INTEGRATION, BE WORTHY OF THE BEST”

Graffiti based on advice given given to the young Dr Martin Luther King: “Remain careful of your conduct. Steer away from ‘trashy’ preachers. Be worthy of the best.”

– Peter Marshall

Who could resist going to photograph Aristotle Road – and finding there this graffiti ‘Freedom With Anarchy’.

“Anarchism has but one infallible, unchangeable motto, “Freedom. Freedom to discover any truth, freedom to develop, to live naturally and fully” according to US anarchist, writer, labour organiser and IWW founder Lucy E Parsons (1853-1942), a remarkable woman who was probably born a slave, though she claimed only Native American and Mexican descent. Chicago police described her as “more dangerous than a thousand rioters…”

Books have been written about Aristotle’s concept of freedom, and according to the Oxford Handbook of Freedom he thought that “a person is free to the extent that he is able to live a life of politics and philosophy, and a polis is free to the extent that its institutions promote such a life for each and every citizen by removing the impediments to its realization”.

You can still recognise the location, just off Clapham High St, at the rear of Pearl Pharmacy though the balustrade, roof and stained glass have gone, the road name with its old S.W. is still on the wall. The car parked there back in 1980 was a little unusual, and is I think a T-Series Bentley. I thought at the time it looked a suitable motor for gangsters.

– Peter Marshall

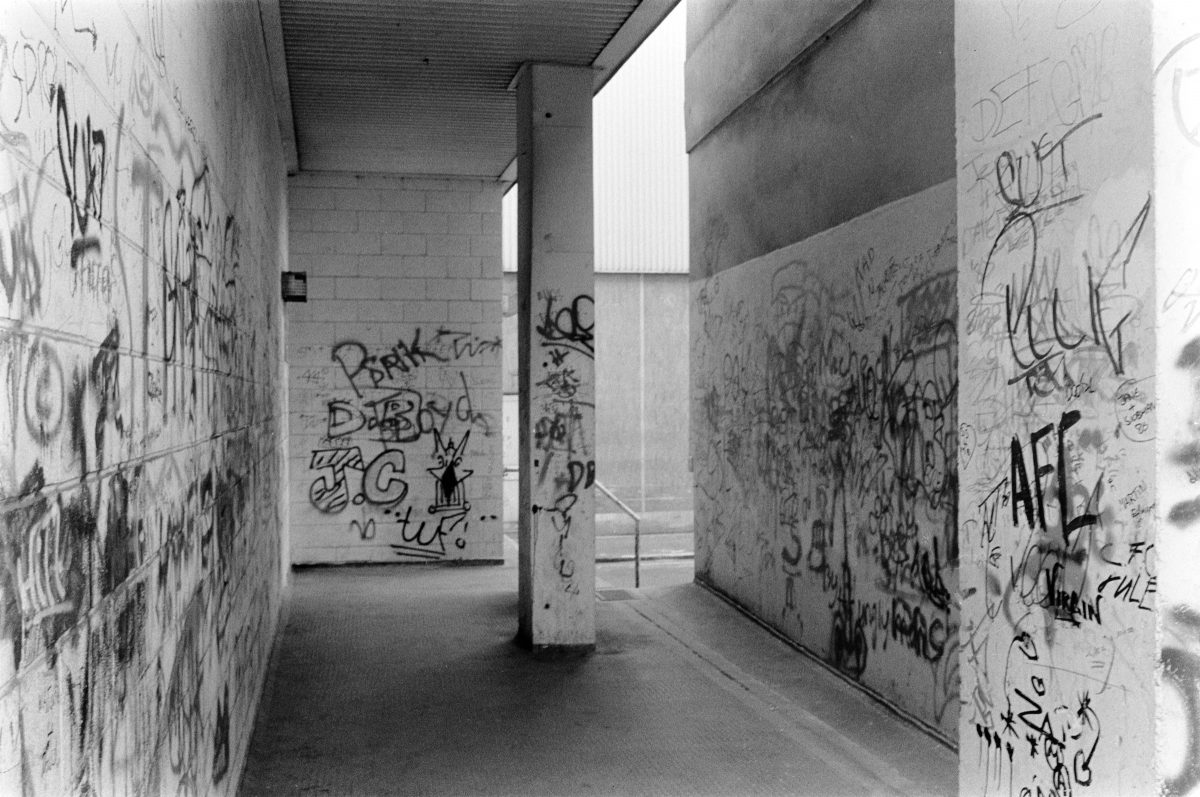

Limehouse, Tower Hamlets 86

Death to Fascism, Bus Shelter, Battersea, Wandsworth. 1980

I can’t at this remove remember why I was wandering around South London taking pictures with the Minox on a day in April 1980, but I’m fairly sure I had not gone out with the main intention of taking pictures, otherwise I would have picked up the Leica and possibly my Olympus OM-1. There must have been some other reason for my being there, and obviously having some time to spare. One possibility is that I had gone early and decided to walk from Queen’s Road Battersea to a meeting or exhibition at the Photo Co-op in Webbs Road in Clapham, which had started the previous year, rather than take the shorter walk from Clapham Junction.

As usual at the time I have no record of exactly where I was, and this street is fairly typical of many of the wider streets in the area, with its late Victorian housing. Only the main roads are this wide and have a pavement where I could get back far enough to make a picture like this with the 35mm lens.

I suspect I will have waited some time, not for the bus, but for people at the bus stop to arrange themselves rather better in the frames provided, but with little luck, and I think made this exposure as the bus the bus was about to arrive, knowing they would board.

Obviously it was the graffiti that attracted my attention. The large white letters of ‘DEATH TO FASCISM’ are easy to read in this small image but the smaller black ‘Kill A BLACK TODAY’ is perhaps harder to read.

– Peter Marshall

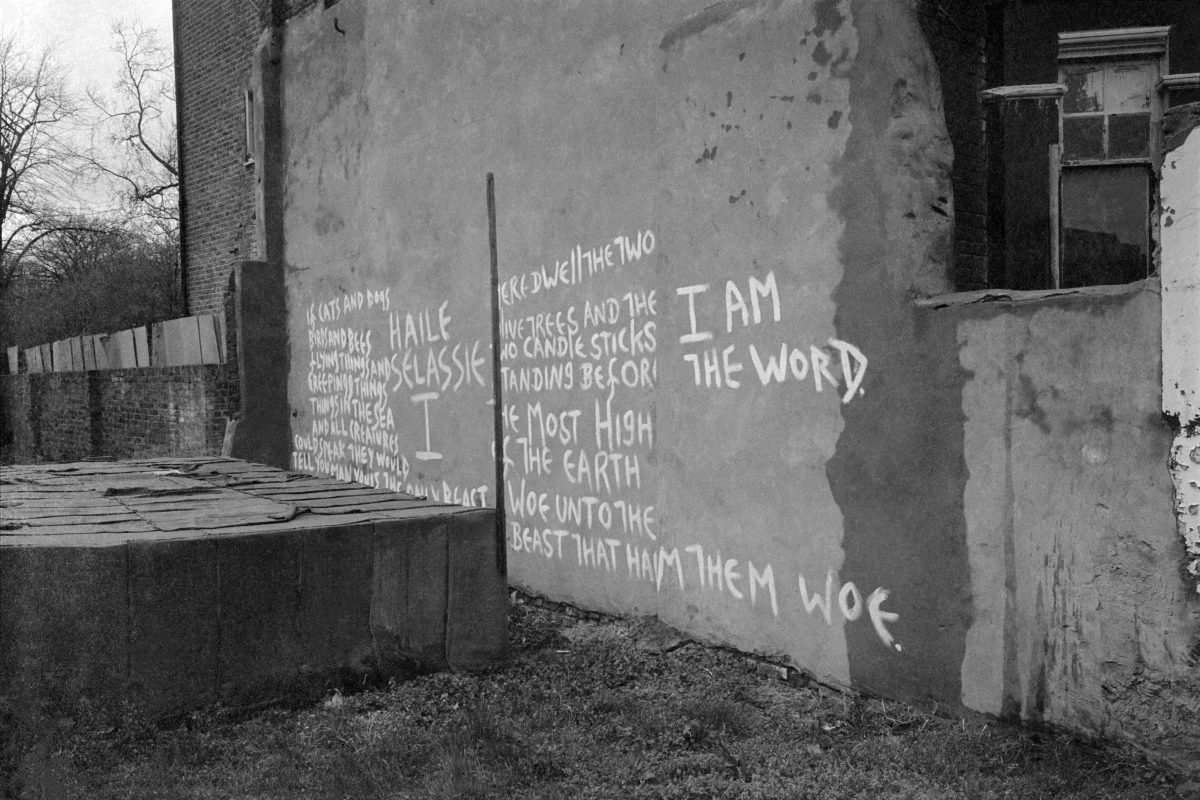

“If Cats and Dogs

Birds and Bees

Flying Things and

Creeping Things

Things In The Sea

And All Creatures

Could Speak They Would

Tell You Man You Is The Only Beast

Here Dwell The Two

Olive Trees And The

Two Candlesticks

Standing Before

The Most High

Of The Earth

Woe Unto The

Beast That Harm Them Woe

Haile Selassie I

I Am The Word”

28-34 St. Agnes Place, Kennington, SE11 was occupied by various Rastafarian groups for over 30 years. First squatted in 1969, it became the longest continually squatted street in London it was finally cleared of most residents in 2005, but the Rastafri temple remained for another 18 months.

I often visited the street when I was visiting friends in a council flat just across the road where we went most months and had a short stroll in the park on a Sunday afternoon, but I don’t recall ever seeing anyone on the street and there are no people in any of my pictures taken here.

– Peter Marshall

Prefab, Poplar or Limehouse, Tower Hamlets. 1982′

I think this was the one remaining structure in what had once been a small estate of pre-fabs and was clearly now a site for fly-tipping. The message on the building wall is dated 23/4/80 and I took this picture in February 1982; I’m not sure it was still inhabited, though the two cars parked there (one almost hidden behind), what appear to be blankets on a washing line at left suggest it was, but those bins seem to be in front of a boarded up door. I can’t decide looking at the mini if it has a missing wheel or is simply parked on very uneven ground, but otherwise it looks in good condition with no broken windows. There were people living here a couple of years later.

Strictly I think this is not a prefab, but an LCC Mobile Home which were put up to deal with the housing shortage in the 1960s.

– Peter Marshall

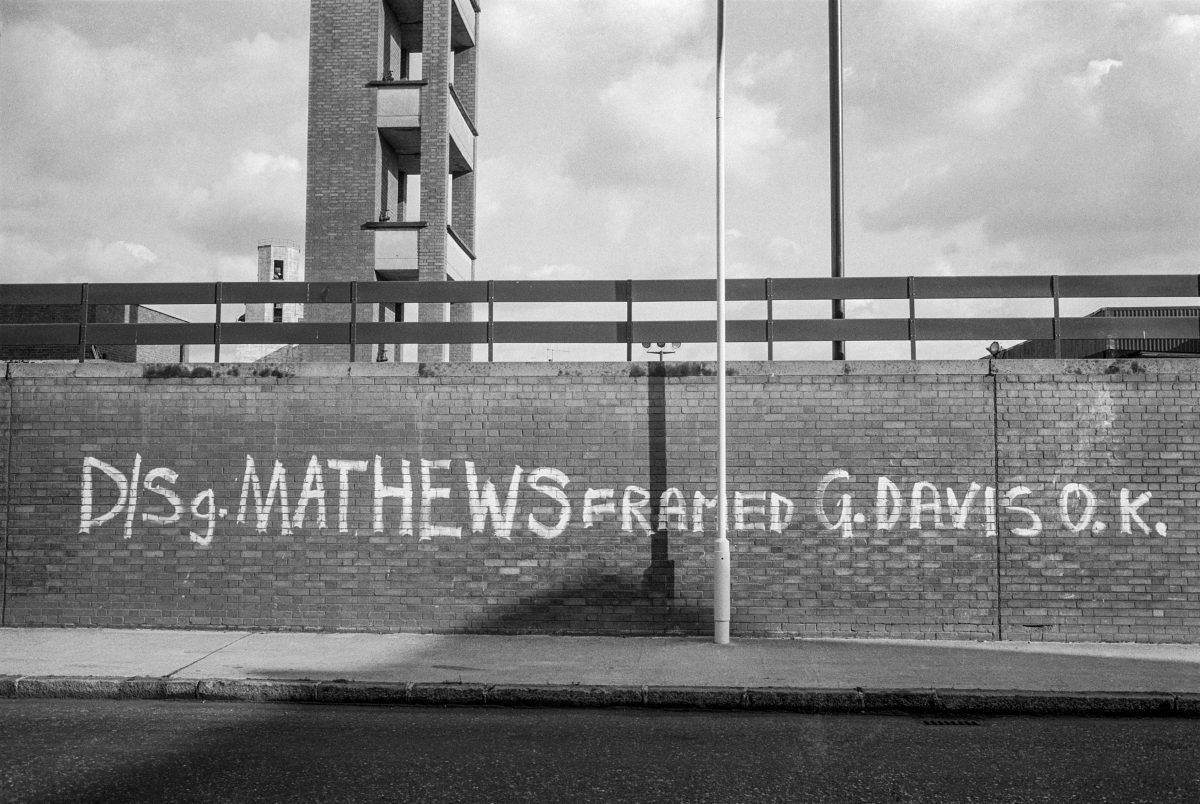

Fire Station and Graffiti, Fort St, Silvertown, Newham. 1983

Fire Station and Graffiti, Fort St, Silvertown, Newham. 1983:

The wall, fire station tower and Pontoon Dock silo and the two posts can still be seen on Fort St, though the fence on top of the wall is now solid, and the graffiti has long been scrubbed out.

George Davis for once in his life was innocent, and 36 years after his conviction in 1974 for robbery of the London Electricity Board in Ilford a court finally quashed his conviction, though saying “We do not know whether Davis was guilty or not, but his conviction cannot be said to be safe.” But for anyone requiring less cast-iron legal standards of truth it is transparently obvious that D/Sg Matthews had framed him for the job, provoking a mass campaign that graffitied walls and dug up the Oval cricket pitch. It was clear enough at the time and in 1976 Davis was released from his 20-year prisons sentence under royal prerogative, only to be caught red-handed the following year on a bank job for which he had little choice but to plead guilty.

– Peter Marshall

Burne St, Lisson Grove, Westminster, 1987

Fence with NF graffiti, Wandsworth. 1980

Some effort has been made to make the corrugated iron fencing more attractive by painting it in two colours. I can’t read the fly posted notices, which do appear to have a radioactive hazard symbol on them but the National Front graffiti is clear and was unfortunately common across London at this time.

I’m not sure exactly where this was taken, although the wall behind the fence is fairly distinctive, as are the steeple and flats at right. It was probably on or close to Vicarage Crescent or Lombard Rd.

– Peter Marshall

St Agnes Place, Kennington. 1980

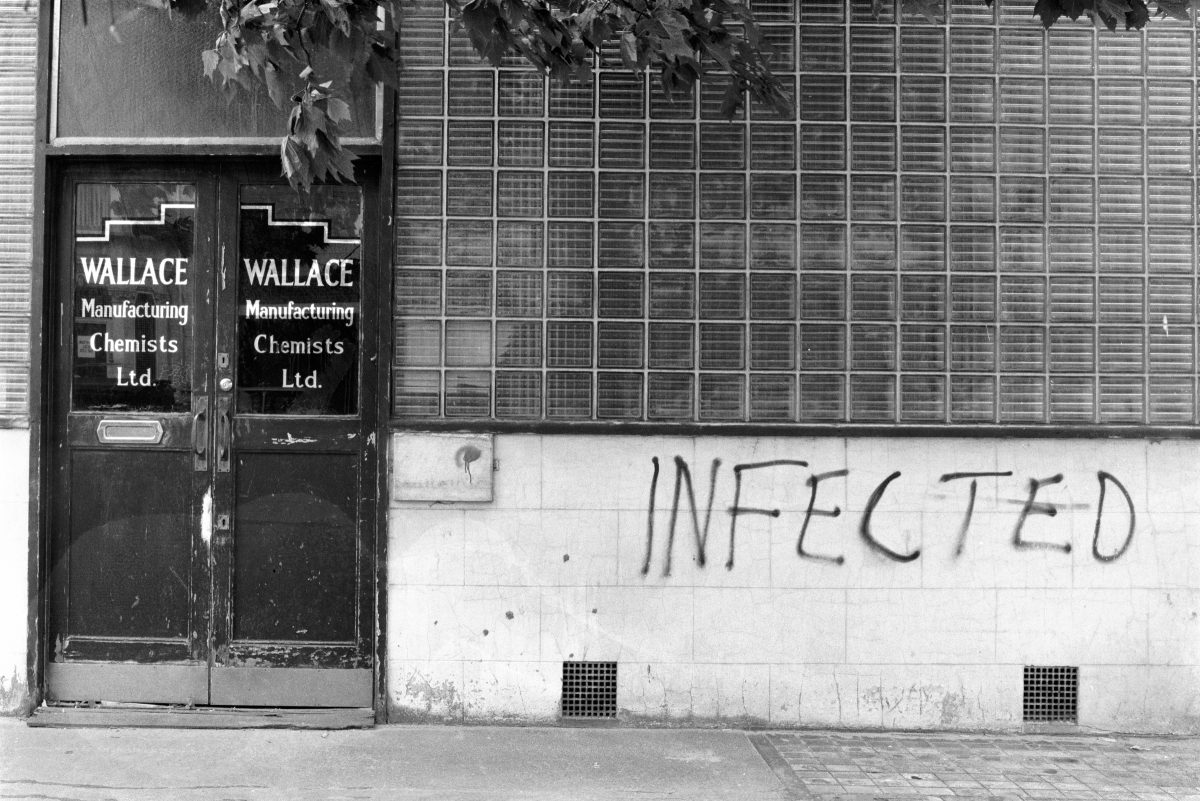

Wallace, chemists, Infected, graffiti, Netherwood St, Kilburn, Camden, 1998

Lea Navigation, Tottenham, 1983

St Agnes Place, Kennington. 1980 London

Limehouse, Tower Hamlets 1984

Lovell’s Wharf, Greenwich. 1983

St Leonard’s Rd, Bright St, Poplar, Tower Hamlets, 1988

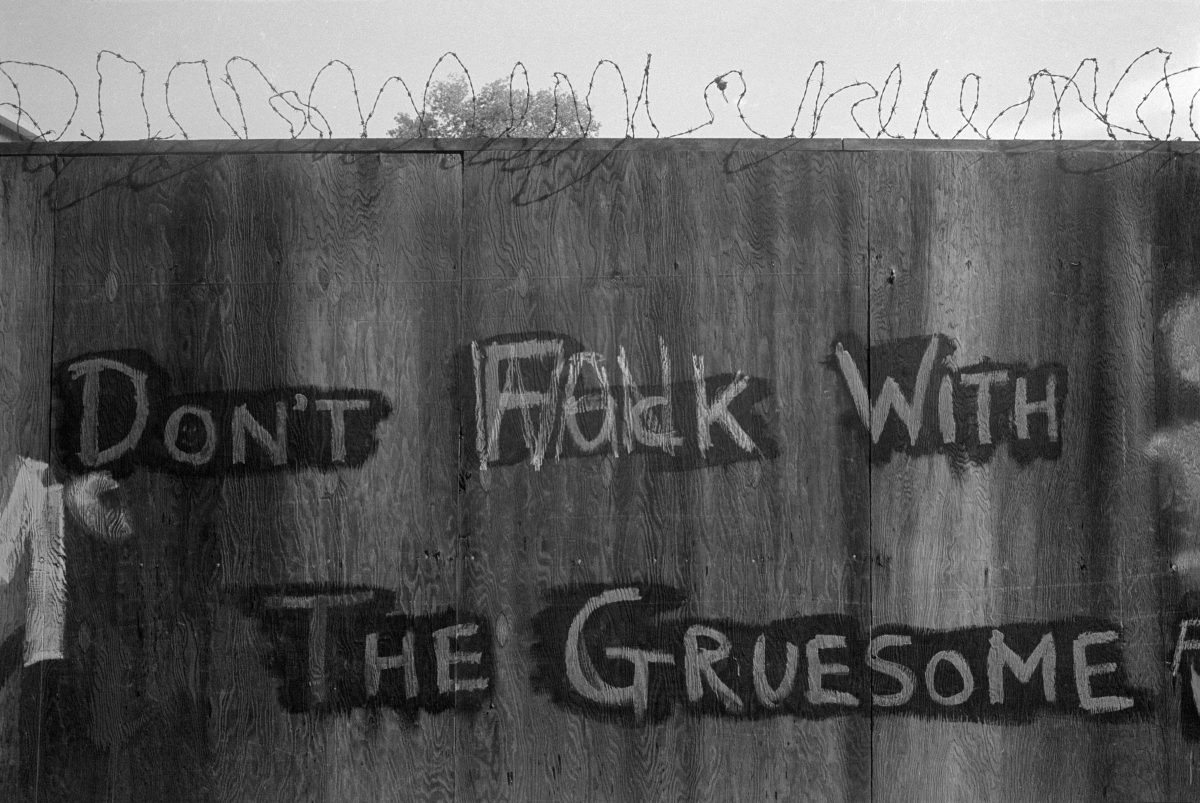

The Gruesome Clapton, Hackney, 1982

Graffiti, Green Lanes, Highbury, , Islington / Hackney, 1988

The Gruesome Clapton, Hackney, 1982

Burne St, Lisson Grove, Westminster, 1987

Via: Peter Marshall.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.