The plain fact that the American war in Vietnam was a mistake and a crime – because it was undertaken so lightly, pursued so brutally and abandoned so perfidiously – is about the only plain fact there is.

—Martin Woollacott

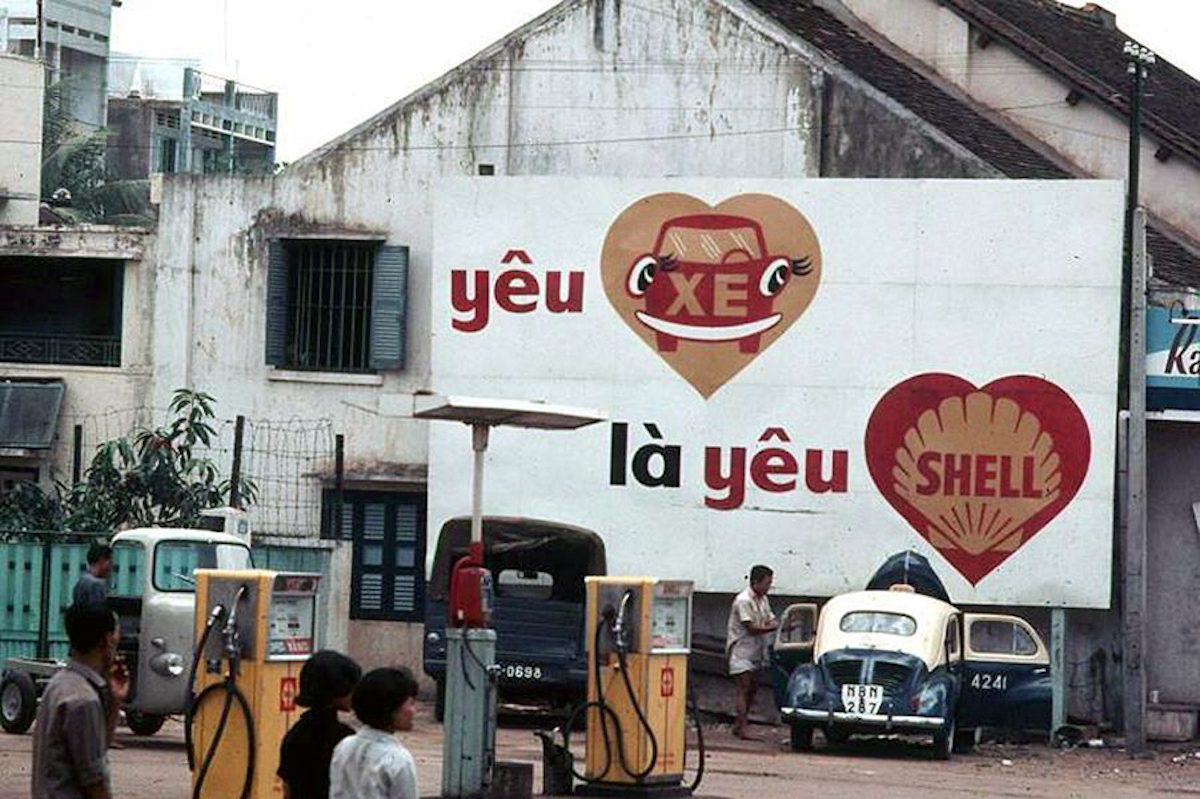

Perceptions of Saigon were long dominated in the West by the horror of the infamous execution photo and the desperate images from the end of April 1975, when U.S. forces finally evacuated the country and the North Vietnamese moved in to claim the capital. In these photographs, Saigon’s civilian residents cling to the fleeing American marines and journalists, terrified of what awaits them once the enemy takes over. The photos are extraordinary, and not in any way representative of Saigon during the majority of the war.

Whether Vietnam’s occupiers were French or American, they were not wanted. The Vietnamese struggled for centuries to escape colonial status, and by the 1960s, their patience for invaders of every kind had worn seriously thin. In 1968, at the start of the Tet Offensive, Fernand Gigon, a Swiss journalist working in Vietnam, documented “a general hatred toward Americans” in Saigon. “Three, four, perhaps five percent of the population claim to be delighted with their presence. And the others? From the bar hostess to the secretary of a minister, by way of the rickshaw coolie and the administration typist, all, unanimously, revile the occupant and try to take advantage of him.

At no time do they believe he’s fighting for their ‘freedom to choose their way of life’ as the made in U.S.A. propaganda tells it.

A rickshaw driver, hearing me speak French, tapped me on the shoulder and pointed to a group of American soldiers standing on the sidewalk: “Not nice, Americans, only know how to bang-bang on Vietnamese.” And from his perch on the rickshaw’s saddle he imitated a G.I. firing his automatic rifle.

A bar girl explained to me: “Luckily they’re drunk when we go out with them: they don’t know what they’re doing.”

A highly-placed bureaucrat: “With our 5000 piasters per month, we’re just able not to starve to death: before the Americans, life was less expensive”…

All day long, the same complaints, borne of contempt and resentment. This hatred hasn’t yet changed to aggressiveness, but is real enough to make life miserable. Soldiers on leave from the base at Bien Hoa aren’t allowed to go to Saigon except in small groups. A Vietnamese told me: “Whether one or two battalions arrive at the same time a fight breaks out: no one knows when or where it will stop.”

Any excuse, any provocation can cause bloodshed.

Some American GIs, disgusted with the treatment of the Vietnamese, defected, left their units, and settled permanently in the city. Black soldiers found refuge from the racism in their units at “Soul Alley,” a “string of bars, clubs, shops and eateries that thrived in US-occupied Saigon,” reports PRI. Located near the Tan Son Nhut Air Base, which is now defunct, the bars and restaurants there went out of their way to cater to Black GIs missing home. But there, too, soldiers were exploited by locals and exploited them in turn, fathering children who suffered tremendously “once Vietnam was reunited and the Americans were driven out.” Some veterans, like Paul Blizard—who has documented the city for years in “before and after” photos—returned decades later to make amends.

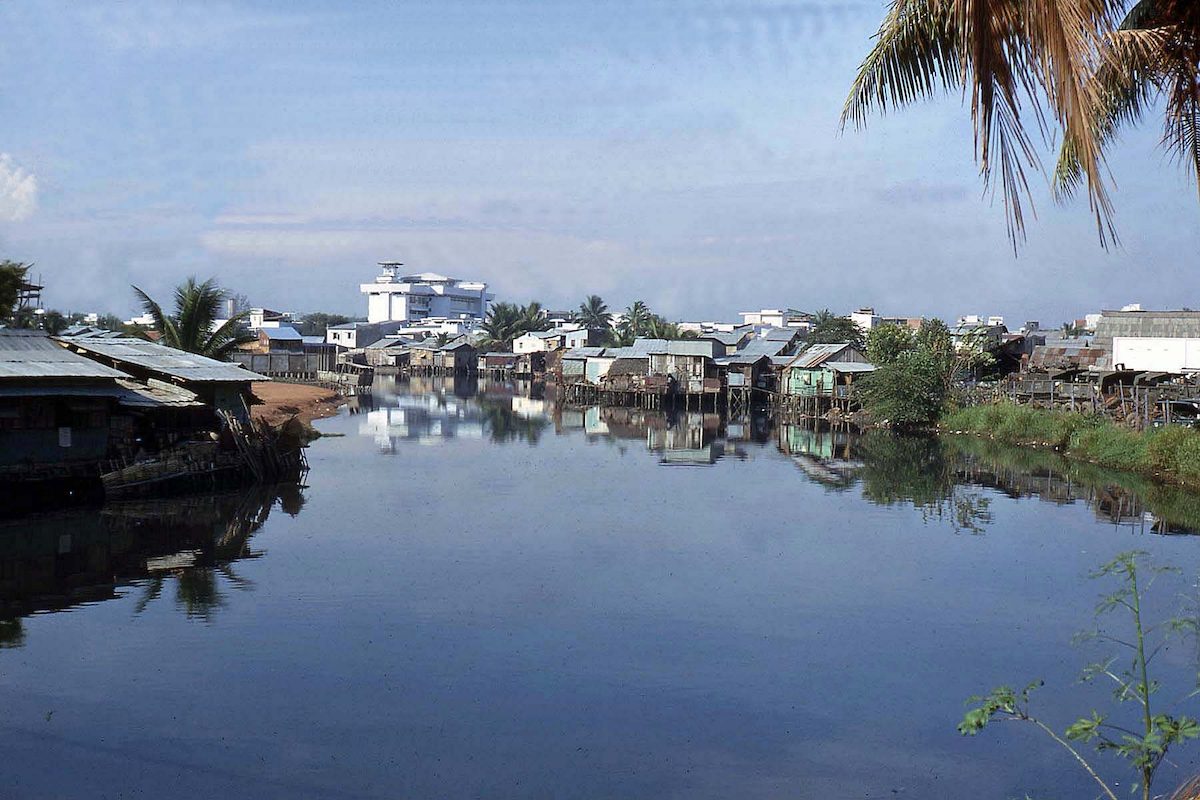

For most ordinary South Vietnamese in Saigon throughout the war, life went on as it had it before. “Through all the years of conflict,” writes The Guardian’s Martin Woollacott, “war had not often touched Saigon, with the exceptions of the occasional rocket attack, some restaurant bombings and the dramatic but limited incursion into the city” during the Tet Offensive and short-lived Battle of Saigon. Modern Vietnamese fashions filled the streets. The city’s daily business continued. In the photos here from the late sixties, we can see the odd reminder that a war rages on multiple battlefronts outside the city—a few armed South Vietnamese soldiers here and there. But for the most part, we see a city bravely enduring yet another unwanted occupation by another Western power intent on using the region for its own designs, largely indifferent to the welfare of its people.

via Saigoneer/The Culture Trip

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.