For almost 20 years after the Second World War a few London property developers, often acting in collusion with London County Council (LCC), drastically changed the capital’s skyline forever. Traffic was a huge concern for the city’s post-war planners and this coincided with a voracious and almost insatiable demand for office space. So while buildings got higher, which meant more rent and profit per acre, and more prestige for the architects, the roads got wider.

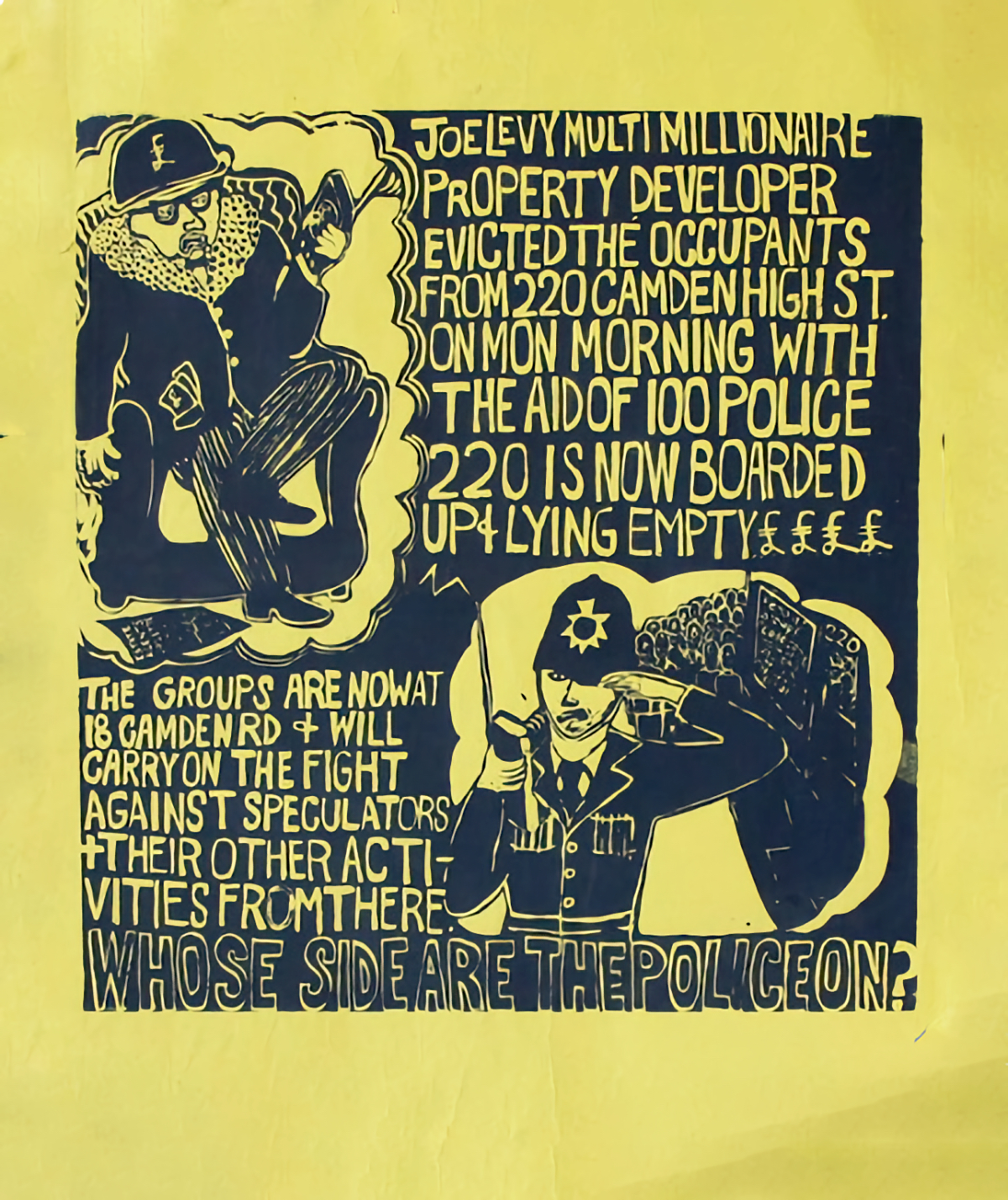

In 1952 the developer Joseph Levy, a 46-year-old bookmaker’s son from Acton, acquired planning permission for a site on the north side of the Euston Road and west of Hampstead Road. Four years later the LCC wanted to widen the Euston Road at about the same point and Levy had them over a barrel. Secretly he had been buying parcels of property along the north side of the road and a relatively impoverished LCC was forced into a secret deal. Levy would give the council the land needed to widen their road while in return they would give planning permission to build the massive Euston Centre. This meant the subsequent demolition of run-down Victorian terraces and the old Seaton Street market or as Levy described the area, “a derelict bloody den of disease.”

To nobody’s great surprise the widened Euston Road, which included an underpass at the junction of Tottenham Court Road, remained a traffic black spot. Vehicles, especially taxis, continued to use the parallel Warren Street as a rat run. In 2013 Camden Council put to a stop to this by permanently closing part of the street to through traffic. Closing a road to traffic in central London is hardly unusual these days but in this case there was a certain irony. For much of the 20th century Warren Street had been the centre of the used-car trade in London and was the oldest street car market anywhere in Britain.

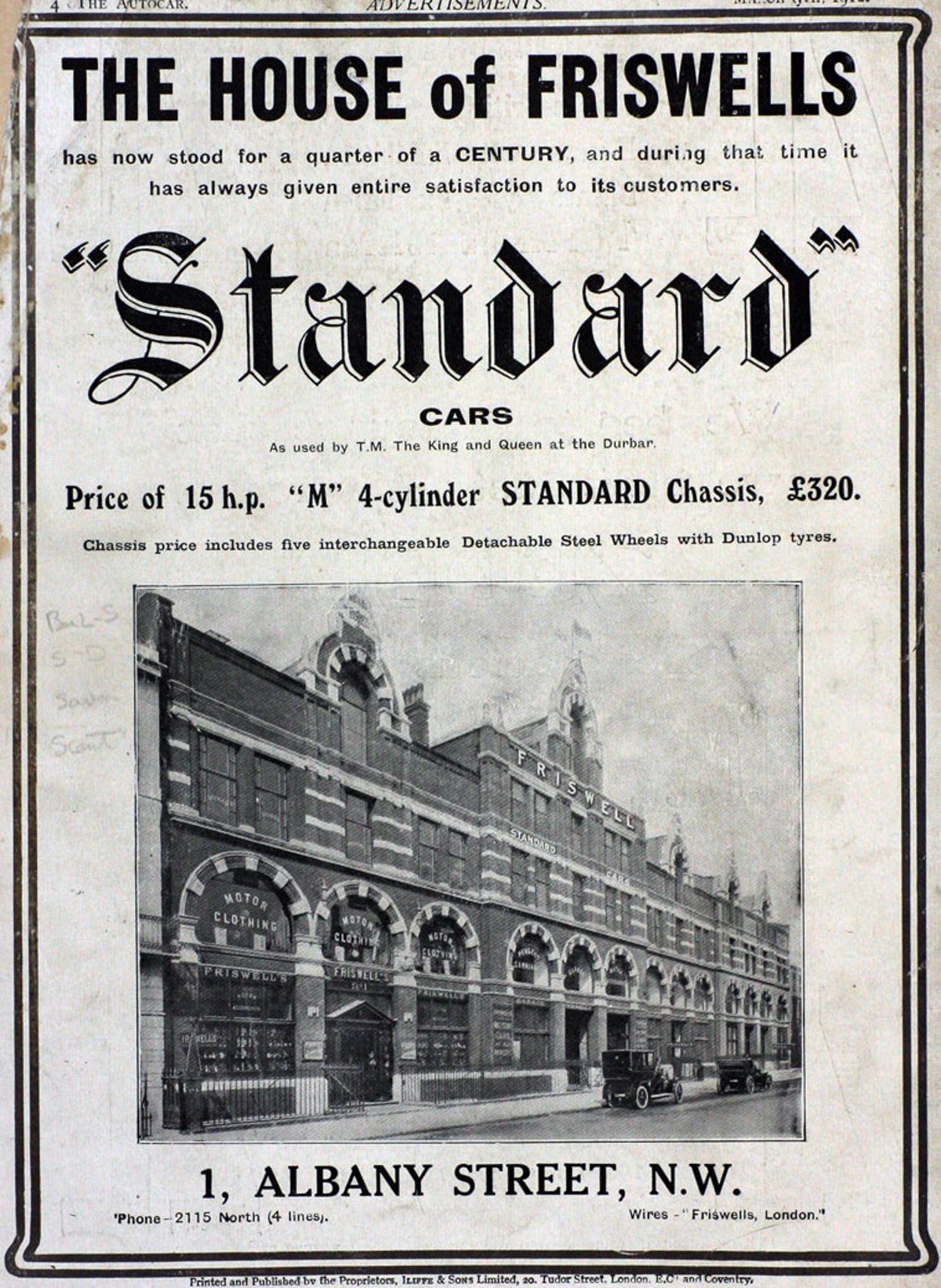

It all started in 1902 when Charles Friswell, an ex-racing cyclist and successful engineer, astutely hopped on the running board of a new burgeoning car industry and opened the massive ‘Friswell’s Automobile Palace’ at 1 Albany Street on the corner of the Euston Road. It was a huge success and soon other dealers started to open along the Euston Road and subsequently on the quieter Warren Street. The main dealerships were soon joined by ‘small fry’ or ‘pavement dealers’ – men who bought and sold cars of questionable origin on street corners and in cafés, milk bars and pubs. After the Second World War, when new cars were almost impossible to come by, the Warren Street market grew even bigger. Bernie Ecclestone began his career among the spivs and hustlers there, as did Alan Clark, the infamous philanderer and diarist, who knew plenty of well-off graduates who had a few quid to spend on a second-hand vehicle.

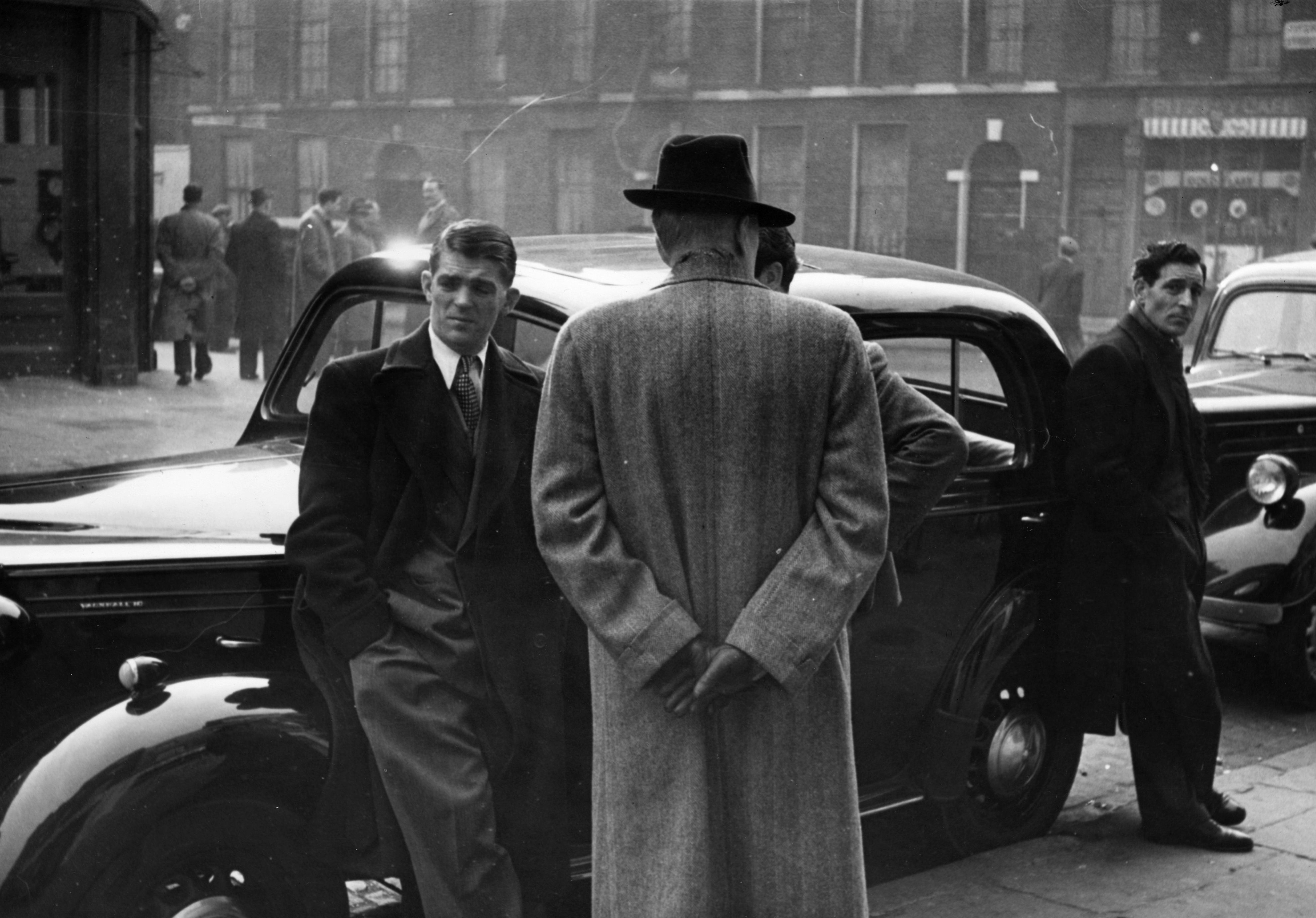

19th November 1949: Car dealers of Warren St, London discuss business. Original Publication: Picture Post – 4925 – Car Dealers Of Warren Street – pub. 1949 (Photo by Charles Hewitt/Picture Post/Getty Images)

In December 1949 the magazine Picture Post visited Warren Street and feigned shock at the numerous cash deals taking place: ‘Bundles of dirty notes were going across without counting… there is nothing illegal about a cash sale unless, of course, thieves fall out and pick each other’s pockets.’

The word ‘spiv’ is not often used these days but after the Second World War, however, the word was almost ubiquitous. It was used to describe the smartly dressed black marketeers who in a time of controls and restrictions lived by their wits, buying and selling ration coupons and sought-after luxuries.

The exact origin of the word is lost in the London smog of thieves’ slang but has been used by London’s criminal fraternity since the 19th century. It meant a small-time crook or con man rather than a full-time and dangerous villain. In the Cassell Dictionary of Slang, Jonathan Green suggests the word originally came from the Romany ‘spiv’, which meant a sparrow and was used by gypsies as a derogatory reference to those who picked up the leavings of their betters, criminal or legitimate.

Even the law-abiding amongst the public during and after the war appreciated these small-time criminals who wore flashy suits with wide lapels and bright ties. Without the spivs and the black market it was almost impossible to have any quality of life at all and after the war the spivs became even more prevalent as the restrictions and rationing became even more extreme.

It was rationing that gave spivs a reason to exist and during the general election of 1950 the Conservative Party actively campaigned on a manifesto to end rationing as soon as possible. The issuing of petrol coupons ended in May 1951, while sugar rationing finished two years later. Finally, in 1954 the public were allowed to buy meat wherever and whenever they wanted which meant the end of all rationing completely and the proper era of the spiv had essentially come to an end.

The last day of Seaton Market in Hampstead Road near Euston 80 year old Harry Gibber had traded there for 52 years

One could hardly describe Joe Levy, an extraordinarily rich man, as a spiv and a sparrow picking up scraps, although essentially that is how he ended up owning much of the land that enabled him to build the Euston Centre. It took almost 400 separate property deals (made secretly to avoid the price inflating) to enable Levy to make his plans a reality, the last of which was completed in 1963. At the end just one property owner was holding out to Levy and was in a position to ruin the whole of the carefully constructed project. One cold morning Joe Levy decided to go and talk to the man himself and offered £50,000. The man eventually agreed, as long as it was cash, and Levy asked him if the money had made him a happy man. The man said it made him very happy to which Levy said, “Now I’m going to tell you something that will make you very unhappy. I needed your house so badly I might have paid you a quarter of a million pounds for it.”

It wasn’t until 1964 that the deal between Joe Levy and the LCC became publicly known but by then it was too late. Demolition for the site was already underway. The massive Euston development became the single most profitable office development in the world. In November of that year the new Labour government imposed a ban on new office development in and around London which meant, in Levy’s words, property development was “no longer as easy as shelling peas”. By then, however, Levy along with developers such as Harold Samuel, Charles Clore, Jack Cotton and Charles Forte, had changed London forever.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.