“We plunged ahead in awe of what we witnessed. Many layers of meaning were preserved on negatives which otherwise might never have seen the light of day. It makes the present seem so much sweeter.”

– John Cohen

It’s easy to look at John Cohen’s incredible career as a photographer, filmmaker, educator, and musician and see something of a caricature of the middle-class New York folkie striving for old-time authenticity – like some of the characters in Christopher Guest’s good-natured mocumentary A Mighty Wind (no doubt inspired by Cohen himself). In a superficial sense, this actually is Cohen’s story, or one of many stories in the extraordinary life he lived, which also informed another film about the folk era, the Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis, in which Cohen appears with his last band, the Down Hill Strugglers.

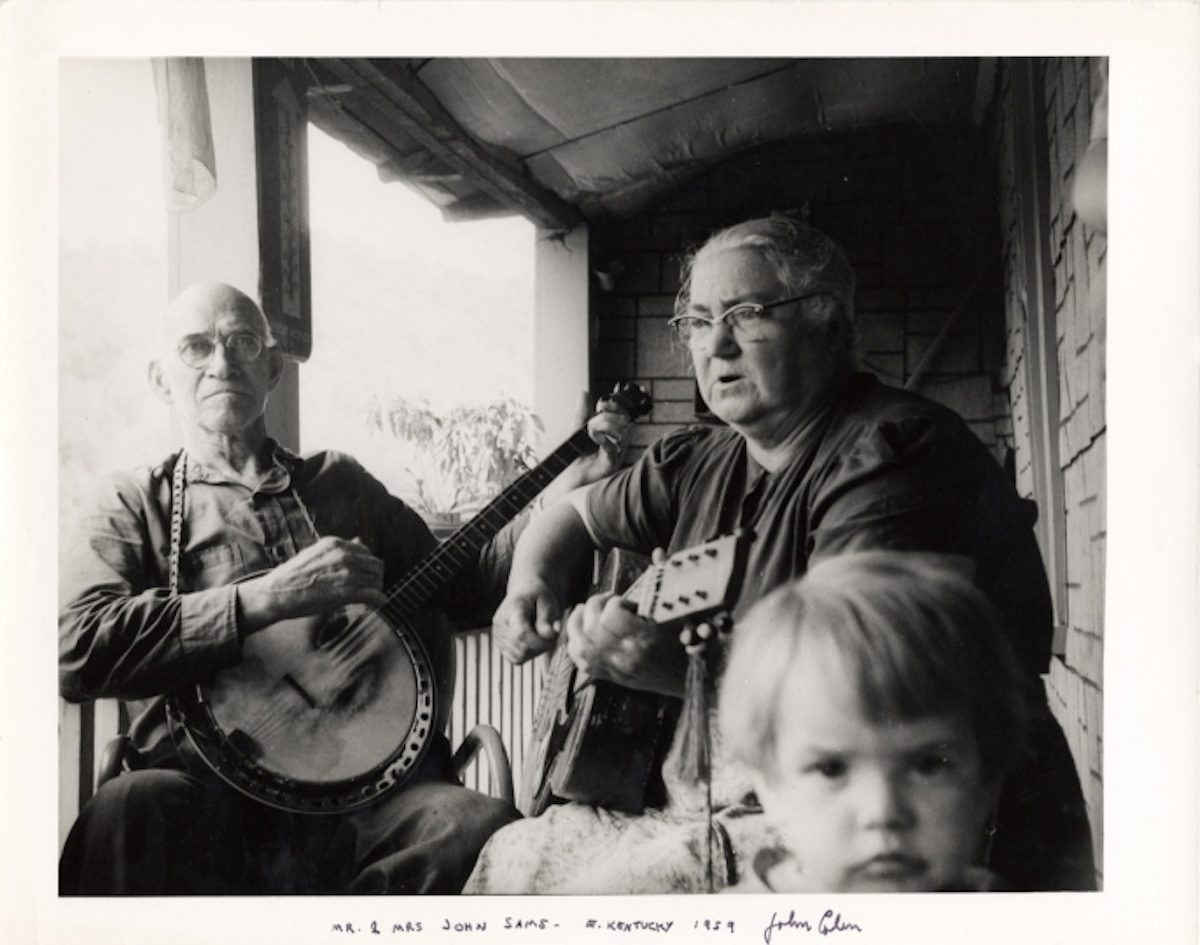

As Cohen tells it in a 2017 interview two years before his death, “When my band the New Lost City Ramblers started in 1958, we tried to get at that music: The music that wasn’t being heard, we tried to perform it. We were showing that city kids or urban kids or kids from another tradition could really involve themselves in performing this music.” The year after his first folk project formed (see him above between legends Doc Watson and Mississippi John Hurt and below with his band), the “twenty-seven-year-old musician and photographer from Queens, bought a bus ticket to eastern Kentucky,” Amanda Petrusich writes at The New Yorker, and went exploring.

He was “looking for ‘Depression songs’…. ‘I said to myself, I’m going to go to Kentucky, because they have a depression going on there. I’ve never experienced a depression—all I’ve heard are the records.’” He did not consider himself a tourist, although he grew up in the New York suburbs, a place as unlike the Kentucky coal towns he visited as any other. His was “a spiritual journey more than a literal one.” Like so many in his generation, Cohen says, “music was an important part of my realization of what a cocoon the suburbs were.” He saw how profoundly he had been insulated from other American lives.

Up to that point, Cohen had spent his career around other relatively privileged, often famous, artists. He was, writes photographer Grant Scott, “the real deal. He hung out and documented the Abstract Expressionists in New York’s Cedar Bar,” and later released a book, Cheap Rents… and de Kooning about his time in the downtown art scene of the late 50s and early 60s. He “photographed the Beats during the filming of Robert Frank’s Pull My Daisy” and sold a famous photo of Jack Kerouac to Life magazine. Cohen “told stories and documented characters from the inside as a photographer and musician steeped in the history of American folk music.”

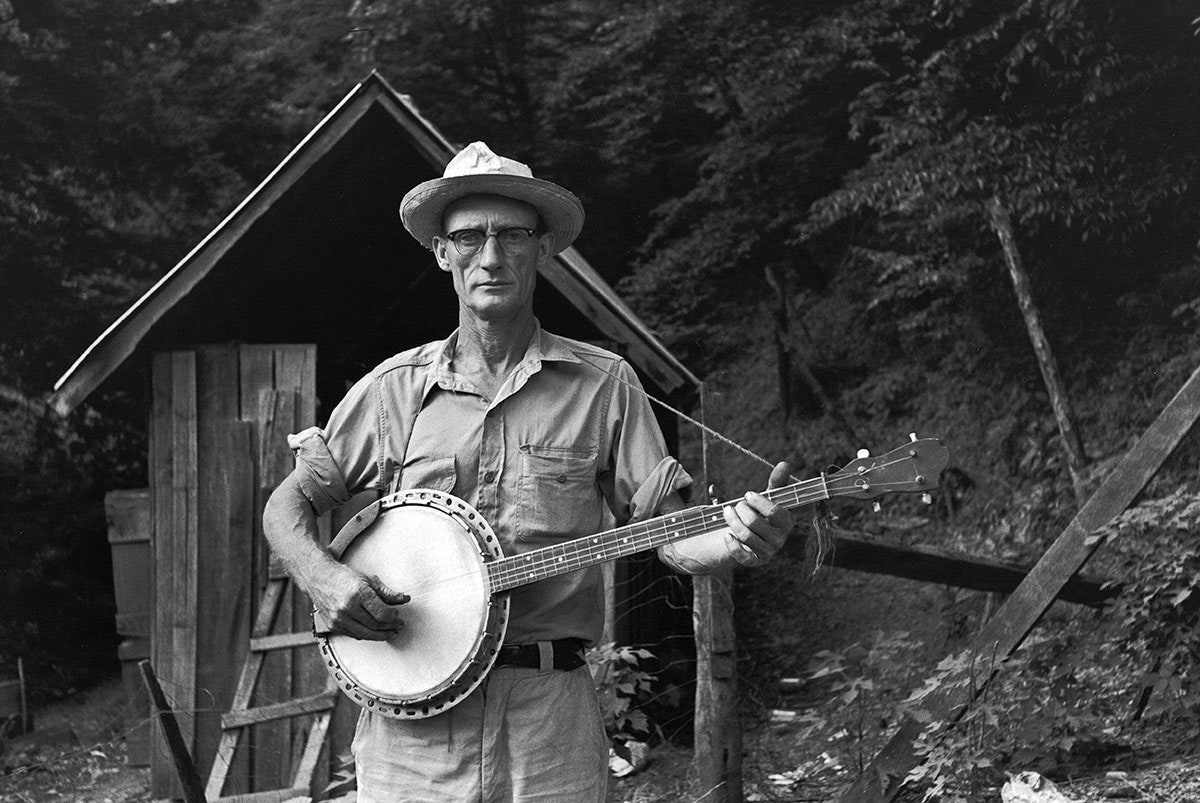

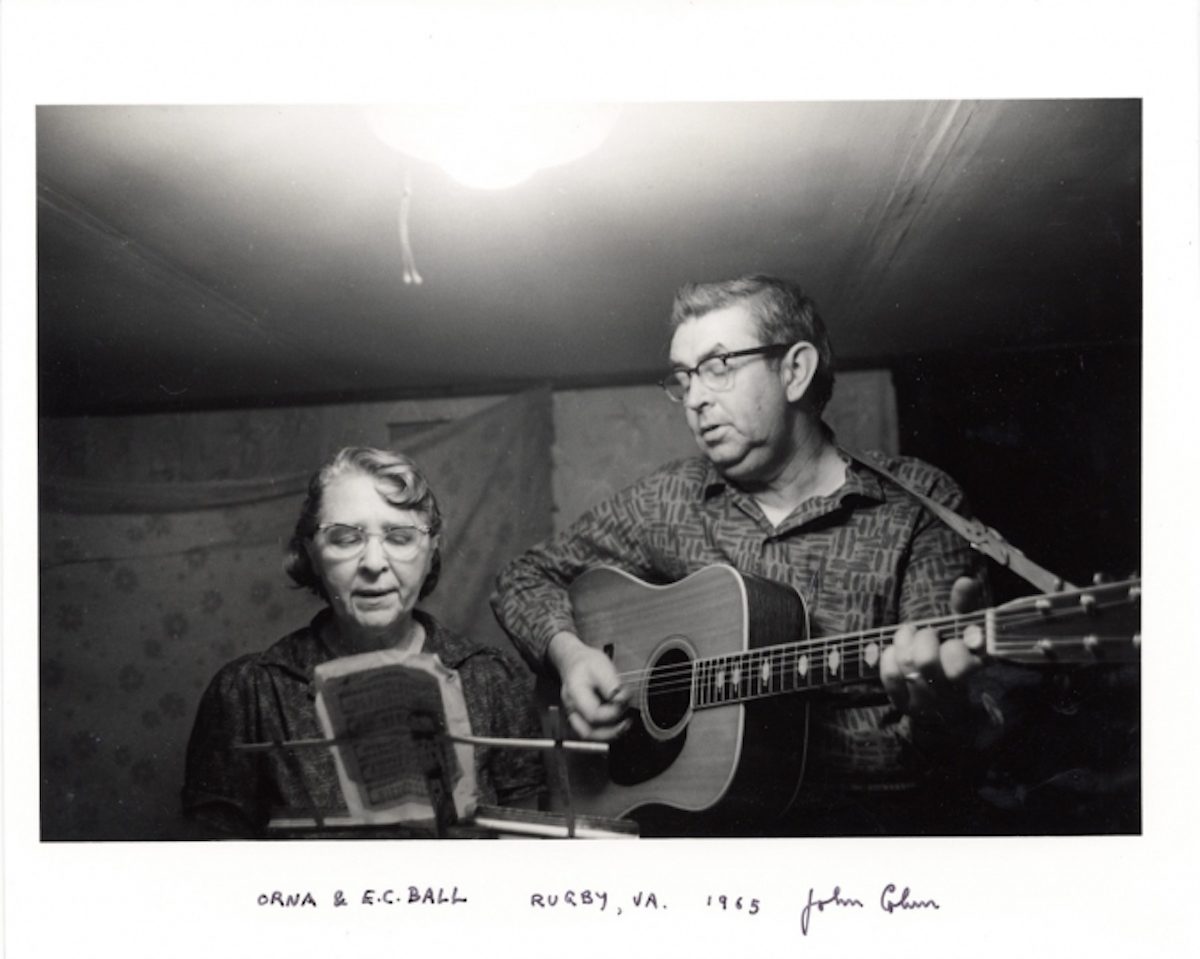

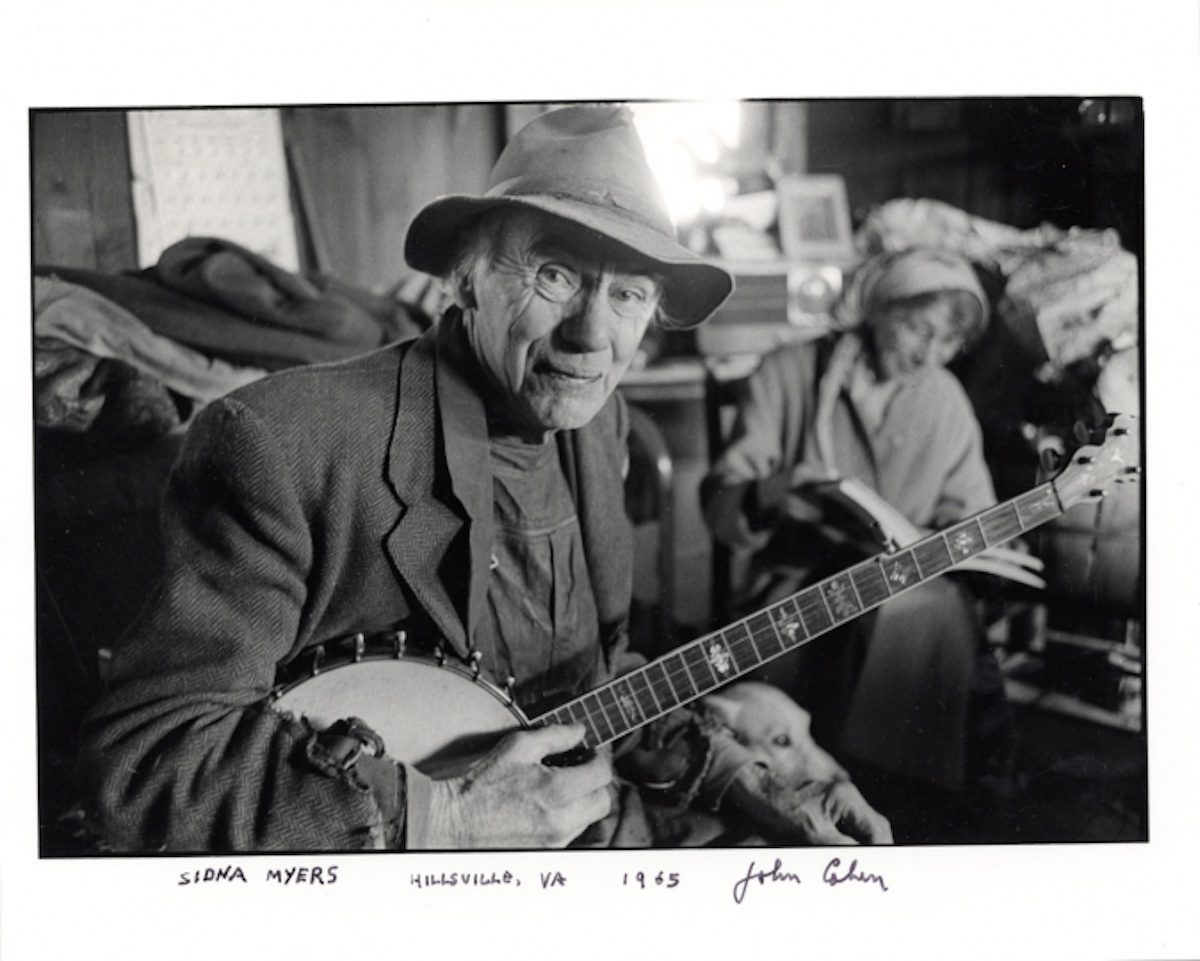

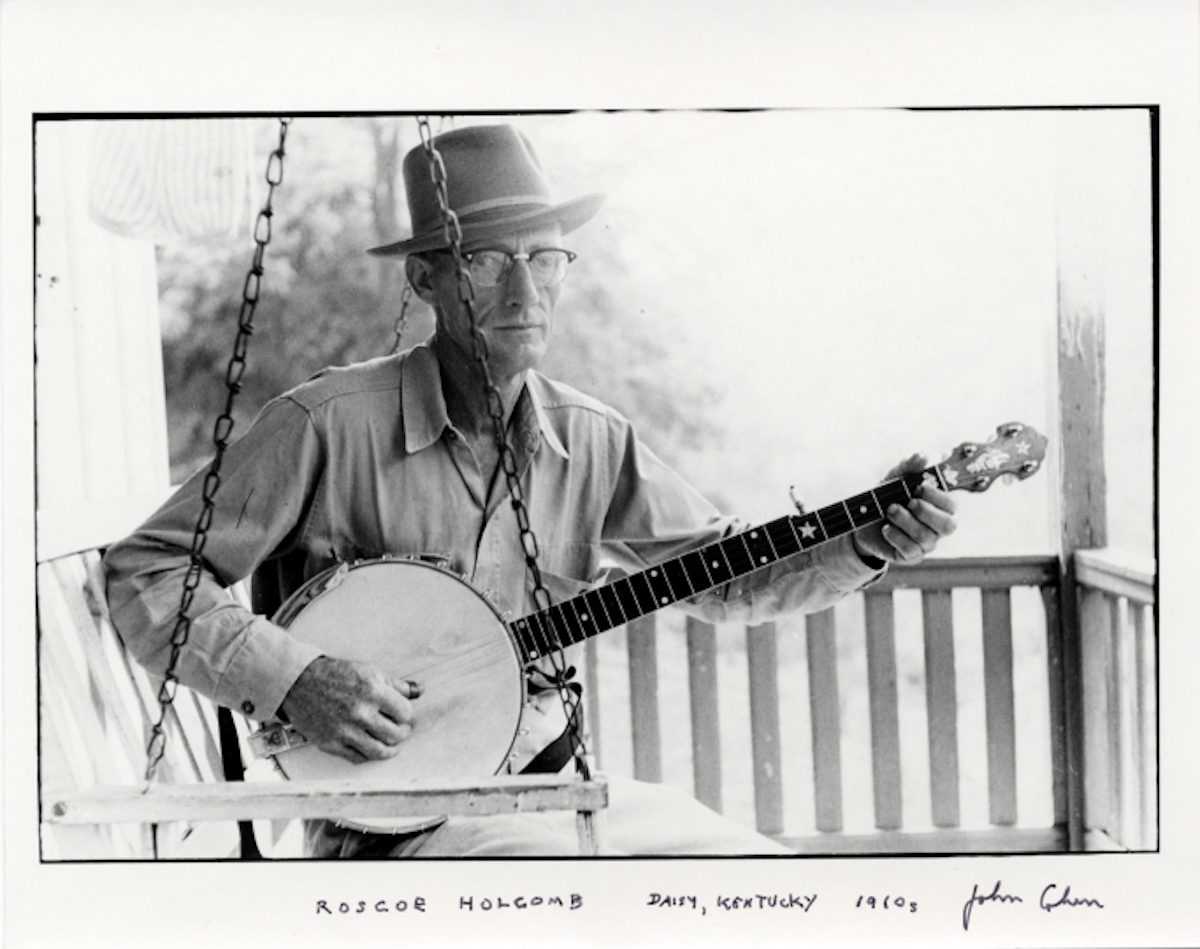

To the people he met in his travels through Appalachia—first Kentucky, then later Virginia and North Carolina—he would remain an outsider. Still, they opened up their homes, tuned up their instruments, sang him the songs they could remember, and let him take their picture in their homes, churches, and home-churches. His quest for “Depression songs” and authentic banjo music lead him to Roscoe Holcomb, a Kentucky coal miner and sawmill worker retired early at 47 from the backbreaking work.

The two formed “an often strange and stilted friendship,” writes Sean O’Hagan, which culminated in Cohen bringing Holcomb to New York to play the folk circuit, recording him, making two short documentaries, and releasing a book of photographs, The High and Lonesome Sound, also the phrase Cohen used to describe Holcomb’s voice, a sound, he said, that “made the hairs on my neck stand on end.” Holcomb was exactly what Cohen had been looking for. “For years,” he says, “I’d heard singers… talking about some old guy out on his back porch singing this wonderful music. And I kept thinking, I want to hear that old guy. Who is that old guy?”

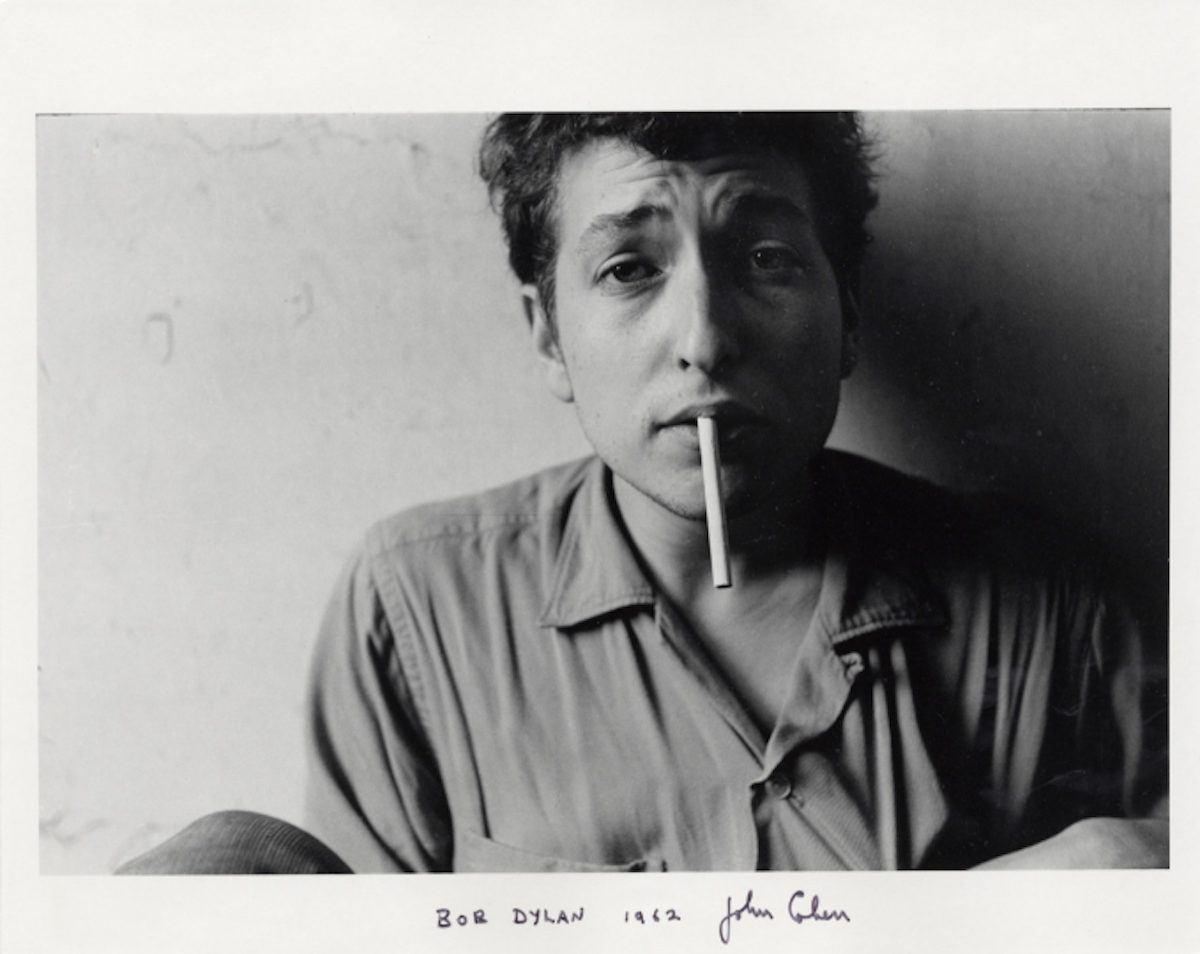

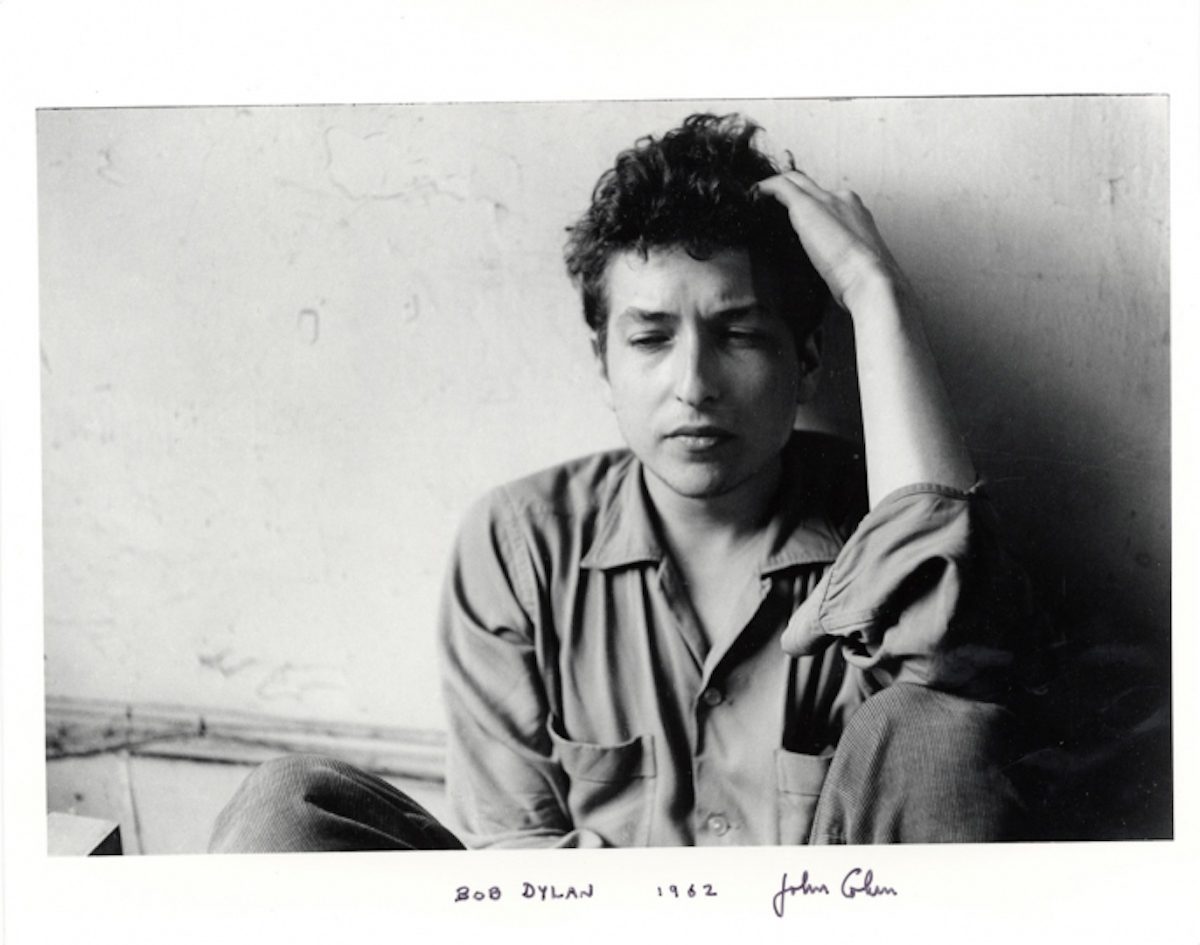

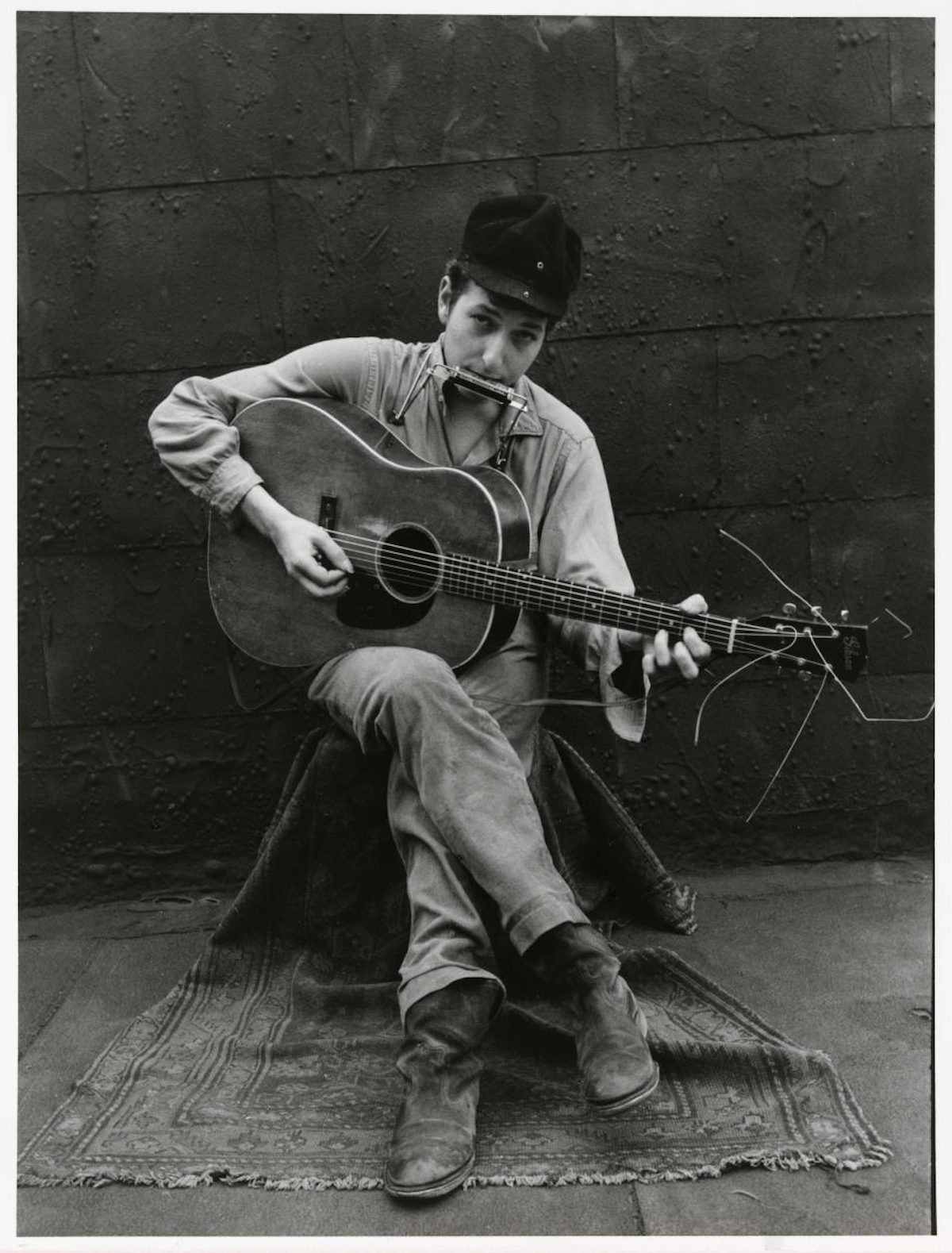

At the same time that he was photographing rural people who carried on the tradition he played in, Cohen was capturing other New York folkies on film, including a young Bob Dylan in his hobo phase. But it was the discovery of Holcomb he seemed most proud of. “If I hadn’t ‘found’ him in Daisy, Kentucky in 1959,” Cohen wrote in an album of Holcomb’s songs, “there would be no record of his music. He never had the desire to record, to on radio, or perform in public…. He was little appreciated or recognized back home in Kentucky.”

Cohen’s “documentary style” of photography, as he called it, after Walker Evans, and his discovery and preservation of traditional songs have netted him comparisons with ethnomusicologists like the Lomaxes, but he resisted the idea of himself as a “preservationist,” saying the word “reminds me of formaldehyde.” Folk music is a living tradition, he maintained, though its sources were dying out even when he met Holcomb, who himself died alone in a nursing home in 1981. Cohen became a Professor of Visual Arts at State University, New York, and taught for over twenty years, continuing to take photographs and play the music that first moved him to go looking for a depression.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.