Visiting England, apparently on a whim and a year before she appeared in her first film The Street of Forgotten Men, a young Louise Brooks became a dancer at the recently opened Café de Paris in Coventry Street. It was late 1924 and during a particularly cold and dismal winter, she became the first person to dance the Charleston in London. Brooks later wrote about her time in the capital: ‘I was living beyond my means – who doesn’t at seventeen? – in a flat at 49A Pall Mall.’

The young American woman had found herself living in a part of London described a few years later as ‘a masculine paradise’ by the travel writer Paul Cohn-Portheim. St James’s, in many respects, hasn’t changed much since.

Louise Brooks in The Street of Forgotten Men (1924)

It was King Charles II who gave Henry Jermyn permission to develop the area of land south of Piccadilly and it was named after the 12th century leper hospital dedicated to Saint James the Less (the hospital site is where St James’s Palace now stands). Jermyn started building St James’s Square around 1664 soon followed by a grid of paved streets one of which he named after himself. This is where the rich and fashionable London man has now shopped for over three hundred years.

Around the time Louise Brooks was dancing the Charleston at the Cafe de Paris the press baron Lord Beaverbrook bought Stornoway House at 13 Cleveland Row. The fourteen-bedroom mansion overlooked Green Park and was described in the estate agent’s advertisement as ‘almost within the precincts of the Palace’.

Lord Beaverbrook

Duke Ellington

It was here, in 1933, that Beaverbrook entertained the jazz bandleader Duke Ellington at a post-concert party attended by the Prince of Wales. It was Ellington’s first visit to London and he was surprised that the Prince’s tipple of choice was gin. After the bathtub versions he had been drinking during prohibition it was a drink Ellington thought of as decidedly ‘low’. The Prince of Wales was an amateur drummer and spent most of the evening closely watching Ellington’s drummer Sonny Greer. At one point the Prince took over the drum-kit and played, apparently, ‘an impressive Charleston beat’. Ellington would later recount that he and Sonny called the Prince ‘The Wale’ all night and that gin was now ‘grand’.

Three years later in October 1936 an effusive Lord Beaverbrook wrote to congratulate a new St James’s neighbour: “Never, never, never was any appointment to an Ambassadorial post in London as well received as your own…You may save the peace of Europe, I truly believe, by your conduct here.” As it happened, and as we all know, the conduct of Joachim von Ribbentrop, the new German Ambassador, did little to save the future peace of Europe. The German Embassy was based at no. 9 Carlton House Terrace which overlooks St James’s Park and was designed by John Nash in the 1820s. Leopold von Hoesch, von Ribbentrop’s predecessor had found it increasingly difficult to hide his feelings about the Nazi regime and in March 1936 told Hitler the invasion of the Rhineland by Germany was a mistake. A month later he was dead from a heart attack in his bathroom and the rumour that he had been assassinated via poisoned toothpaste by the Gestapo never went away.

Von Hoesch’s coffin

Von Hoesch’s body was afforded full honours in England but sent back for a burial in Germany ignored by Nazi dignitaries. The remains of his dog ‘Giro’, however, who had died two years previously after chewing through a electric cable in the garden, stayed in London. His little headstone, moved after building work in the 1960s, can still be seen by the side of a large tree there inscribed: “Giro; ein treuer Begleiter!” [“Giro; a faithful companion!”]

Von Ribbentrop’s dislike of the English and their odd sense of humour, was only intensified when he was forced to play musical chairs after dinner at Nancy Astor’s London home at 4 St James’s Square. The host whispered to the English amongst the distinguished guests that they were under orders to let the Germans win.

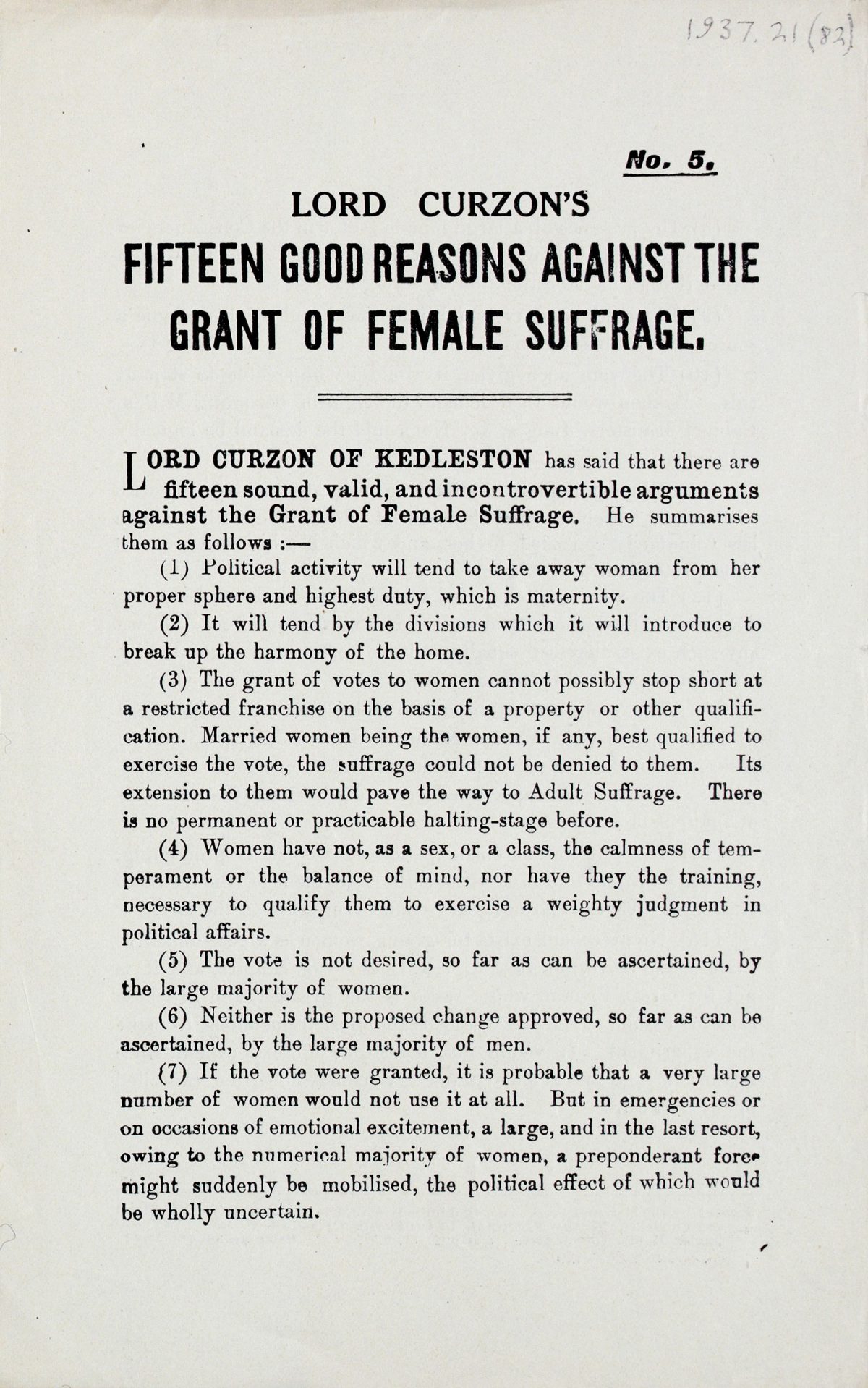

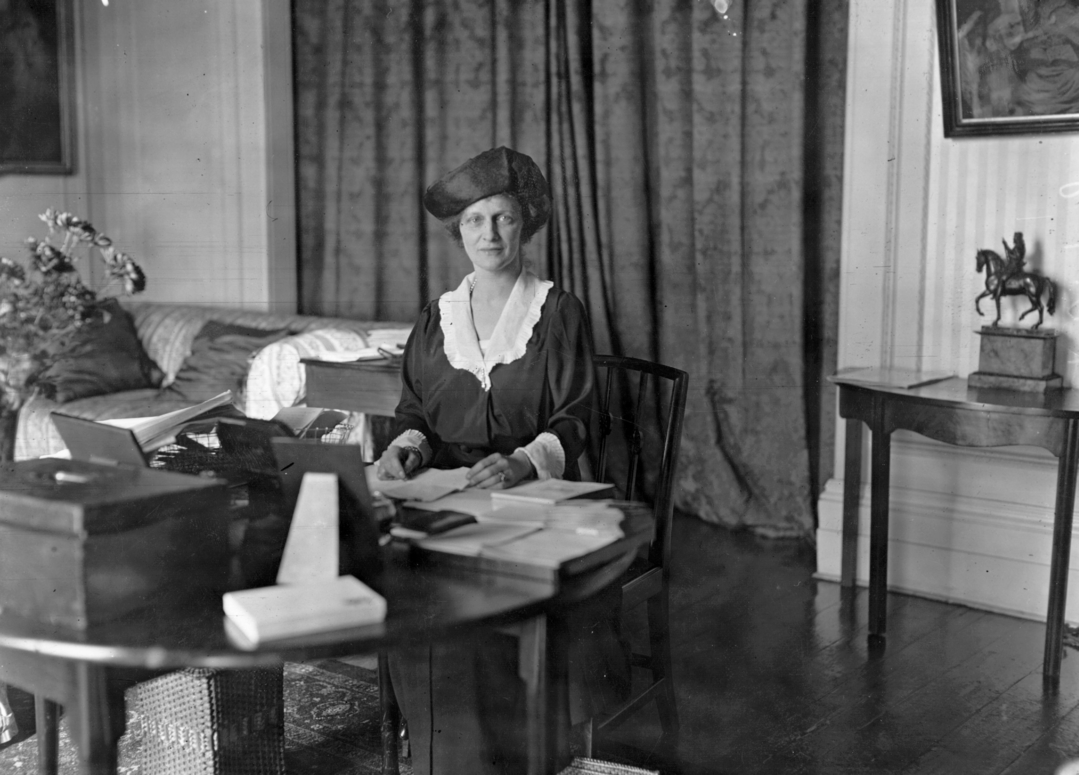

No. 1 Carlton House Terrace, along from the German embassy, was once the residence of Lord Curzon who served as the Viceroy of India from 1899 to 1905 and became the President of the National League for Opposing Woman Suffrage in 1912. He soon published a pamphlet entitled ‘Fifteen Good Reasons Against the Grant of Female Suffrage – the fourth of which stated, “Women have not, as a sex, or a class, the calmness of temperament or the balance of mind, nor have they the training necessary to qualify them to exercise a weighty judgement in political affairs.” About seven years later, in December 1919, Nancy Astor became the first woman to take at seat in the House of Commons when she became MP for Plymouth Sutton.

On the west side of Carlton House Terrace is a cul-de-sac called Carlton Gardens also built by John Nash from 1830 to 1833. After WW2, MI6’s particularly secret Section Y was based at number 3. It’s job was to intercept Soviet military and diplomatic communications and was so secret that most of the SIS knew not of its existence. Unfortunately one person who did know was the Soviet spy George Blake who worked there after the war. After confessing to espionage activities in 1961 he was, ironically, bought back to Carlton House Terrace to be interrogated. It is said that he betrayed details of some forty MI6 agents to the KGB and Blake would later write, “I don’t know what I handed over because it was so much”. He was sentenced to 42 years imprisonment in May 1961 but five years later, in October 1966, Blake escaped from Wormwood Scrubs prison with the assistance of three men whom he had met in jail. As of June 2020 he is still alive and living in Moscow on a KGB pension insisting that he had never felt British: “To betray, you first have to belong. I never belonged”.

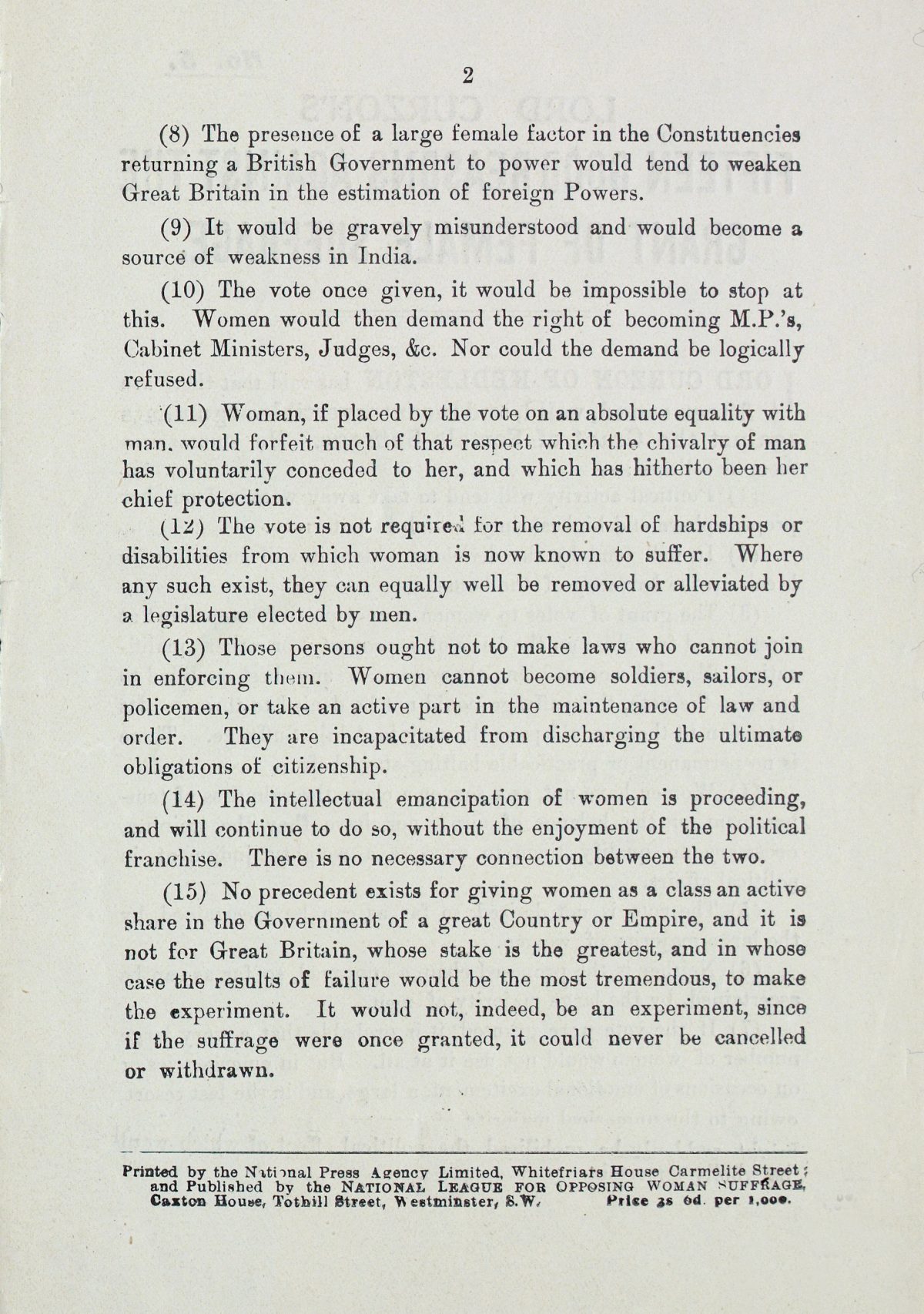

About 400m north-west of Carlton House Terrace and exactly a month before George Blake absconded to the Soviet Union, Jimi Hendrix jammed on stage at the Scotch of St James nightclub in Mason’s Yard. It was his first performance in the UK and he had flown to London earlier that day bringing with him nothing but a Fender Stratocaster, a change of clothes and some acne cream.

The very trendy ‘Scotch’ had a tartan decor in an attempt to look like a Scottish hunting lodge. Its look and location symbolised how the new artistic in-crowd were encroaching on the old establishment but not everyone liked it, ”It’s like a rhythm-and-blues Angus Steak House,’ once moaned David Hockney.

Model outside the Scotch of St James

In the same courtyard at number 6 was the Indica Gallery and Book Shop which opened in the summer of 1965. John Lennon visited on 1 April 1966 and bought The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based On The Tibetan Book Of The Dead by Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, and Ralph Metzner. At the beginning of the book’s introduction it says: “When in doubt, relax, turn off your mind, float downstream.” Lennon later wrote about taking LSD for the first time. “I did it just like he said in the book, and then I wrote Tomorrow Never Knows, which was almost the first acid song: ‘Lay down all thoughts surrender to the void,’ and all that shit which Leary had pinched from The Book Of The Dead.” The Beatles began recording Tomorrow Never Knows on 6 April 1966, just five days after Lennon’s visit to Indica.

Timothy Leary book

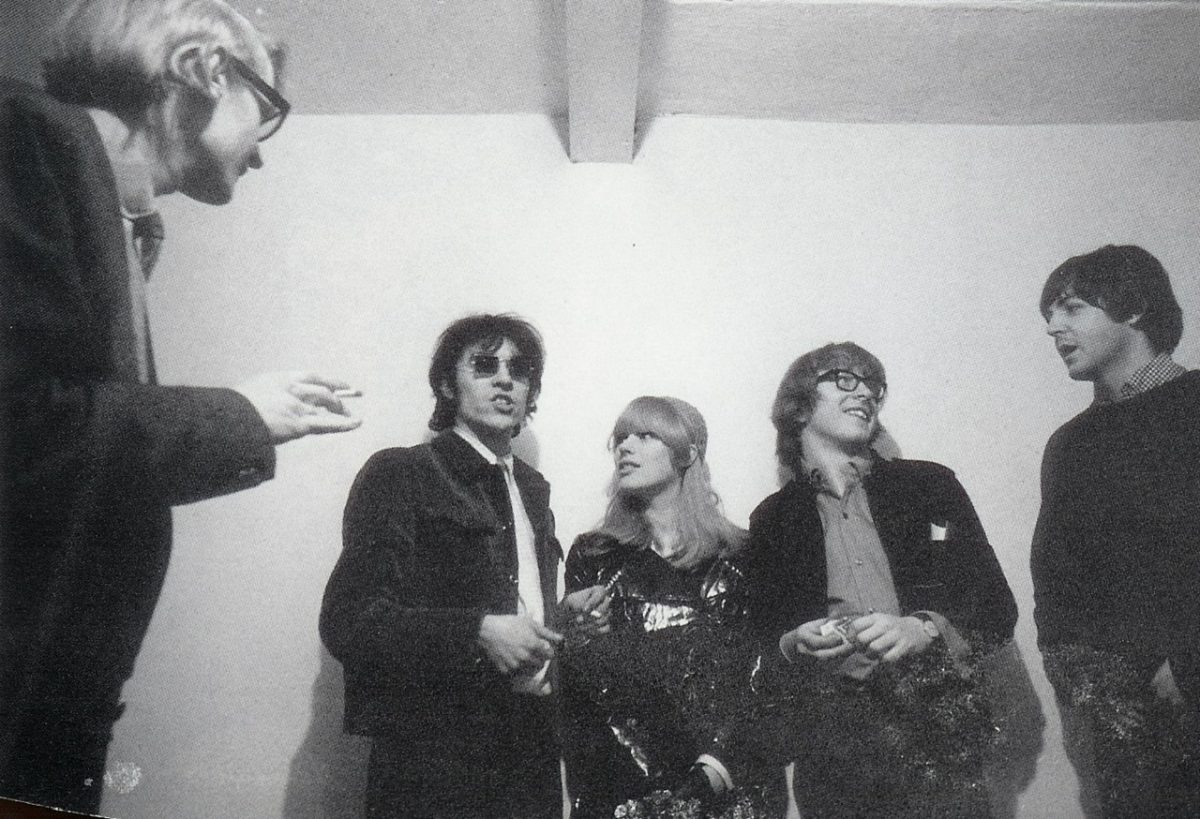

Barry Miles, John Dunbar, Marianne Faithfull, Peter Asher, Paul McCartney at the Indica Gallery opening in London | 1965 | Photographed by Graham Keene

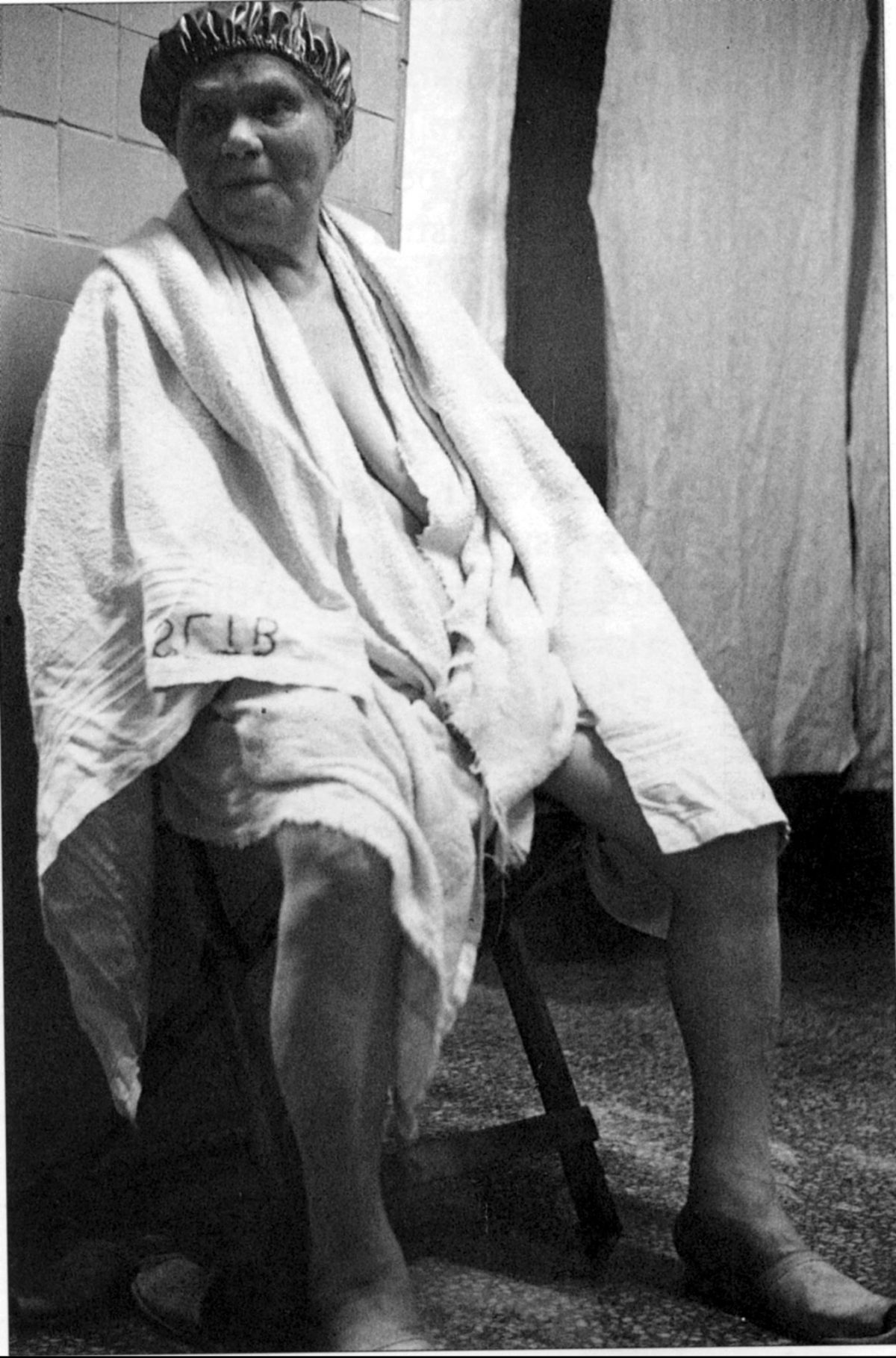

Late in 1951, a young woman called Grace Robertson, one of the few female professional photographers of the time, spent a day amongst the regular clientele in the tarnished and faded elegance of the Savoy Turkish Baths at 12 Duke of York Street. Robertson photographed the women for Picture Post magazine as they went from one hot room to the next which was then followed by a cleansing pummel in the bath’s marble wash-house. It was directly around the corner from the all-male Savoy Turkish Baths at 32 Jermyn Street which was where Christopher Isherwood and WH Auden took the 24 year old Benjamin Britten in 1937 around the time of their collaboration for the GPO film Night Mail produced by Basil Wright. “Well,” Basil asked Isherwood afterwards, “have we convinced Ben he’s queer, or haven’t we?” Britten wrote in his diary of his experience at the baths: “Very pleasant sensation. Completely sensuous, but very healthy. It is extraordinary to find one’s resistance to anything gradually weakening.”

The women-only Savoy Turkish Baths on Duke of York Street in St James, 1951. Photo by Grace Robertson

The women-only Savoy Turkish Baths on Duke of York Street in St James, 1951. Photo by Grace Robertson

The Savoy baths weren’t the first Turkish baths to be built in Jermyn Street. In 1862 the London and Provincial Turkish Bath Co. Ltd. built what was said by some to be the finest in Europe at number 76. Although it was both grand and spectacular it closed down at the beginning of WW2 and a few months later was completely destroyed after a parachute bomb exploded above Jermyn Street on 17th April 1941. The same bomb killed the popular singer Al Bowlly while he was reading a cowboy book in bed in the adjacent Duke’s Court apartments.

It may have been changing fashions or the police raids had become too frequent but the last of the Jermyn Street baths closed in 1975. The women’s baths in Duke of York Street, perhaps always a bit of a mismatch in the ‘masculine paradise’ of Jermyn Street and its environs, had closed much earlier in 1958.

1st November 1919: American-born British politician Nancy Witcher Langhorne, Viscountess Astor (1879 – 1964), Conservative candidate at the Plymouth election sitting at a worktable. She won the election and became the first woman member of parliament. (Photo by G. Adams/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

Nancy Astor’s house at 4 St James’s Square, actually the oldest house in the square, was sold in 1946. It marked both the end of Nancy’s political career but also the political influence of the gatherings and soirées at the large London houses. Margaret Thatcher unveiled an English Heritage plaque for Astor on the building in 1987 and praised her courage for going into ‘that totally male-dominated place’.

She meant the House of Commons of course but she almost could have been speaking about the male dominance of St James’s. There is, however, one more woman perhaps more than any other who will always be associated with the area. On the 17th April 1984, three years before the unveiling of Nancy Astor’s plaque next door, there were around 75 people protesting outside the Libyan Embassy – or the Libyan Peoples’ Bureau as Colonel Gadaffi preferred it to be called. At 10.18 a.m., a submachine gun poked out of the embassy’s first-floor window and fired into the crowd of protesters. One victim was a 25-year-old police officer – WPC Yvonne Fletcher.

On 1 February 1985 her memorial – a granite and Portland stone commemorative pillar that lies in the north-east corner of St James’s Square – was unveiled by Margaret Thatcher. It faces the former Libyan Embassy.

Police officers surround police constable Yvonne Fletcher after she was shot outside the Libyan embassy in London. Photo – Reuters

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.