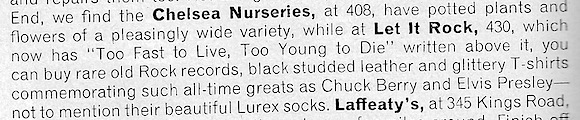

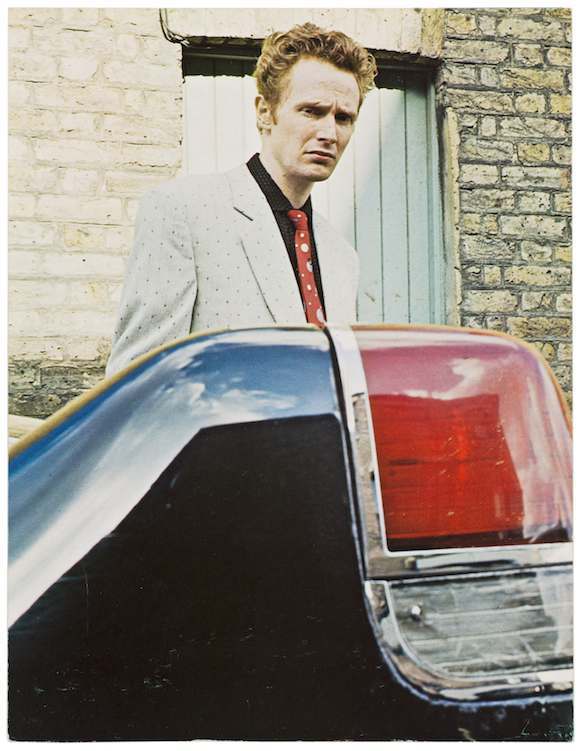

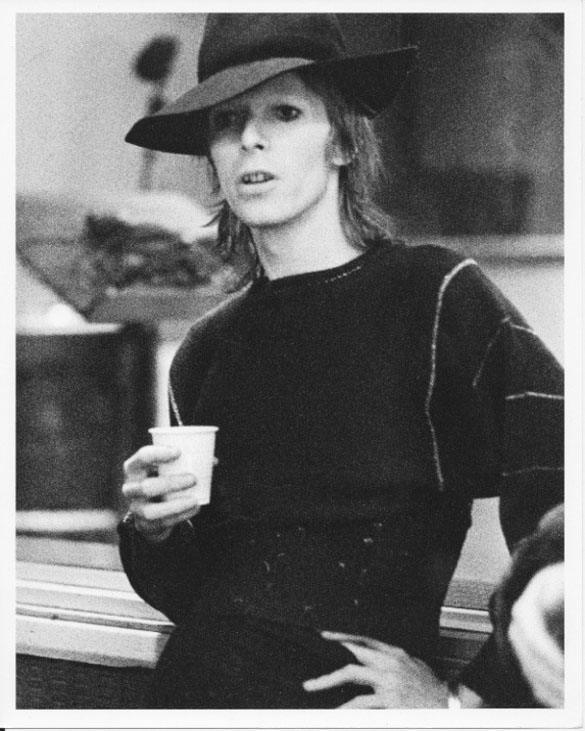

David Bowie recording the Diamond Dogs LP at Olympic Studios, Barnes, south-west London, January 1974 during his residency in Chelsea’s Oakley Street.

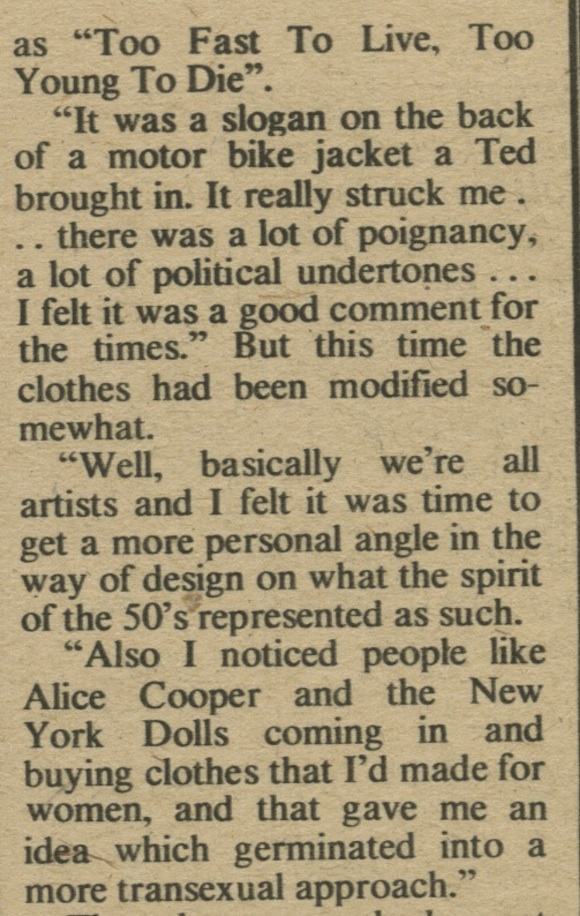

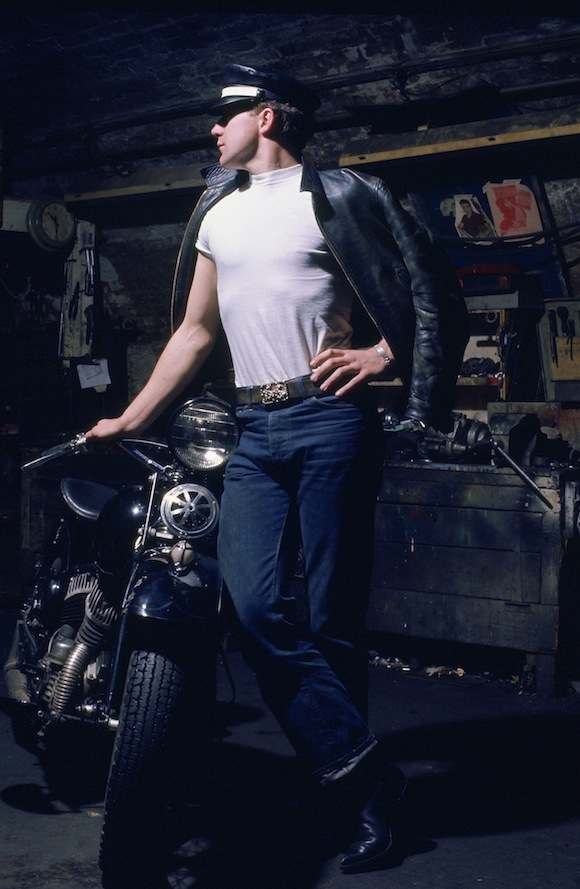

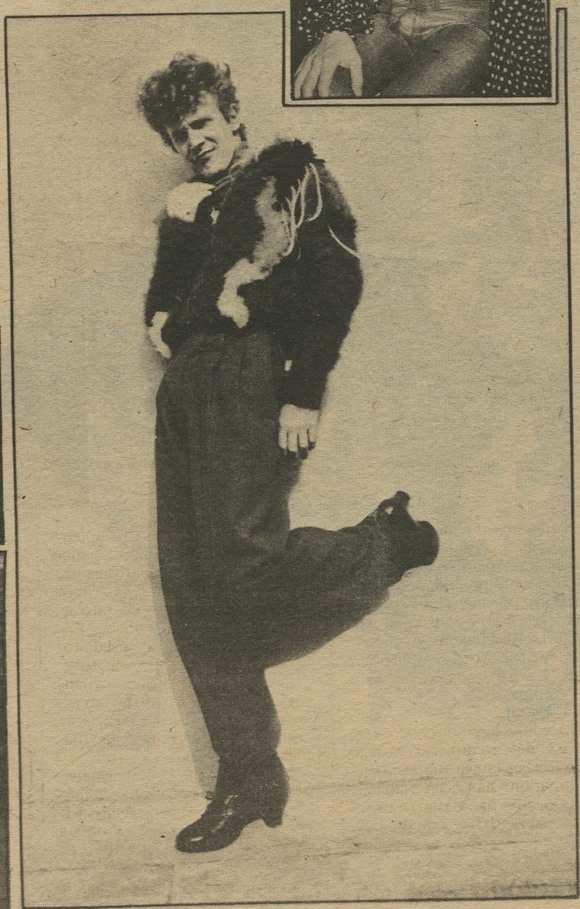

Malcolm McLaren in Too Fast To Live Too Young To Die designs, Chelsea, London, from New Musical Express, April 6, 1974

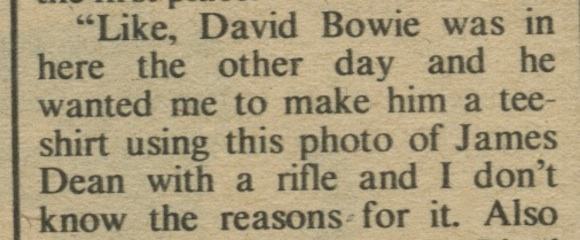

It is a little known fact that David Bowie was an occasional visitor to 430 King’s Road when it was operating as Too Fast To Live Too Young To Die.

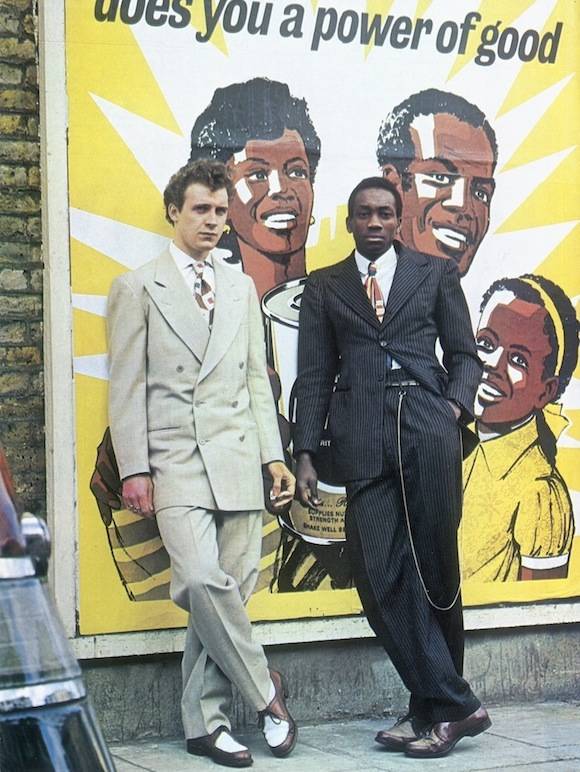

This manifestation of Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s revolutionary boutique – which paid design tribute to the fetishistic studded leather attire of Britain’s early 60s Ton Up Boys and rockers and sold the cult clothing associated with 40s mobsters and Latino zoot suit rioters – succeeded the 50s outlet Let It Rock in the early spring of 1973, as noted at the time by the fashion writer Catherine Tennant in British Vogue.

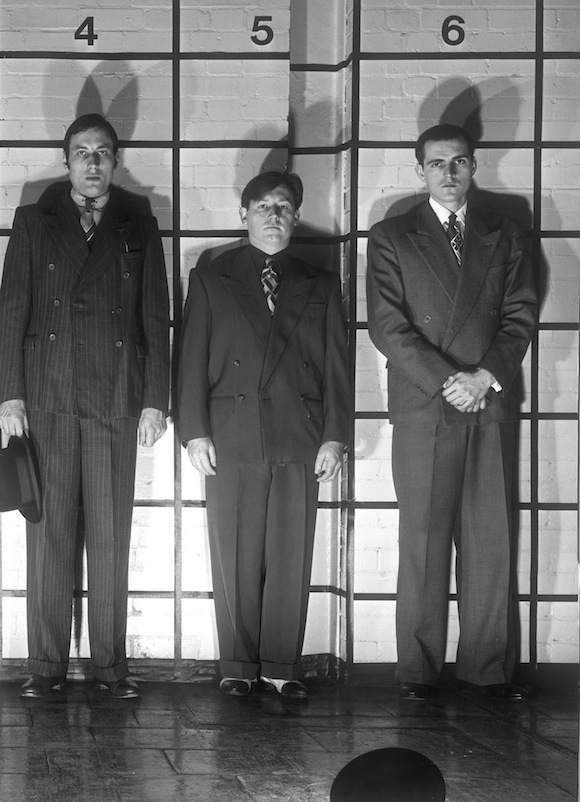

Malcom McLaren’s coffin is carried into church at his funeral in North London on April 22, 2010 in London, England.

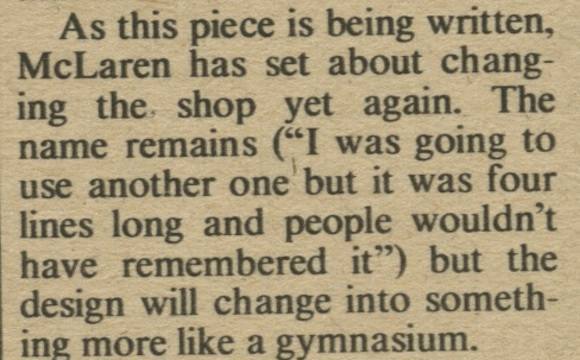

TFTL lasted about a year; by April 1974 McLaren was preparing for the next incarnation, Sex, as he indicated to Nick Kent in the pages of the New Musical Express.

TFTL’s relatively fleeting existence coincided with Bowie’s residence in a house in neighbouring Oakley Street, where he lived between October 1973 and April 1974 (when Bowie left England, never again to reside here).

A few years before his death, McLaren told me over lunch about his decision to give up on TFTL; he felt at the time that this phase and Let It Rock had been mere exercises in nostalgia.

“They were revivals, digging in the ruins of past cultures that you cared about,” emphasised McLaren, who, as leaseholder of 430 King’s Road, made the decisions on the successive manifestations without recourse to Westwood. “It was giving those ruins another brief moment in the sun. It wasn’t about doing anything new. It was a series of homages. It was nostalgia. That’s why I stopped it.”

One day, as McLaren toyed with new names and concepts for the shop, a Bohemian character arrived with a large painting depicting the broken body of a rocker who had been thrown from his bike.

The artist told McLaren he had been inspired to paint it by the atmosphere of TFTL, and asked if he could prop the painting against the back wall while he made a visit to a friend in the country. If it sold, then McLaren could take a cut. If not, the individual promised to collect the artwork a few weeks later.

“A few days later, David Bowie wandered in,” McLaren told me in 2008. “He was living nearby and looked utterly alone and miserable. It was a quiet day. I was on my own minding the till. Bowie browsed the leather jackets and studded tops, looked around the shop and ended up at the back, studying the painting.

“After a few minutes he said wistfully and to himself, with his back to me:

“‘You know, a year ago, I would have bought that.’

“And then he wandered out. A few months later he left England for good.”

McLaren told me he caught up with Bowie in LA in the 80s and mentioned the visit. Bowie confirmed that his private life had been in turmoil as he wrestled with the psychic after-shocks of experiencing the Ziggy Stardust phenomenon as he recorded what was to become the Diamond Dogs LP.

“He told me that he felt at the time the only way for him to survive was to escape,” said McLaren, who admitted that back in 1974 he had reflected long and hard on the encounter as he got to grips with the transformation of 430 King’s Road into Sex.

Once this was complete, in the early autumn of that year, McLaren too escaped, to America and the adventures with the New York demi-monde which on his return six months later informed his management of the shop’s customers and assistant Glen Matlock as they became the Sex Pistols.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.