There are those who will tell you the end of the Cold War started when Bob Hope invited Russian President Nikita Khrushchev to come visit Disneyland. Khrushchev came to America but never shook hands with Mickey Mouse in Anaheim, California. Then there are those who suggest it was when President Ronald Reagan told President Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down” the Berlin Wall and set the East German people free.

Though this did eventually happen, I have often considered there was an incident not too long before Reagan’s famous speech that really set the ball rolling. A small moment that signalled the Great Bear of the USSR would never get the better of the USA.

That moment was when bushy-eyed Leonid Brezhnev, the fifth leader of the USSR, ran across the tarmac to bear-hug his favourite actor, and star of his favourite TV show The Rifleman, Chuck Connors, who then lifted the Soviet leader clear off the ground.

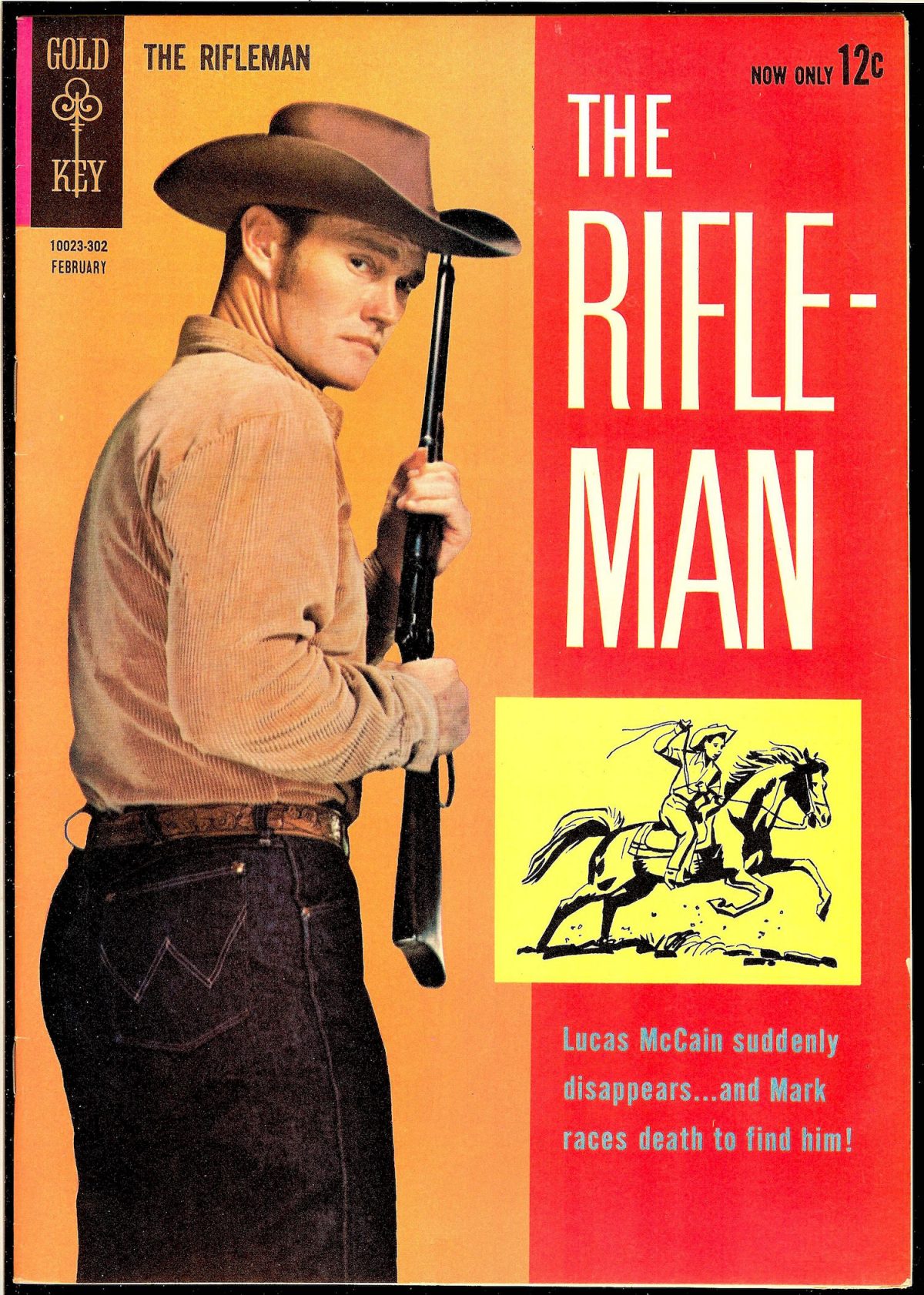

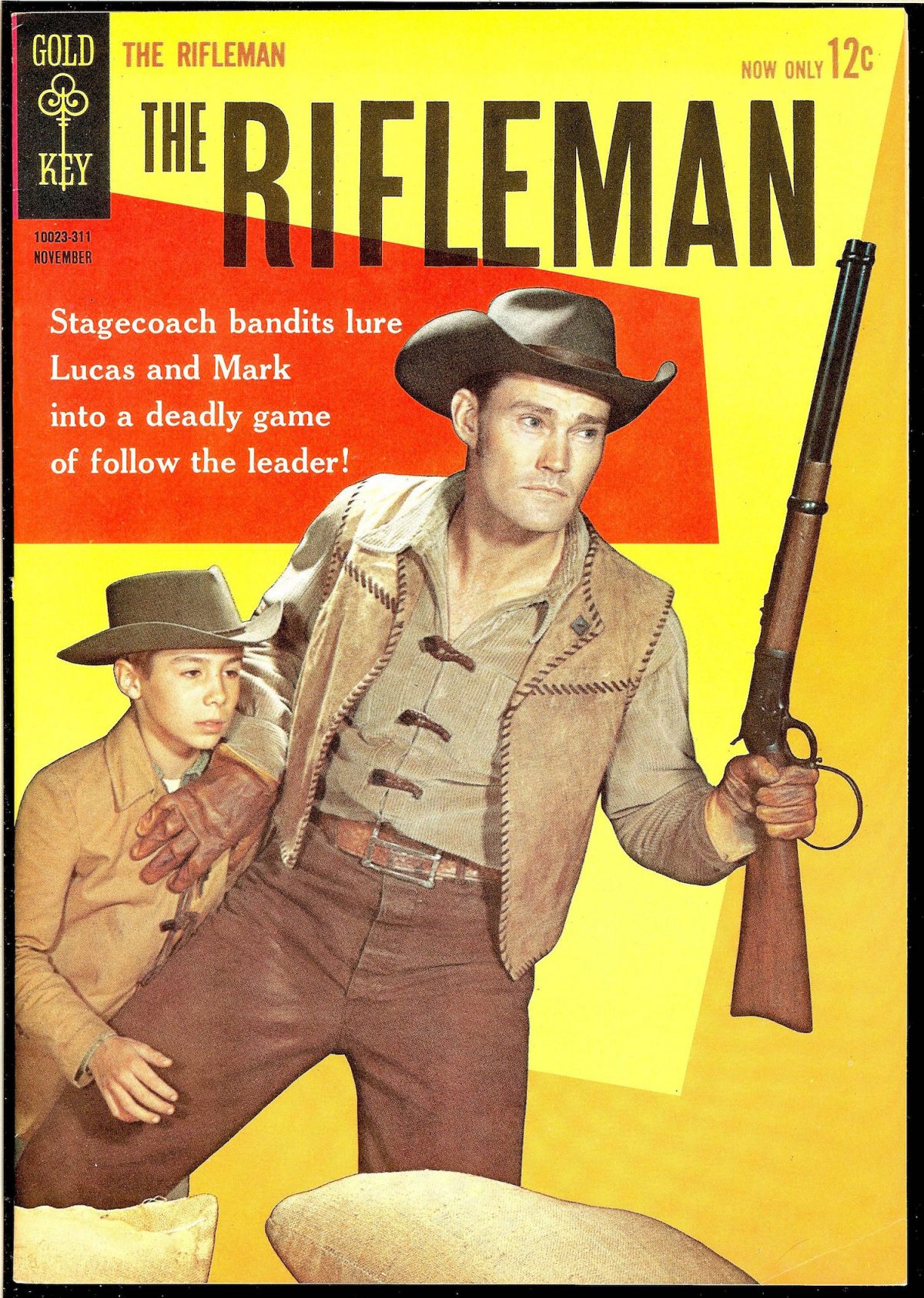

The Rifleman was a hit cowboy television series devised by Arnold Laven and developed by Sam Peckinpah, which aired between September 1958 and April 1963 on ABC.

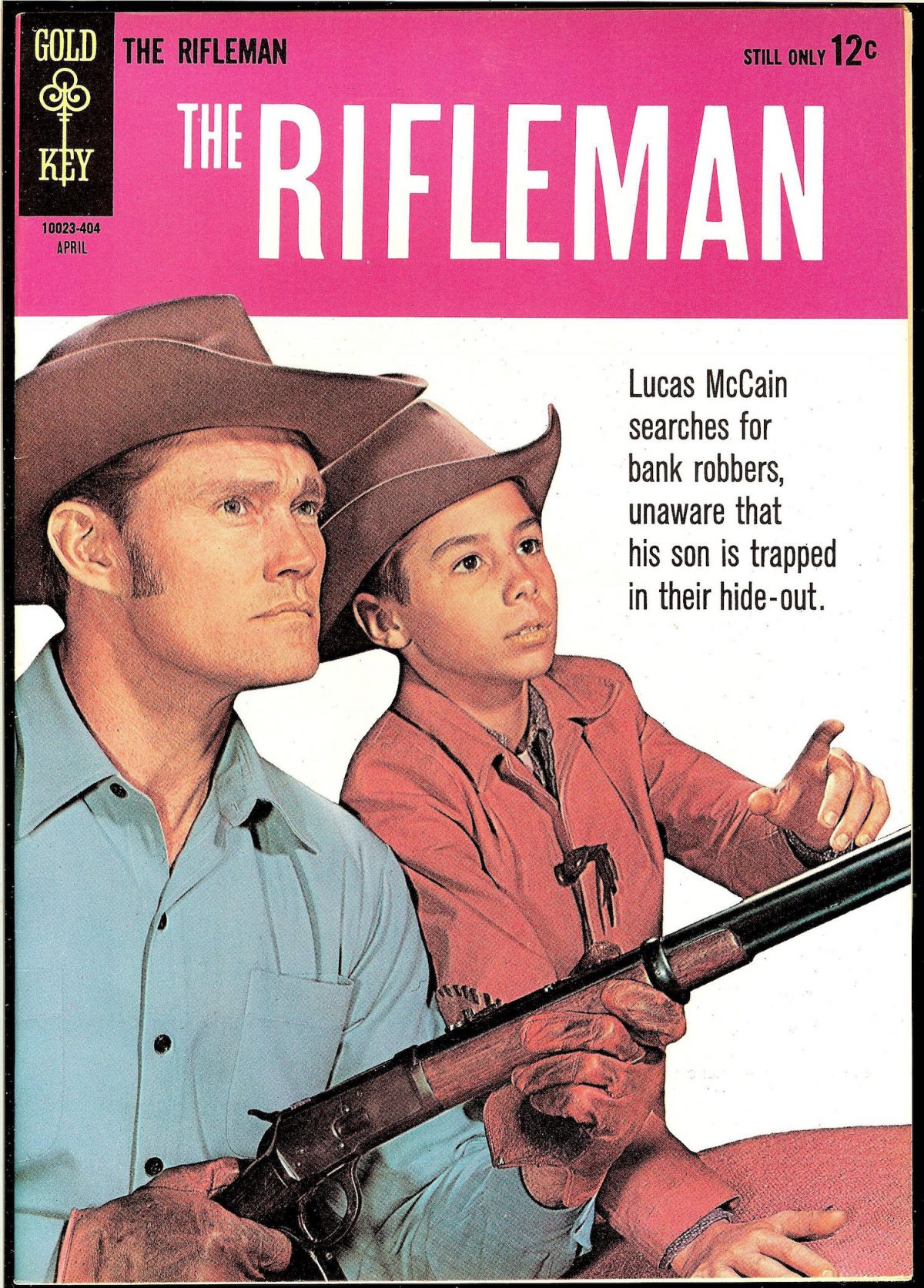

Connors starred as Lucas McCain a widowed father raising his son Mark McCain (Johnny Crawford) in the wild west of the 1880s. Peckinpah wrote storylines around his own childhood experiences of working on his grandfather’s farm, and his memories of hanging around cowboys believing he was home on the range. Peckinpah saw the cowboy as a metaphor of the outsider looking for meaning in a cruel nihilistic world.

Connors later said he thought his role as The Rifleman was “a good image” as the series presented:

[T]he simplicity of the love between the father and the son. That was the foundation. The rifle was for show, but the relationship was for real. There was some violence, but at the end, I would explain to the boy that the violence was not something we wanted to do, but had to do.

Lucas was a righteous character, despite all the violence. We had the benefit of the father-son relationship, so I could have a little scene at the end of the show where I would explain to Mark, essentially, that sometimes violence is necessary, but it isn’t good. And there was a lot of violence on The Rifleman.

We once figured out that I killed on the average of two and a half people per show. That’s a lot of violence, but it was always covered by the scene with the little boy. And he would say, in essence, “Gee, you won Pa”. And I would say, “Wait a minute son. You never win when you kill someone. It demeans you, it takes something away. People have got to learn to do away with violence and guns, and to love each other”. And the viewers would forget the fact that I had killed three people during the show, because of the tender epilogue with Mark. The warm father-son relationship was the heart of the program, and not only did we perform it, but Johnny and I became very close friends.

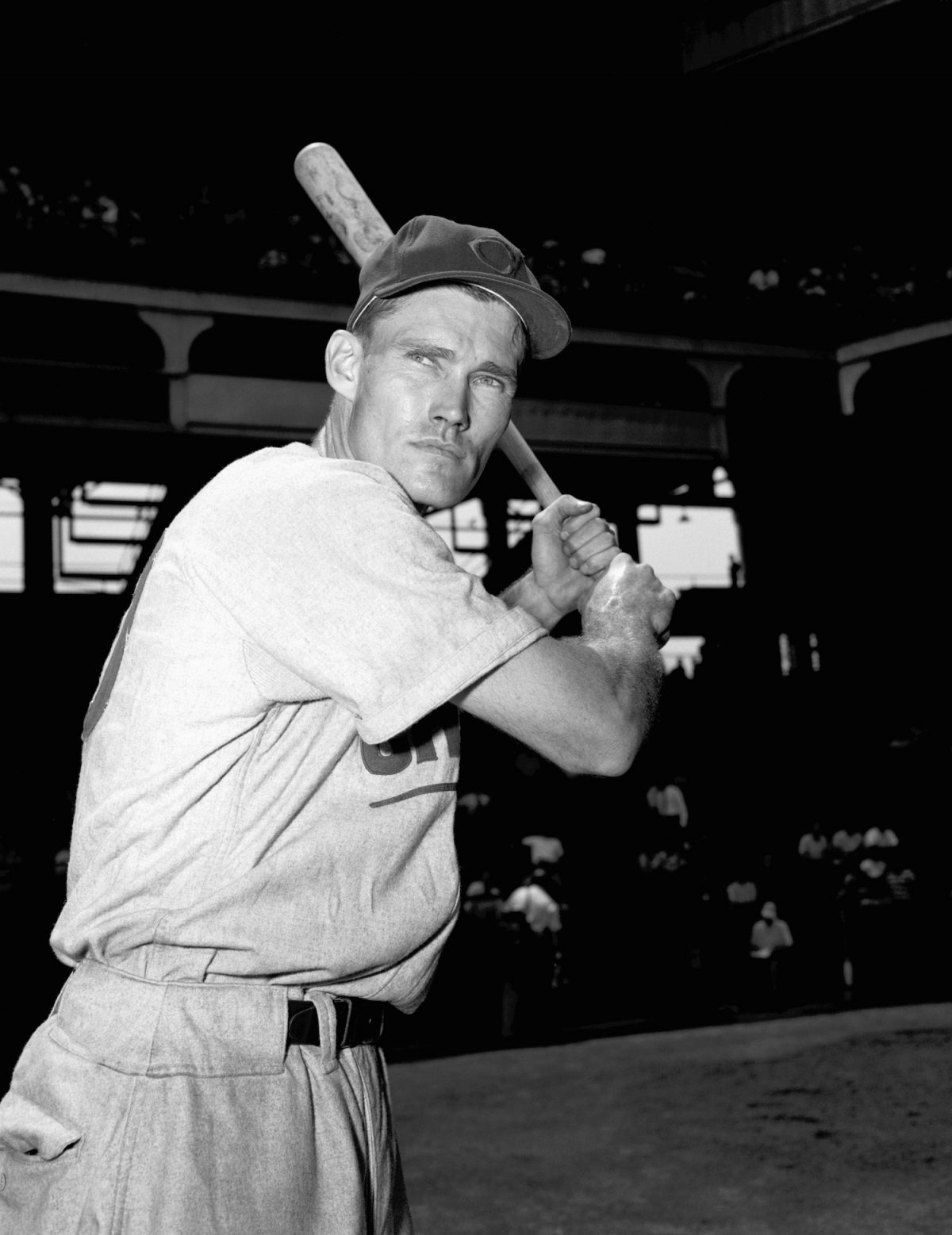

Kevin Joseph Aloysius Connors was the eldest of two children born to an Irish immigrant family in Brooklyn on 10th April 1921. Raised a Catholic, Connors was an altar boy at the local church, the Basilica of Our Lady of Perpetual Help. As a child, he displayed considerable athletic prowess which earned him a scholarship to the Adelphi Academy. On graduation, he was offered further scholarships from several colleges but opted to attend Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey, where he began his baseball career

His first name “Chuck” came from Connors constantly yelling at the pitcher, “Chuck it to me, baby, chuck it to me!” He played for the Newport Dodgers 1940-42, until he was enlisted for service in the US Army.

At the end of the Second World War, six-foot-six Connors played basketball for the Boston Celtics. He quit after two years to return to baseball signing-up for the Brooklyn Dodgers junior league before joining the Chicago Cubs in 1951. He played 66 games as first baseman and pitch-hitter.

In 1952, Connors was farmed out to the Los Angeles Angels. Thinking he was never going to make it in the major league, Connors considered a career in Hollywood. He got lucky. He was spotted by a talent scout, who cast him as a cop in the Spencer Tracy/Katherine Hepburn movie Pat and Mike. With his blonde-hair, good looks and muscular-build, Connors was soon in demand as a cop, cowboy, or soldier.

In 1958, he beat 40-other actors for the lead role as Lucas McCain in the series The Rifleman.

Leonid Brezhnev liked hunting. He liked to track through the woods at the Zavidovo Preserve to hunt for deer and boar and any other goddam critter that got in his way. On one trip, Brezhnev was nearly killed after he fired two rounds into a gnarly wild boar. The beast went down. Brezhnev walked towards his kill thinking of sausages and beer. The boar stirred. It got up quickly, turned and hurtled towards the Soviet President. Both barrels of his MTs-10 were empty. Damn. The dark-tufted beast lowered its tusks intent on gutting Brezhnev. A dozen paces between them. No place to hide. When two shots fired from behind Brezhnev’s right shoulder. One of his guards had seen the danger. The first bullet missed. The second caught the boar on the flank sending it back and away from Brezhnev. It ran squealing towards the dark of the woods.

Between 1962 -87, soviet citizens were not allowed to own rifles or handguns in Communist Russia. Only those who had a license through work (hunters, trappers, herders) could have use of one but they could never own these weapons. Guns were the property of the state and only given out on loan. Of course, this did not apply to Brezhnev, who had his own stock of weapons stored at his luxurious dacha.

Brezhnev also had a passion for fast foreign cars–particularly American automobiles which he liked to drive at full speed around the streets of Moscow with complete disregard for the safety of his fellow citizens.

When given the gift of a Lincoln Continental by President Richard Nixon in 1973, Brezhnev asked if he could drive the car around the streets of Washington D.C. “I will take the flag off the car, put on dark glasses, so they can’t see my eyebrows and drive like any American would,” he said. To which National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger replied: “I have driven with you and I don’t think you drive like an American!”

During his visit to America in 1973, Brezhnev let it be known he was a fan, a BIG fan of the TV series The Rifleman, and an even bigger fan of its star Chuck Connors.

Connor’s noble frontier man appealed to ole Bushy-Brows because he possibly considered himself similar in character to the fictional Lucas McCain. Brezhnev was a man fighting for good in a world without meaning. He was also a man who cared for his family and ensured their comfort and safety–even if it did mean considerable corruption and nepotism on Brezhnev’s part. He was also a man who liked guns and knew that what he killed he could eat and if he couldn’t eat it, well hell, these people were killed for their own good and the good of the cause.

It’s a bit vague how exactly Brezhnev came to see his first episode of The Rifleman, but I like to picture him in his silk pyjamas adorned with a selection of his finest medals reclining on his bed in some East European hotel room, possibly East Berlin, sipping vodka and cracking walnuts, while occasionally pointing a loaded finger at the TV screen and exclaiming, “Pew-pew…” as another villain bites the dust.

It’s a nice image. A friendly image. One that encapsulates much of Brezhnev’s style during his reign as Soviet President–self-indulgent, sometimes lazy, but with that ever-present threat of his sending out the KGB to have dissenters sent to the gulag.

Whether it’s America or Russia or the UK, there is something quite disturbing in the thought that so much power is gifted to one human by so many.

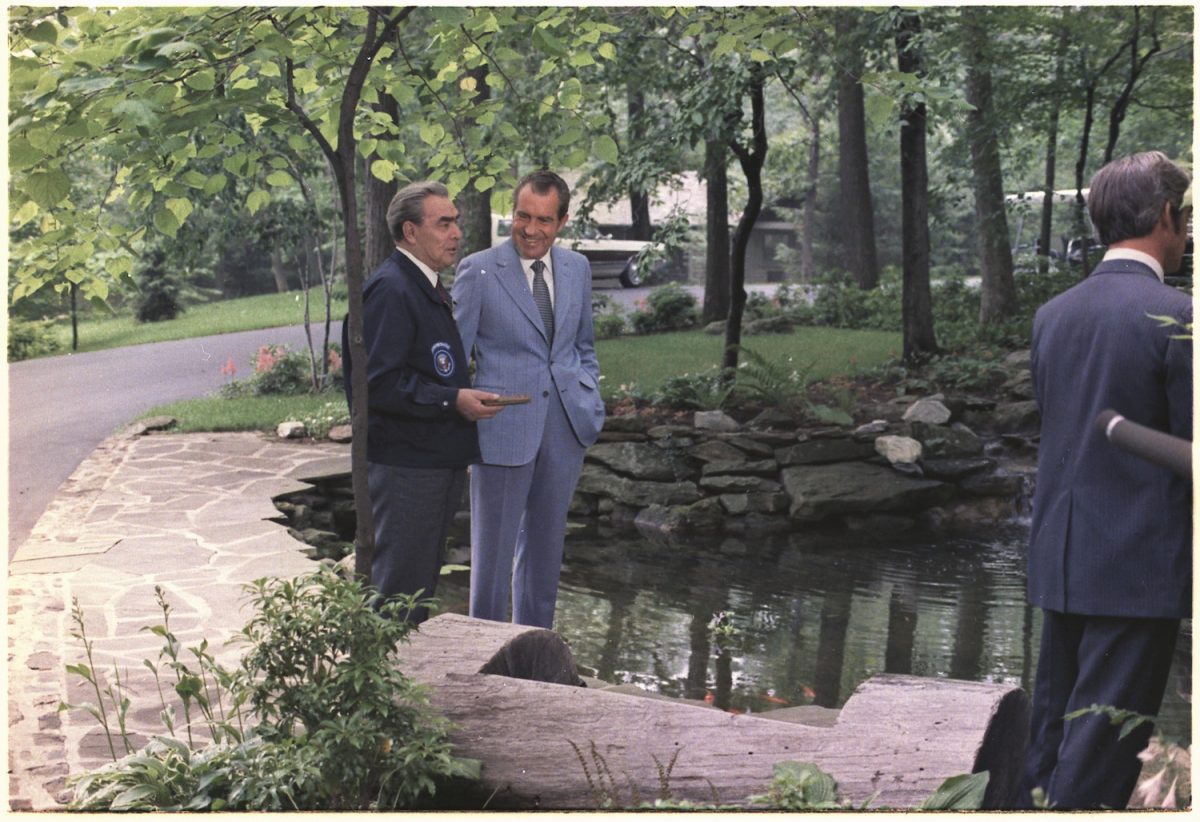

In June 1973, President Richard Nixon hosted a large party for Brezhnev, to which he invited a whole host of celebrities to meet (and no doubt impress) the Soviet leader. Chuck Connors was one of the many in attendance. The Whitehouse knew darn fine Brezhnev was a fan of Connors and his show The Rifleman.

According to one report, Whitehouse Press Secretary, Ron Ziegler, told Connors that “Brezhnev is a fan of yours,” and asked him “to do something” when he met him.

When Brezhnev met Connors he told him through his interpreter how big a fan he was of his work in particular his cowboy series. Connors smiled, shook Brezhnev’s hands warmly and said he would like to present him with a matching pair of Colt .45 revolvers on behalf of everyone who worked on The Rifleman.

The next day, a photo op was organised (natch..) for Connors to present Brezhnev with his Colt .45s. The Soviet President was delighted. Connors showed him how to twirl the pistols like a real gunslinger while Brezhnev told the actor he must come to the U.S.S.R. and make a cowboy movie.

Later, when Brezhnev was making his way to his plane, he spotted the tall lanky Connors standing among the crowd of well-wishes. Brezhnev ran across the tarmac and jumped into the actor’s arms who briefly lifted him off the ground. The image went global. It featured on the cover of some 1600 newspapers (apparently). This wasn’t just a hug of admiration, it became a symbol of the freedom American culture seemed to offer the world and the inevitable undoing of the U.S.S.R.

Yet, this worship of the American West was but a small deflection from the Watergate scandal which had engulfed the Presidency. Just over one year later, on 9th August 1974, President Richard Milhous Nixon resigned from office in disgrace.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.