“The comity of European peoples went to pieces when, and because, it allowed its weakest member to be excluded and persecuted.”

– Hannah Arendt, We Refugees, 1943

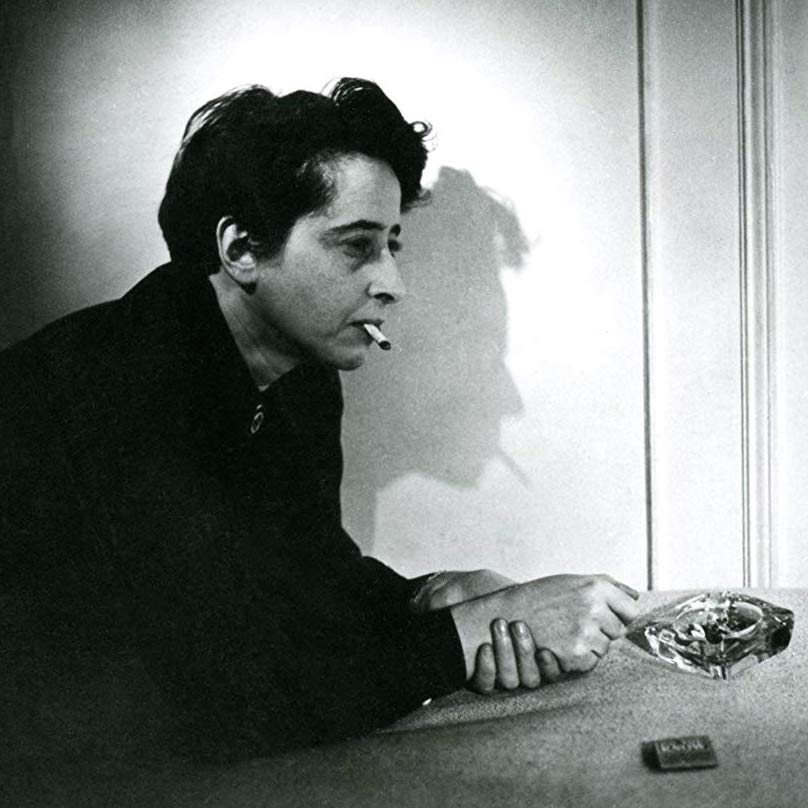

Hannah Arendt (October 14, 1906–December 4, 1975) was a German Jew who escaped the Holocaust, became an American citizen and saw some of the leading Nazis brought to trial at Nuremberg, as witnessed in her writing on the “banality of evil”. In January 43, she wrote We Refugees for the Jewish journal Menorah (1915–1962) about what is was to be a ‘Wandering Jew’ and live a life driven by escape, hope and need.

‘We Refugees’ by Hannah Arendt

In the first place, we don’t like to be called “refugees.” We ourselves call each other “newcomers” or “immigrants.” Our newspapers are papers for “Americans of German language”; and, as far as I know, there is not and never was any club founded by Hitler-persecuted people whose name indicated that its members were refugees.

A refugee used to be a person driven to seek refuge because of some act committed or some political opinion held. Well, it is true we have had to seek refuge; but we committed no acts and most of us never dreamt of having any radical opinion. With us the meaning of the term “refugee” has changed. Now “refugees” are those of us who have been so unfortunate as to arrive in a new country without means and have to be helped by Refugee Committees.

She considers when you stop being a refugee, become assimilated and carry the papers of social distinction:

Before this war broke out we were even more sensitive about being called refugees… We wanted to rebuild our lives, that was all. In order to rebuild one’s life one has to be strong and an optimist. So we are very optimistic.

You try to move on. You are told to forget:

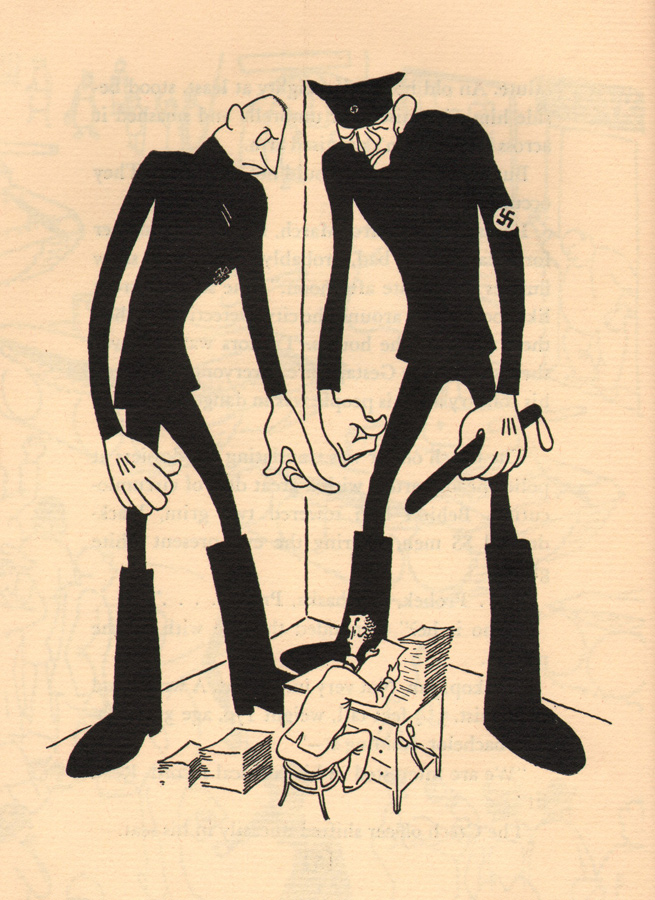

In order to forget more efficiently we rather avoid any allusion to concentration or internment camps we experienced in nearly all European countries — it might be interpreted as pessimism or lack of confidence in the new homeland. Besides, how often have we been told that nobody likes to listen to all that; hell is no longer a religious belief or a fantasy, but something as real as houses and stones and trees. Apparently nobody wants to know that contemporary history has created a new kind of human beings — the kind that are put in concentration camps by their foes and in internment camps by their friends…

From: The True Story of The Holocaust Train Rescued From The Heart of Darkness – Friday, April 13th, 1945

On Refugees and Suicide

What made you first remains. Arendt talks of dreams and memories of poems learned by heart. What is it about poetry that stays with us and can reach the soul?

Another Jewish survivor and refugee, Paul Celan (23 November 1920 – c. 20 April 1970), offered: “There is nothing in the world for which a poet will give up writing, not even when he is a Jew and the language of his poems is German.” Celan drowned in the River Seine in Paris. It may have been suicide.

In 1976, Austrian writer and refugee Jean Améry (31 October 1912 – 17 October 1978), who had been enslaved at Auschwitz, published the book On Suicide: A Discourse on Voluntary Death. He died by suicide via an overdose of sleeping pills in 1978.

Death is always present. You can try shrugging to get it off. But for some the weight is too heavy to bear. Realism bites, as Arendt writes:

No, there is something wrong with our optimism. There are those odd optimists among us who, having made a lot of optimistic speeches, go home and turn on the gas or make use of a skyscraper in quite an unexpected way. They seem to prove that our proclaimed cheerfulness is based on a dangerous readiness for death. Brought up in the conviction that life is the highest good and death the greatest dismay, we became witnesses and victims of worse terrors than death — without having been able to discover a higher ideal than life…

Instead of fighting — or thinking about how to become able to fight back — refugees have got used to wishing death to friends or relatives; if somebody dies, we cheerfully imagine all the trouble he has been saved. Finally many of us end by wishing that we, too, could be saved some trouble, and act accordingly.

Envying The Dead

To envy the dead was something that Jewish Italian writer and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi (31 July 1919 – 11 April 1987) contemplated, noting in The Periodic Table: “The things I had seen and suffered were burning inside of me; I felt closer to the dead than the living…” On April 11, 1987, Levi opened the door of his home in Turin, walked down the landing and fell from a third-story stairwell. The police report certified the suicide.

Ardent goes on:

Since 1938 — since Hitler’s invasion of Austria — we have seen how quickly eloquent optimism could change to speechless pessimism. As time went on, we got worse—even more optimistic and even more inclined to suicide. Austrian Jews under Schuschnigg were such a cheerful people—all impartial observers admired them. It was quite wonderful how deeply convinced they were that nothing could happen to them. But when German troops invaded the country and Gentile neighbours started riots at Jewish homes, Austrian Jews began to commit suicide.

Unlike other suicides, our friends leave no explanation of their deed, no indictment, no charge against a world that had forced a desperate man to talk and to behave cheerfully to his very last day. Letters left by them are conventional, meaningless documents. Thus, funeral orations we make at their open graves are brief, embarrassed and very hopeful. Nobody cares about motives, they seem to be clear to all of us.

…

Through their effort to save the statistical life of the Jewish people we know that Jews had the lowest suicide rate among all civilized nations. I am quite sure those figures are no longer correct, but I cannot prove it with new figures, though I can certainly with new experiences. This might be sufficient for those skeptical souls who never were quite convinced that the measure of one’s skull gives the exact idea of its content, or that statistics of crime show the exact level of national ethics. Anyhow, wherever European Jews are living today, they no longer behave according to statistical laws. Suicides occur not only among the panic-stricken people in Berlin and Vienna, in Bucharest or Paris, but in New York and Los Angeles, in Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

On the other hand, there has been little reported about suicides in the ghettoes and concentration camps themselves. True, we had very few reports at all from Poland, but we have been fairly well informed about German and French concentration camps.

Demons Teasing Me, Poster for the James Ensor Exhibition at the Salon des Cent in Paris – 1898 – print

We Must Find Meaning In Life

Albert Camus (November 7, 1913–January 4, 1960) talked of suicide, writing at the beginning of The Myth of Sisyphus

There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy. All the rest — whether or not the world has three dimensions, whether the mind has nine or twelve categories — comes afterwards.

…

I see many people die because they judge that life is not worth living. I see others paradoxically getting killed for the ideas or illusions that give them a reason for living (what is called a reason for living is also an excellent reason for dying). I therefore conclude that the meaning of life is the most urgent of questions.

Camus concludes that questioning is what we do and “the point is to live”. But some of us settle on a thought. As Arendt writes:

We are the first non-religious Jews persecuted — and we are the first ones who, not only in extremis, answer with suicide. Perhaps the philosophers are right who teach that suicide is the last and supreme guarantee of human freedom; not being free to create our lives or the world in which we live, we nevertheless are free to throw life away and to leave the world. Pious Jews, certainly, cannot realize this negative liberty: they perceive murder in suicide, that is, destruction of what man never is able to make, interference with the rights of the Creator…

Yet our suicides are no mad rebels who hurl defiance at life and the world, who try to kill in themselves the whole universe. Theirs is a quiet and modest way of vanishing; they seem to apologize for the violent solution they have found for their personal problems. In their opinion, generally, political events had nothing to do with their individual fate; in good or bad times they would believe solely in their personality. Now they find some mysterious shortcomings in themselves which prevent them from getting along. Having felt entitled from their earliest childhood to a certain social standard, they are failures in their own eyes if this standard cannot be kept any longer. Their optimism is the vain attempt to keep head above water. Behind this front of cheerfulness, they constantly struggle with despair of themselves. Finally, they die of a kind of selfishness.

She ends with a passage that rings true throughout the ages:

History has forced the status of outlaws upon both, upon pariahs and parvenus alike. The latter have not yet accepted the great wisdom of Balzac’s “On ne parvient pas deux fois”; thus they don’t understand the wild dreams of the former and feel humiliated in sharing their fate. Those few refugees who insist upon telling the truth, even to the point of “indecency,” get in exchange for their unpopularity one priceless advantage: history is no longer a closed book to them and politics is no longer the privilege of Gentiles. They know that the outlawing of the Jewish people in Europe has been followed closely by the outlawing of most European nations. Refugees driven from country to country represent the vanguard of their peoples — if they keep their identity. For the first time Jewish history is not separate but tied up with that of all other nations. The comity of European peoples went to pieces when, and because, it allowed its weakest member to be excluded and persecuted.

Source: Hannah Arendt, “We Refugees,” Menorah Journal 31, no. 1, January 1943.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.