Frida Kahlo (July 6, 1907 – July 13, 1954) and Diego Rivera (December 8, 1886–November 24, 1957) shared an unconventional and enduring love. In My Art, My Life: An Autobiography, a book that began as a newspaper article by American journalist Gladys March, Kahlo pays tribute to her lover. March commenced interviewing Rivera in 1944. She spent several months each year with the artist, eventually filling 2,000 pages with his recollections and interpretations of his art and life. It was not until a final manuscript had been checked by Rivera shortly before his death in 1957, that the book was finally published in 1960. The Appendix recounts statements made by Rivera’s four wives and/or live-in companions. Kahlo was “near death” when she met with March.

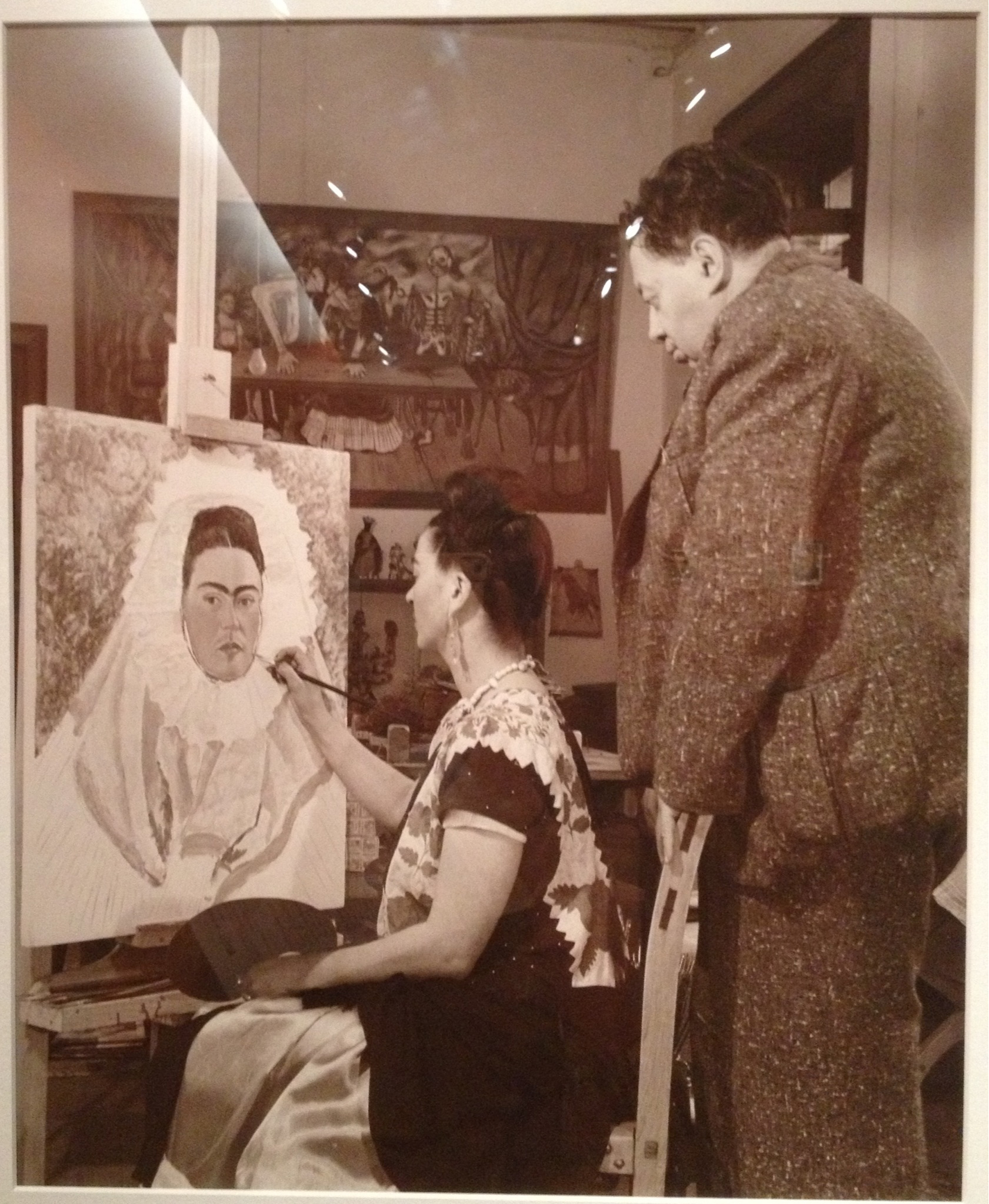

Diego En Mi Pensamiento – a self-portrait with Kahlo dressed in the traditional wedding attire of Tehuatepec women from Oaxaca, Mexico. In the center of her forehead is a portrait of Diego. It was completed in 1943 – after multiple affairs and their subsequent divorce and remarriage.

Frida’s words on Diego are frank to the point of brutal and mythic.

Statement by Frida Kahlo

I warn you that in this picture I am painting of Diego there will be colors which even I am not fully acquainted with. Besides, I love Diego so much I cannot be an objective speculator of him or his life… I cannot speak of Diego as my husband because that term, when applied to him, is an absurdity. He never has been, nor will he ever be, anybody’s husband. I also cannot speak of him as my lover because to me, he transcends by far the domain of sex. And if I attempt to speak of him purely, as a soul, I shall only end up by painting my own emotions. Yet considering these obstacles of sentiment, I shall try to sketch his image to the best of my ability.

Growing up from his Asiatic-type head is his fine, thin hair, which somehow gives the impression that it is floating in air. He looks like an immense baby with an amiable but sad-looking face. His wide, dark, and intelligent bulging eyes appear to be barely held in place by his swollen eyelids. They protrude like the eyes of a frog, each separated from the other in a most extraordinary way. They thus seem to enlarge his field of vision beyond that of most persons. It is almost as if they were constructed exclusively for a painter of vast spaces and multitudes. The effect produced by these unusual eyes, situated so far away from each other, encourages one to speculate on the ages-old oriental knowledge contained behind them.

On rare occasions, an ironic yet tender smile appears on his Buddha-like lips. Seeing him in the nude, one is immediately reminded of a young boy-frog standing on his hind legs. His skin is greenish-white, very like that of an aquatic animal. The only dark parts of his whole body are his hands and face, and that is because they are sunburned. His shoulders are like a child’s, narrow and round. They progress without any visible hint of angles, their tapering rotundity making them seem almost feminine. The arms diminish regularly into small, sensitive hands… It is incredible to think that these hands have been capable of achieving such a prodigious number of paintings. Another wonder is that they can still work as indefatigably as they do.

Diego’s chest — of it we have to say, that had he landed on an island governed by Sappho, where male invaders were apt to be executed, Diego would never have been in danger. The sensitivity of his marvelous breasts would have insured his welcome, although his masculine virility, specific and strange, would have made him equally desired in the lands of these queens avidly hungering for masculine love.

His enormous belly, smooth, tightly drawn, and sphere-shaped, is supported by two strong legs which are as beautifully solid as classical columns. They end in feet which point outward at an obtuse angle, as if moulded for a stance wide enough to cover the entire earth.

He sleeps in a foetal position. In his waking hours, he walks with a languorous elegance as if accustomed to living in a liquefied medium. By his movements, one would think that he found air denser to wade through than water.

I suppose everyone expects me to give a very feminine report about him, full of derogatory gossip and indecent revelations. Perhaps it is expected that I should lament how I have suffered living with a man like Diego. But I do not think the banks of a river suffer because they let the river flow, nor does the atom suffer for letting its energy escape. To my way of thinking, everything has its natural compensation.

To Diego painting is everything. He prefer his work to anything else in the world. It is his vocation and his vacation in one. For as long as I have known him, he has spent most of his waking hours at painting: between twelve and eighteen a day.

Therefore he cannot lead a normal life. Nor does he ever have the time to think what he does is moral, amoral, or immoral.

He has only one great social concern: to raise the standard of living of the Mexican Indians, who he loves so deeply. This love he has conveyed in painting after painting.

His temperament is invariably a happy one. He is irritated by only two things: loss of time from work – and stupidity. He has said many times he would rather have many intelligent enemies than one stupid friend.

Love is not blind. Love sees beauty and makes it shine.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.