John Ford was a great film director. A great American film director. He made some 140 films during his long, highly successful and multi-award-winning career. Half of them classics. Movies that could easily fill a good few chapters in any book on the history of cinema. Stagecoach, The Searchers, Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Rio Grande, The Grapes of Wrath, How Green Was My Valley, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance even Cheyenne Autumn.

Way too many to mention.

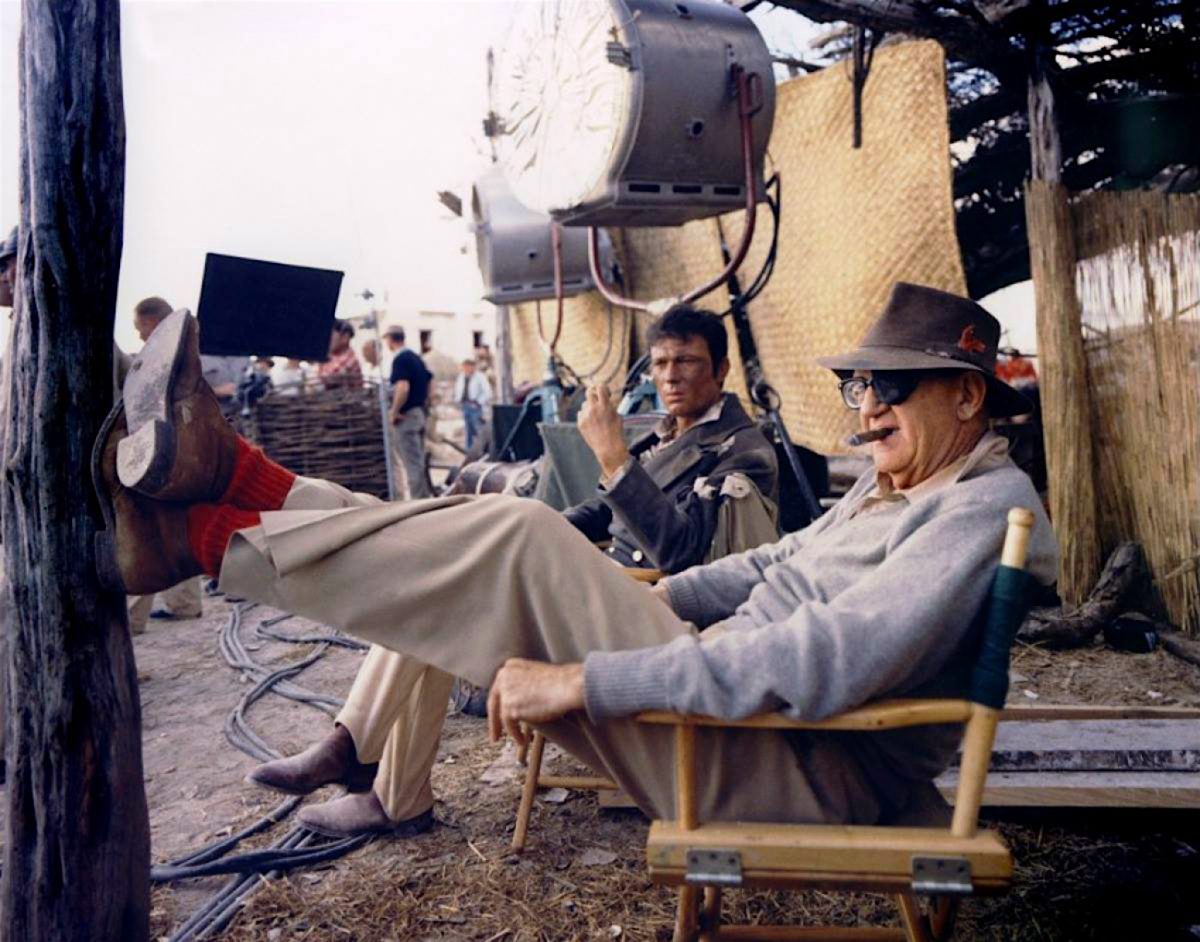

Movies was one thing. John Ford could pack a punch. He might have looked like a sap with a patch over one eye chewing on a handkerchief during takes–but Ford could pack a punch. A tough, two-fisted, son-of-an-Irish-immigrant, pipe-smoking booze-hound. He didn’t like saps. He didn’t like weakness. He didn’t care too much for studio types neither. During one film, he pulled a Hollywood exec. in front of a camera, “This is an associate producer,” he said, “Take a good look because you won’t be seeing him on this picture again.”

He wanted everyone to know he was a tough, no-nonsense son-of-a-bitch. He had a sneaking suspicion that making movies might make him seem slightly effete. To counter, fists would fly as the shot glasses clinked.

It was all a front.

Ford was in some swanky Hollywood restaurant, when a whiney sap came over mooching for dough. Ford was chinning whisky, chewing steak. The whiner was washing his hands, giving some soft-soap story about needing the money for his wife’s operation, just two hundred bucks, dig, so she can live. The more the sap talked, the more enraged Ford became. One eye looking in disgust, puffing on a pipe like Popeye, ready to roll up his sleeves. The sap was begging now, going down on one knee. Ford lashed out. Caught him hard on the face. The sap went flat out. Ford jumped up. Threw down his napkin in disgust. “How dare you come here like this?,” he yelled. “Who do think you are to talk to me in this way?” He stormed off. The sap gasping, grasping at the air to pull Ford back. For a second all the diners and staff at the restaurant had stopped. They clocked Ford. They clocked the sap. Ford slamming the restaurant door on the way out.

It left the right impression.

Outside the sap was pulled aside by some big lunk in a lean-cut suit. He was from John Ford. Told the sap to get in the car. Inside another lunk gave the sap a cheque for a thousand bucks. This guy was some manager flunkey called Totman. He said You’re wife’s gonna be fine, Mr. Ford has arranged a doctor to see her and an ambulance will take her to the best hospital. Ford paid for everything. He also bought the couple a house and pensioned them off out of his own pocket. The sap knew Ford was a good guy. Everyone else in that restaurant thought Ford a mean son-of-a-bitch.

According to John Gallagher in John Ford–The Man and His Movies, the actor John Baker who witnessed all of this knew that at:

Any moment, if that old actor had kept talking, people would have realized what a softy Jack is. He couldn’t have stood through that sad story without breaking down. He’s built this whole legend of toughness around himself to protect his softness.

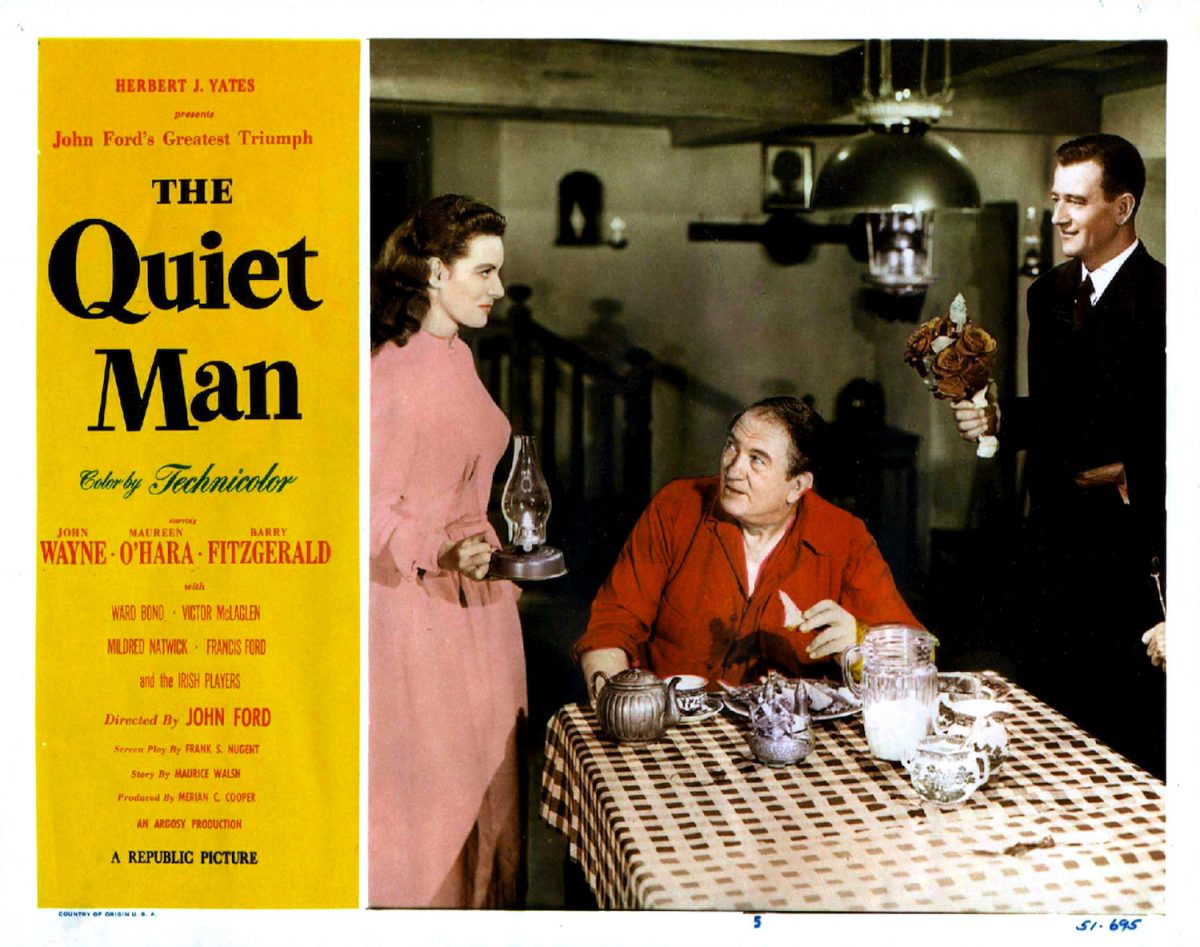

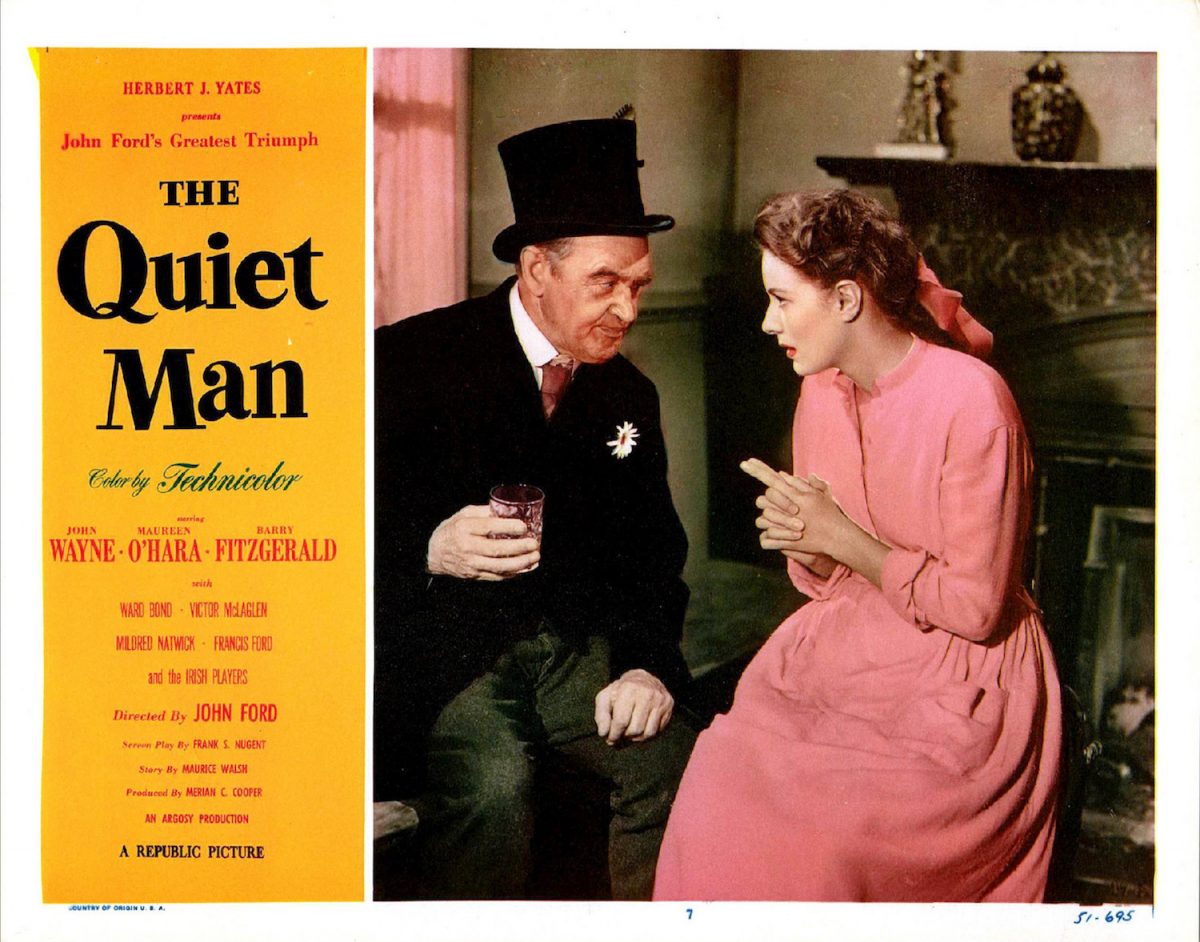

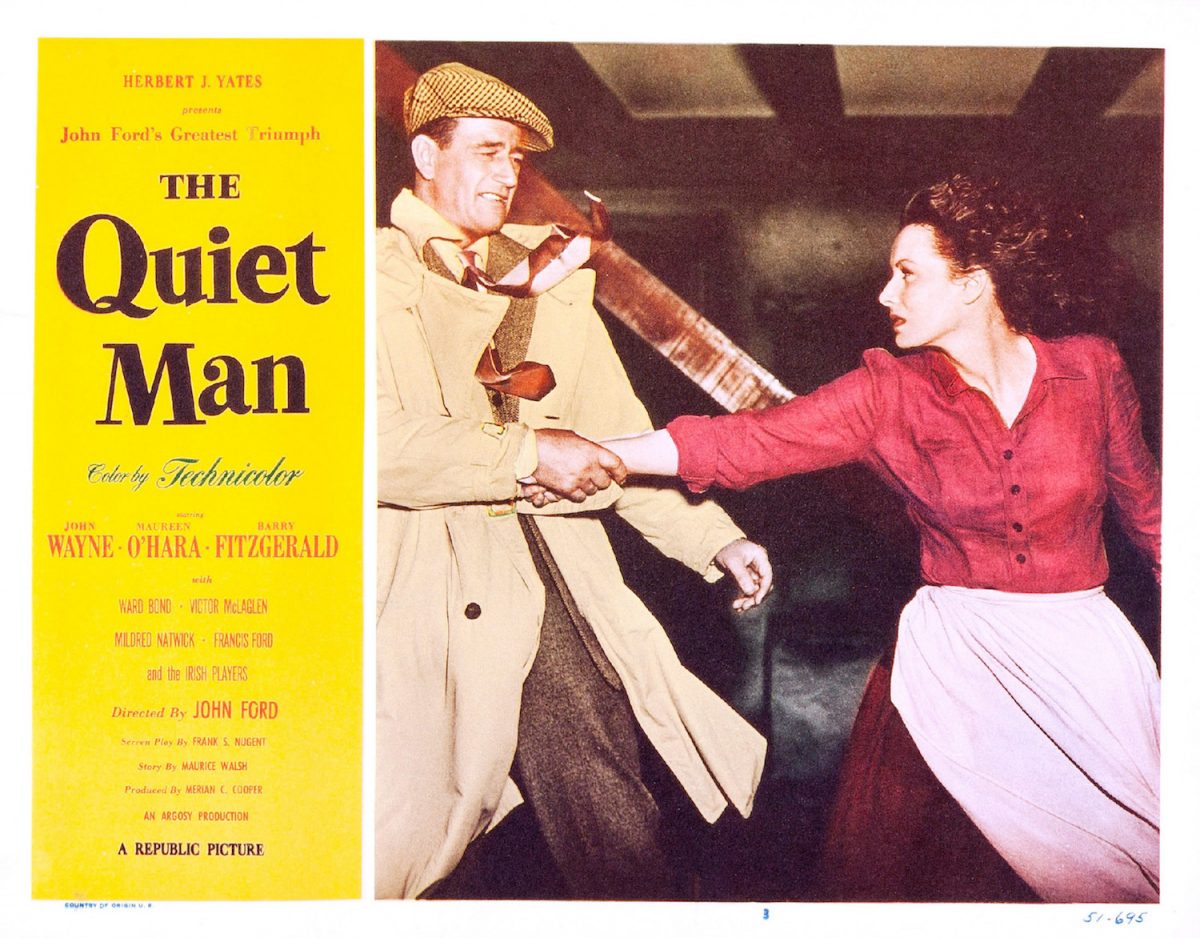

In 1950, Ford delivered Rio Grande to Republic Pictures. Republic was a low-budget, quick-turn-around B-movie western film company. Ford shot Rio Grande in 32 days, using 352 takes from 335 camera set-ups. The film starred John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara and made Republic a small fortune. Ford agreed to make the film on the proviso Republic financed his next feature The Quiet Man, a romantic comedy also starring Wayne and O’Hara.

The Quiet Man was based on a short story by Maurice Walsh, first published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1933. Ford optioned the story for ten bucks. For the next two decades, he hocked it around different studios. No one was interested until Republic agreed to make it.

Head of Republic Pictures, Herbert J. Yates hated the title The Quiet Man and wanted the film renamed The Prizefighter and the Colleen. Ford refused saying it gave the plot away.

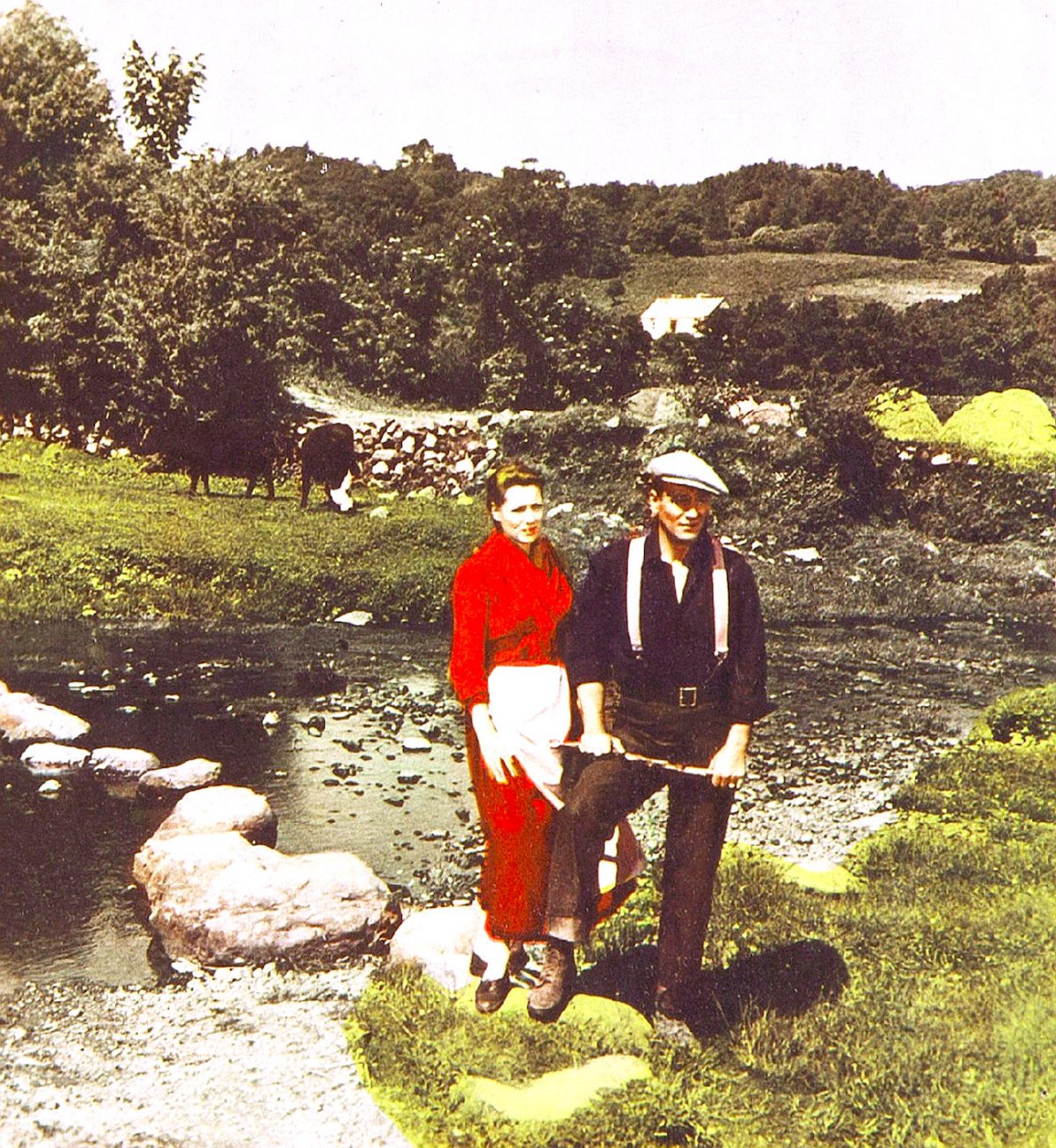

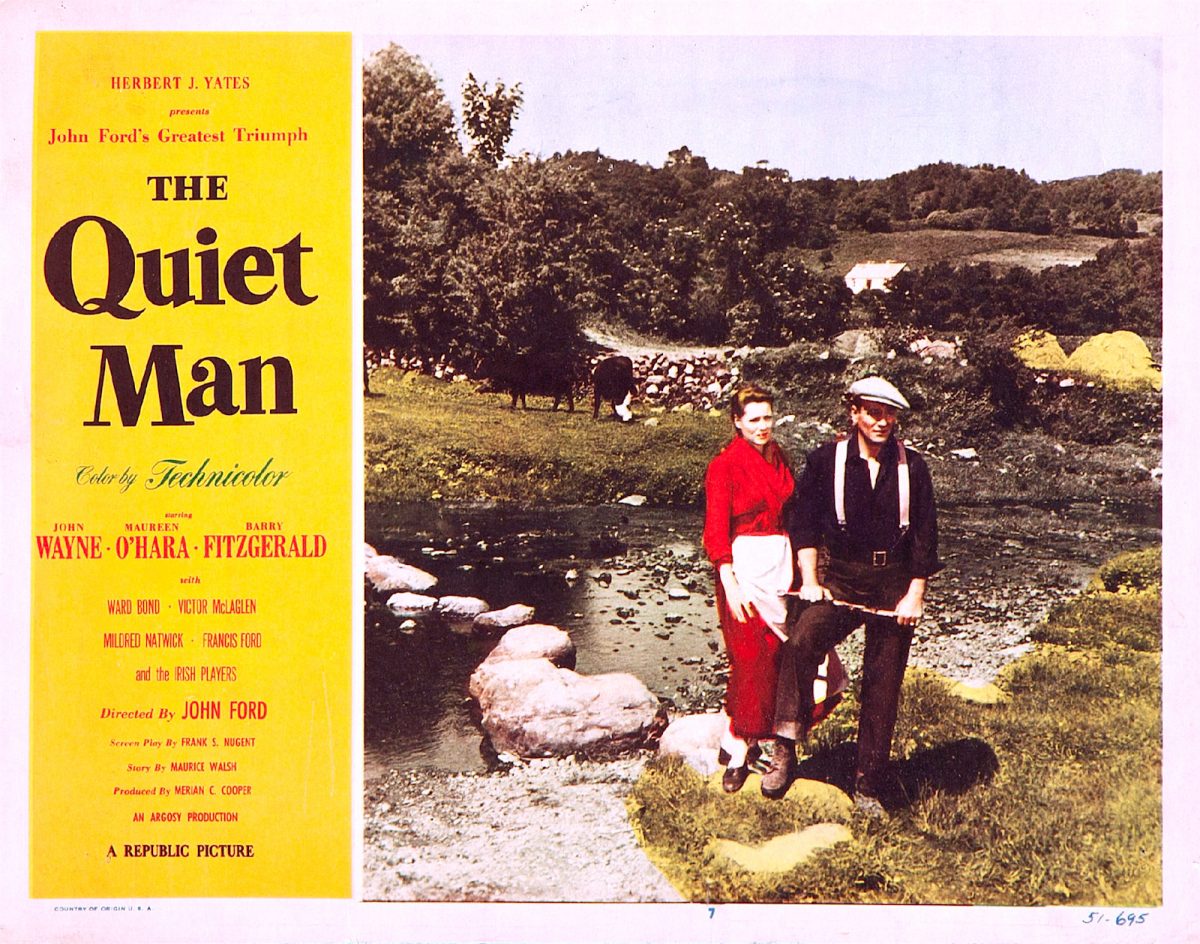

It was Republic’s first feature made abroad. It was also their most expensive costing $1.75 million. Filmed around the village of Cong, County Mayo, Ireland, The Quiet Man almost broke Ford. During filming he became unwell and told Wayne he had no idea whether he had a film, where it was going, or even if he could finish it. Ford took to his bed, while Wayne took over directing. Ford felt undermined working for such a low-budget, second-grade film company. Missing the action after a day in bed, Ford quickly returned to directing duties.

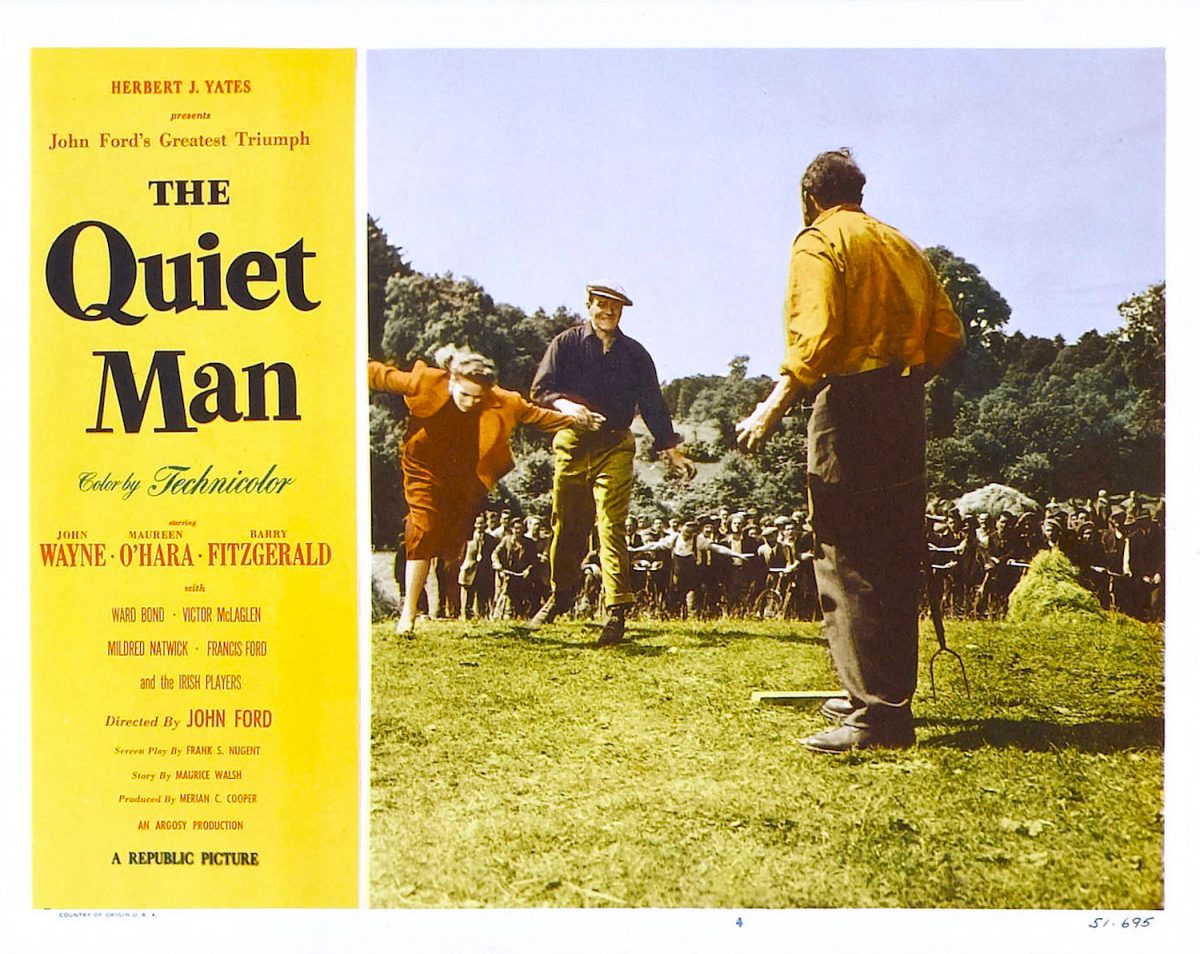

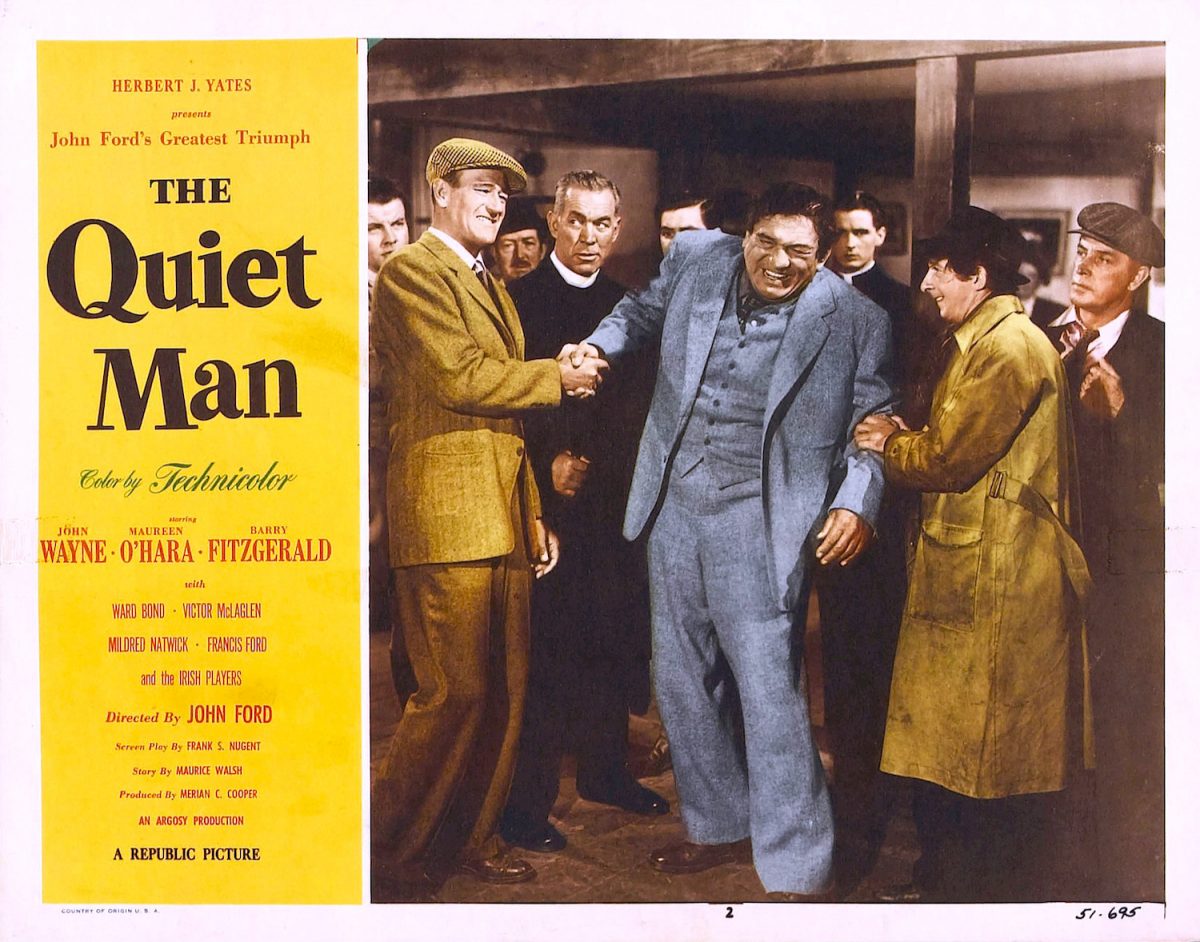

Despite difficulties, it was a happy experience for Wayne, O’Hara and Ford. Famed for its round-housing fist-fight between Wayne and Victor McLaglen, The Quiet Man was nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning two–best director for Ford and best cinematography for Winton C. Hoch and Archie Stout.

In 2013, The Quiet Man was selected for preservation at the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.