I dare… to tell the truth, with all the force born of the revulsion of an honest man, since the normal channels of justice have failed to do so.

– Émile Zola

The last years of novelist Émile Zola’s life were filled with upheaval. After a long career telling what he called “scientific” truths about poverty and working-class life in naturalist fiction, he put himself at risk by publishing his famous open letter to the president, J’Accuse!, on January 13, 1898 in defense of Jewish artillery officer Alfred Dreyfus. Three years earlier, Dreyfus been falsely accused, stripped of rank, and prosecuted for treason by an anti-Semitic right wing intent on using his case to advance their own interests.

“In the modern age of celebrity,” writes Caroline Moorehead at The Guardian, “it is easy to forget the heightened public attention once enjoyed by bestselling writers and commentators. Zola was then at the peak of his popularity, feted not only in France but in the English-speaking world.” The novelist was a hero to liberals and socialists alike in the cause to free Drefus, but “not everyone admired his earthy portrayals of the poor and the downtrodden in French society.” Henry James, for example, deplored what he called a “monstrous uncleanness” in Zola’s writing.

Street near Crystal Palace

Because of his fame and notoriety, Zola’s letter became an instant sensation. He had hoped to be prosecuted for libel so that new evidence would come to light, but the plan failed to exonerate Dreyfus, who remained imprisoned on Devil’s Island. In J’Accuse, Zola restates his commitment to rigorous honesty:

I dare… to tell the truth, with all the force born of the revulsion of an honest man, since the normal channels of justice have failed to do so. My duty is to speak out; I do not wish to be an accomplice in this travesty. My nights would otherwise be haunted by the spectre of the innocent man, far away, suffering the most horrible of tortures for a crime he did not commit.

After publishing the letter, Zola spent most of the final year of the 19th century exiled in England. When he first arrived, “in the cold and rain of an English winter,” Moorehead writes, he was 58 years old, “had no luggage and spoke no English and was unable to mime his way into buying new underpants.” Zola was vindicated in the summer of 1899 when the culprit in the Dreyfus case confessed and the military officer received a pardon. Zola returned in time to witness the historic 1900 Paris Exhibition, which he had anticipated in his letter as the “jewel that crowns this great century of labour, truth, and freedom.”

Once back in the beloved city of his birth, Zola began writing again and fully resumed the photography he first devoted himself to in 1894. He took pictures of the mechanical moving walkways of the Exhibition and the newly constructed Eiffel Tower. His photography is, by turns, a document of turn-of-the-century France and England and an intimate record of his family life. Zola approached photography with “a quasi-professional zeal and knowledge of photographic technique,” notes Introduction to the History of Photography.

He developed his own negatives and made enlargements as well as duly recorded experiments with materials and methods. His photographs document the artist’s private environment, his travels, family life, friends and his interest in all things modern as a witness to a changing world and to the developments of modern culture and of modern life.

[T]he master of literary description (a central element to his literary style and method) was also an original, confident and committed photographer who produced around seven thousand plates (of which only a few hundred have survived): images of the man and the artist, at the same time reflecting and being reflected by the times.

As in his fiction, Zola’s photography keeps both individuals and larger social structures in view—a challenge he posed to the modern artist in his theory of a “literature governed by science.” Zola was nominated for both the first and second Nobel Prizes for literature in 1901 and 1902, though he did not win. He died the year of his second nomination of presumably accidental carbon monoxide poisoning at his Paris home.

via Monovisions

Pont d’Iéna

Place Prosper-Goubaux, Paris

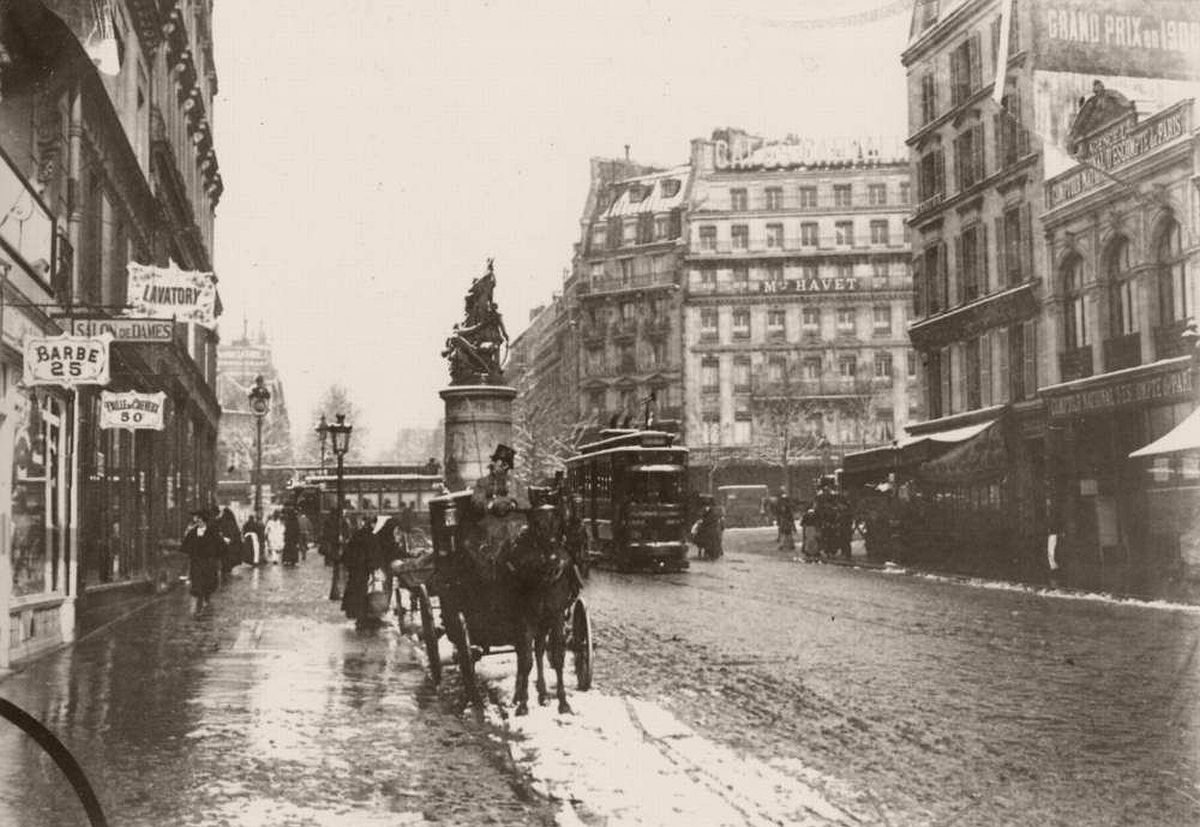

Place de Clichy

Open air cafe

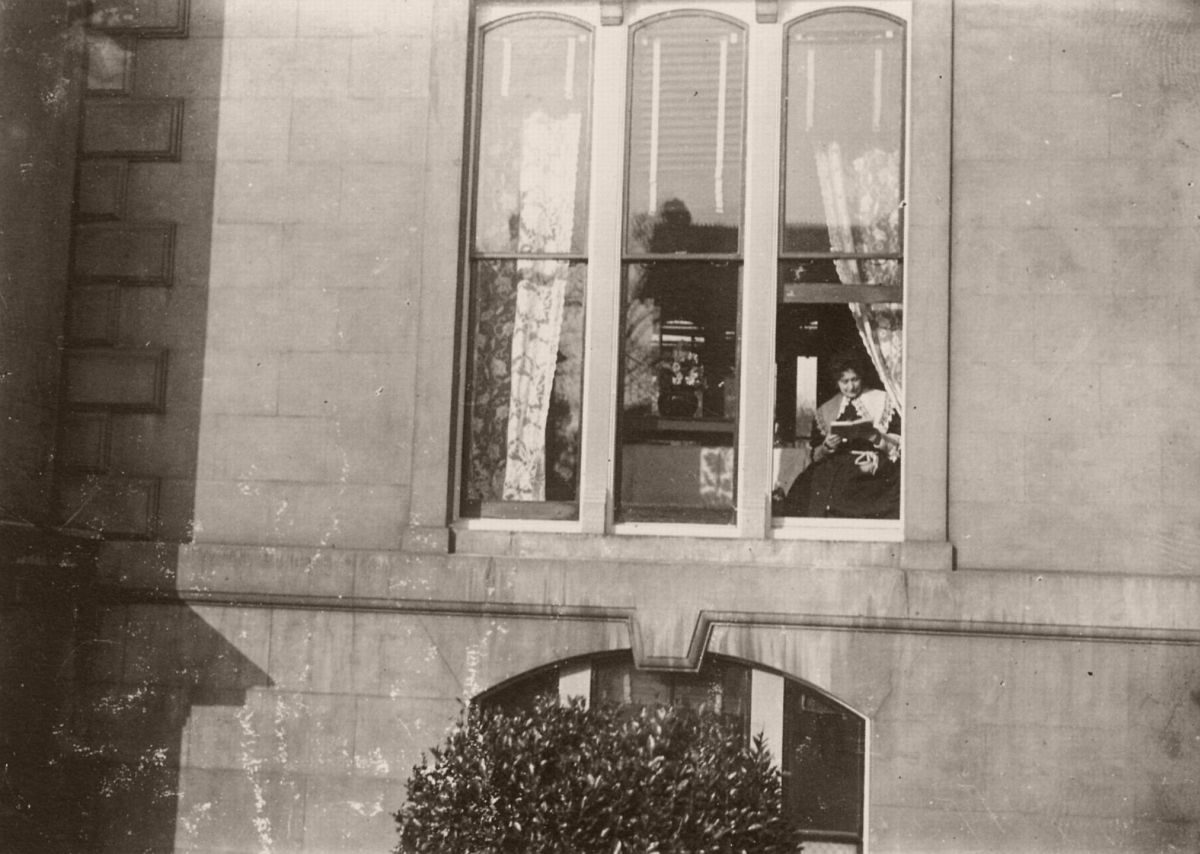

Mrs Zola in the Queen’s Hotel, Sydenham

Family portrait

After lunch

Place Prosper-Goubaux, Paris

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.