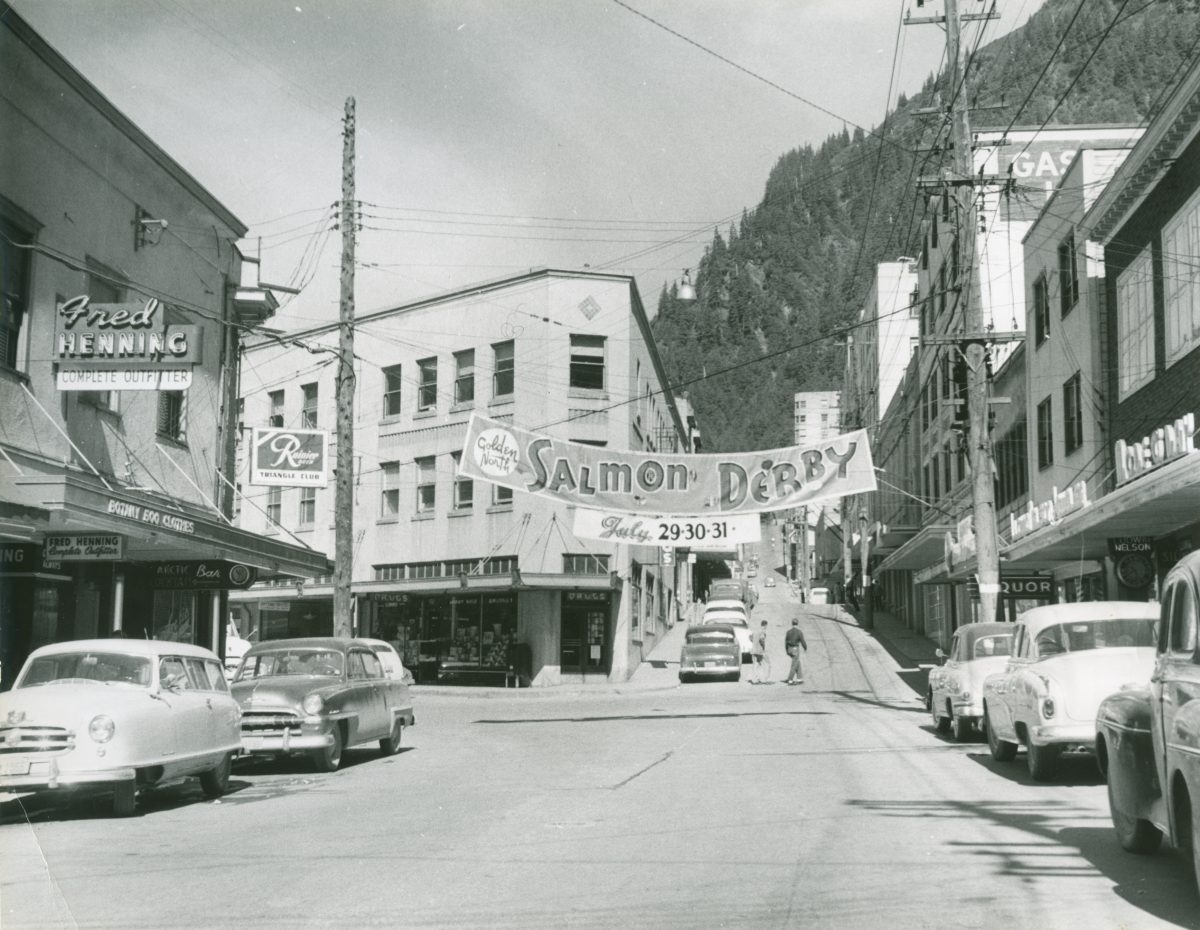

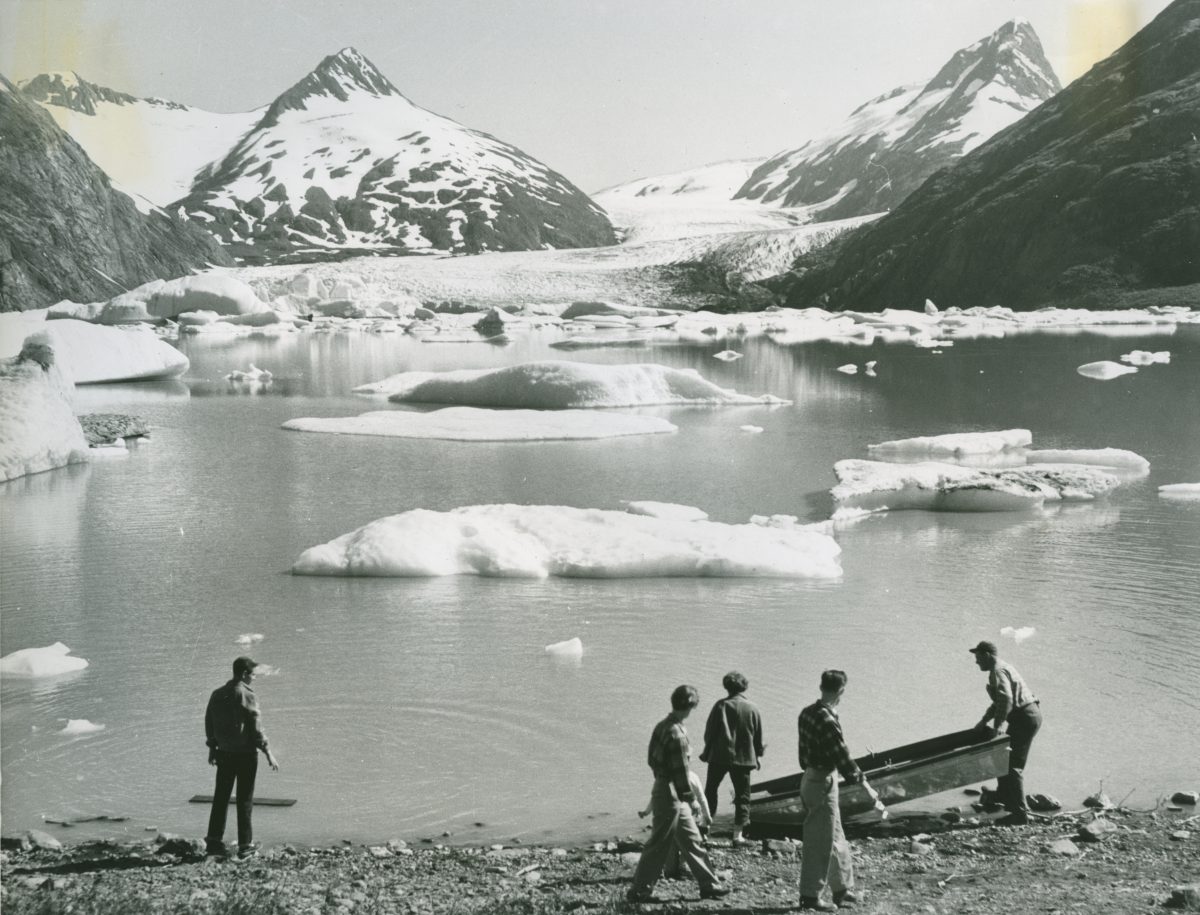

In 1955, Norwegian photojournalist Elisabeth Meyer (1899-1968) took a trip to Alaska. This was pioneer country. Anyone who landed at Fairbanks airport was met with the sign over the exit, known locally as the Law of the Yukon: “Send not your foolish and feeble – send me your strong and sane.”

A wealthy woman who had travelled widely, in 1929 Elisabeth had (as legend claims) become the first woman from the West to travel through Persia (now Iran), where photography without strict supervision by the state was outlawed. She was arrested on numerous occasions, and believed only her gender secured her freedom. In India she photographed Mahatma Gandhi, dined with Kemal Atatürk, first president or Turkey from 1923 until his death in 1938, and in Iraq interviewed King Faisal in his palace outside Baghdad.

Elisabeth Meyer: Photojournalist

Her passion for photography was cemented in 1929 when her father gave her a Kodak folding camera. Keen to develop her photography, she joined the Oslo Kamera Klubb, and remained active there until her death. The Klubb, which still exists, held most of her archive of 50,000 photographs, which it later donated to the country’s Preus Museum.

In 1937, she left Norway for Berlin to study photography at Albert Reimann’s School of Art and Design. In 1902, Reimann had founded teaching workshops for drawing, modelling, wood carving and metalworking, later known as the Schule Reimann, which he ran until 1935, initially escaping the Nazi dismissal of Jewish teachers as it was not applied to private schools. But at the end of 1935 he was forced to leave, and settled in London where his son opened the Reimann School and Studios in 1937. It was destroyed by German bombs in WW2.

In 1938, Meyer worked for Hungarian photographer Joszef Pécsi in Budapest.

She published her photographs in two travelogues – A woman’s journey to Persia (1930) and A woman’s journey through India (1933), as well as Norway in Pictures (1944), Look at Norway (1949) and the children’s book, Our Large and Small Animals in Pictures and Text (1950).

Elisabeth was working on a book on Indian culture and life in Alaska, Canada and Mexico at the time of her death.

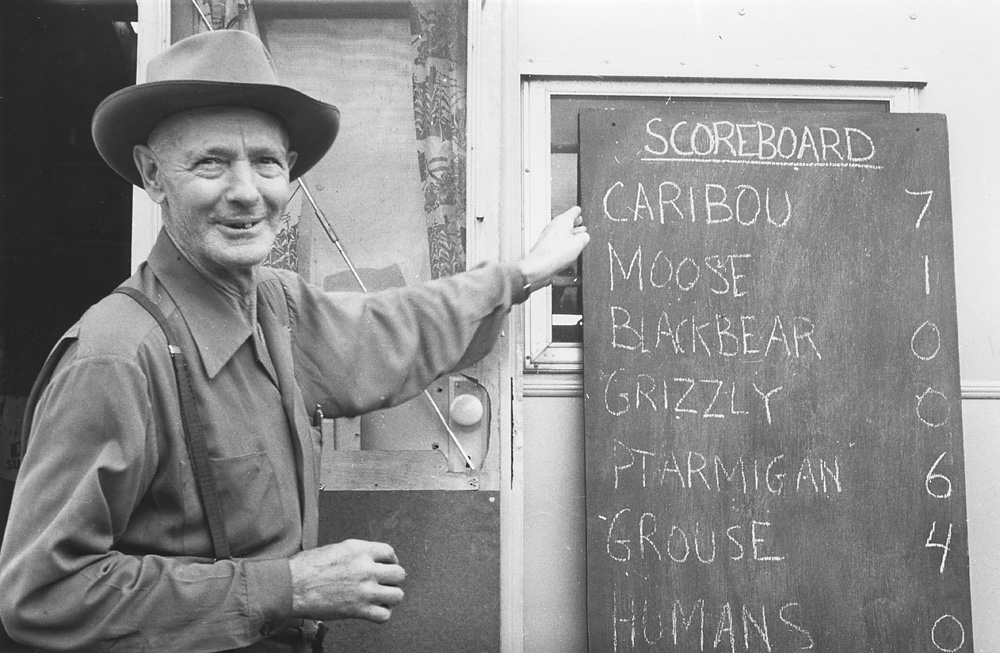

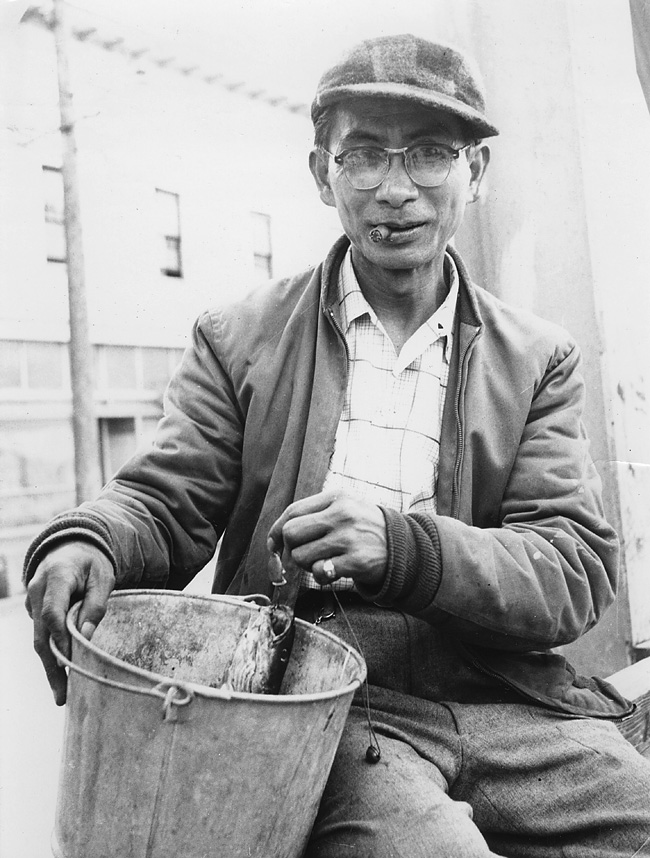

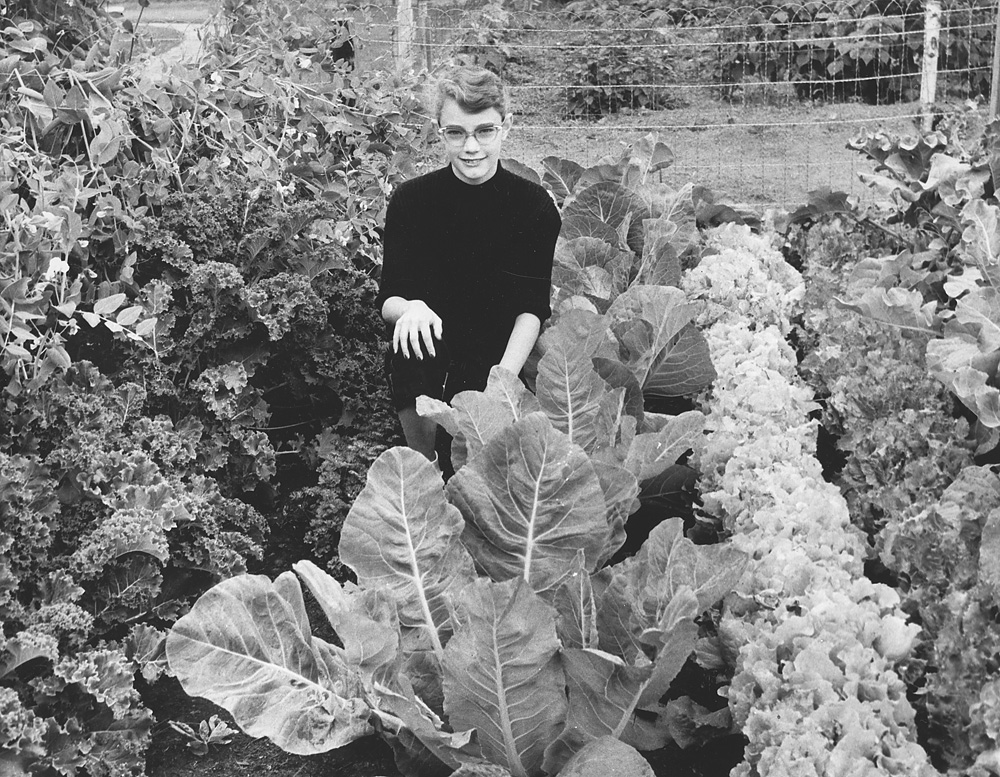

The Way It Was: Life in 1950s Alaska

To give more of an idea what life was like in 1950s Alaska, we can include an excerpt from the book, The Way It Was by Malachy Donoghue. This part (via Alaska Life) details the way Malachy arrived in Fairbanks, Alaska, from New York to work the gold fields for the United States Smelting, Refining and Mining Company.

When lunch was over I got on the truck and what a ride that was. You got up on the truck by grabbing hold of a big rope that had a large knot on the end of it and you swung up into the back end. The truck had two sides, a roof, and a bench on each side. You held onto anything you could grab. It was a fun, wild ride. The guys jumped off at whatever camp they were working at. I didn’t know where I was working and stayed on until I was the only one left. Eventually the truck came to a stop and Carl the foreman said, “Come with me.” I looked around and there was nobody in sight anywhere – I was in “No Man’s Land.” It sure was a long way from New York City.

He said, “OK, this is what I want you to do. Do you see the markings here on the ground – I want you to dig a hole approximately six feet long and about three feet wide and I want it four feet deep. There are picks and shovels over there.” He asked me if I thought I could do that and I said, “Sure, I don’t see any reason why I can’t.” He told me he was leaving but would be back later to pick me up. Before he left I asked him what the hole was for and he said, “That’s to bury a dead man.”

He again told me he would be back later to pick me up. I looked at the departing truck and wondered to myself, why would anyone want to bury someone in this ice?

There wasn’t a person anywhere and I couldn’t even see the camp. I realized that that wasn’t my problem. I had a hole to dig so I picked up the shovel and started to clear off the moss and debris from the marked area. Then I got the pick to loosen the surface soil and when the point of the pick hit the soil, it didn’t even leave a mark. I hit it again and again and nothing. I might as well be hitting a granite wall. This was my introduction to permafrost.

Later the truck returned and Carl came over to check my progress and said, “What are you trying to do, kill yourself?” Apparently the little that I got done, which was practically nothing, was much more than I should have accomplished. To this day I still wonder if that was an initiation test. I never was put on that detail again but that was my introduction to the gold fields.

We rode the truck to camp and I had my first dinner, which was delicious. I was told to go upstairs and wherever you find a room with an empty cot it’s yours. The rooms only had a metal cot in it with a mattress which you put your sleeping bag on and there was a small shelf for your personal possessions. Up the stairs to the left was a washroom which was about 8 or 9 feet wide and maybe 20 feet long. Along the wall was the wash area and there was a trough down the whole length of it, which had a tin galvanized liner inside and against the wall about every three feet was a hot and cold faucet where six or seven people could wash up at the same time.

They had a separate building for toilets and showers. I located a cot to put my sleeping bag on — no sheet or pillow and I didn’t realize at that time that I wouldn’t see any of those items for many years.

After staking my claim to my sleeping quarters, I went outside where a group of guys were standing around talking. They didn’t have anything else to do. I asked one of them if somebody had died in the camp and he said, “No, why do you ask?” I told them I had been digging a grave for someone and Carl Brenner said it was for a dead man. He started to laugh and I didn’t think it was funny when someone dies. He said, “You don’t know what a dead man is?” I thought it was when his heart stops and he stops breathing. He said, “Hell no, that’s not what it is. It isn’t a grave you were digging. Have you ever walked down a sidewalk and walked smack into a cable coming from a pole on an angle to the ground? Well, that cable has to be attached to something in the ground and it’s attached to a dead man which is usually a large chunk of wood about 2 feet by 5 feet, buried in the soil to support it. So there is no wake and no funeral.”

Wow, the things you learn. Learning happens fast in Alaska.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.