“At worst one is in motion; and at best

Reaching no absolute, in which to rest

One is always nearer by not keeping still.”

– Thom Gunn

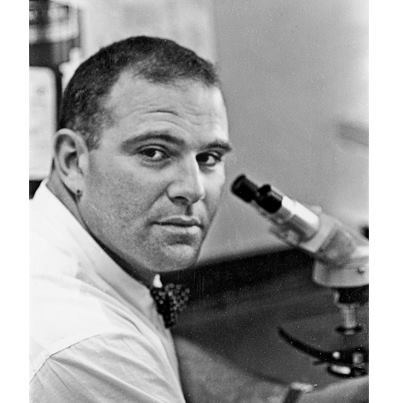

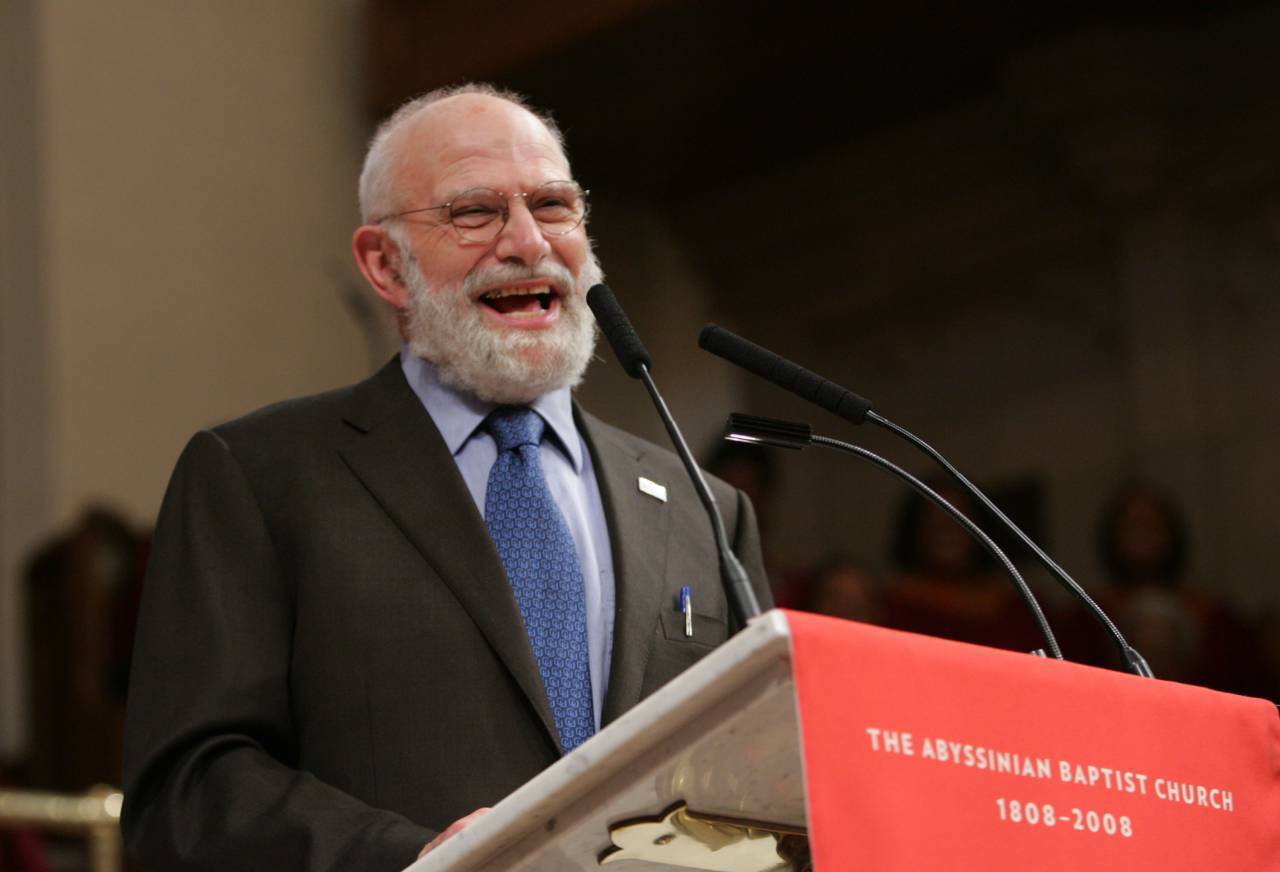

NEW YORK, NY – MAY 31: Dr. Oliver Sacks speaks at the “Music & the Brain” presentation at the Abyssinian Church at the World Science Festival on May 31, 2008 in New York City. (Photo by Thos Robinson/Getty Images for World Science Festival)

Dr. Oliver Sacks wants to share memories of his younger days. The British neurologist, gay biker (nickname: ‘Wolf’), one time holder of the Californian squat-thrust record and drug adventurer (“All other motives, goals, interests, desires disappeared in the vacuousness of the ecstasy”) tells us much in his memoir On The Move.

I first encountered Sacks in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (1985), his collection of case studies of peculiar illnesses; the title taken from a patient with visual agnosia, unable to recognize objects and people. Through Sacks’ writing, we get to move behind the man’s eyes, seeing the wife and the hat from his perspective. We get to care about him.

Sacks’s editor warned him that his first book — a 1970 study of migraines — was “too easy to read. This will make people suspicious — professionalise it.” The man was a fool. Sacks stuck to his task. In 1973 Awakenings was published. Through Sacks’ sharp wit we got to understand the patients at New York’s Beth Abraham hospital, survivors of a forgotten 1920 epidemic of sleepy sickness.

Sacks’ gift is to make us care about the people he treats and observes, to substantiate their inner workings. He makes the invisible glow and hum. We care. And we care about Sacks.

In February 2015, Sacks discovered that he had terminal cancer and had months to live. This book will be his last.

Of course, it’s a literary work. Can we believe it all as true? According to his friend, the doctor and director Jonathan Miller: “Oliver has aspects of a Borgesian fantasist. He remembers things that never happened.”

And though we enjoy the photographs of Dr Sacks, we recall him telling us that he is ‘face blind’:

I am particularly thrown if I see people out of context, even if I have been with them five minutes before. This happened one morning just after an appointment with my psychiatrist. (I had been seeing him twice weekly for several years at this point.) A few minutes after I left his office, I encountered a soberly dressed man who greeted me in the lobby of the building. I was puzzled as to why this stranger seemed to know me, until the doorman greeted him by name—it was, of course, my analyst. (This failure to recognize him came up as a topic in our next session; I think that he did not entirely believe me when I maintained that it had a neurological basis rather than a psychiatric one.)

His autobiography promises to be different to most others.

On social situations, he writes:

I am shy in ordinary social contexts; I am not able to “chat” with any ease; I have difficulty recognizing people (this is lifelong, though worse now my eyesight is impaired); I have little knowledge of and little interest in current affairs, whether political, social, or sexual. Now, additionally, I am hard of hearing, a polite term for deepening deafness. Given all this, I tend to retreat into a corner, to look invisible, to hope I am passed over. This was incapacitating in the 1960s, when I went to gay bars to meet people; I would agonize, wedged into a corner, and leave after an hour, alone, sad, but somehow relieved. But if I find someone, at a party or elsewhere, who shares some of my own (usually scientific) interests — volcanoes, jellyfish, gravitational waves, whatever — then I am immediately drawn into animated conversation…

I almost never speak to people in the street. But some years ago, there was a lunar eclipse, and I went outside to view it with my little 20x telescope. Everyone else on the busy sidewalk seemed oblivious to the extraordinary celestial happening above them, so I stopped people, saying, “Look! Look what’s happening to the moon!” and pressing my telescope into their hands. People were taken aback at being approached in this way, but, intrigued by my manifestly innocent enthusiasm, they raised the telescope to their eyes, “wowed,” and handed it back. “Hey, man, thanks for letting me look at that,” or “Gee, thanks for showing me.”

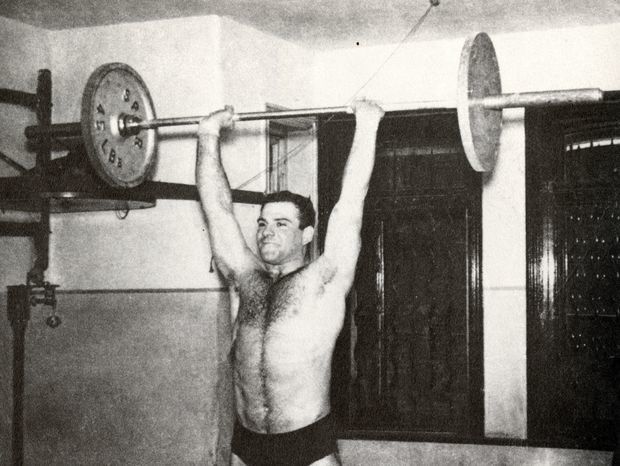

!["A full squat with 600 pounds, a California state record [Dr. Sacks] set in 1961." (On The Move: A Life/Knopf)](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/oliver-sachs.jpg)

“A full squat with 600 pounds, a California state record [Dr. Sacks] set in 1961.”

(On The Move: A Life/Knopf)

On the constant self, he says:

I sometimes wonder why I pushed myself so relentlessly in weight lifting. My motive, I think, was not an uncommon one; I was not the ninety-eight-pound weakling of bodybuilding advertisements, but I was timid, diffident, insecure, submissive. I became strong—very strong—with all my weight lifting but found that this did nothing for my character, which remained exactly the same.

On the human experience, he writes:

At UCLA, we residents had a weekly ‘Journal Club’; we would read the latest papers in neurology and discuss them. I sometimes annoyed the group, I think, by saying that we should also discuss the writings of our nineteenth-century forebears, relating what we were seeing in patients to their observations and thoughts. This was seen by the others as archaism; we were short of time, and we had better things to do than consider such ‘obsolete’ matters. This attitude was reflected, implicitly, in many of the journal articles we read; they made little reference to anything more than five years old. It was as if neurology had no history.

I found this dismaying, for I think in narrative and historical terms. As a chemistry-mad boy, I devoured books on the history of chemistry, the evolution of its ideas, and the lives of my favorite chemists. Chemistry had, for me, a historical and human dimension too.

He says on moving not escaping:

I sometimes wonder why I have spent more than fifty years in New York, when it was the West, and especially the Southwest, which so enthralled me. I now have many ties in New York—to my patients, my students, my friends, and my analyst—but I have never felt it move me the way California did. I suspect my nostalgia may be not only for the place itself but for youth, and a very different time, and being in love, and being able to say, ‘The future is before me.’

Perhaps the most painful section deals with intimacy. His surgeon mother was not his rock.

“You don’t seem to have many girlfriends,” he said. “Don’t you like girls?”

“They’re all right,” I answered, wishing the conversation would stop.

“Perhaps you prefer boys?” he persisted.

“Yes, I do — but it’s just a feeling — I have never ‘done’ anything,” and then I added, fearfully, “Don’t tell Ma — she won’t be able to take it.” But my father did tell her, and the next morning she came down with a face of thunder, a face I had never seen before. “You are an abomination,” she said. “I wish you had never been born.” Then she left and did not speak to me for several days. When she did speak, there was no reference to what she had said (nor did she ever refer to the matter again), but something had come between us.

He empathised.

We are all creatures of our upbringings, our cultures, our times. And I have needed to remind myself, repeatedly, that my mother was born in the 1890s and had an Orthodox upbringing and that in England in the 1950s homosexual behavior was treated not only as a perversion but as a criminal offense. I have to remember, too, that sex is one of those areas — like religion and politics — where otherwise decent and rational people may have intense, irrational feelings.

My mother did not mean to be cruel, to wish me dead. She was suddenly overwhelmed, I now realize, and she probably regretted her words or perhaps partitioned them off in a closeted part of her mind. But her words haunted me for much of my life and played a major part in inhibiting and injecting with guilt what should have been a free and joyous expression of sexuality.

Sacks was not alone. There was one of his mother’s six sisters, Aunt Lennie (nee Helena Penina Landau in 1892). The founder of the wonderfully named Jewish Fresh Air School for Delicate Children, was an ally:

I felt very loved by her, and I loved her intensely too, and this was a love without ambivalence, without conditionality. Nothing I could say could repel or shock her; there seemed no limit to her powers of sympathy and understanding, the generosity and spaciousness of her heart…

She had felt, since my boyhood days, that I could and should be “a writer.”

So. He wrote:

I am much enjoying Seed and like its whole format — the cover design, the luxurious paper, the lovely print, and the feeling for words that all you contributors have, whether grave or gay. . . . Will you be dismayed when I say how gloriously young (and of course vital) you all are.

They exchanged letters. Lennie was a fan of the mensch:

I received your amazing excerpts from your journals. I found the whole thing breathtaking. I was suddenly conscious that I was gasping physically.

Lennie helped to fill the void of motherly love. Her missives could be entitled ‘My nephew the doctor’:

You’ve got so much in your favour — brains, charm, presentability, a sense of the ridiculous, and a whole gaggle of us who believe in you… Len’s belief in me had been important since my earliest years, since my parents, I thought, did not believe in me, and I had only a fragile belief in myself.

In 1978, as Lennie lay dying, Sacks wrote her a letter:

Dearest Len,

We have all of us been hoping so intensely that this month would see your return to health; but, alas! this was not to be.

My heart is torn when I hear of your weakness, your misery — and, now, your longing to die. You, who have always loved life, and been such a source of strength and life to so many, can face death, even choose it, with serenity and courage, mixed, of course, with the grief of all passing. We, I, can much less bear the thought of losing you. You have been as dear to me as anyone in this world.

I shall hope against hope that you may weather this misery, and be restored again to the joy of full living. But if this is not to be, I must thank you — thank you, once again, and for the last time, for living — for being you.

Love, Oliver

Love. You can feel it in everything Sacks writes.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.

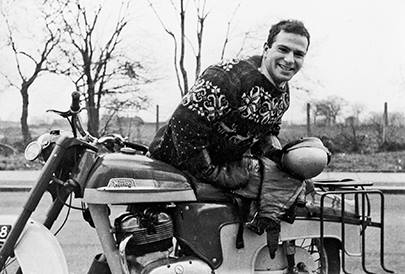

!["In Greenwich Village, 1961, on [his] new BMW R60."(On The Move: A Life/Knopf)](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/oliver-sachs-2.jpg)