“Ho visto Maradona…” (I saw Maradona)

– Napoli fan explaining to your writer over dinner the greatest thing he’d ever seen

Diego Maradona (30 October 1960 – 25 November 2020) was the greatest footballer of all time. He was a true national hero. To mark his death, Argentina has declared three days of mourning.

Maradona was possessed of a sublime blend of rough desire and divine talent, qualities no more in evidence than in Argentina’s match with England in the quarter-final of the Mexico ’86 World Cup. After the “Hand of God” goal, in which he clearly punched the ball into the English net, Maradona scored one of the best goals of all time, slicing and burrowing through the England team at the Azteca stadium to take the game 2-1. The then England manager Bobby Robson called that second goal a “bloody miracle”.

In Argentina, they like the first one best.

1986 World Cup – Quarter Final – Argentina v England – Mexico City – 22 Jun 1986. Maradona scoring the ‘Hand of God’ goal

FIFA World Cup – Mexico – 22.6.1986, Estadio Azteca, Mexico, D.F. – Quarter-final Argentina v England.

Diego Maradona celebrates in front of the England fans after scoring the greatest goal the World Cup has ever seen.

Around four years earlier, the United Kingdom and Argentina had fought in The Falklands Conflict, a 10-week undeclared war over two British dependent territories in the south Atlantic. The fighting began on 2 April, when Argentina invaded and occupied the Falkland Islands, followed by the invasion of South Georgia the next day. The conflict lasted 74 days and ended with an Argentine surrender on 14 June, returning the islands to British control.

“In the pre-match interview we had all said that football and politics shouldn’t be confused, but that was a lie. We did nothing but think about that. Bollocks was it just another match!” Maradona wrote in his autobiography. Of the second goal he noted: “I wanted to put the whole sequence in stills, blown up really big, above the headboard of my bed”. And of the first: “I got a lot of pleasure from the other goal as well. Sometimes I think I almost enjoyed that one more. They both had their own charm.”

Two goals. Two fingers. Up yours Inglaterra!

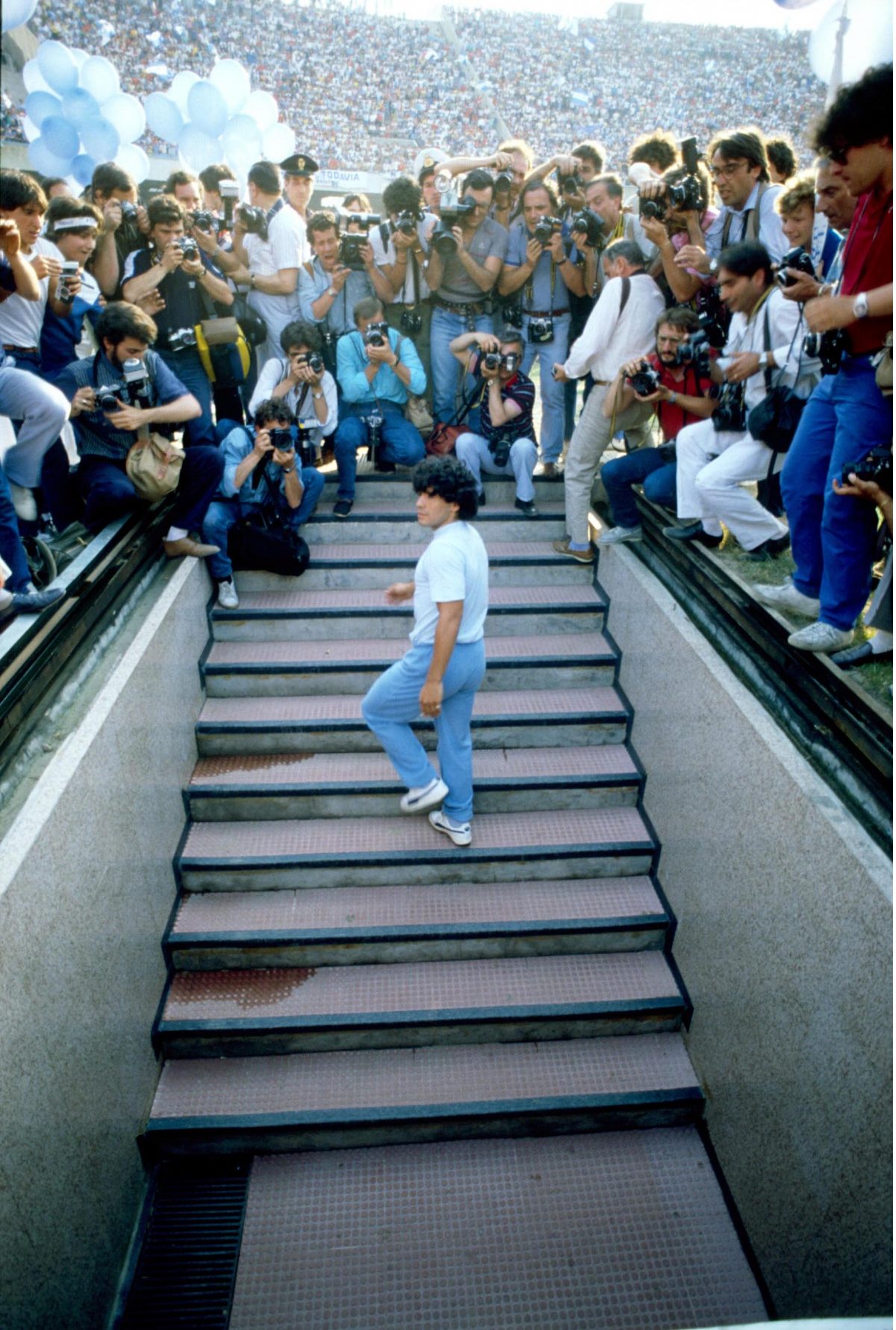

Photo by Vittorio La Verde : Maradona arriving at San Paolo Stadium after signing for Napoli – 05 Jul 1984

At Napoli, he led the unfashionable southern club their first Serie A title in 1987 and another in 1990, alongside an Italian Cup in 1987 and a Uefa Cup in 1989. In Naples he shone and was damaged. The cocaine he’d begun to take in Spain now took a firmer grip. At the 1990 World Cup he used a plastic penis and a fake bladder filled with somebody else’s urine to beat a drugs test. He was banned for drugs use (cocaine) in 1991 and was kicked out of the World Cup in the USA after testing positive for ephedrine.

Maradona (middle) with Queen during the rock band’s 1981 South American tour

But the drugs will not be the story we will remember Maradona by when the showreels are played. This was the boy from the slums many of his countrymen saw as untermensch who rose to the top. “Diegito,” shouted his uncle Cirilo as he helped the very young Maradona from a cesspit he’d slipped into by the family home his father had fashioned from loose bricks and corrugated iron in the Buenos Aires barrio Villa Fiorita (“little bloom”), “keep your head above the shit.”

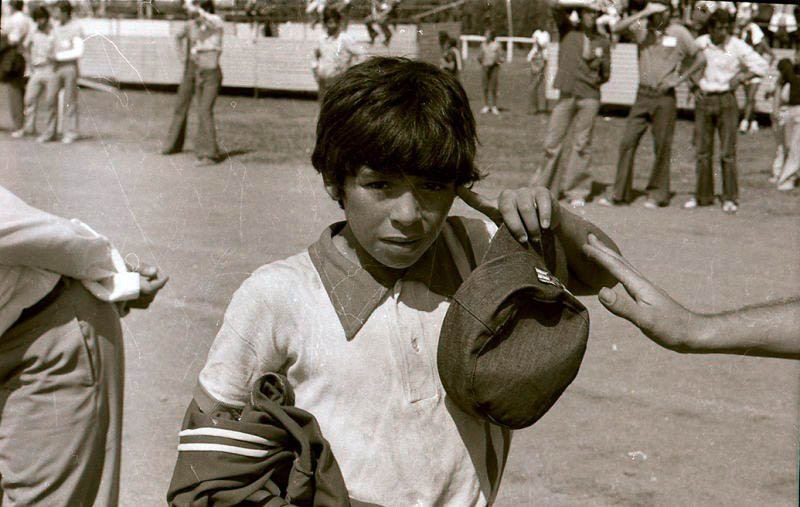

He learned to play in the potreros, the hard, vacant lots of the slums, where skills were not enough to survive. You needed to mark your turf. Maradona was memorable in the flesh (and how that flesh bloomed in the later yers), but in slow motion he was hard as iron and gave no quarter.

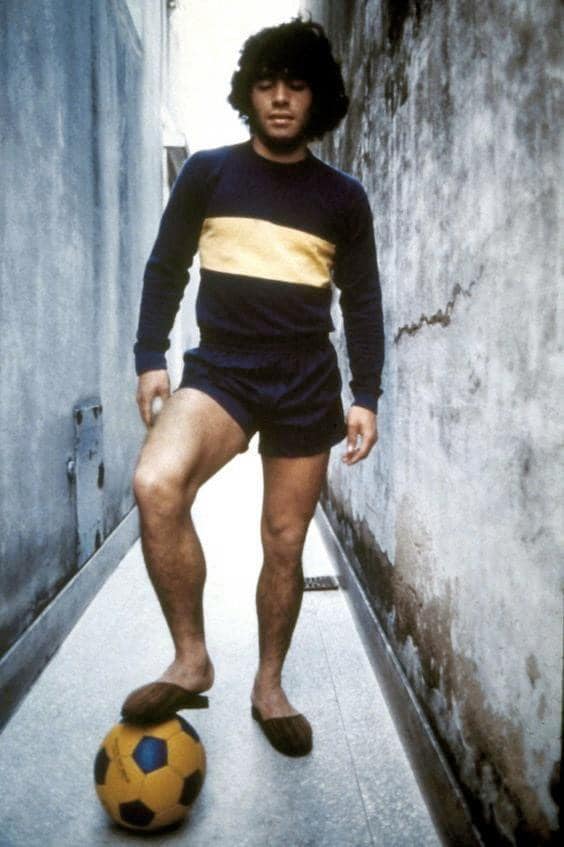

His playing record is phenomenal. He first played for Los Cebollitas (Little Onions), a youth team of Argentinos Juniors, making his debut for the senior side before his 16th birthday. On 27 February 1977, Maradona made his debut for Argentina, coming on as a 65th-minute substitute in a friendly against Hungary at La Bombonera. In 1981 he helped Boca Juniors win the Argentine title. In 1982, he joined Barcelona for a then world record fee of £5m. A failure to settle and a broken angle led to him being shipped out in 1984 to Napoli. And then he came good. And how…

Maradona playing at the Torneos Evita in 1973 (a national sporting event in Argentina) with the “Cebollitas”

Maradona’s most famous nutmeg, the day he debuted in Primera División, 20 October 1976

Maradona embodied the Argentine identity.

As Jonathan Wilson notes, Borocotó (aka Ricardo Lorenzo), a journalist at the Bueno Aires newspaper El Gráfico, wrote in 1928 that any statue erected to the soul of the Argentinian game would depict “a pibe [urchin] with a dirty face, a mane of hair rebelling against the comb; with intelligent, roving, trickster and persuasive eyes and a sparkling gaze that seem to hint at a picaresque laugh that does not quite manage to form on his mouth, full of small teeth that might be worn down through eating yesterday’s bread.

“His trousers are a few roughly sewn patches; his vest with Argentinian stripes, with a very low neck and with many holes eaten out by the invisible mice of use … His knees covered with the scabs of wounds disinfected by fate; barefoot or with shoes whose holes in the toes suggest they have been made through too much shooting. His stance must be characteristic; it must seem as if he is dribbling with a rag ball.”

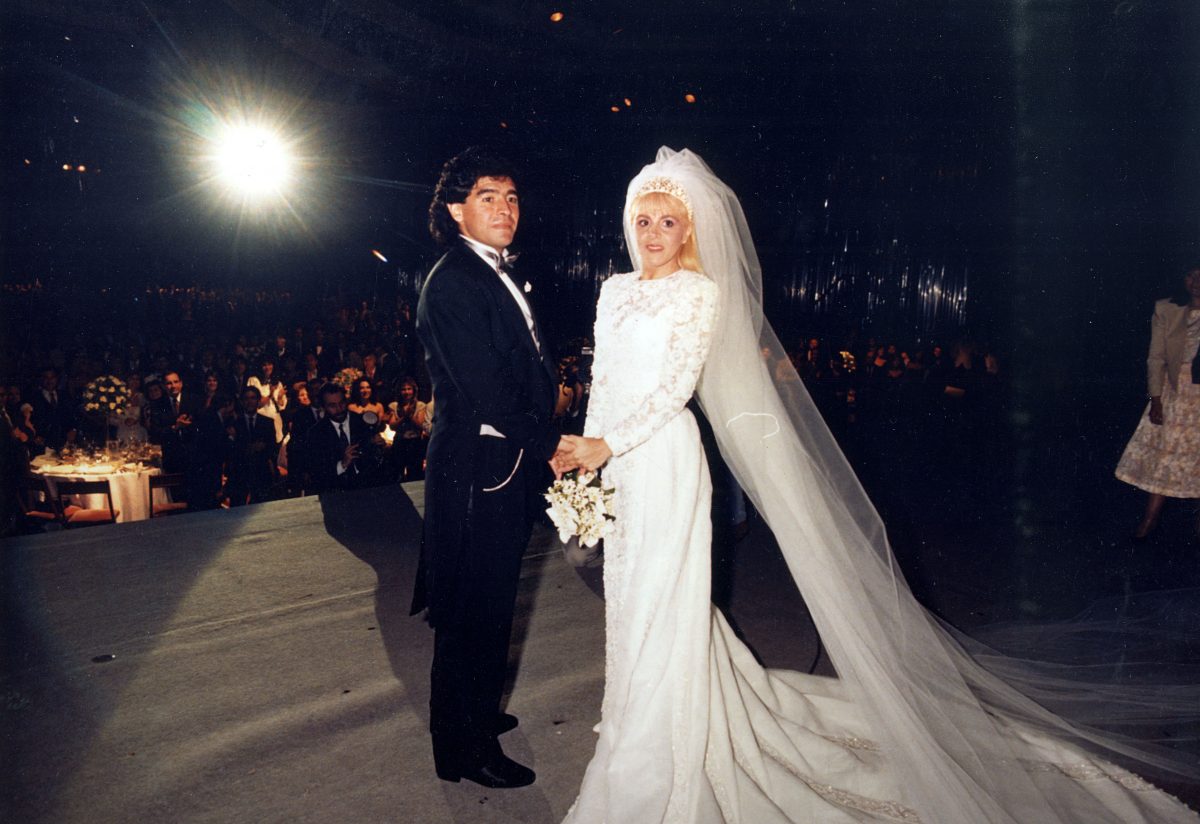

Marriage of Diego Maradona and Claudia Villafane in Buenos Aires, Argentina – 1989

Diego’s birthday bash – Seville, Spain, 1992

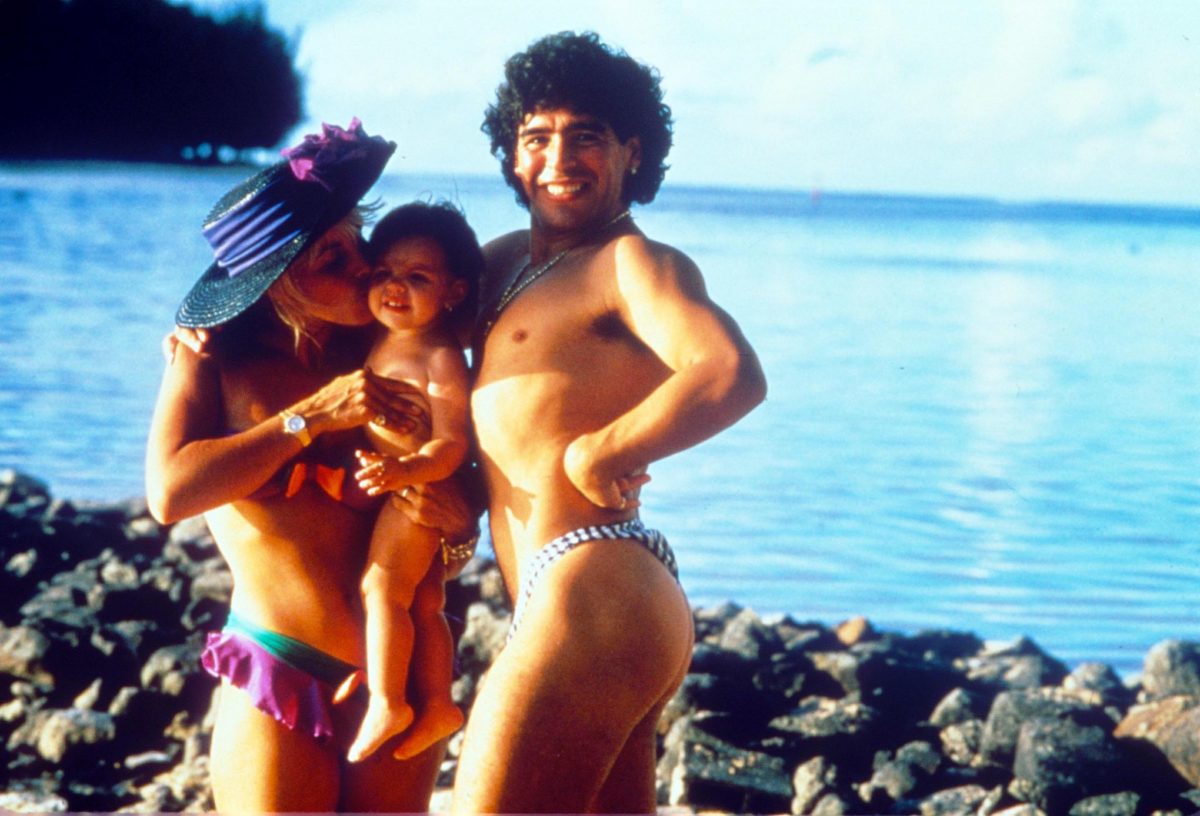

Diego with Claudia and his daughter Dalmah

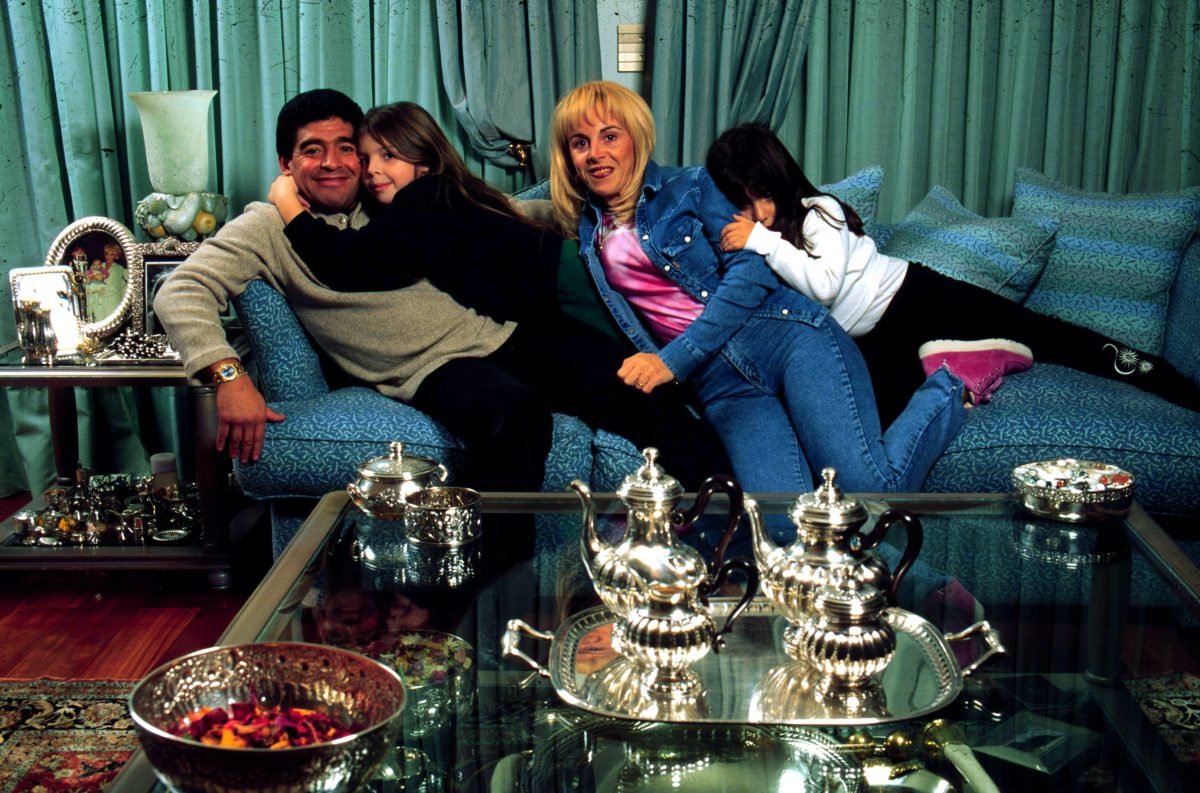

Maradona with his wife and daughters Gianina an Dalma – Bueno Aires – 1994

Diego Maradona with his parents, mother Dalma Salvadora Franco and father Diego Maradona Senior – 1980

Diego Armando Maradona in 2006

Maradona being held aloft by fans of Boca Juniors after winning the 1981 Metropolitano championship

Diego Maradona – 1980

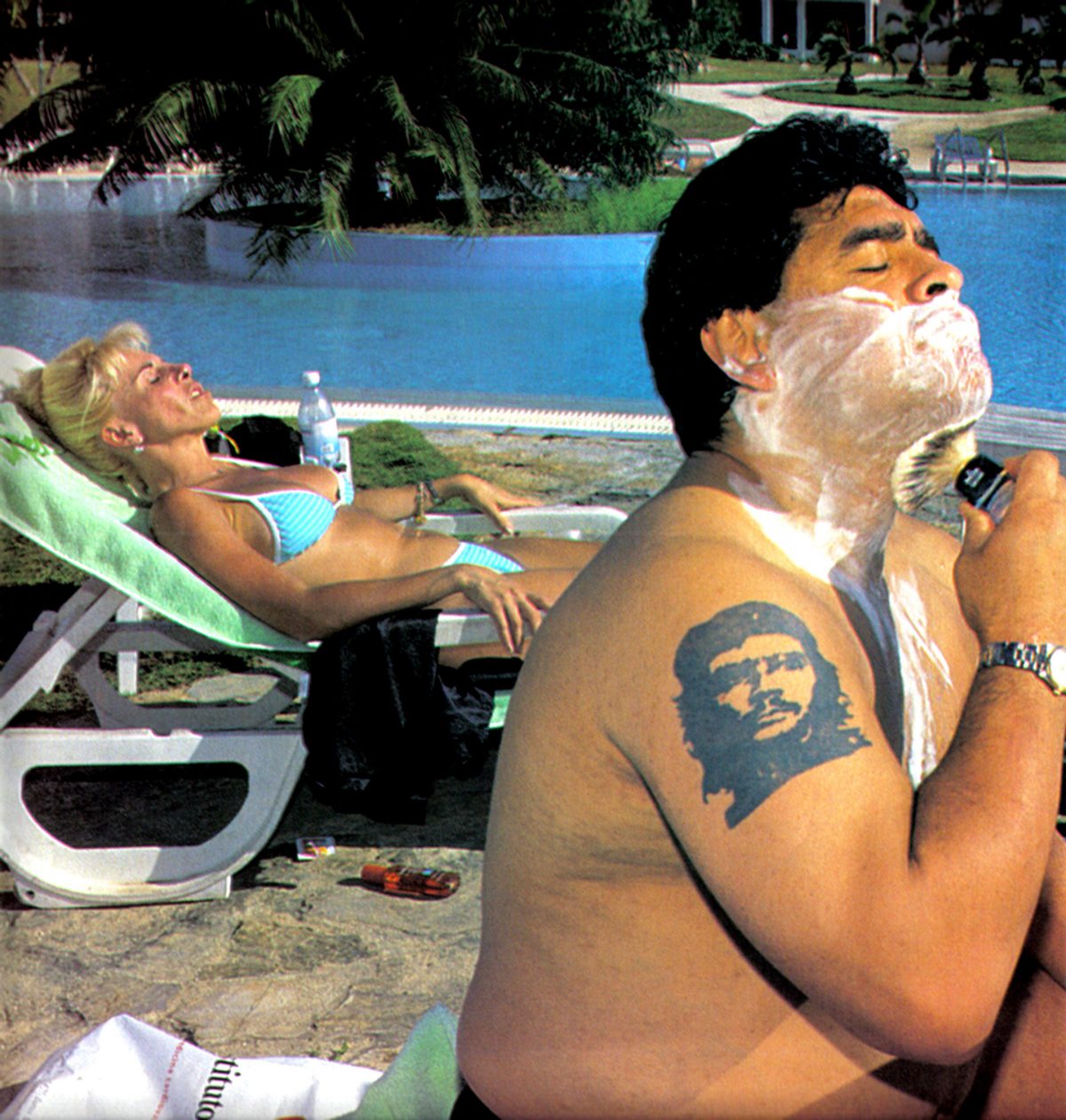

Diego Maradona smokes a Cohiba cigar as he rides a sail boat in waters off Havana April 8. Maradona was been in Cuba since January on a rehabilitation program to try to kick the cocaine habit that almost cost him his life at the beginning of the year.

Ho Visto Maradona!

https://youtu.be/A6Ccldi842E

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.