Writer, engineer, and spy Pierre Boulle drew heavily on the sciences of mathematics, physics, astronomy, and evolutionary biology for his 1963 novel La Planète des singes, published in English translations (with taxonomic confusion) as Monkey Planet in the UK and Planet of the Apes in the US. Nonetheless, when the book was received as genre fiction, the author was none too pleased. “He got very angry,” Boulle’s son-in-law Jean Loriot-Boulle recalls. “He said: ‘No, no, it’s not science fiction!’”

Boulle thought of the book as satire, a contemporary Gulliver’s Travels. Despite his intentions, Planet of the Apes would spark one of the longest running, most popular sci-fi franchises of all time, “the nucleus of a continually expanding universe,” wrote Simon Abrams in 2011, consisting of “four sequels, a remake, a TV series and several comic-book spinoffs.” Since then, we’ve seen three new films appear, the familiar latex and fake fur replaced by CGI.

The series has worked as satire as well as sci-fi, and has more than its share of humor, much of it unintentional. (Charlton Heston didn’t pound sand for our amusement when he learned it was Earth all along, but we’ll never stop laughing.) The source material grounded the story in a believable fictional universe, and The Twilight Zone’s Rod Serling stepped in for the first draft of the script and added the Cold War frisson of the shocking twist ending.

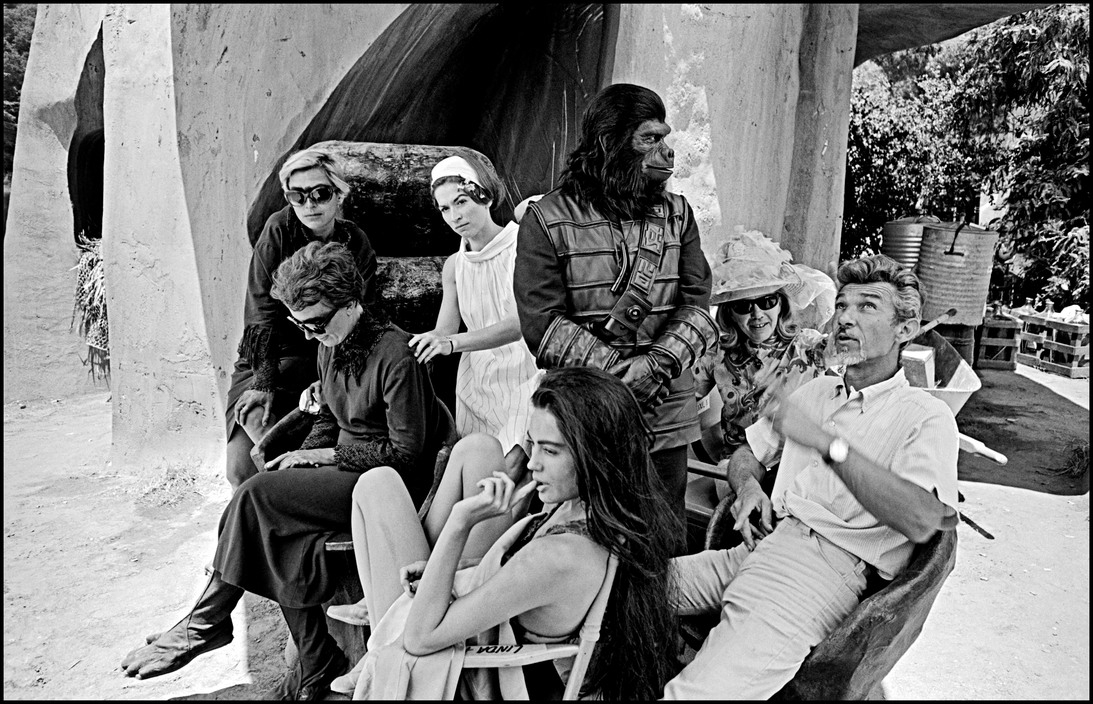

Boulle’s novel and Serling’s script described an ape society too technologically advanced to recreate on the relatively low budget 20th Century Fox decided risk on the untested 1968 film version of the book, so screenwriter Michael Wilson—who previously adapted Boulle’s Bridge Over the River Kwai—was brought on to dumb things down a bit. Nonetheless, “the original 1968 Apes production” looked like “a big studio-produced science fiction epic [featuring] elaborate make-up effects and considerable production values for the apes’ primitive, Gaudi-influenced city architecture.”

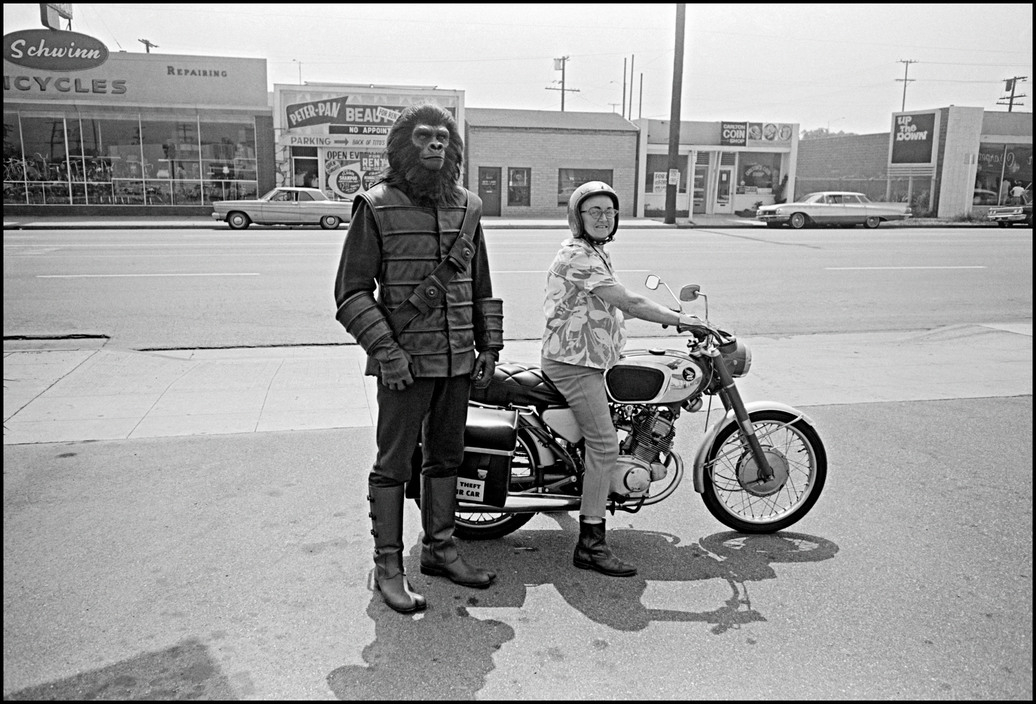

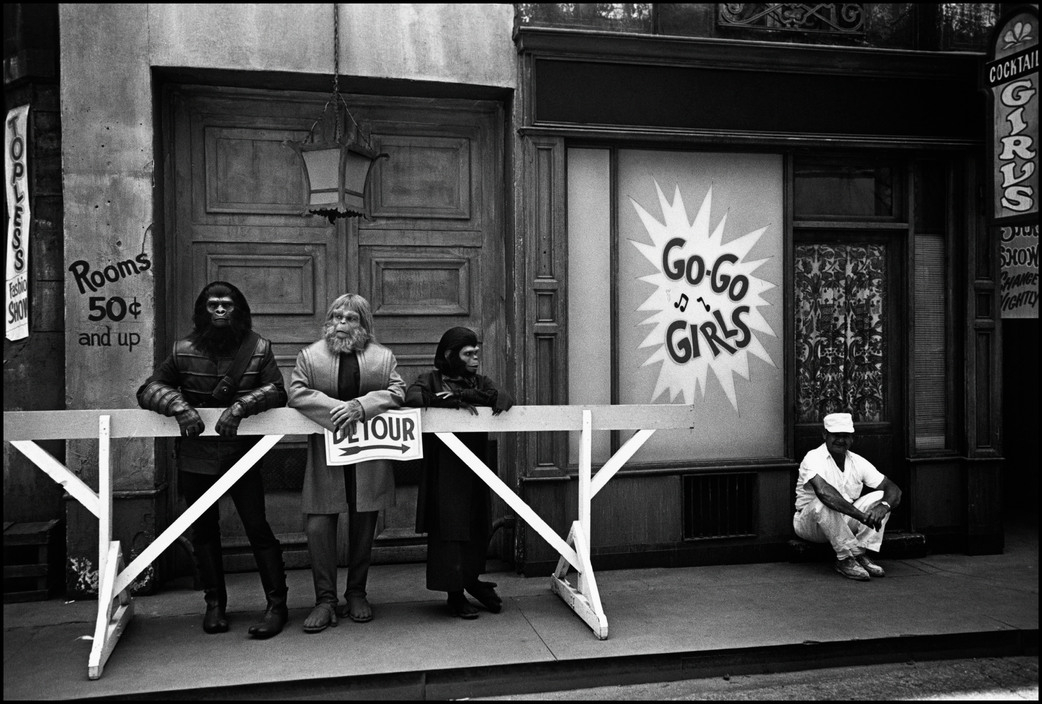

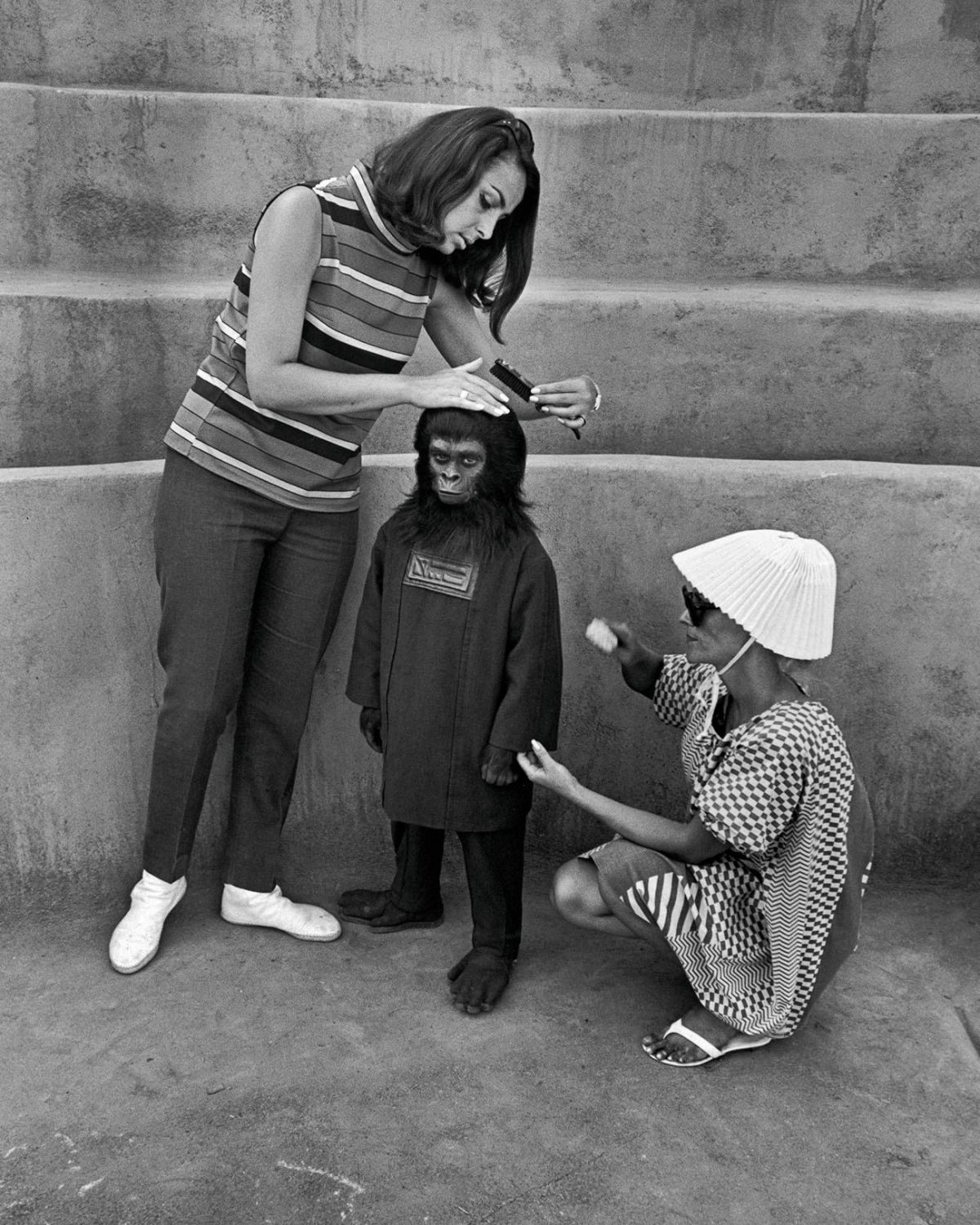

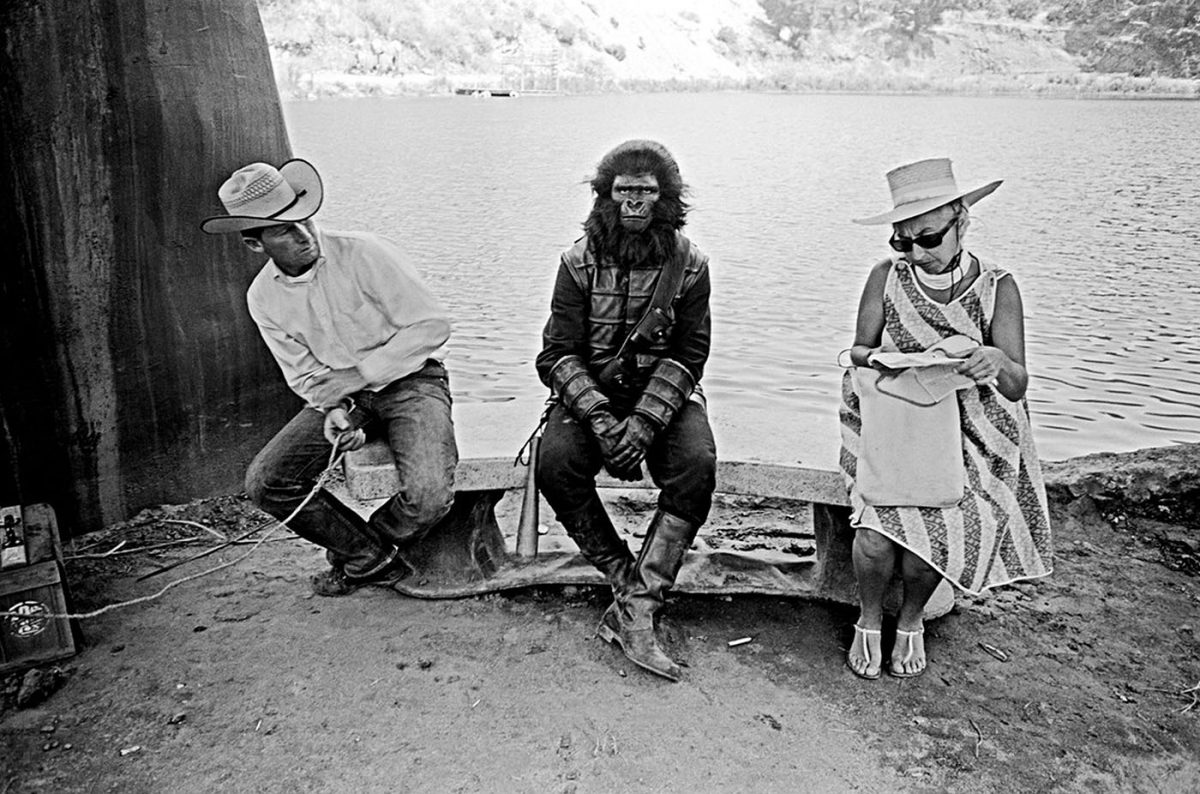

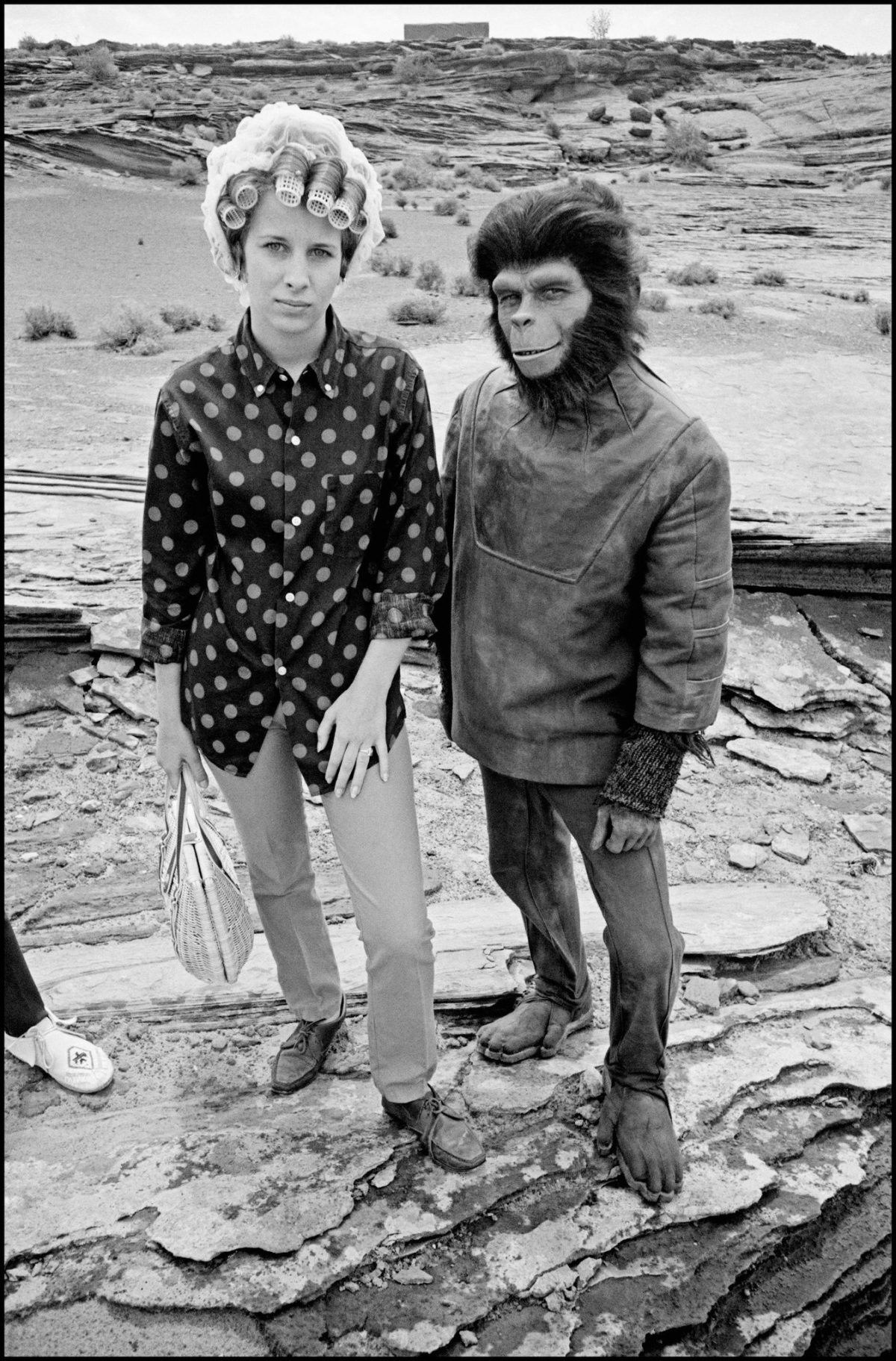

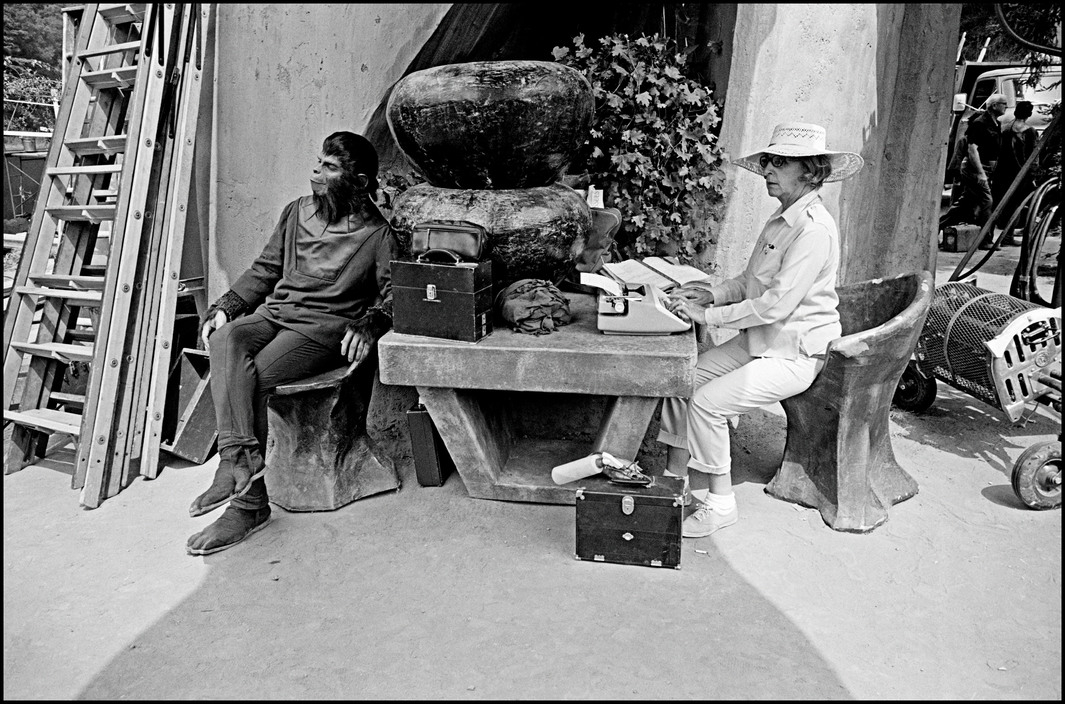

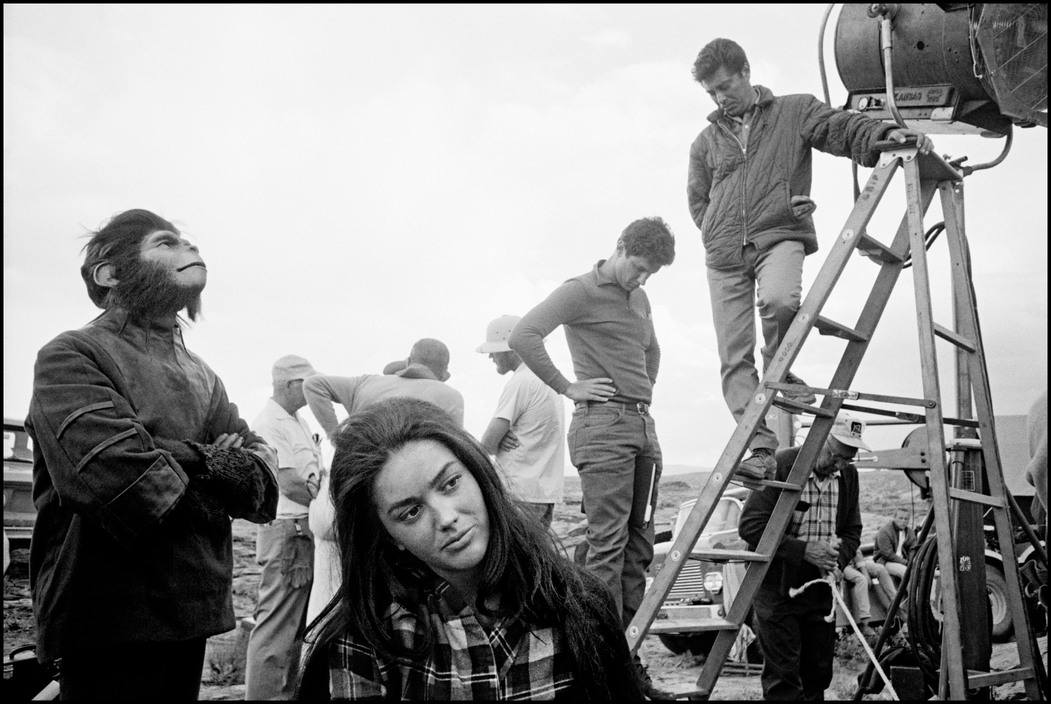

The set design, by art directors William Creber and Jack Martin Smith, relied on some sleight-of-hand to create a sense of space. Stars Heston and Linda Harrison provided sex appeal, but what really sold the franchise to audiences again and again were the incredible makeup effects by John Chambers that transformed Roddy McDowell, Kim Hunter, and Maurice Evans so completely into highly evolved chimpanzees and orangutans that audiences couldn’t recognize their famous faces at all, even when they hung out on the streets of Hollywood between takes.

As the cast and crew brought Boulle’s vision of a futuristic ape society to life, photographer Dennis Stock, who had made his name taking pictures of James Dean and famous jazz musicians, captured the action behind the scenes and in casual street scenes. All of the photos here were taken on set in Malibu and in Hollywood in 1967, a document of what no one at the time could have known would become an over fifty-year ape saga that has outlived its first creators and may outlive us all.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.