“If one wanted to crush and destroy a man entirely, to mete out to him the most terrible punishment, all one would have to do would be to make him do work that was completely and utterly devoid of usefulness and meaning.”

– Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The House of the Dead

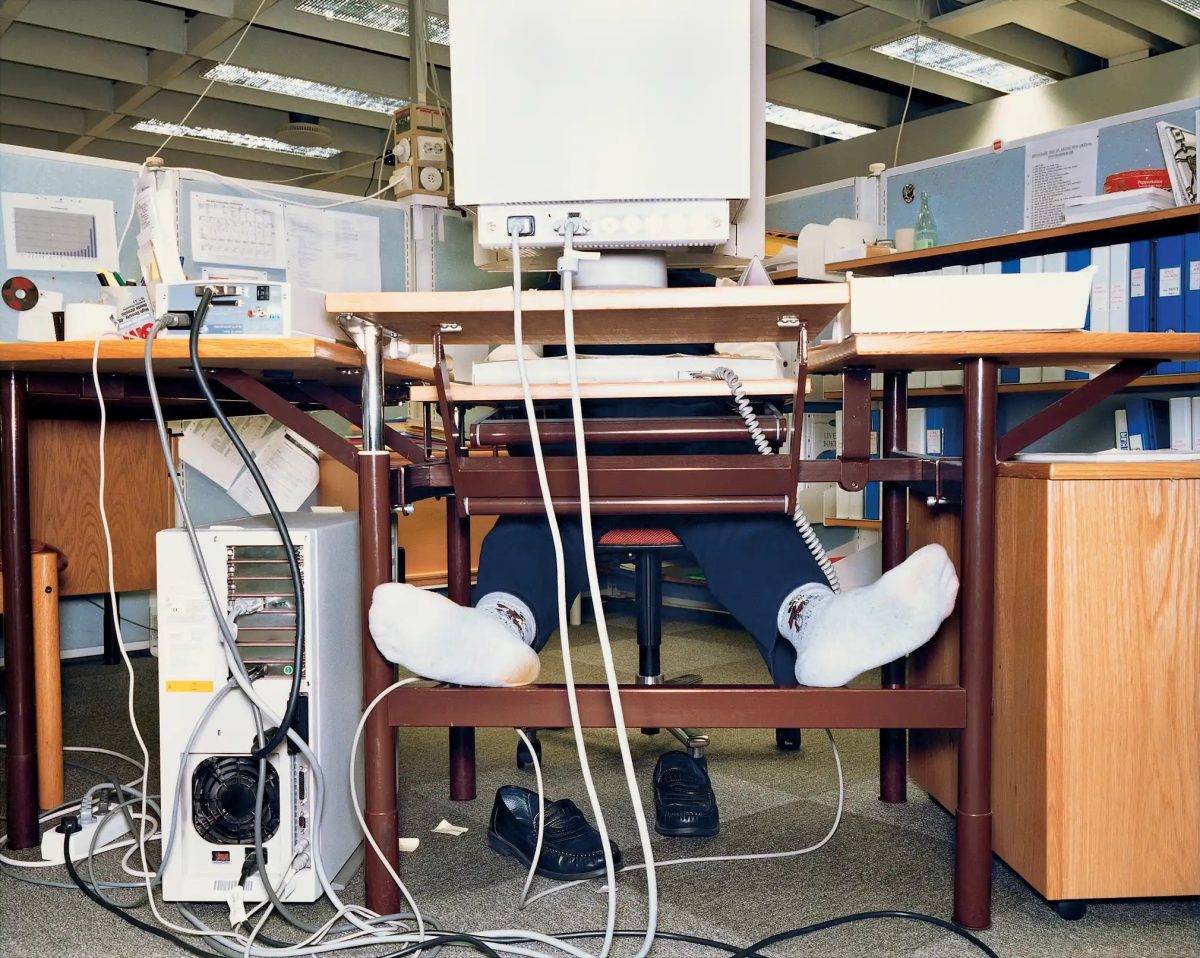

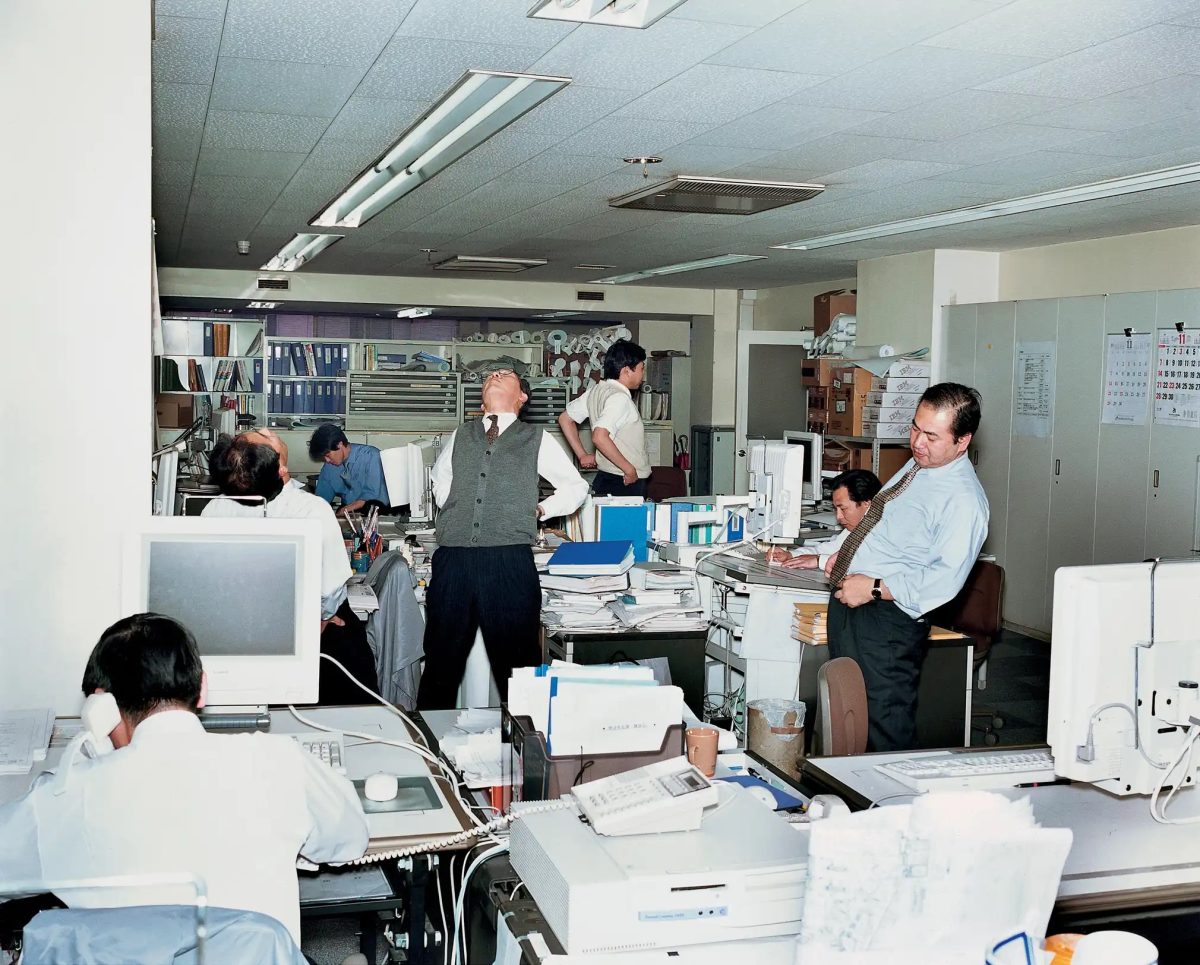

From faces of a Hong Kong toy factory in the 1970s to people of Bell Labs in the 1960s and the era when machines dwarfed the staff, the office has been a place where millions of us go to die a little day by day. Lars Tunbjörk spent the 1990s photographing “like an alien” offices in Stockholm, Tokyo and New York. For him, these are “the most common – but closed and secretive – place in the western world.”

Food industry, Tokyo, 1999

In his book Bullshit Jobs, David Graeber sums up the banality of office life:

“While the winds of change may have transformed the grey dividers into WeWork couches or the clunky dial-up PC into a sleek, pocketable touchscreen tablet, Tunbjörk’s images capture a contingent sense of ennui and isolation still prescient in an era of bullshit jobs, quiet quitting and working from home.”

The office is the place of hierarchical misery. It’s where the passionless and emotionally dislocated seek to justify their existence through the accumulation of a security pass, a catered sandwich delivered to their ‘hot desk’, and if they try very hard a job title they can add to their emails that pulls rank on the mortals they patronise in asinine meetings that ultimately encloses them firmly in the trap of their own making.

“In the year 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that, by century’s end, technology would have advanced sufficiently that countries such as Great Britain or the United States would have achieved a 15-hour work week. There’s every reason to believe he was right. In technological terms, we are quite capable of this. Yet it didn’t happen.

Instead, technology has been marshalled to figure out ways to make us all work more. In order to achieve this, jobs have had to be created that are, effectively, pointless.

Huge swathes of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed. The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul. Yet virtually no one talks about it’

Why did Keynes’ promised utopia never materialise? The standard line today is that he didn’t factor in the massive increase in consumerism. Given the choice between fewer hours and more toys and pleasures, we’ve collectively chosen the latter. This presents a nice morality tale, but even a moment’s reflection shows it can’t really be true’

Yes, we have witnessed the creation of an endless variety of new jobs and industries since the 1920s, but very few have anything to do with the production and distribution of sushi, iPhones, or fancy sneakers”

– David Graeber

Lars Tunbjörk was born in the Swedish town of Borås, a place which was a big influence throughout his career

Tunbjörk was also influenced by Swedish photographer Christer Strömholm and American photographer William Eggleston

The quotes in this piece are taken from David Graeber’s essay Bullshit Jobs, originally published in 2015 for Strike! Magazine

Construction company, Tokyo, 1999

Civic administration, Tokyo, 1996

Stockbroker, Tokyo, 1999

LA

Civic administration, Tokyo, 1996

Lars Tunbjörk’s Office/LA Office is available at Loose Joints. All photographs by Lars Tunbjörk

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.