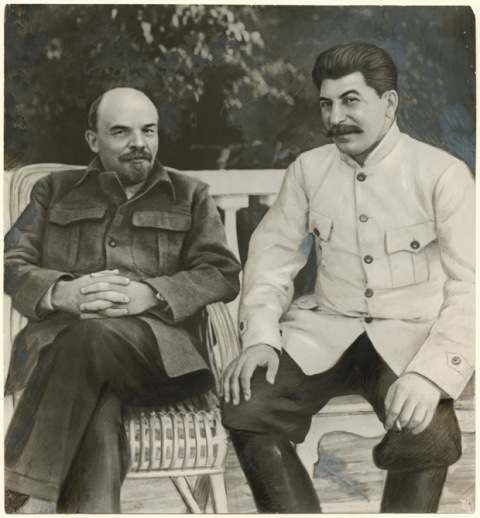

“The painter constructs, the photographer discloses” – Susan Sontag

Man on Rooftop with Eleven Men in Formation on His Shoulders (Unidentified American artist, ca. 1930)

Do we believe what we see in photography and video? We should view images with one eye on the creator: the propagandist who places the child’s toy atop the rubble of war, or a skull in an arid plain; the miracle-cure-weight-loss-selling hustler who shoots the unhappy fat slumped from the front and the joyful slimmed inhaling from the side; the editor behind the highlights packages on the evening news picking the running order and where to crop the pictures?

Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Mia Fineman writes (via):

Over the past twenty years, photography has undergone a dramatic transformation. Mechanical cameras and silver-based film have been replaced by electronic image sensors and microchips; instead of shuffling through piles of glossy prints, we stare at the glowing screens of laptops, tablets, and mobile phones; negative enlargers and chemical darkrooms have given way to personal computers and image-processing software. Digital cameras and applications such as Photoshop have create, look at, and think about photographs. Among the most profound cultural effects of these new technologies has been a heightened awareness of the malleability of the photographic image and a corresponding loss of faith in photography as an accurate, trustworthy means of representing the visual world. As viewers, we have become increasingly savvy, even habitually skeptical, about photography’s claims to truth.

It’s easy to fake a photo. But before the internet the fakers had to work hard to be creative:

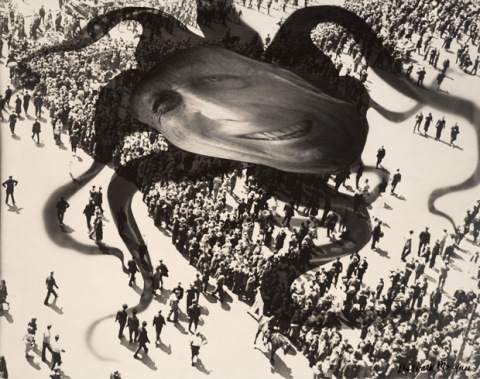

Sueño No. 1: Articulos eléctricos para el hogar / Dream No. 1: Electrical Appliances for the Home (Grete Stern, 1948)

1917: 15-year-old Elsie ‘Iris’ Wright (1901-1988) and her 10-year-old cousin Frances ‘Alice’ Griffiths found fairies at Cottingley, near Bradford.

Inevitably, we see a photograph based on our beliefs – what we believe about the photographer’s intentions, our political beliefs, and the context in which the photograph appears. Think of all the ways the meaning of a photograph can change. The photographer takes a picture; a journalist writes a caption; the picture appears in an article; it is cropped or appears with other images (which skew the meaning); or it appears in a publication with known (or suspected) political sympathies; often photographs that seemingly express a point of view that we don’t like are seen as propaganda. And photographs that seemingly express a point of view that we do like are seen as journalism. People rarely find fault with photographs that accord with their own beliefs.

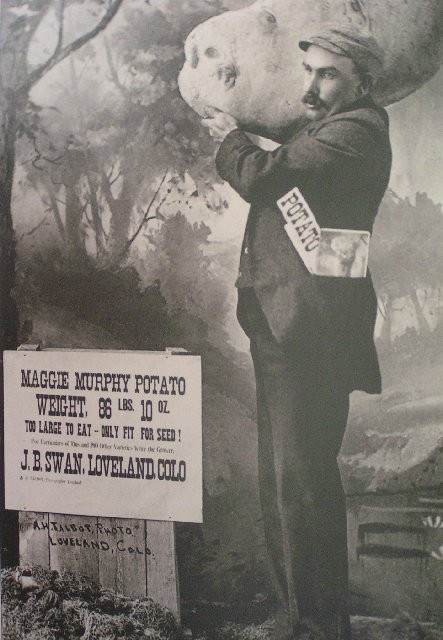

The Museum of Hoxes explains the above photo:

W.L. Thorndyke, editor of the Loveland Reporter, came up with an idea to help Swan promote his spuds at an 1894 street fair. Thorndyke’s idea was to create a hoax photograph of Swan showing off a truly massive potato — one as large as a boulder. He suggested Swan could pass around copies of the photo as a tongue-in-cheek advertisement.

To make the photo, Swan and Thorndyke enlisted the services of photographer Adam H. Talbot. Talbot took a photo of a potato and enlarged it to mammoth size. He then cut out a wooden board the size and shape of this enlarged image and he attached the photograph to the board. Finally, he posed Swan holding this giant faux-potato on his shoulder.

A meme was born (see more here).

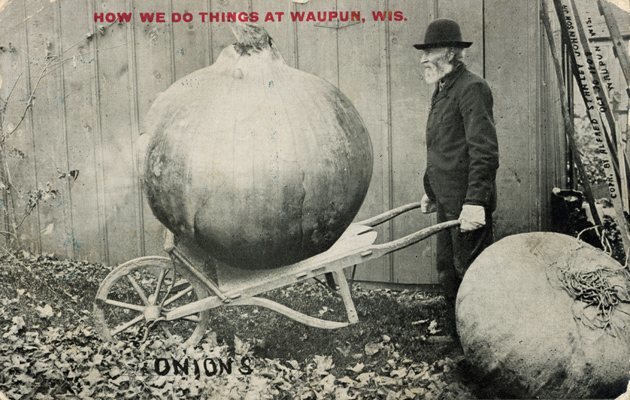

Postcard features agricultural trick photography (by Martin Photography Company of Oxford, Kansas) of a farmer as he saws an enormous ear of corn, circa 1910 . (Photo by Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images)

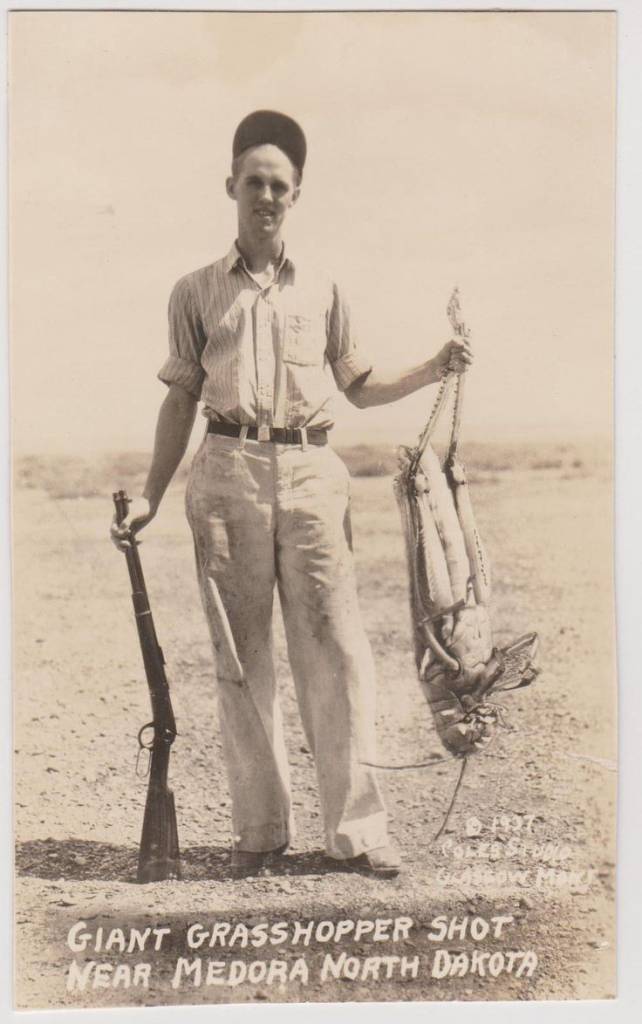

Big crops mean big pests:

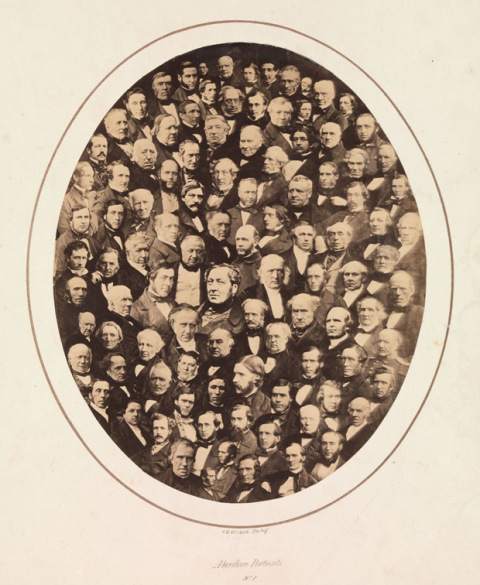

Founded in 1854, the London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company was a major publisher of stereographs-cards with two nearly identical photographs mounted side by side that can be viewed through a binocular device to create an illusion of depth. The firm’s output was colossal; their 1858 catalogue listed more than one hundred thousand views. While the majority of these were landscapes or architectural views, there was also a thriving market for staged historical, sentimental, or comic tableaux, which were often hand-colored to enhance their dramatic impact. Among the most popular themes were courtship, marriage, unrequited love, bereavement, children sleeping or praying, fairy tales, fortune telling, and supernatural scenes involving ghosts or spirits.

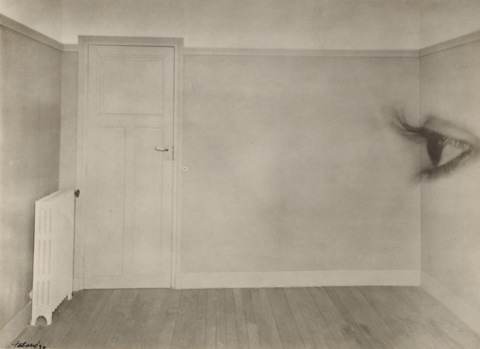

A photograph of Will Thomas, taken by William Hope (1863-1933). A man’s face appears in a haze of drapery on the right of the photograph. Thomas, a medium from Wales, did not recognise the superimposed image. Thomas has signed the bottom of the photograph, ‘Sincerely Yours Will Thomas’ – perhaps this indicates a friendship with Hope. Hope’s spirit album photographs use double and even triple exposure techniques to render the appearance of ghostly apparitions around the sitter. Hope founded the spiritualist society known as the Crewe Circle and his work was popular after World War One when many bereaved people were desperate to find evidence of loved ones living beyond the grave. Although his deception was publicly exposed in 1922, he continued to practice. More here.

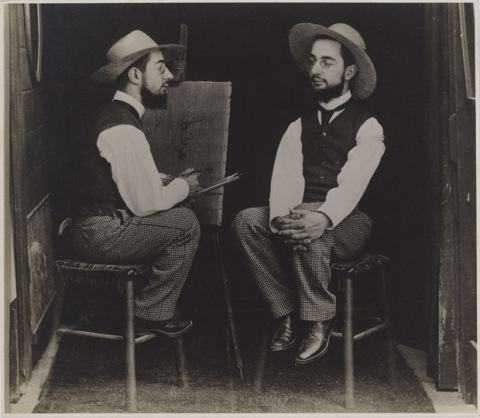

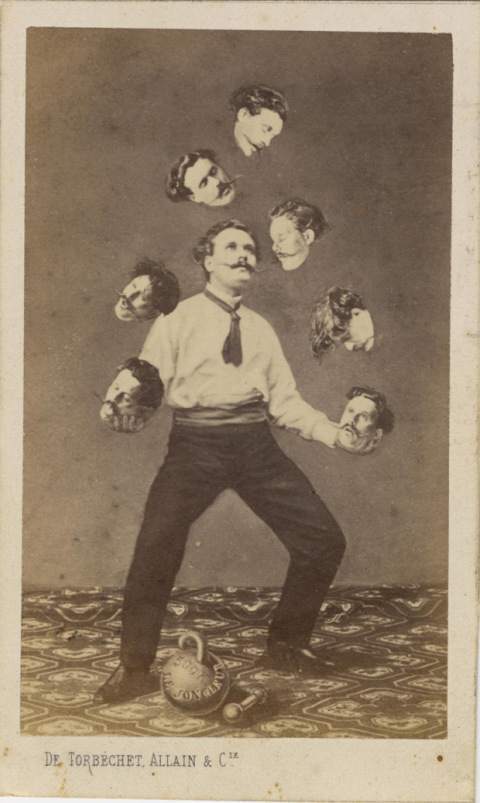

Man Juggling His Own Head (Unidentified French artist, Published by Allain de Torbéchet et Cie. ca. 1880)

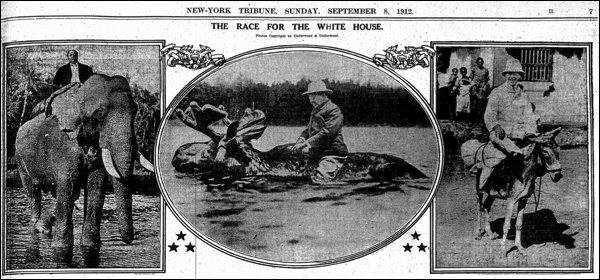

Two months before the election, on Sep 8, 1912, the New York Tribune ran a set of humorous pictures under the headline “The Race For The White House,” showing the three main presidential candidates astride the animals associated with their parties.

William Howard Taft was shown riding an elephant (for the Republican party). Woodrow Wilson sat on a donkey (for the Democratic party). And Roosevelt rode a moose (for the Bull Moose party).

All three images were fake. They had been created by the photographic firm Underwood and Underwood.

April Fool’s Day edition of a German news magazine, the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung. Man flies by the power of his breath.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.