Jim Grover’s photographs of the Windrush generation at home in south London are a joy. His project began in June 2017 in Grover’s local church. A parishioner invited him to see the clubs where he played “bones”. “It was a revelation to me,” says Grover. “I had no idea that Caribbean migrants met three times a week for dominoes in Clapham, where I’ve lived for 30 years.” Jim went to more dominoes clubs in Clapham, Croydon and Wandsworth. He was soon welcomed into homes, community centres, places of worship and funerals.

Three nights a week Caribbean men play dominoes in the West Indian Association of Service Personnel (‘WASP’) club in Clapham, South London. The dominoes team, which plays against other local West Indian dominoes clubs, is called WASPS.

“So my eleven-month journey began. It was to take me to many homes, clubs, community groups, churches and cemeteries in and around Clapham. At first it wasn’t easy. I was a stranger in their midst (with a camera and sometimes a voice recorder!) and people were, understandably, a little uncertain of me and my intentions. But as we got to know each other this warm-hearted community opened up their lives and their homes to me, and enabled me to tell their story.

“Knowing that I wanted to capture the totality of the particular ways this generation live their lives gave me a structure for my endeavours over the ensuing months, and drove my constant pleas for advice, ideas, help, contacts and, that most precious thing for a photographer, ‘access’. For example, I knew that I had to capture a ‘Nine Night’; I was determined to find an intact example of the legendary ‘Jamaican Front Room’.”

– Jim Grover

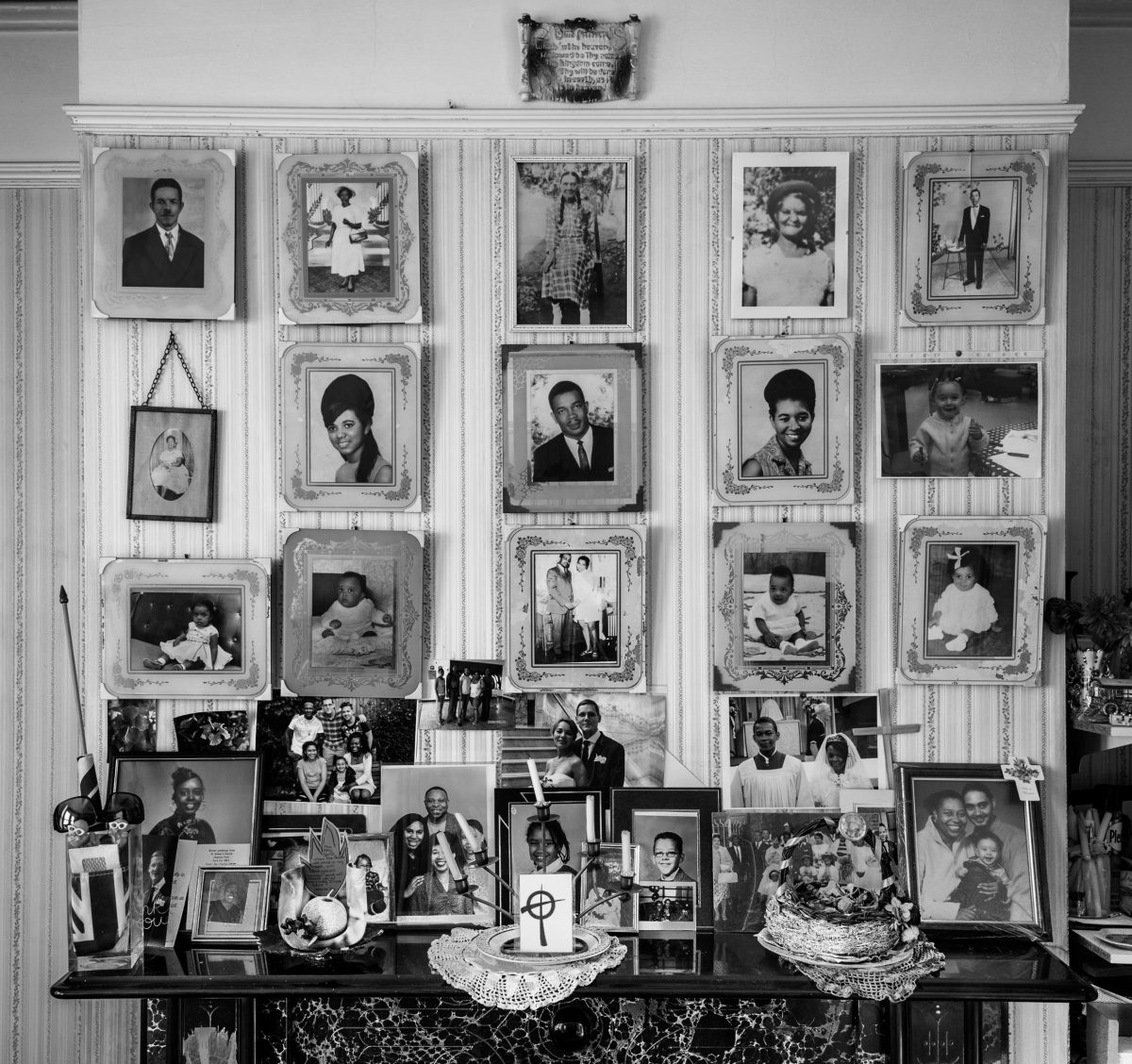

First generation Caribbean homes (irrespective of how crowded they were with owners and tenants) would typically have a (very!) special room called ‘The Front Room’, which was kept locked and only used on special occasions. It would be filled with glass cabinets; ornaments; artificial flowers; family portraits; pennants; a gramophone (such as ‘The Blue Spot’). They have now largely disappeared.

Jim Gover’s work is timed to coincide with the 70th anniversary of the arrival of Empire Windrush at Tilbury docks in June 22 1948. The ship brought 492 young hopefuls from the Caribbean, mostly Jamaican men, to help rebuild Britain in the aftermath of the war. Hermine Grocia was typical of many who came to “Missus Queen’s” country determined to work.

This was a momentous event in the evolution of Britain’s cultural life: the arrival of those first passengers and ensuing steady flow of migrants from the Caribbean over the next 14 years, often referred to as the ‘Windrush generation’, was a major step in the creation of a multi-cultural Britain.

Many of the Windrush generation live in Brixton and Clapham in south London as some of the very first ‘Windrushers’ were accommodated in the underground war shelter at Clapham South and sought their first jobs at the Brixton labour exchange.

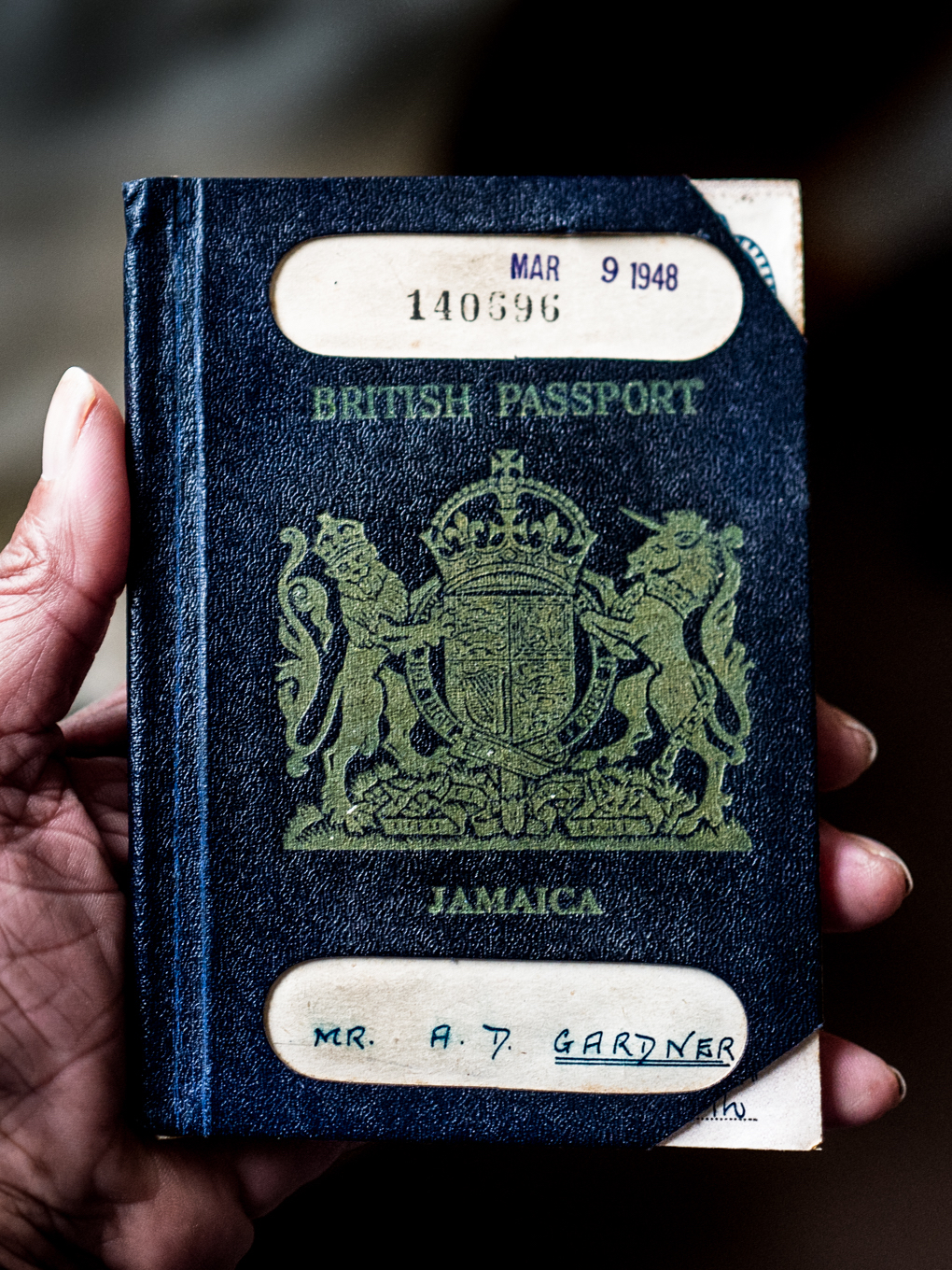

Through Jim, we meet Alford Gardner, 92, at home in Leeds. “I knew I had to track down at least one surviving ‘Windrusher’ if I were to do justice to this story,” says Jim. Alford Gardner served in the RAF during the war as a motor mechanic. He paid the standard £28 to cross the Atlantic on the Windrush. In Leeds he found work with commercial engineers. “I’ve lived a brilliant life here,” says Alford. “It was supposed to be tough, but I never really had tough times.”

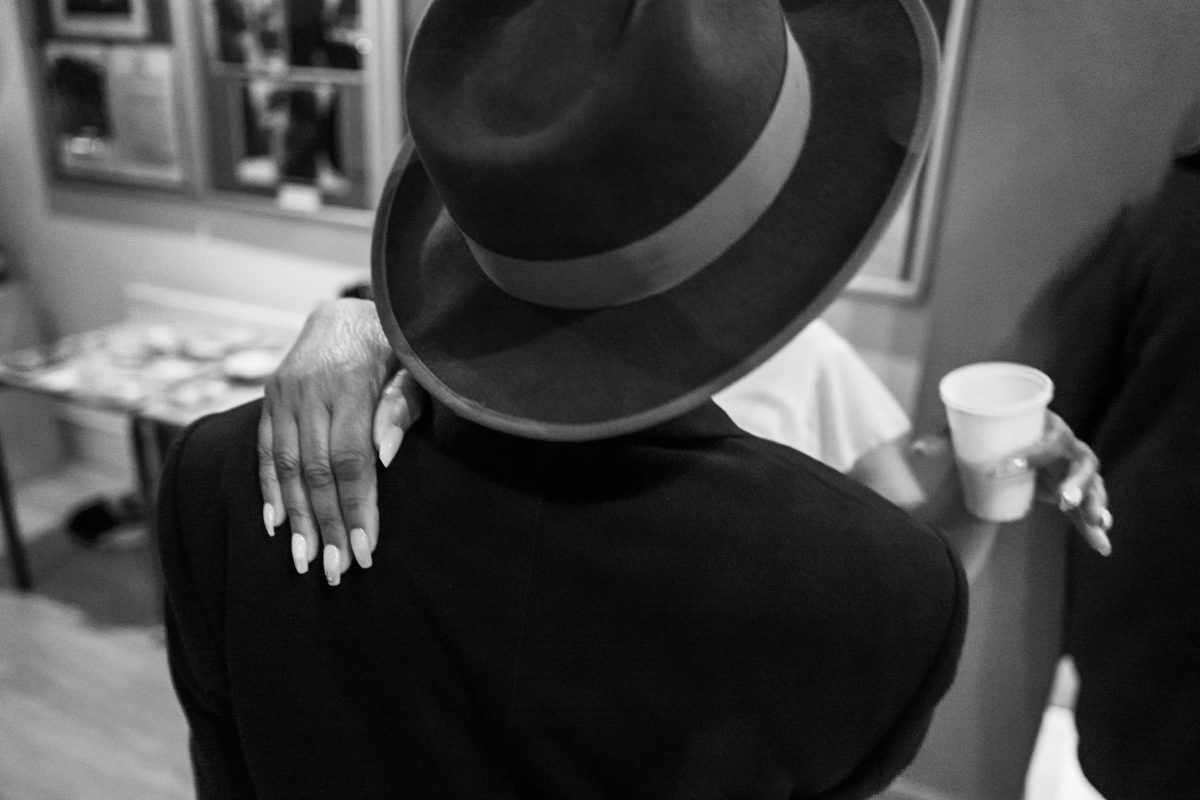

Bockie and Lorraine dance together at the Christmas get-together in the West Indian Association of Service Personnel club in Clapham Manor Street, London, December 2017. Bockie loves a dance and a party. He was born in Jamaica as one of 10 children and arrived here in 1968, at the age of 16, to join his parents

In migrating here, the Windrush citizens believed they were exercising their birthright. “UK – Right of Abode” was stamped in their Commonwealth-issue passports. Teachers, lawyers, writers, artists and field labourers came in response to a recruitment drive and because they hoped for a better life. Not all of the Windrushers had intended to remain “in foreign”, but gradually it dawned on them that the dream of return was just that: they were here to stay.

Diane Bailey pours rum into her mother’s grave, ‘her final tot’, as part of a traditional Jamaican funeral.

“At the Jamaican funeral I was literally standing at the grave’s edge. It required a good deal of trust… In order to capture a dominoes match and its after-party, I sometimes had my camera out for long stretches – seven or eight hours. At other times, I just sat and listened to stories and watched life unfold in front of me.”

– Jim Grover

Monica, who arrived in south London from Jamaica in 1964, has made this same journey to her local church, St James’s in Clapham, some 5000 times over the last 47 years. Monica Blair attends Sunday service at St James church in Clapham, January, 2018. Monica arrived from Jamaica in 1964, aged 21, to marry Soney. ‘When I wake up, the first thing I do is say my prayers… My faith is important for me. If I don’t go to church, for example if I am ill, then I feel down, I worry about it’

Monica (above) arrived from Jamaica in 1964, aged 21, to marry Soney and worked as a cleaner at St Thomas’ hospital near Westminster, before becoming a seamstress. With her deep religious faith, Monica attends the same Anglican church in Clapham as Grover. In his photographs, she ministers communion wine and pores over a well-thumbed Bible, a gift to her as a teenager in Jamaica.

First generation immigrants continue to wear their hats, of all sorts and both indoors and outdoors, at their distinctive jaunty angle!

“The more I immersed myself in this project, the more I realised that I was capturing living history. As this generation passes away, and the successive generations pursue their own lives here, some of these traditions will inevitably weaken. It felt imperative to document this way of life and to record these stories before it becomes too late.”

– Jim Grover

Remembrance Sunday 2017 in Windrush Square, Brixton, south London. The new war memorial was unveiled in June 2017 to honour the contribution of service personnel of Caribbean and African origin in both world wars. Some 16,000 West Indians served in WW2 with 236 killed or reported missing. Their contribution is often overlooked.

Preparing the ‘rice and peas’ for a ‘nine nights’ celebration in a Jamaican home in Clapham, south London. According to Jamaican tradition it takes nine nights before the spirit of the deceased is finally at rest. The ‘nine nights’ is a time for family and friends to get together to respect and honour the recently departed, ahead of the funeral; it is typically held 9 days after death (and hence everyone knows when to come).

ALFORD GARDNER: MARCH 2018

Alford Gardner, currently 92, is one of the tiny number (estimated at no more than 10) of survivors from ‘Empire Windrush’ which arrived in Tilbury on June 22nd 1948.

Three nights a week Caribbean men play dominoes in the West Indian Association of Service Personnel (‘WASP’) club in Clapham, South London. The dominoes team, which plays against other local West Indian dominoes clubs, is called WASPS.

First generation Caribbean homes (irrespective of how crowded they were with owners and tenants) would typically have a (very!) special room called ‘The Front Room’, which was kept locked and only used on special occasions. It would be filled with glass cabinets; ornaments; artificial flowers; family portraits; a drinks trolley or bar; pennants; a gramophone (such as ‘The Blue Spot’). They have now largely disappeared.

Monica, who arrived in south London from Jamaica in 1964, being ‘ashed’ in her church of St James’s in Clapham in February 2018. Monica has attended her church some 5000 times over the last 47 years. First generation Caribbean immigrant women are typically very strong in their faith.

COMMUNITY: TAI CHI AT ‘STOCKWELL GOOD NEIGHBOURS’

‘Stockwell Good Neighbours’ was founded in 1974 to provide a community centre for first generation West Indian immigrants. It still meets weekly. Its 60 members are almost all West Indian women aged between 60 and 103. Tai Chi features each week.

Members of the Stockwell Good Neighbours play bingo at their regular Monday meeting in the Oval theatre bar, February, 2018. Stockwell Good Neighbours is a charity founded in 1974 for the West Indian community by the local church of St Andrew’s in Landor Road. Forty four years later, it still meets every Monday. A weekly £4 gets you exercise classes, lunch, a raffle, bingo, and a chance to catch up with your friends. The 60 members, most of whom are women, are aged between 60 (an entry requirement) and 103

Windrush: Portrait of a Generation is at gallery@Oxo, Oxo Tower Wharf, London SE1, 23 May-10 June. Ian Thomson’s The Dead Yard: A Story of Modern Jamaica, is published by Faber

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.