Lord Boothby, Ronnie Kray and Leslie Holt

To his face, the writer, campaigner and broadcaster Sir Ludovic Kennedy once called Baron Boothby of Buchan and Rattray Head, his mother’s cousin, ‘a shit of the highest order’. Boothby’s response was to chortle, rub his hands and say: ‘Well a bit. Not entirely.’ For most of his life, his undeniable charm, along with close friends in very high places, kept any scurrilous rumours, malicious gossip and untoward behaviour of Boothby, much of it true, away from the front pages of Fleet Street. But by 1964, however, especially after the Profumo Affair the previous year, Britain’s newspaper industry had developed more than a little taste for Establishment blood.

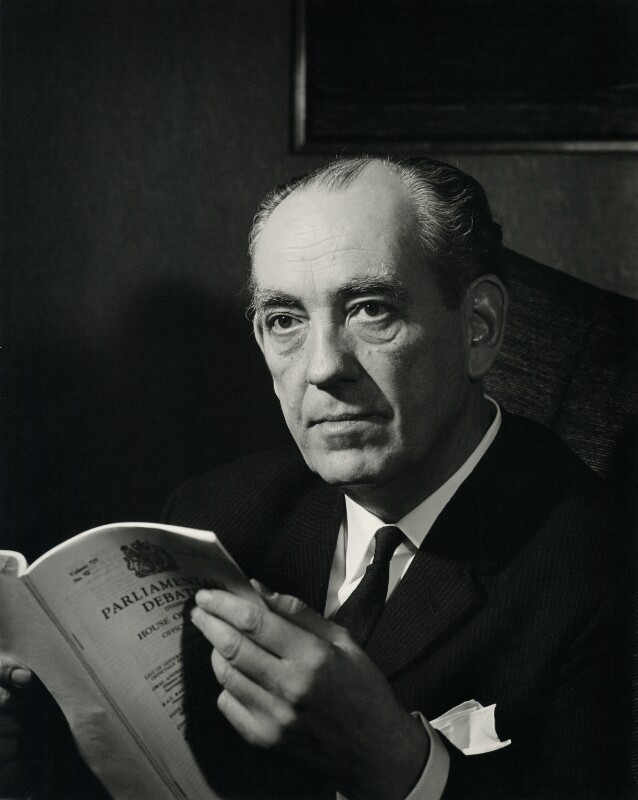

In the early 1960s, Boothby, known throughout his life as Bob, was one of the country’s more famous politicians, albeit now in the House of Lords. Although he had been in Parliament for over forty years, it was broadcasting, however, rather than high office that had made him truly a household name. During the 1950s his eloquence and avuncular manner meant that Boothby appeared on many current affairs programmes on television and radio and in March 1964 his fame was underlined when he appeared on the BBC’s This Is Your Life with Eamonn Andrews. Just a few months later, the carefully constructed wall of discretion built around his colourful private life began to break down…

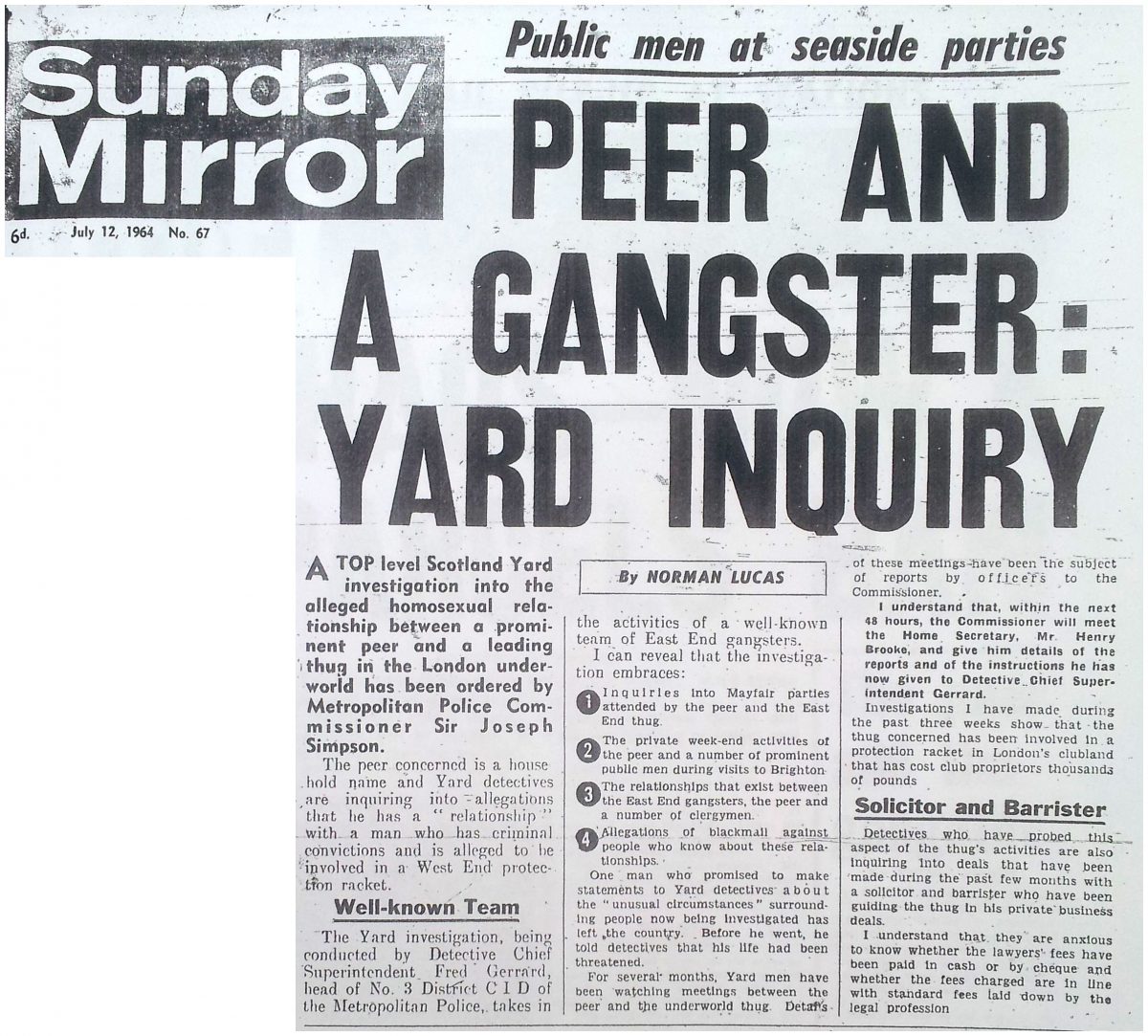

On Saturday 11 July 1964, most of the newspaper offices were finding it rather a dull day for news. Even the weather was dull – cloudy and mild with the occasional drizzle. Only the Sunday Mirror’s front page had any prominent sense of excitement, with a headline that proclaimed: ‘Peer and a Gangster: Yard Probe – Public Men at Seaside Parties’. The popular Sunday newspaper claimed that the police were investigating ‘a homosexual relationship between a prominent peer and a leading thug in the London underworld’. The peer was a ‘household name’ and the inquiries embraced Mayfair parties attended by the peer and the notorious gangster. A few days later, the Daily Mirror announced that it had a photograph – ‘the picture that we must not print’ – which showed ‘a well-known member of the House of Lords seated on a sofa with a gangster who leads the biggest protection racket London has ever known’.

Sunday Mirror, 12th July 1964

On 28 July, the West German magazine Stern, with a circulation of 1.8 million, published an article headlined ‘Lord Bobby in a fix’. It reported that the Sunday Mirror possessed something which it dare not print – ‘a picture of a peer sitting on a sofa with a known degenerately talented criminal’. The magazine not only went on to name the peer as Lord Boothby, but also stated that ‘London newspapers give us to understand’ that the peer’s position in society helps to provide the gangsters with customers who have money to pay for gambling debts and ‘more unorthodox pleasures’.

Along with Lord Boothby, the photograph featured Ronnie Kray, one of the infamous East End gangster twins (who actually at the time, outside of their East End manor anyway, were hardly known at all) and Ronnie’s friend, a gay, good-looking young cat burglar called Leslie Holt. All three were perched on a sofa in Boothby’s flat, which had the prestigious address, even for salubrious Belgravia, of No. 1 Eaton Square. When the story broke, Boothby was holidaying in France, taking the waters at the spa town of Vittel, and would later write that he was initially baffled as to the peer’s identity (extremely unlikely, as he was holidaying with Sir Colin Coote, the editor of the Telegraph and the man who could be said to have started the Profumo affair when he introduced Stephen Ward to the Soviet attaché Eugene Ivanov). When Boothby arrived back home to a London ‘seething with rumours’, he called his close friend, the former Labour Party chairman and journalist Tom Driberg, who said, according to Boothby, ‘I’m sorry Bob, it’s you…’

Boothby and Churchill budget day 1927

Lord Boothby’s house at no. 1 Eaton Square.

Robert John Graham Boothby, an only child, had been born to an Edinburgh banker two months into the twentieth century. He was educated at Eton and Oxford University and before the end of the First World War, although too young to see active service, was commissioned into the Brigade of Guards. At the age of twenty-four he became the Unionist MP for the relatively marginal Aberdeen and Kincardine East constituency, and then went on to be returned with large majorities at eight general elections.

He had been a friend and supporter of Sir Winston Churchill at a time when his allies were in relatively short supply, and in the late 1920s Boothby became Churchill’s parliamentary private secretary. Boothby, however, was too impulsive and outspoken to be a good party politician, and opinions between the two men often clashed. The Scottish MP was always uncommonly consistent with his anti-appeasement views (in Germany he was once greeted by Hitler’s secretary with a ‘Heil Hitler’, to which Boothby’s admirable response was ‘Heil Boothby’) and he was also among only thirty-three Conservatives, including Churchill, who voted against the government over Munich – the settlement in September 1938 that allowed Nazi Germany to annex the German- speaking parts of Czechoslovakia along the country’s borders, for which a new territorial designation, ‘Sudetenland’, was coined.

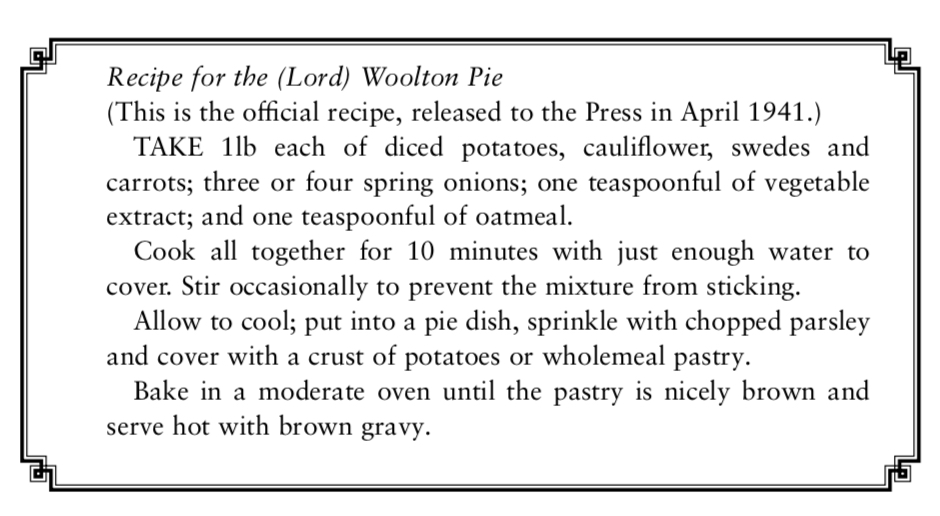

After Churchill had replaced Neville Chamberlain as Prime Minister in May 1940, he made Boothby Parliamentary Secretary at the Ministry of Food, where he worked under the minister, Lord Woolton. The Woolton Pie, was named after him a pastry dish of vegetables created at the Savoy Hotel by the Maitre Chef de Cuisine, Francis Latry, at a dinner in honour of the new American Ambassador, John Winant. ‘What is this?’ Churchill asked the waiter as the vegetarian dish was put in front of him. ‘Woolton pie, sir,’ he replied. ‘It is what?’ exclaimed the great man. ‘Woolton pie, sir,’ he repeated, to which Churchill responded, ‘Bring me some beef!’

Lord Woolton

Woolton and Boothby initially got on well and felt that they made a good team. In July 1940, the newspapers reported how Boothby, after an initial idea by Woolton, had come up with a popular national scheme for cheap or free milk for nursing mothers and young children. It was widely praised and, while the evacuation of Dunkirk was taking place, was accepted by the House of Commons without opposition or even debate. Some thirty or so years later, Margaret Thatcher first came to real national prominence (and many thought the possible end of her political career) when, as Education minister, she introduced the beginning of the end of the scheme. Young children, most of whom were perhaps more enamoured with the rhyme rather than any future lack of morning milk that seemed to be either served warm or frozen solid, chanted in the playground, ‘Mrs Thatcher, Mrs Thatcher, Milk Snatcher.’

When the Blitz hit the East End of London, Boothby was encouraged by Woolton to visit the air-raid shelters as they were emptying at six in the morning when the all-clear siren sounded. Boothby quickly organised canteens all over the East End, run by volunteers, to provide free cups of tea. One day Boothby came across a small boy crying. When he asked him the matter the boy said: ‘They burnt my mother yesterday.’ Thinking the boy was referring to an air raid, Boothby said: ‘Was she badly burned?’ The boy looked up and said through his tears: ‘Oh yes. They don’t fuck about in crematoriums.’

Later on that summer the Daily Mirror reported that a new ‘fortified’ bread was to revolutionise and increase nutrition with added ‘energy-producing’ Vitamin B1 and calcium. ‘This is an unprecedented and a revolutionary step,’ announced Boothby, ‘and along with the milk scheme will be hailed by scientists all over the world as a great advance on anything hitherto achieved in this field.’ Boothby’s passionate evangelising about healthy bread, however, was not completely to do with the population’s good health.

It soon came to light that the Welwyn Garden City company Roche was supplying the synthetic vitamin B1 in vast and highly profitable quantities. Boothby had once been the chairman of directors of Roche but had stood down when he was given his recent governmental role. As a parting gift from the company, however, he had been given 5,000 shares. When Woolton found out about this Boothby was forced to sell them which made him a lot of money in the process. Woolton was shocked that Boothby was allowed to keep the share-selling profits.

Boothby was starting to get a bad reputation at Westminster, and his addiction to gambling and its associated debts meant that he was always looking for more money. His business activities in the arms trade brought him into contact with Richard Weininger (a suspected German agent who was arrested at Boothby’s flat before being interned by the British government). Boothby was indebted to the Austrian-Czech émigré and stood to receive a commission if, by using his influence in government, Weininger benefitted from the release of his Czech assets impounded by wartime regulations. After asking questions in the House about the matter in October 1940, Boothby was suddenly suspended from duties when it was found that he had failed to declare his interest. Boothby had no alternative but to resign. In his autobiography he wrote of the matter: ‘The single sentence “I have an interest to declare” would, it seems, have cleared me. I can only say that it never occurred to me to say it.’ Churchill’s advice to his former Parliamentary Secretary when he came to him asking what he should now do after his resignation, was, ‘Get yourself a job with a bomb disposal unit.’

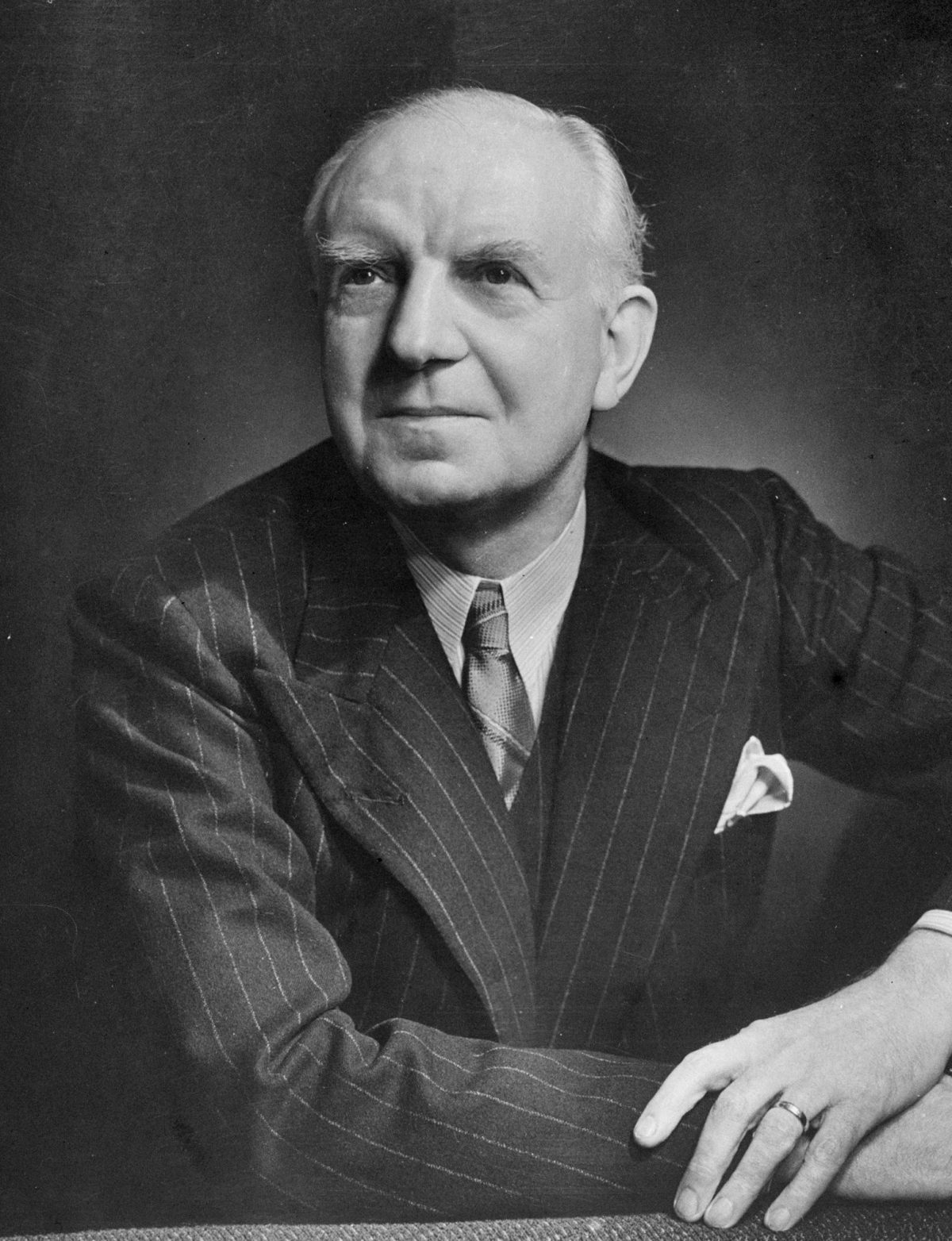

Lord Boothby 1958

After thirty-five years as an MP, nearly all of them as a backbencher, in 1958 he was made a peer by the Conservative Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan. It was a benevolent act – the first (and last) Baron Boothby of Buchan and Rattray Head had been having an affair with Macmillan’s wife Dorothy since around the beginning of 1930. For the first five years they virtually lived together, almost openly. Sarah, Dorothy’s third child, was Boothby’s although treated by Macmillan as his own. Ludovic Kennedy once asked Boothby what he saw in her, to which he replied, ‘Dorothy has thighs like hams and hands like a stevedore, but I adore her.’ In 1935, Boothby attempted to extricate himself from this impossible relationship by proposing to one of Dorothy’s cousins, Diana Cavendish. The proposal, according to Boothby, came after rather too good a dinner. The next morning he realised he had made a huge drunken mistake, but before he had a chance to make amends Diana’s mother, to his horror, had already announced the news to the world, including a delighted Winston Churchill.

It was a doomed and brief marriage, and, as Boothby’s biographer subtly put it: ‘It was not long before Diana realised that her husband’s many qualities did not include those normally associated with a successful husband.’ Boothby felt guilty for the rest of his life and once said: ‘It is impossible to be happily married when you love someone else.’ In May 1937, after just two years of marriage, there was no choice but divorce – a decision not taken lightly in those days, especially for a Scottish MP. Boothby wrote to his friend Lord Beaverbrook, pleading: ‘Don’t let your boys hunt me down.’ The press baron had words with the relevant people and the divorce registered just a few lines in most newspapers, if anything. The affair, however, put an end to any hopes Boothby might have had of achieving high office.

Macmillan and Dorothy on the day they married in 1920.

Despite the long relationship with Lady Macmillan and his marriage to Diana, Boothby was bisexual. In his autobiography, published in 1978 (in which, incidentally, he mentions Dorothy not once), he hinted of past gay dalliances. Of his time at Oxford University he wrote: ‘As for the homosexual phase, most of the undergraduates got through it; but about 10 per cent didn’t. Homosexuality is not indigenous in Britain, as it is in Germany … but it is more prevalent than most people wish to believe.’ In the 1920s and 30s Boothby often visited Germany and wrote: ‘Among the youth, homosexuality was rampant; and, as I was very good-looking in my twenties, I was chased all over the place, and rather enjoyed it.’

On the same subject, Boothby also mentions a speech he made to the Hardwicke Society (a senior debating club for barristers) at Cambridge University in February 1954, in which he proposed that the clause that made ‘indecency between consenting male adults in private a crime should be removed from the Statute Book’. Boothby sent a copy of his speech to the Home Secretary and called for a royal commission, to which David Maxwell-Fyfe replied: ‘I am not going down in history as the man who made sodomy legal.’

There had long been rumours that Boothby was consorting with young men, but, as usual, the newspapers refused to report anything untoward in his private life. A few hints broke through, however. In 1959, the Daily Express reported, with the headline ‘THIEF “LETS DOWN” BOOTHBY’, that seventeen- year-old Robert Bevan, in the dock at Marlborough Street Magistrates’ Court, had been accused of stealing a gold watch and chain and a large gold coin, together worth £50. The court had been told that he phoned Lord Boothby to ask for help in finding a job, and as the lord’s manservant Goodfellow was away the young man was invited to help out in his flat in Eaton Square. Boothby was reported to have said: ‘He is very young – I think the temptation was too great.’

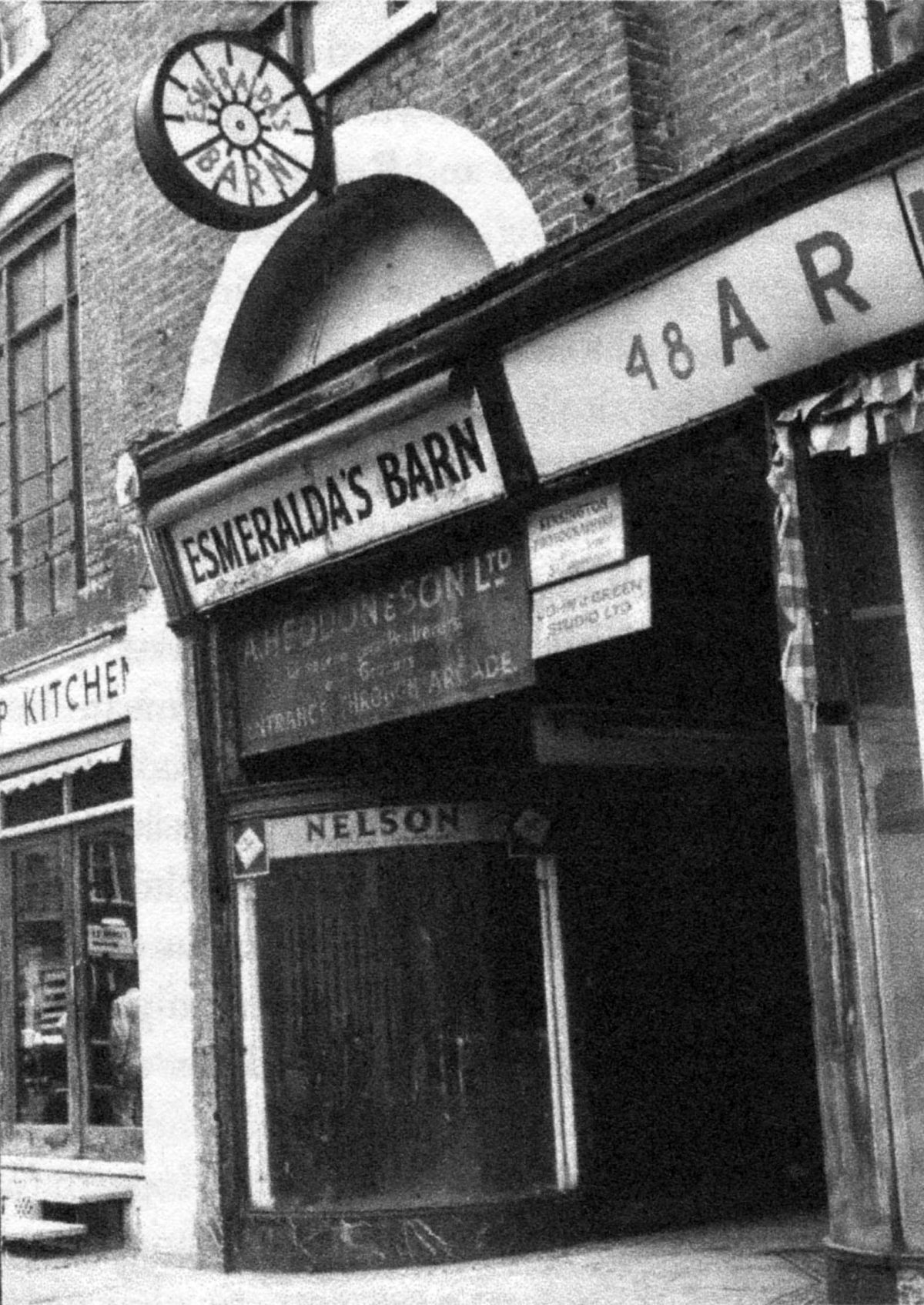

A few years later, in May 1963, a month or so before John Profumo admitted to having had an affair with Christine Keeler, the Daily Express reported about another seventeen-year-old boy who had been sent to borstal, this time for trying to cash a £1,899 cheque of Boothby’s at the peer’s bank. The boy said that he had found the chequebook on the King’s Road, and when told the chequebook was still at Lord Boothby’s flat he said, ‘I lied about that, but all the rest is true.’ The Express wrote: ‘The riddle: How the cheque came into the possession of Buckley, a cloakroom attendant at Esmeralda’s Barn, Belgravia.’

Esmeralda’s Barn in Knightsbridge

Esmeralda’s Barn, in the 1950s, was a relatively conventional nightclub run by a man called Stefan de Faye and situated in Wilton Place in Knightsbridge, where the Berkeley Hotel now stands. After the Betting and Gaming Act of 1960 gambling became legal in the United Kingdom, and from 1961 de Faye turned Esmeralda’s Barn into a gambling club. The Kray twins acquired Esmeralda’s and found it a lucrative venture. Regular visitors to the club included the artists Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon. David Somerset, Duke of Beaufort, said in the BBC documentary Lucian Freud: A Painted Life how Freud had once arrived at his home to ask for a £1,500 loan. When asked why he needed so much money at such short notice he replied, ‘Because if I haven’t produced it by twelve o’clock they’re going to cut my tongue out.’

If customers sometimes got carried away and accumulated large debts, that was not necessarily a bad thing for the Krays, as it put them in their power. At one point one of the twins’ associates, David Litvinoff, accumulated debts of £3,000. Ronnie Kray agreed to waive this debt in return for the lease on Litvinoff ’s flat at Ashburn Gardens in Kensington but also ‘access’ to Litvinoff’s lover, Bobby Buckley (brother of James ‘Jimmy’ Buckley, who was found with Boothby’s cheque), a croupier at Esmeralda’s Barn. Litvinoff, meanwhile, continued to live at Ashburn Gardens as part of the deal. Ronnie enjoyed being able to choose waiters and croupiers at Esmeralda’s Barn that suited his own preferences for attractive young men. According to the journalist and writer John Pearson, ‘the Barn’ became the centre of Ronnie’s own ‘private vice ring’ which included private sex shows at Ashburn Gardens but also, with Boothby and Tom Driberg in attendance, at the Krays’ flat at Cedra Court in Bethnal Green where, as Francis Wheen, Tom Driberg’s biographer put it, ‘rough but compliant East End lads were served like so many canapés’.

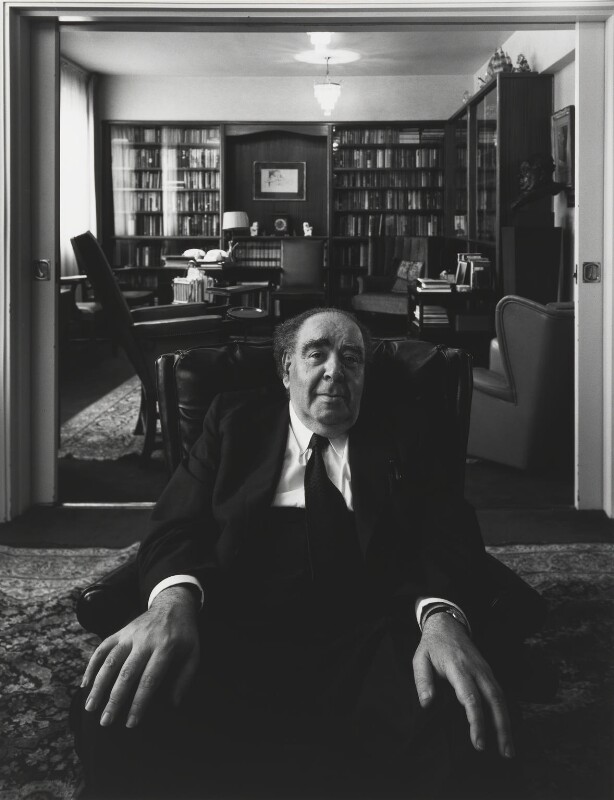

Thomas Edward Neil (‘Tom’) Driberg, Baron Bradwell

by Ronald Franks

chlorobromide print, 1966

After the Daily Mirror headline and the subsequent story in Stern that actually named him, Lord Boothby was in a tricky situation. If he decided to do nothing it would seem as if he was admitting the accusations; however, if he sued Mirror Newspapers he could be involved in a lengthy and expensive court case, with a real risk that all kinds of revelations would be raked over to support the story. At this stage senior members of the Tory party were terrified that the scandal was likely to rival the Profumo affair (which had also gently simmered under the surface for a while), and as there was a general election looming it was a situation the party could ill afford. Two Tory backbenchers had even reported to their chief whip, Martin Redmayne, that they had seen Lord Boothby and Tom Driberg importuning males at the White City dog track and that they were involved with gangs of thugs who laundered money at the tracks.

MI5 files, which were open to the public 2015, noted: “Boothby is a kinky fellow and likes to meet odd people and Ronnie [Kray] obviously wants to meet people of good social standing, he having the odd background he’s got and, of course, both are queers. The file also said that Boothby and Kray attended gay sex parties together, where they “hunted” young gay men who they referred to as “chickens”. At Chequers the story and its implications were debated by the Lord Chancellor, Lord Dilhorne, the Home Secretary, Henry Brooke, and the Prime Minister, none of them feeling that Boothby’s pleas of innocence were the least bit plausible.

Boothby’s connection with Tom Driberg, which was now coming to light, meant that the Labour Party were in no mood to take advantage of the situation. If Boothby went to court then it seemed more than likely that Driberg’s private life would also be exposed. Driberg’s connection to the Boothby scandal meant that Harold Wilson’s personal solicitor, the louche, overweight Arnold Goodman, became involved.

Arnold Abraham Goodman, Baron Goodman

by Arnold Newman

NPG, 1978

To Wilson, as well as many others, Goodman was known by the name ‘Mr Fixit’. Private Eye, however, preferred ‘Two Dinners’ Goodman’, or when mocking his sanctity, ‘Blessed’ Goodman. The satirical magazine would also regularly mention a firm of solicitors called ‘Goodman, Badman, Beggarman and Thief, solicitors and commissioners of Oaths’. Arnold Goodman offered to represent Lord Boothby and advised the troubled peer to write a letter to The Times admitting that it was him in the picture but denying all of the Mirror’s allegations:

I have never been to all-male parties in Mayfair. I have met the man alleged to be King of the Underworld (Ron Kray) only three times, on business matters, and then by appointment at my flat, at his request, and in the presence of other people. The police deny having made any report to Scotland Yard or the Home Secretary in connection with any matters that affect me. Lastly, I am not, and never have been, homosexual. In short, the Sunday Mirror allegations are a tissue of atrocious lies.

The letter ended: ‘If Mirror Newspapers possess any documentary or photographic evidence to the contrary, let them print it and take the consequences.’ After The Times published the letter, Goodman won a quick agreement from the International Printing Corporation, owners of the Sunday Mirror, saving Boothby from the court case he and the government were dreading. This wasn’t all: Goodman won his client a record out-of-court settlement of £40,000 (not an inconsiderable sum back then, and approximately £750,000 in 2017) and a grovelling and demeaning public apology signed by Cecil King, the chairman of IPC. Boothby would later say that he had given away the £40,000. Because he had essentially perjured himself in public, the peer was extremely vulnerable to anyone who could prove he had lied. Thus much, if not all, the money went to Ronald Kray.

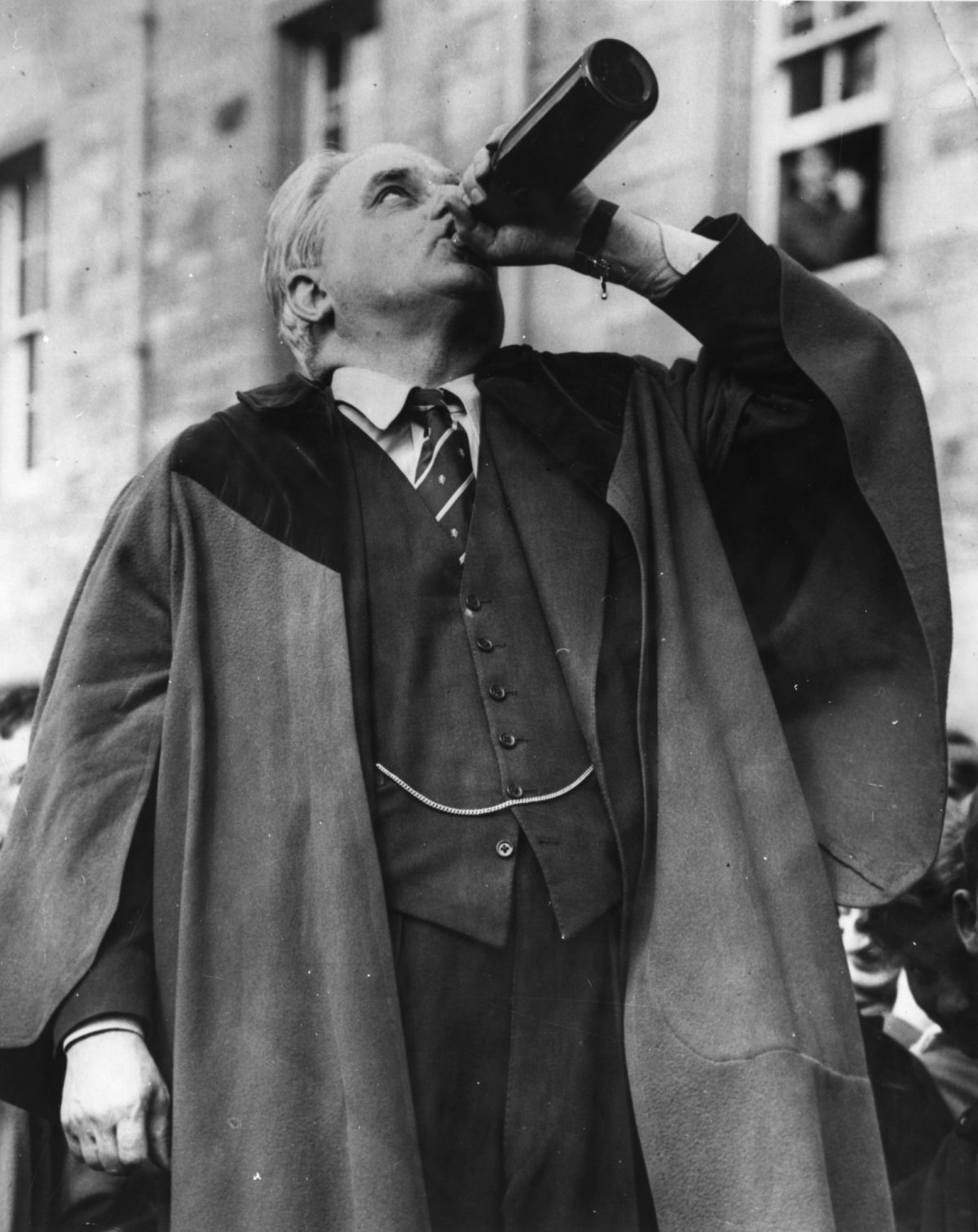

Robert Boothby downs bottle of ale at the traditional ceremony when he was made Rector of Aberdeen University

Bob Boothby and Ronnie Kray at the Society restaurant

Derek Jameson, the Daily Mirror picture editor, and future editor of the Daily Express and News of the World, once recalled that for a long time Fleet Street refused to go anywhere near the Krays: ‘Dodgy trouble, £40,000, not very nice,’ he said. Subsequently, for years the Twins were known by the Mirror and other publications as ‘those well-known sporting brothers’. The Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Sir Joseph Simpson, also had to deny publicly that there had ever been a police investigation of the Boothby–Kray affair. Since the beginning of 1964, however, the Kray twins and their gang had been under the scrutiny of Detective Chief Inspector Leonard Read, also known by his nickname ‘Nipper’.

On 10 January 1965, the Kray twins were arrested and charged with demanding money with menaces from Hew McCowan, owner of a club in the West End called the Hideaway. They were refused bail and sent to court. It was hard enough for Read to find anyone sufficiently suicidal to testify against the Krays, but the case against them wasn’t helped when, a month after their arrest, Boothby stood up in the Lords and inquired, shamelessly, whether the government intended to keep the Kray twins in custody for an indefinite period. He added: ‘I might say that I hold no brief for the Kray Brothers.’ No one believed him, and unsurprisingly there was complete uproar in the house after the question, to which Boothby shouted, ‘We might as well pack up.’

At the end of the trial the jury failed to reach an agreement and a re-trial was ordered; the judge eventually stopped the second trial, finding for the defendants. Fleet Street and the Metropolitan police felt that the Krays now had a complete hold over the Establishment, and their control over London’s underworld would remain unchecked for four more years.

A police photograph showing blood stains on the floor inside the Blind Beggar public house in Whitechapel where George Cornell was killed. Ronald Kray and John Barrie were convicted of the murder and sentanced to life. * and Reginald Kray was convicted of accessory after the fact and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment. The photo is one of many documents and files that have become public, at the Public Records Office in Kew in south west London.

The Krays were arrested again in 1969 for the murders of George Cornell and Jack ‘The Hat’ McVitie. At the same time sixteen of their firm were also arrested, which helped witnesses to come forward without fear of intimidation. Ronnie and Reggie were eventually sentenced to life imprisonment with a non-parole period of thirty years for the murders of Cornell and McVitie, at that time the longest sentences for murder ever passed at the Central Criminal Court.

Boothby and Kray and ‘Mad’ Teddy Smith at Boothby’s Eaton Square apartment

Sunday Times Magazine, 1 April 1973

There was, of course, a third man in the famous photograph taken at Lord Boothby’s flat – Leslie Holt, Ronnie’s sometime driver and lover, who was also used as bait to entrap the likes of Robert Boothby and Tom Driberg. Holt eventually became the partner of a Dr Kells, based in Harley Street, and it was said that the society doctor would supply customers for Holt’s cat burglaries. It was a lucrative project that worked well until police became suspicious of the criminal double act. Holt mysteriously died at the hands of Kells when he was under anaesthetic for a foot injury. The doctor was arrested but eventually acquitted.

Lord Boothby was married for the second time in 1967, to a Sardinian woman called Wanda Sanna, thirty-three years his junior. ‘Don’t you think I’m a lucky boy!’ he shouted out to well-wishers outside the ceremony at Caxton Hall around the corner from his flat.

Boothby’s marriage to Wanda Sanna at Caxton Hall in 1967

William Deedes, former Conservative MP and editor of the Daily Telegraph, once wrote of his friend as someone who ‘simply could not resist drinking from brim to dregs every cup offered him’. Sadly at the end of Boothby’s life the cups consisted of nothing but whisky and Complan. Boothby once told Ludovic Kennedy that euthanasia should be compulsory at the age of eighty-five. He was never very good at taking advice, even his own, and Lord Boothby died in Westminster in 1986, aged eighty-six.

This post is an excerpt from the acclaimed High Buildings, Low Morals by Rob Baker.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.