“I think a future flight should include a poet, a priest and a philosopher . . we might get a much better idea of what we saw.”

– Astronaut Michael Collins

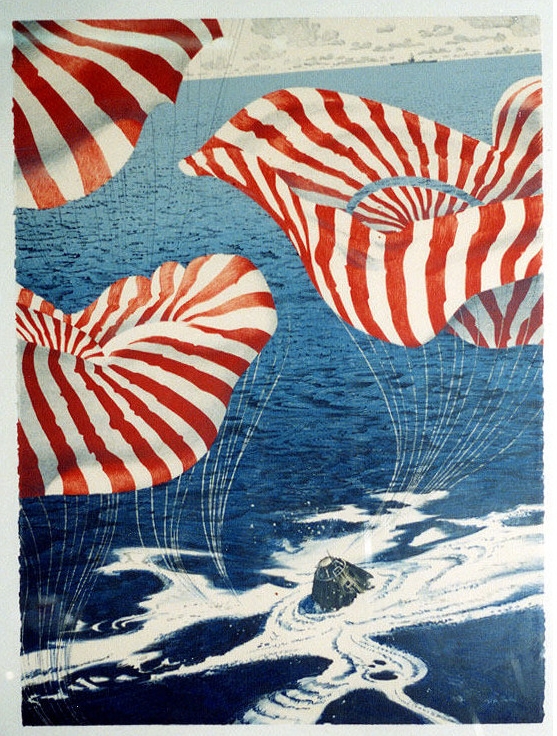

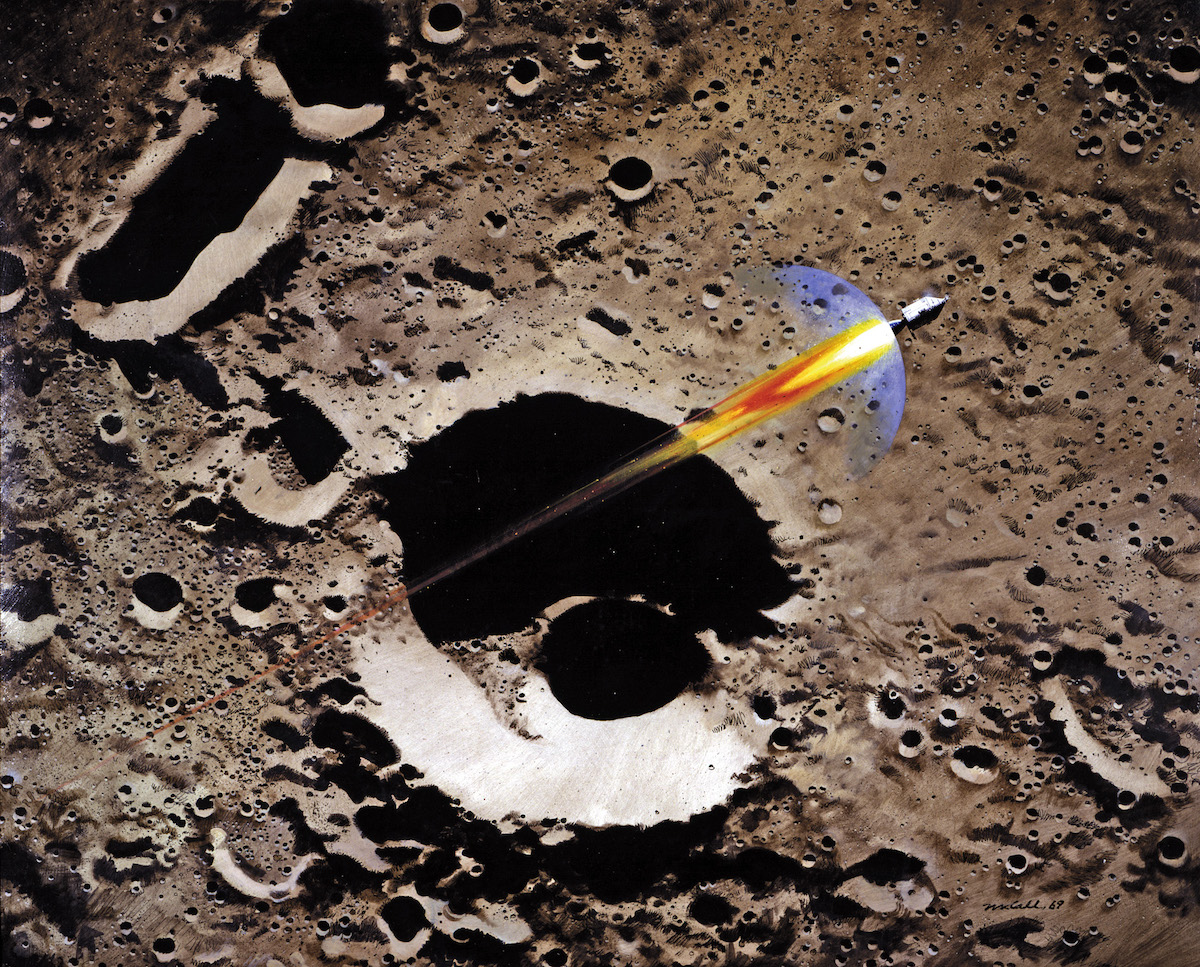

Apollo 8 Coming Home y Robert McCall – ‘Apollo 8 Coming Home’ by Robert T. McCall, 1969

Human eyes directly observed the far side of the Moon for the first time on Christmas Eve 1968. Robert McCall imagines the sight of the rocket engine firing to propel the spacecraft out of lunar orbit for its return to Earth.

The Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum is home to a vast array of artwork. In 1962, four years after the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was created as a federal agency, James Webb established NASA’s Artist’s Cooperation Program.

Influenced by the U.S. Air Force’s art program, Webb wanted art to communicate the cultural significance of the space program way from the noise of politics and TV. Space exploration was for all human kind. If the astronauts get there, then we all get there. Because up there is the wonder of possibility.

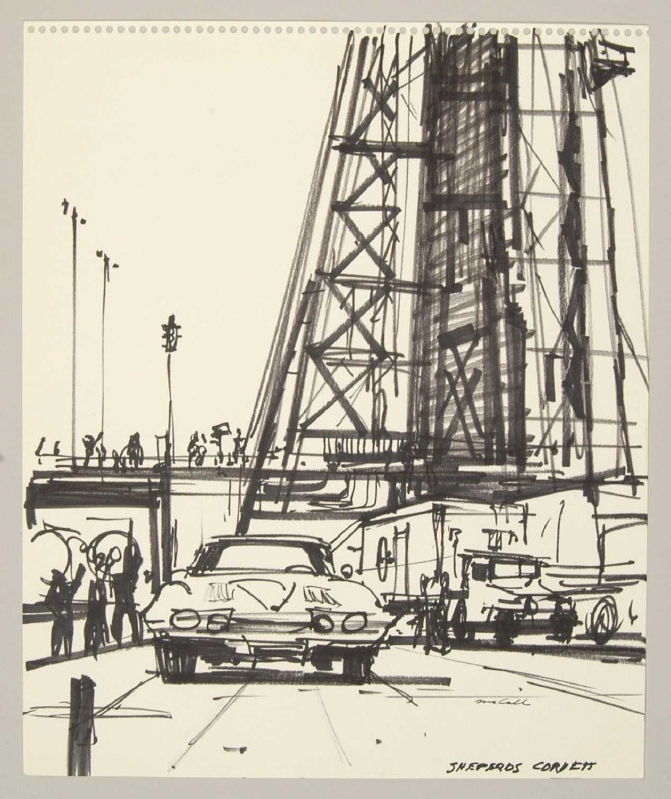

Predawn, 1963 by Peter Hurd

Peter Hurd was one of the first eight artists invited to join the NASA Art Program. The artists were given access to the space programme which rolled out with the last flight of the Mercury Program. Predawn depicts the launch site shortly before Gordon Cooper’s sub-orbital Mercury Atlas (MA-9) flight in May 1963.

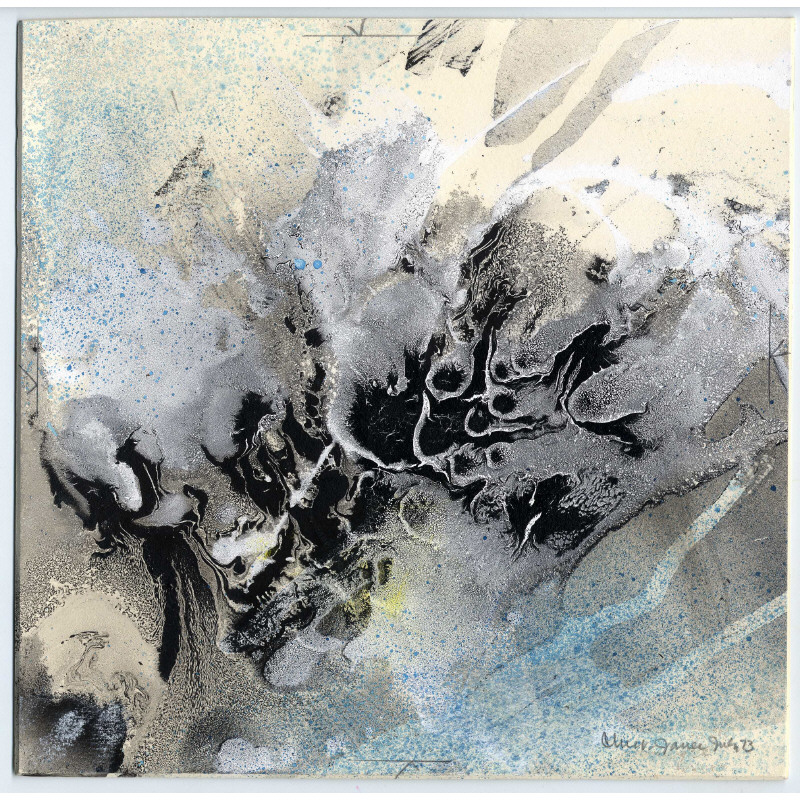

Lamar Dodd, Max Q, 1963

James Dean was the founding director of the NASA Art Program who coordinated artists’ visits. A trained artist himself, Dean shared an story about when Peter Hurd and Lamar Dodd (1909 – 1996), hoped to work in a field at night to paint the gantry lit under huge spot lights.

“So I got two huge lamps and they took them and went off into the field and began working. And nobody on the launch pad knew what they were doing there. But [security] saw these lights out there in the bushes, and they were concerned…

“So [the security] got in the car and drove out to find out what was going on. And they walked through the little scrubby bushes and they found these two old guys sitting on the ground with little brushes, paint, and some water, doing these paintings. It turned out that a security guard from Georgia recognized Dodd’s Georgia southern accent, and after a friendly conversation, they were invited to the top of the launch pad where they were also allowed to view the interior of the empty space capsule that awaited astronaut Gordon Cooper. While Hurd’s final Predawn painting focused on the initial view of the gantry painted in the field by lantern light, Dodd based his interior of the space capsule for a painting titled Max Q from this experience.”

Many of us have looked up and been inspired to dream and create. Cosmonaut Alexei Leonoz survived a trip to the great beyond and lived to paint the tale. In the 16th Century German artists produced The Comet Book (‘Kometenbuch’) of Stylised Comets and Meteors, in 1750 Thomas Wright gave us An Original Theory or New Hypothesis of the Universe; in 1879 Richard A. Proctor drew Flowers of the Sky; in the early 20th Century people too snapshots Live From The Moon; and Étienne Léopold Trouvelot showed us the heavens. And science fiction writers had a field day. And do you fancy living in a NASA space colony?

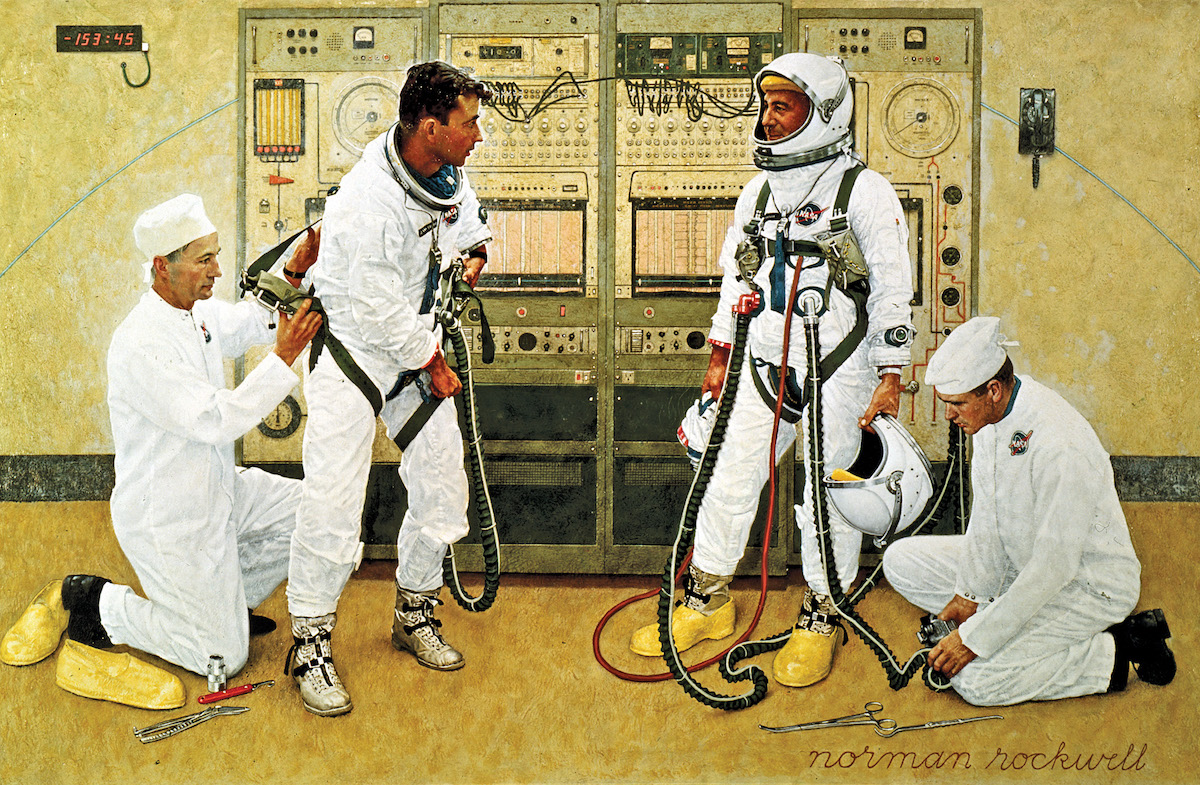

Grissom and Young by Norman Rockwell – Astronauts John Young and Gus Grissom are suited for the first flight of the Gemini program in March 1965. NASA loaned Norman Rockwell a Gemini spacesuit in order to make this painting as accurate as possible.

“Space travel started in the imagination of the artist, and it is reasonable that artists should continue to be the witnesses and recorders of our efforts in the field.”

– Hereward Lester Cooke (1916 – 1973), Curator of Painting, National Gallery of Art.

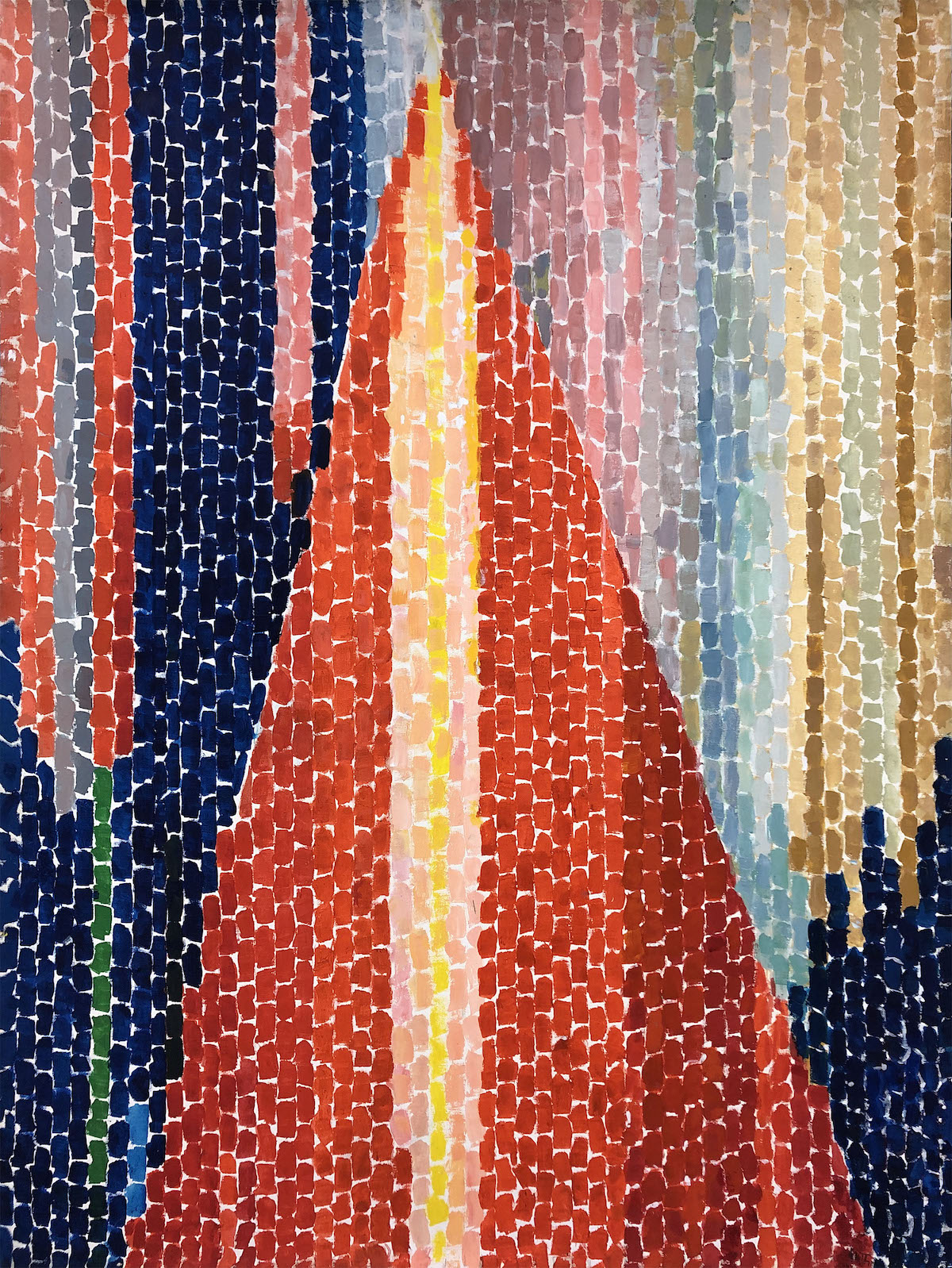

Blast off! by Alma Woodsey

Gemini Launchpad by James Wyeth, 1964

“When once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return.”

– Leonardo da Vinci

Saturn Blockhouse by Fred Freeman, 1968

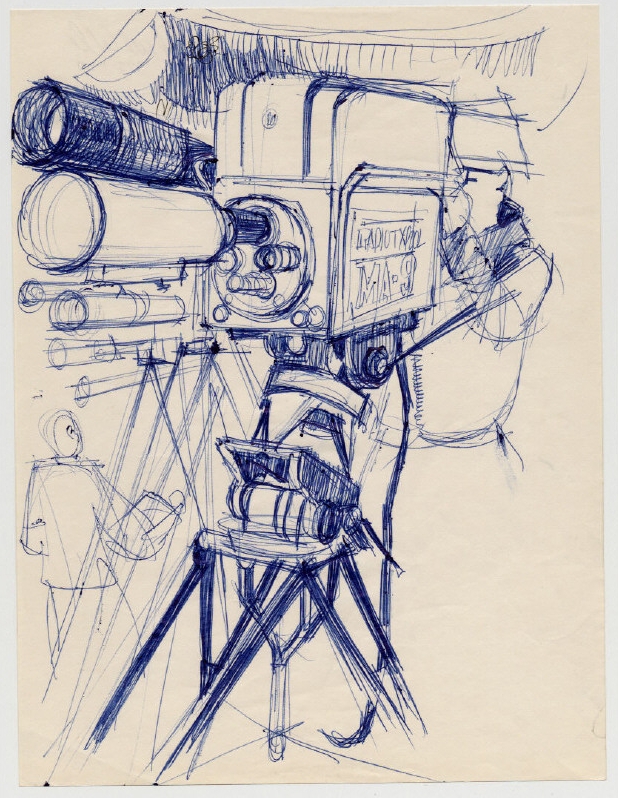

TV Camera and Cameraman (ball point pen on paper) 1963 by Paul Calle

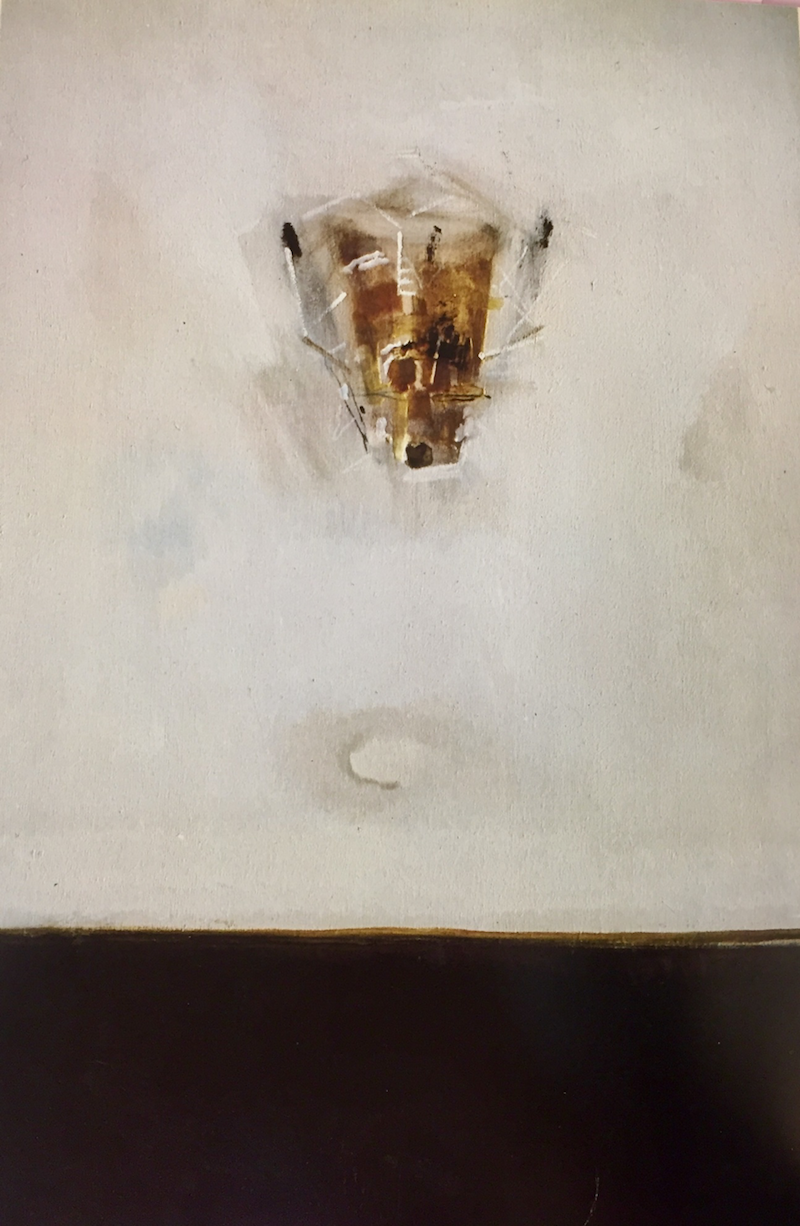

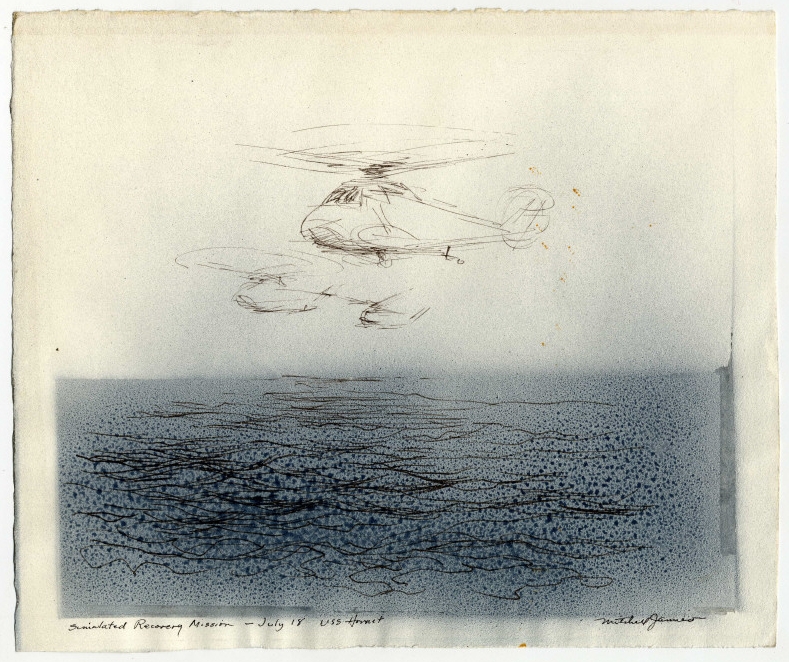

Heli Pilot Sighting CM (charcoal + ink on paper) 1969 by Mitchell Jamieson

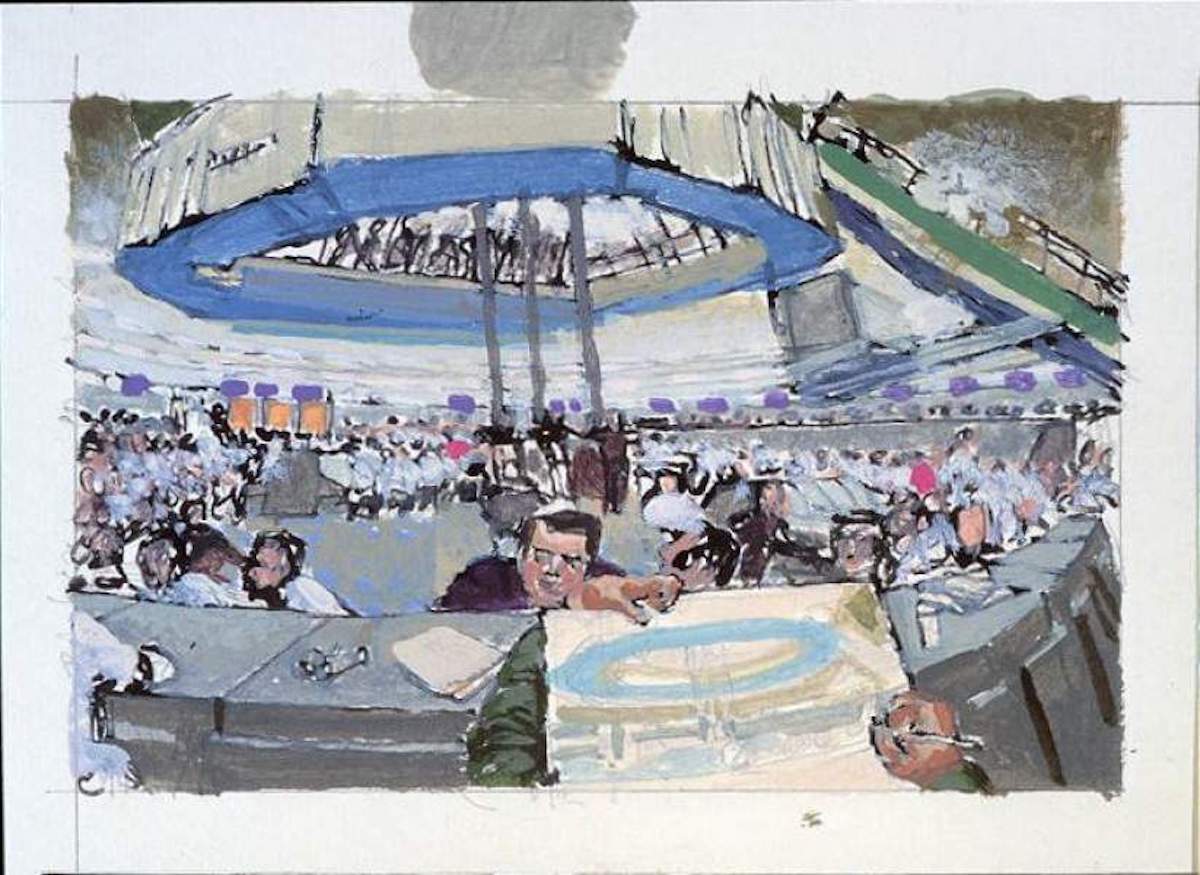

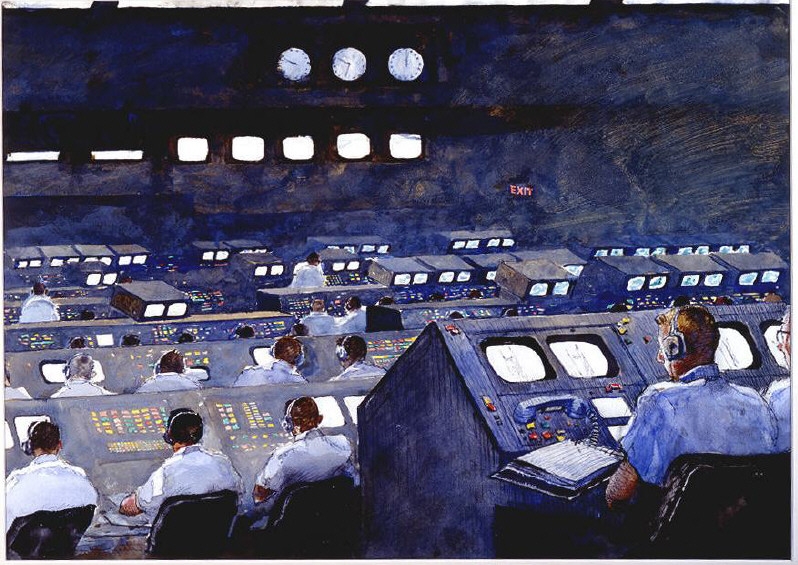

Firing Room (acrylic painting on paper) n.d. by James Wyeth

“A view from the back of the firing room, which is headquarters for Launch Control at the Kennedy Space Center. Rows of consoles and people seated facing them extend from the foreground to the middleground, occupying half of the space. Five light blue monitors are on the wall above the consoles, and three clocks are above them. An illuminated exit sign is in the empty dark space on the right.”

Unfinished Monster (watercolour on paper) 1964 by Hugh Laidman

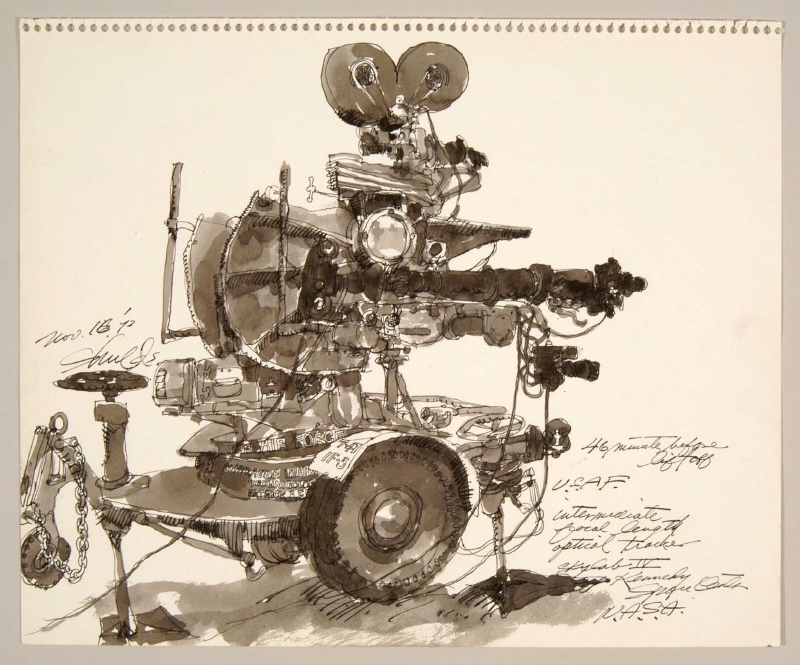

Intermediate Focal Length (pen,ink + ink wash on paper) 1973 by William Shields

Simulated Recovery Mission (pen, ink + airbrushed ink on paper) 1969 by Mitchell Jamieson

‘Sky Garden’ by Robert Rauschenberg, 1969 (lithograph on canvas)

In 1969 Rauschenberg was invited to witness one of the most significant social events of the decade: the launch of Apollo 11, the shuttle that would place man on the moon. NASA provided Rauschenberg with detailed scientific maps, charts and photographs of the launch, which formed the basis of the Stoned moon series – comprising thirty-three lithographs printed at Gemini GEL. The Stoned moon series is a celebration of man’s peaceful exploration of space as a ‘responsive, responsible collaboration between man and technology.’ The combination of art and science is something that Rauschenberg continued to investigate throughout the 1960s in what he calls his ‘blowing fuses period.’

Via: NASA’s Eyewitness to Space Collection. And Smithsonian.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.